When the World Health Organization first characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic, the virus had yet to really reach my neck of the world (Canada) and trying to grasp the severity of something that felt so abstract and unfamiliar wasn’t easy.

That was until I thought of COVID-19 as a virus in the game Pandemic. I pictured an area of the world covered in cubes of a single colour and then I imagined that as the game (or in real life, time) progressed, that disease began to spread until there was an outbreak and the coloured cubes that remained in their matching region started spreading to other differently coloured areas. Suddenly it all made sense.

But this article isn’t about the COVID-19 pandemic, it’s about a board game that I love: Pandemic.

Pandemic – Back When It Was Simply a Game

Pandemic is a cooperative board game for two to four players in which four deadly diseases are spreading around the world and it is up to the players to discover cures for each disease and save humanity.

Pandemic, designed by Matt Leacock, was first published in 2008 by Z-Man Games, but it was much earlier — in 2004 — when Leacock began designing this cooperative game shortly after the SARS epidemic. (In an open letter to the New York Times, he describes how he “imagined viruses would be the perfect antagonists for players to confront.”)

Fun fact: 5% of Matt Leacock’s design royalties for Pandemic games is donated to Médecins sans frontières (Doctors Without Borders).

At the time of its release, Pandemic was pretty groundbreaking. While it wasn’t the first cooperative game to exist — for example Ghost Stories and Space Alert were also published the same year — there were still very few cooperative games and even fewer that could be considered gateway games with streamlined mechanisms and a short playtime (right, Arkham Horror?). With the perfect amount of abstractness and a universally relatable theme, Pandemic was incredibly approachable.

Pandemic was also a huge success for North America. In an industry that was (and arguably still is) largely dominated by Europe — specifically German designers and publishers — Pandemic emerged as a hit for Matt Leacock and Z-Man Games, both American.

Pandemic was so successful, in fact, that not only did it become the go-to gateway cooperative game, but it also set a standard for how cooperative games operate — which then led Matt Leacock to rework Pandemic’s mechanisms for his Forbidden series of games (Forbidden Island, Forbidden Desert, and Forbidden Sky).

Once Pandemic finally reached Germany, it was nominated for the coveted Spiel des Jahres award in 2009 — and it probably would have won the award had it not been up against Dominion, another industry-changing game. More recently, Asmodee bestowed the title of “modern classic” upon Pandemic, along with five other quintessential gateway games: Dixit, Catan, Ticket to Ride: Europe, Splendor, and Carcassonne.

Fun fact: Of these modern classics, Pandemic is ranked the highest on BoardGameGeek’s rating system.

Now that you have some background on it, let’s take a more detailed look at how a game of Pandemic is played.

Pandemic’s Gameplay

As I mentioned, Pandemic is a game for two to four players — although you can play it solo if you want to control more than one role. In the game players are working cooperatively to suppress four diseases — blue, yellow, red, and black — while also working on finding a cure for each. There are a number of ways players can lose the game (which I’ll get into shortly), but there is only one way to win: discover cures for each disease.

Each player will have their own role to play in saving the world from infection; these roles feature special, rule-breaking abilities unique to them. While I do have my favourite roles (Medic, Quarantine Specialist, Scientist, and Operations Expert), I have forced myself to play with other roles at the various player counts and I can say that the roles feel balanced and are all equally helpful. That said, in my opinion, you always want to have at least one person playing a role that directly affects the diseases like the Scientist, Medic, or Quarantine Specialist.

The Player Cards

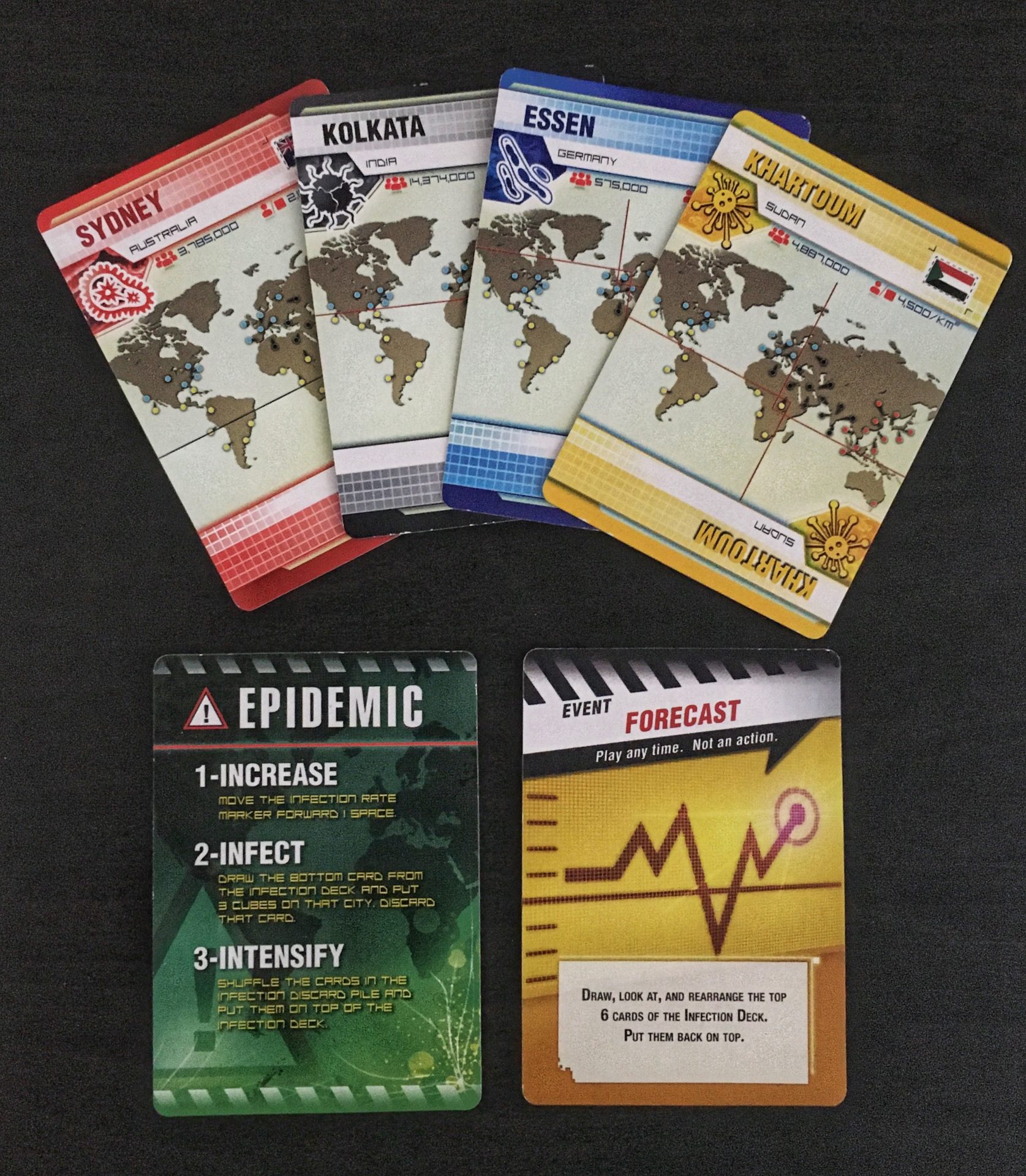

Players also start the game with a hand of Player cards and each turn you’ll draw two more cards from the Player deck. The majority of the cards in this deck are City cards, but there are also Event cards and Epidemic cards.

The colour of the City cards match one of the four diseases and correspond to the region of the world that disease infects. City cards are helpful for a few reasons, most notably one player needs to collect five City cards of a single disease colour to discover a cure for that disease.

Event cards are the best and, when played at the right moment, could win you the game. There are five unique Event cards that can be played without spending an action by any player and (typically) at any time.

Epidemic cards are the worst and they pose the biggest challenge for players. At the beginning of the game, players decide how many Epidemic cards are added to the Player deck; the more you add, the more difficult the game will be. (I’ll describe the effects of the Epidemic cards more once you understand how the rest of the game is played.)

Player Turn

A player’s turn is divided into three parts: Perform Actions, Draw Cards, and Infect Cities.

On your turn, you take up to four actions, which allow you to move your player pawn to different cities around the world, build Research Stations, treat diseases, share knowledge (aka City cards) with other players, and discover a cure.

Sharing knowledge is helpful because it gives players a chance to share City cards and more efficiently work towards collecting five cards to discover a cure. Research Stations allow players to more easily move around the world, but they are also a component of the “discover a cure” action. You see, for a player to discover a cure they must discard five cards of the disease’s colour at a Research Station.

The “treat disease” action is especially important in Pandemic. As you play through the game, cubes of the four diseases will make their way onto the board and you’ll want to keep these cubes at a minimum because, the long and short of it is, you’ll lose the game if you don’t. The “treat” action lets a player remove one disease cube from the city their pawn is currently in. If you want to treat a disease that is cured, you remove all the disease cubes of that colour — and if you are ever strategic enough to remove every cube of a cured disease from the board, then that disease is eradicated and you never have to worry about it again. Hooray!

For the next part of a player turn (Draw Cards), you draw two cards (surprise) from the Player deck and add them to your hand, which has a limit of seven cards. If you draw an Epidemic card, that bugger isn’t added to your hand, but gets resolved immediately. (I know you’re eager to learn about epidemics, but I promise it’s coming soon.) If ever you need to draw cards and the Player deck has fewer than two cards in it, players lose the game.

Finally, you must Infect Cities. This is where the game fights back every turn and tries to make your task of saving the world oh so difficult. A player draws cards from the Infection deck equal to the current infection rate and adds one disease cube to the city on the Infection card. The Infection cards are then discarded.

The infection rate begins the game at 2 (so every turn two cities get infected), but it increases with every Epidemic card drawn and can reach as high as 4.

Epidemic Cards

At long last. Epidemic cards have three steps to resolve: Increase, Infect, and Intensify. First, the Infection Rate marker is moved forward one space. Then, to resolve the Infect step, the bottom card of the Infection deck is drawn and three disease cubes are added to the city (instead of the usual one). Finally, the discarded Infection cards (including the one from the Infect step) are shuffled and added back on to the top of the Infection deck.

The player then continues their turn as usual (i.e., moving to part three, Infect Cities).

Outbreaks

Before you go away thinking none of this sounds terribly difficult, let me tell you about outbreaks. If a city has three disease cubes of one colour and you must add another disease cube of that colour (either because of the regular Infect Cities part of your turn or because of an Epidemic card), the cube doesn’t get added and instead that city outbreaks — spreading the disease to each connected city.

Additionally, the Outbreak marker moves one space on its track and if this marker ever reaches the eighth space, you guessed it, players lose the game.

Are you starting to see why treating diseases is so important and how stinkin’ bad Epidemic cards can be? If not, consider the example in the pictures below.

A cube needs to be added to Baghdad but instead it outbreaks, spreading the disease to Istanbul, Cairo, Riyadh, Karachi, and Tehran. Unfortunately Riyadh and Istanbul already had three black cubes so a chain reaction outbreak occurs. The outbreaks for Riyadh and Istanbul are resolved individually, but they won’t re-trigger any city that already had an outbreak.

After resolving the outbreak for Riyadh (pictured in pink), proceed to Istanbul (in orange). Unfortunately in doing so Cairo — a city that only had one cube in our initial picture — now outbreaks as a result of the three other outbreaks.

And this is a very common example of how players can go from doing pretty well in the game to moving the Outbreak marker four spaces and suddenly finding themselves halfway to defeat all in one turn.

If that wasn’t enough to worry you, the disease cube supply for each colour is limited to 24 cubes and if ever you need to add a cube and the supply is empty, you lose!

Game End

Let me take a moment to recap the many ways in which players can lose a game of Pandemic:

- You need to draw two cards from the Player card deck but cannot

- The Outbreak marker reaches the final space on its track

- You need to add a disease cube to the board and the supply is empty.

The only way to win the game is to discover a cure for all four diseases, at which point the game ends immediately so you don’t have to worry about completing your turn and drawing cards that you can’t or infecting cities that would push the Outbreak marker to its final space.

My Ever So Brief Thoughts

I love the giant puzzle that is a game of Pandemic — trying to strategize and cooperatively coordinate which player goes where to optimize their role’s special ability, and deciding which cards to keep for a cure and which to use or discard. Pandemic is a phenomenal game and more than a decade later, its mechanisms still hold up and its gameplay continues to be exciting and stress-inducing.

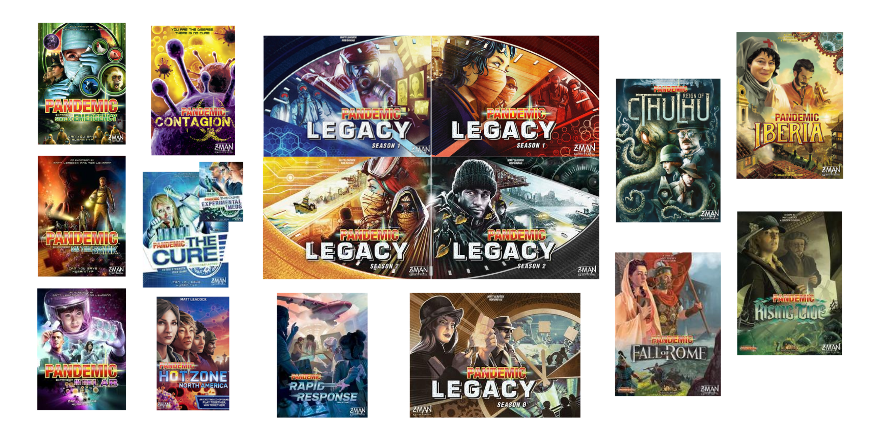

Pandemic’s Legacy

While many modern gamers can surely cite Pandemic as one of their gateway games into the hobby, let’s take a look at just how far-reaching the game’s legacy actually is. Not only has Pandemic sold millions of copies and won a number of awards, but it was so well-received that it has not one but three expansions (On The Brink, In The Lab, and State of Emergency). It also kicked off a spin-off series of games in the Pandemic universe — as part of the Survival Series — featuring guest designers like Jesús Torres Castro (Pandemic: Iberia), Jeroen Doumen (Pandemic: Rising Tide), Paolo Mori (Pandemic: Fall of Rome) and Chuck D. Yager (Pandemic: Reign of Cthulhu).

Fun fact: Pandemic: Rapid Response is not part of the Survival Series; Kane Klenko is credited as the sole designer and not a co-designer with Matt Leacock (like the other games in the series).

Additionally Pandemic has received a “dice game” treatment (Pandemic: The Cure), a digital app implementation, and in 2020 a condensed, quicker-playing distillation sold at big-box stores (Pandemic: Hot Zone—North America). There is also a reverse Pandemic game, Pandemic: Contagion, in which players compete to be the best disease infecters.

Oh, and there were also two Pandemic Legacy games (Season 1 and Season 2), but they weren’t really a big deal…they were a HUGE deal, especially Season 1.

Pandemic Legacy: Season 1 reimplemented Pandemic but also applied Rob Daviau’s legacy campaign model to it. It was so successful that it topped the BoardGameGeek Top 100 only a few months after its release and remained there for just shy of two years when it was dethroned by Gloomhaven on December 29th, 2017. To this day, my gameplay experiences of both seasons of Pandemic Legacy remain some of my most memorable gaming moments. (RIP Eliza.)

It’s easy to see why Pandemic is a game we love and it seems the industry loves it too: four Pandemic games rest comfortably in BGG’s Top 100 and the excitement for all things Pandemic, even in the time of COVID-19, show no sign of slowing down. (At the time I’m writing this, Z-Man Games just released information on the third and final installment in the Pandemic Legacy series, Season 0, which is set to release late 2020.)

Pandemic in Real Life

The COVID-19 pandemic has made life in 2020 unpredictable, difficult, and at times, painful and scary; I think it’s safe to say I never expected the gameplay of one of my all-time favourite board games to be brought to life. While I know the idea of playing a game that so closely resembles your real life experience is probably not many people’s idea of fun (or escapism), Pandemic did help me through the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic — as I mentioned in this piece’s introduction.

Surprisingly I’m not alone in this: Meeple Mountain writer Tom Franklin recently suggested that his friend’s wife might be playing so much Pandemic on Steam as a way “to cope with the changes COVID has wrought” and to “[help] her feel like she’s doing something”. From the stories I’ve heard, she’s not alone.

This has even expanded beyond our hobby. Just weeks after COVID-19 was characterized as a pandemic, I received a slew of messages from non-gamer friends asking if I had heard of or played Pandemic and if I knew where they could buy a copy for themselves. (With the strict self-isolating rules in countries around the world, board games are being played more than ever and, not surprisingly, Pandemic is one of the most common.)

Fun fact: Pandemic recently beat out Catan as the most owned game as reported by BoardGameGeek users (144,855 as of August 2020).

Pandemic, With Love

If you haven’t tried Pandemic yet, you really should because at this point it feels like a necessary rite of passage into the hobby. For me, anything Pandemic will always have a home in my board game collection…even if that means simply letting my completed copies of Pandemic Legacy: Season 1 and 2 collect dust as they sit atop my game shelf in all their splendor.

Add Comment