A colossal monument sits at the crest of a hill. Its architecture reimagined what came before, but its success would inspire countless imitations. The monument became famous around the world. Years later, it still stands today.

I am talking, of course, about 7 Wonders.

7 Wonders is a card drafting game designed by Antoine Bauza in 2010. Known for its broad player count and short runtime, 7 Wonders was honoured by the Spiel des Jahres Jury with an Expert Game of the Year award (Kennerspiel des Jahres) in 2011. In our long-form article examining the most important games of the 2010s, 7 Wonders came in (fittingly) at #7. So what made the game so special?

Before we can get into that, let’s take a look at how it plays.

The Rules

The premise of 7 Wonders is simple: each player represents a different ancient civilization working to build the framework that will advance their society. Among these structures are institutes of learning, centers of trade, and of course their Wonder: a civilization-specific monument that gives each player an overarching goal to work towards. The game lasts for three Ages and then everyone tallies their points. The person with the most points wins.

In 7 Wonders, turns are taken simultaneously. Each player has a hand of cards; as your turn, you have to choose one of them to play. Once everyone has chosen, you pass your hand of cards to your neighbour. Then, the next turn begins. This system of choose-and-pass is known as card drafting and it’s become a popular mechanism in the years since 7 Wonders’ release.

Once a card has been chosen, the player must use it for one of three things:

- Play the card. This is the default option. Each card has some kind of benefit. When you play the card, it enters your tableau*. There’s often a cost associated with playing the card; more on that in a second.

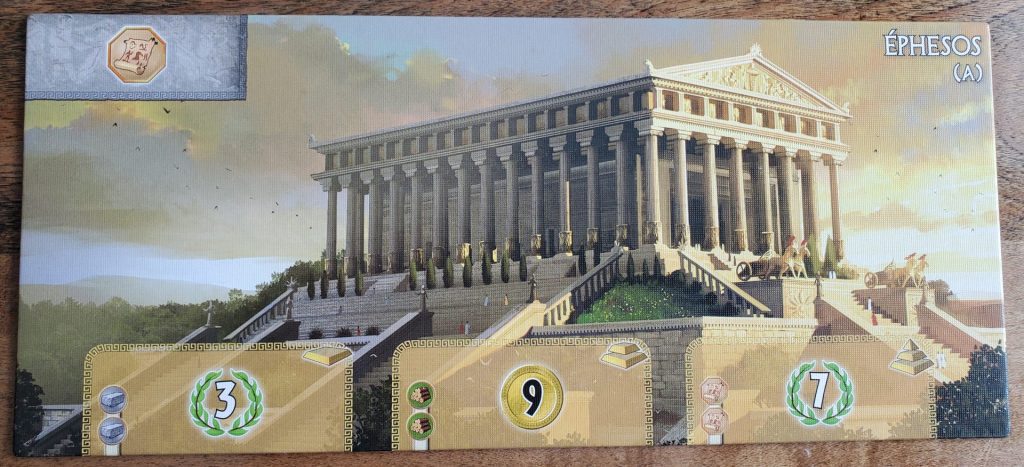

- Discard the card to build a piece of your Wonder. Each player has a unique Wonder that gains them a special benefit when built. Wonders usually take three cards to complete, but each card you contribute will gain you a reward. Any costs or benefits from the card you’re using are ignored, replaced by the Wonder’s own stated cost and reward. The only reason the card itself matters is because it’s removed from circulation.

- Discard the card to get three coins, which are used to play cards.

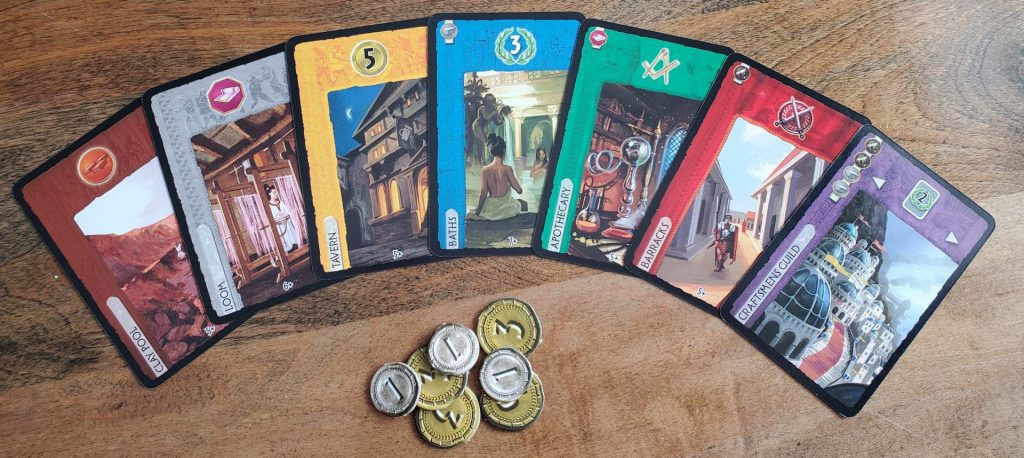

So what happens when you play a card? Well, first off, you have to pay for it. Cards have icons in the top left corner showing coins or a mix of resources. This is the card’s cost.

7 Wonders uses a clever system to track resources: there are no resource tokens in this game. Instead, resources are granted by cards previously played into your tableau. The printed resource value gives you one permanent unit of that resource, which you can spend once per turn.

No resource? No problem! You can buy access to your neighbouring players’ tableau of resources, but it’ll cost you two dollars apiece. To keep the game quick, there’s no negotiation involved; my use of your stone doesn’t prevent you or another neighbour from using it that turn.

Cards offer a wide variety of benefits, all coded based on their colour. Here’s a rapid-fire overview:

- Brown and grey cards (Raw and Manufactured Goods) give resources.

- Yellow cards (Commercial Structures) are varied, but usually give you coins or reduce other costs.

- Blue cards (Civilian Structures) are worth points at the end of the game.

- Green cards (Scientific Structures) are worth end-of-game points, but they’re also a set collection mini-game. There are three different symbols on these cards and players are awarded points both for collecting matching symbols and for each set of three different ones.

- Red cards (Military Structures) offer another mini-game. At the end of each Age, everyone compares how many military icons are showing on their red cards. If you have more than your neighbour, you gain points and they lose a point.

- Purple cards (Guilds) only appear near the end of the game, and each will award players points differently based on other cards in their tableaus.

At the end of the game, your points are determined by whatever is printed on the cards in your tableau. The only other points come from your Wonder (if it grants you points), the military mini-games, and any leftover change you have kicking around. The whole game rarely takes more than half an hour once people know the rules — but there is a learning curve.

Icons & Approachability

7 Wonders can be a fast, fun experience. The decisions you make feel important, but there are few enough paths forward that you can make your choices fairly quickly. The last two games I played of 7 Wonders took no more than twenty minutes, with six players each.

And yet…

Once upon a time, I was a board game teacher in a little game café called Monopolatte. We would give people game recommendations, help them find what they needed, and teach them how to play. When I started working at Monopolatte in 2013, 7 Wonders was still a pretty hot, new game. What I’m saying is this: I’ve played 7 Wonders dozens of times. I’ve taught 7 Wonders hundreds of times. And there is always, always one big stumbling block for new players — the icons.

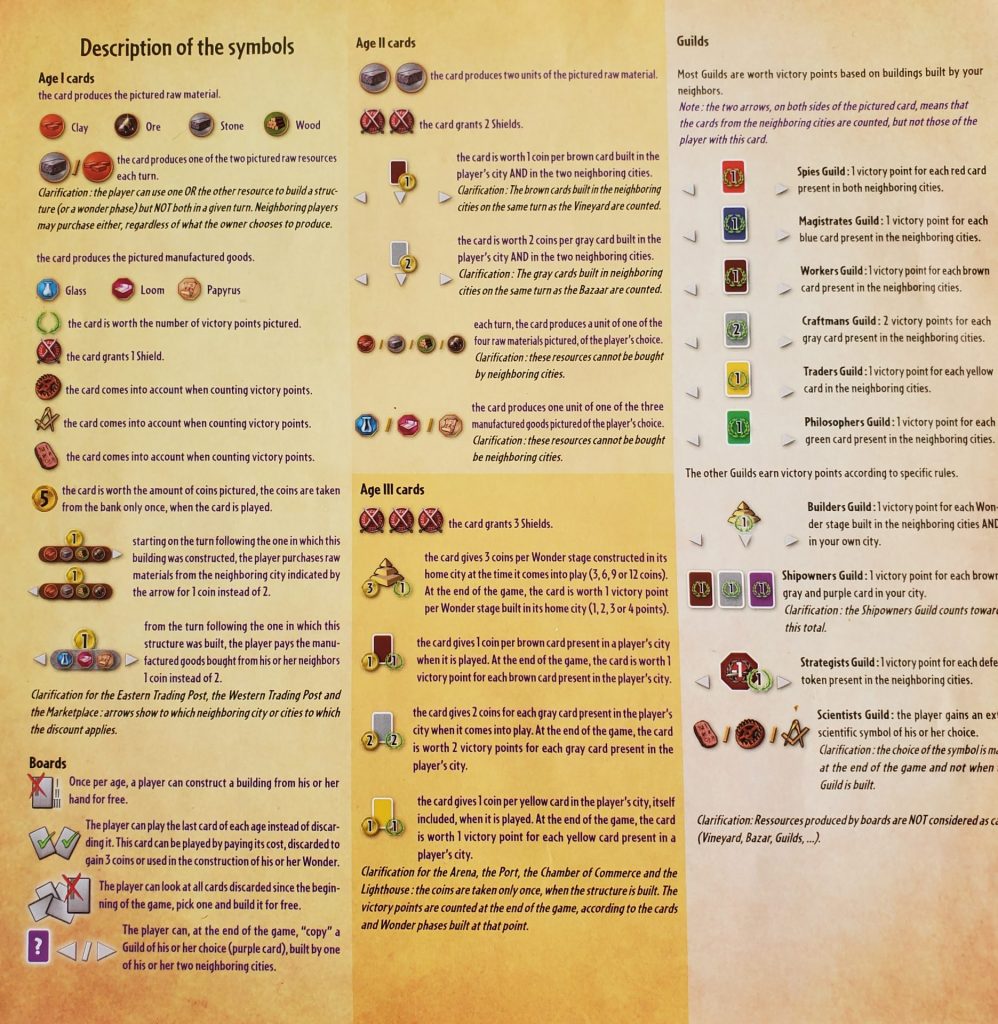

Every card in 7 Wonders has at least one icon on it. There’s an icon for each resource. There’s an icon for each type of science card. There are icons for trading, icons for fighting, icons for special powers. There are icons that only appear on a single card, or a single Wonder.

If it’s your first game of 7 Wonders, there will be at least a few times over the course of the game that you need to look at the symbol reference. Unfortunately, there’s only one reference and it’s the rulebook itself. If you’re playing with a group of seven people and none of you have played before, it’s going to be a painful first game of passing the rulebook and waiting your turn to look.

With that caveat aside, I do want to be clear — I think the icons are great. Once you know them, it’s a breeze to quickly glance at the card and see exactly what it does. The iconography is pretty consistent and everything goes faster than if the game had chosen to write a laborious paragraph at the bottom of every card. The game is also (almost) perfectly language accessible: you could be playing the game with six people who shared no common language and still know exactly what’s going on. The one exception here is that the name of a card will sometimes matter.

Happily, the September 2020 edition of 7 Wonders will have three small reference sheets included in the box. This was my biggest gripe about the original game, so I’m very pleased to see this change being made. The new version also replaces the name functions with yet more icons, so you really could play it with someone unfamiliar with the Roman alphabet.

The Past & The Present of 7 Wonders

When 7 Wonders was originally released, simultaneous card drafting was still a somewhat novel idea. Cards were drafted as a means to an end, but it was strange for the draft to make up the whole game. As a result, 7 Wonders found a lot of early comparisons to Magic: The Gathering’s card draft. Its closest contemporary was probably Fairy Tale, a draft-centric game originally released by a small Japanese publisher in 2004. Given the designer’s thing for Japan, I would be surprised if Fairy Tale didn’t serve as an inspiration for 7 Wonders on some level.

Regardless of what came before, it was 7 Wonders that would blow up. Its publisher Repos Productions claims that 7 Wonders has won more awards than any other game in board game history and I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that’s true. Since its release, 7 Wonders has sold over a million copies, and has produced six expansions and a standalone two-player spinoff. The game helped to popularize the simultaneous card draft: three years after its release, the hit game Sushi Go! would find its own success.

7 Wonders was an important milestone for its designer Antoine Bauza, who would go on to become one of the most prominent designers of the decade. In 2010 alone, Bauza released Hanabi, Mystery Express, and 7 Wonders; 2011 would see the release of yet another hit, Takenoko. The impact of 7 Wonders was huge, both for its designer and the broader board game world.

Okay, But Is It Good?

Yeah! It is!

But it’s not a perfect game, so let’s talk roses and thorns.

Strengths

- It’s fast. The list of seven player games that you can enjoy in half an hour is pretty short, especially if you want to avoid party games.

- The decisions feel important. Even though there’s a good dose of luck in what cards you see and when you see them, each choice feels like something that matters.

- It’s asymmetric. The game’s use of special powers (via the Wonders) can change what cards are “good cards” for any given playthrough.

- It’s pretty. The game’s illustrations are nice to look at, even if you end up staring more at the icons than the pictures.

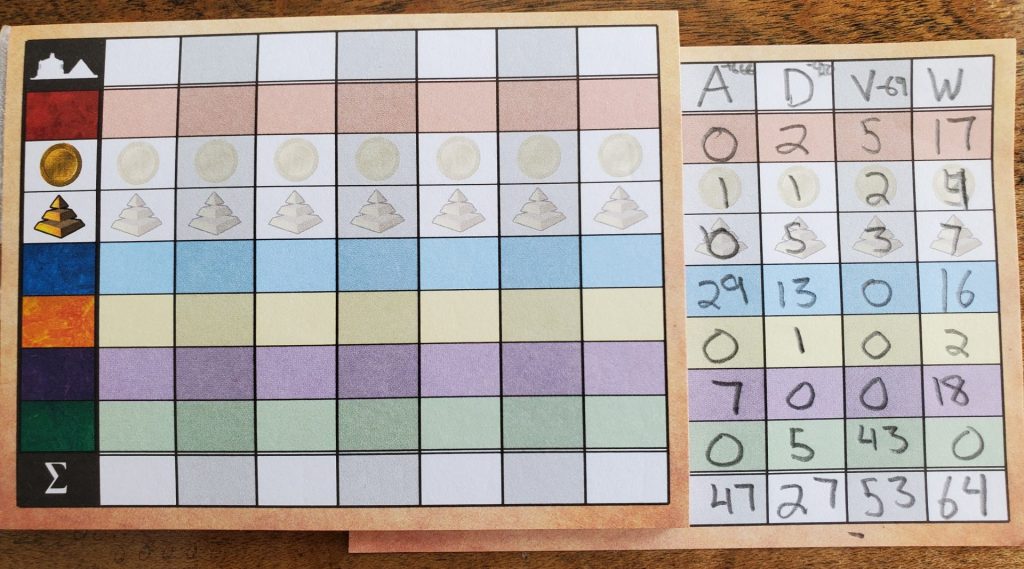

- The scoresheet is fantastic. It’s a clean and easy way to add everything up at the end.

Weaknesses

- Setup isn’t fun and it gets worse with expansions. You have to separate out cards based on player count to make the hands even. If you have one or more expansions, separating them out is pretty bad, too — at the board game café, we eventually stashed the expansions in the attic because it was such a hassle to reset.

- There aren’t references for the icons, though this is fixed in the September 2020 edition.

- The two-player game uses a dummy player. Some people actually love the two-player adaptation, but it’s a very different experience than the game at other player counts. I’m not a big fan. (Note that I’m not talking about 7 Wonders Duel, which is an entirely separate game.)

- It’s a pretty solitary experience. Yeah, you’re going to interact with your neighbours through your military and your resource purchases, but you’re in your own bubble a lot of the time. I don’t mind this, but people looking for interaction may be disappointed.

To sum it up: 7 Wonders is not only a good game, it’s also an important game. It launched a career, inspired hundreds of other titles, and still manages to feel fun and engaging ten years after its release. So what are you waiting for? Go out there and build something Wonderful.

Add Comment