What happens when two global superpowers clash without combat? What ideology will infiltrate the intellect of the public populace? Find out in our review of Twilight Struggle.

Important Note:

Twilight Struggle depicts and utilizes actual events that affected real people. Many of the events described in this game were horrendous displays of the worst of humanity. Many readers may have been personally affected by these events. As with any game depicting actual historical events, it can be easy to forget the atrocities of the past due to the required amount of abstraction necessary to gamify history. Any amount of levity throughout this review should not take away from the gravity of the subject matter. Additionally, I have no intentions to promote ideological or moral superiority for either side represented, nor do I subscribe to the dangerous notion of moral equivalence. It’s important to remember that often when taking a closer look at the history of humanity, we rarely see true “heroes” and “villains.” I believe that Twilight Struggle handles this concept with a great deal of respect, but it is worth remembering that, historically speaking, mankind’s morality is, to say the least, murky.

Twilight Struggle is a game that attempts to recreate the three historical stages of the Cold War through card-driven area control. However, before we dive into the game itself, a bit of background:

The Cold War was a period of geopolitical tension between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) that spanned from the end of World War II in the mid-1940’s to the fall of the Soviet Union in the early 1990’s. Granted, the term “tension” is a bit of an understatement for something that brought us dangerously close to worldwide annihilation through mutually assured destruction via thermonuclear war. The Cold War was a battle for ideology between communism and democracy. It is referred to as a “cold” war because the US and USSR never physically engaged each other in actual combat, although there was plenty of fighting in other parts of the world that served as proxy wars. The US backed many anti-communist governments and uprisings, whether publicly or privately. The USSR did the same for left-wing parties and revolutions. Both hoped to stop the spread of the opposing ideology across the world.

I’m no historian; the above description is a vast oversimplification of an era containing many moving parts and complexities. This is, after all, a board game review, not a history lesson.

Gameplay

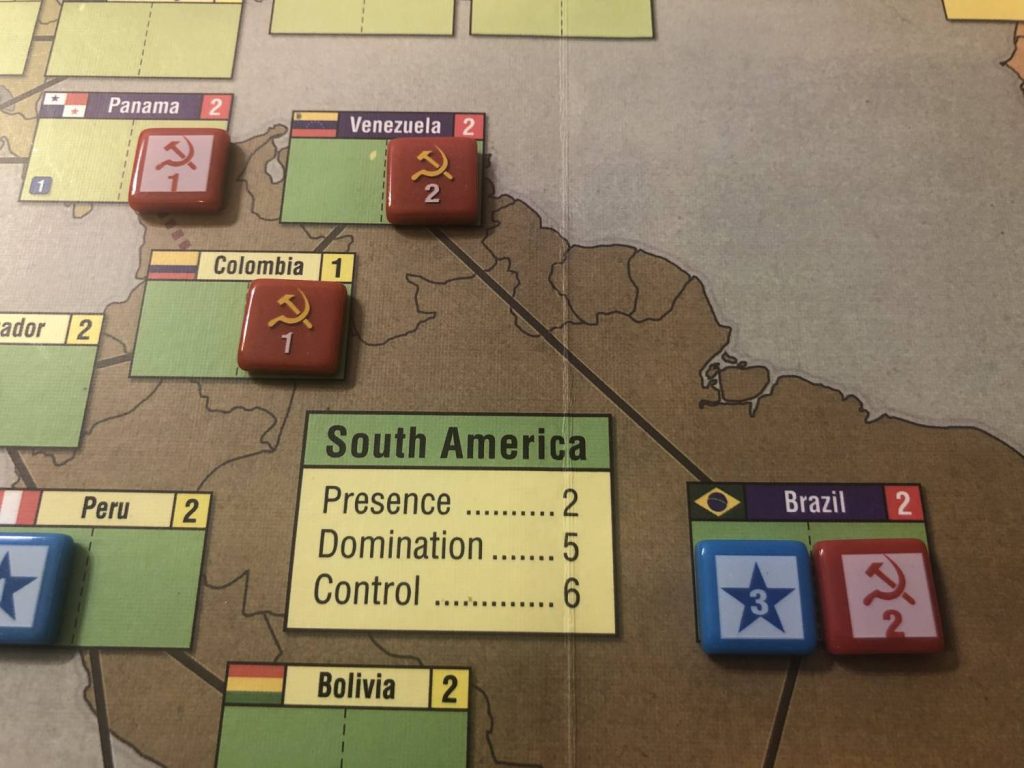

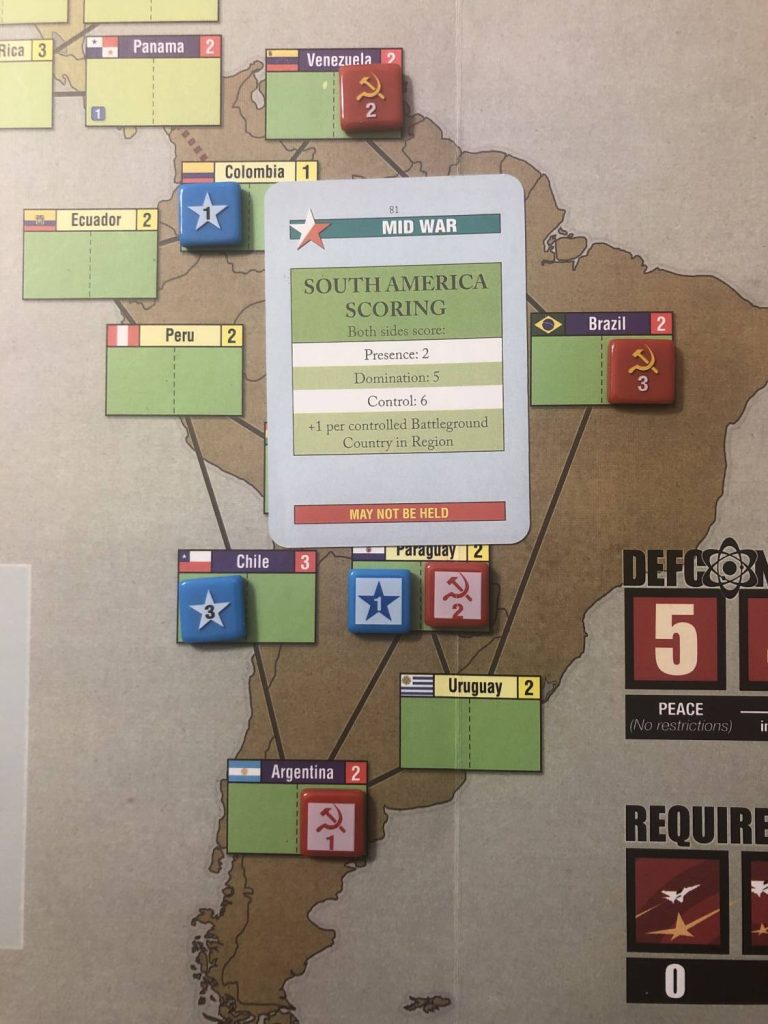

Twilight Struggle is a fairly complex game that can last up to 2-3 hours depending on how the game goes. Although it’s more layered than a buttered babka, Twilight Struggle is at heart an area-control game. The board is divided into several geographical regions, differentiated by color. Each region has a number of countries represented within. While some liberties have been taken with regard to adjacency and geography for the sake of gameplay, it is a mostly fair picture of the world as it was during that time period. In each country’s ‘box’ are spaces for both US and USSR influence, represented by numbered blue and red chits. Each country also has a “stability number” in the top right corner. This number thematically represents how politically ‘stable’ that country’s government is. This will factor into a few gameplay mechanics to be discussed later. Additionally, some countries are denoted as “battleground” countries. Thematically, these represent places where the struggle was most overtly present.

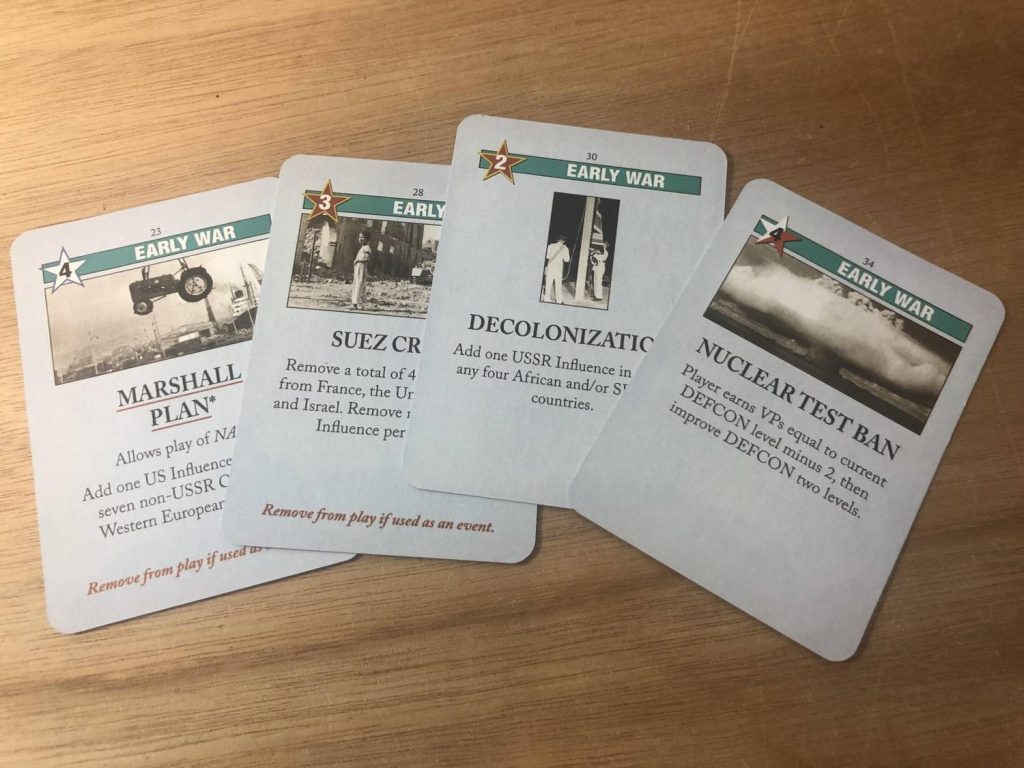

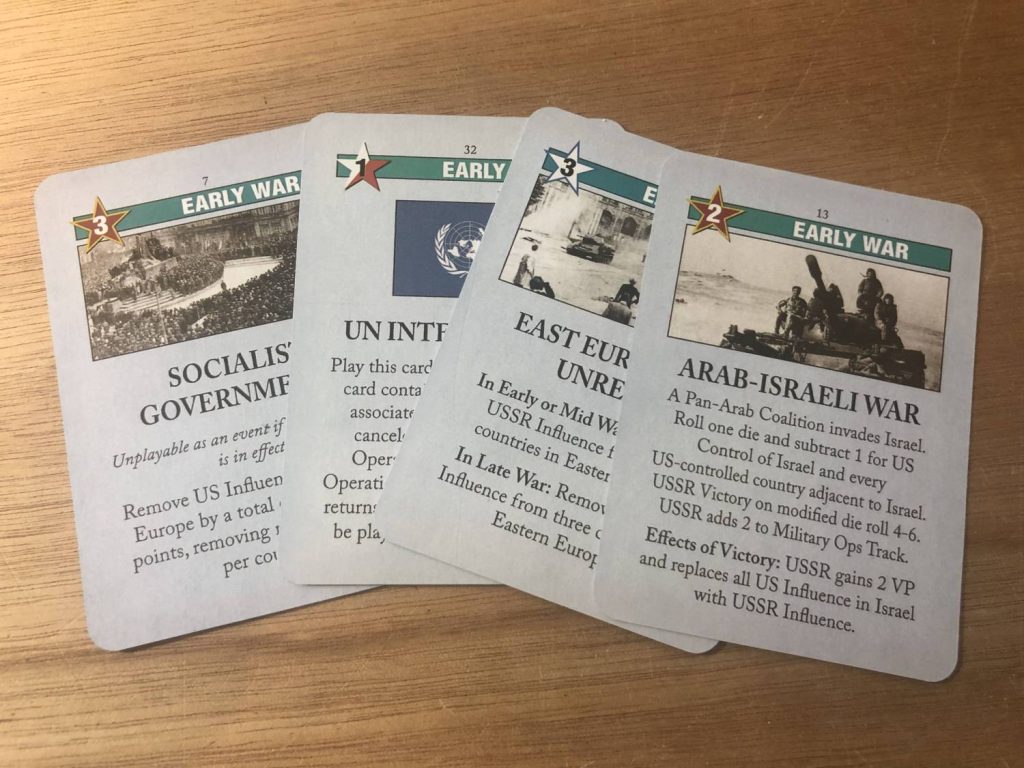

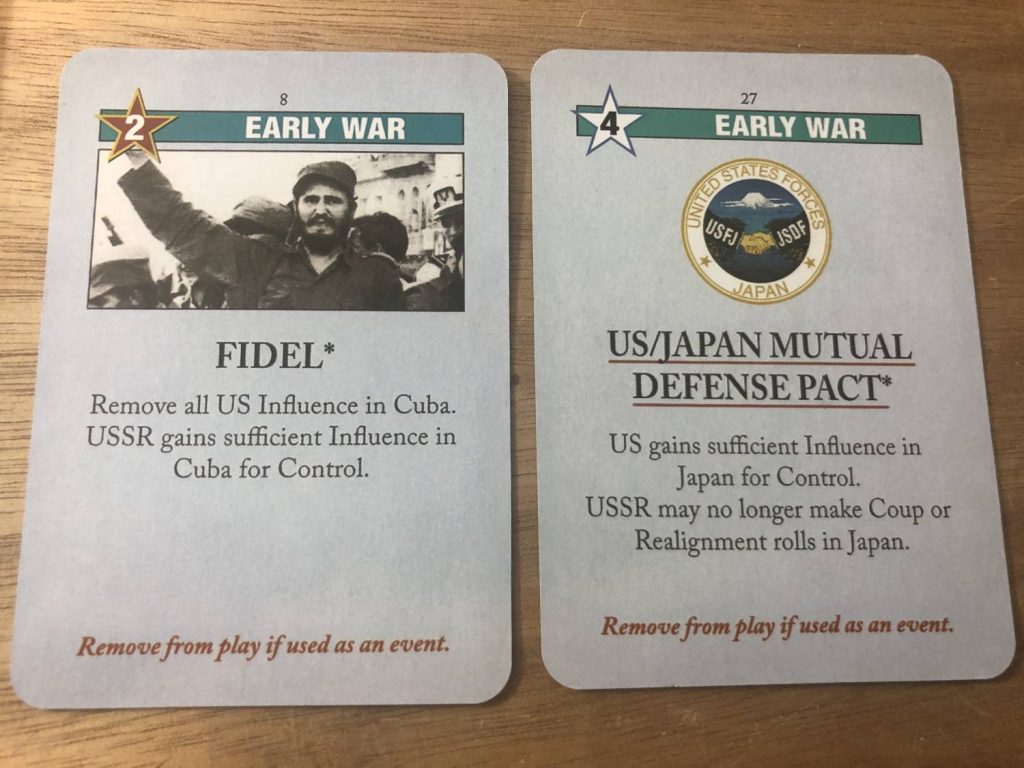

The game is divided into 10 “turns,” each consisting of a number of actions. Players will alternate playing a number of cards (generally between 6-7, depending on the game state) from their hand to improve their worldwide presence, attempting to gain control of countries and regions. On each card is both a historical event and a starred number in the top right corner that represents a number of “Operations Points.” (OP) A card can either be played for the event or for its points. Additionally, cards are often removed from the game if the event is triggered.

The color of the numbered star containing the OP is either blue, red, or a red-white split. Blue cards are generally favorable to the US, red cards to the USSR, while multicolored cards can benefit either side. Here’s the twist: since both players draw from the same deck, you may have a hand chock full of cards with your opponent’s events. You’ll want to play them for their OP, but if it contains your opponent’s event, that will trigger. Playing a card is mandatory, so you’ll often find yourself forced to trigger events beneficial to your opponent. Deciding when and how to play specific cards is at the core of the game’s delightfully devious decision space.

OP can be used for a few different actions, all in the pursuit of having more area controlled whenever scoring comes around. (more on scoring later) The easiest way to distinguish OP actions is to remember “add, subtract, replace, go to space.”

Place Influence (Add)

The first, and most direct action is to “Place Influence.” One OP allows you to add influence to your controlled or a neutral territory, two OP’s to add influence to your opponent’s controlled territory. Influence can only be added into spaces that either you already have influence, or ones adjacent to spaces where you have influence. Thematically, this represents the “domino theory”—that ideas, whether democratic or communistic, tend to spread geographically. You can split up your OP’s however you want to across the world, provided they meet the placement rules. If you have more influence in a space, with the difference being equal or higher than the stability number of the country, you have control of that country. This is represented by flipping the token to the solid colored side.

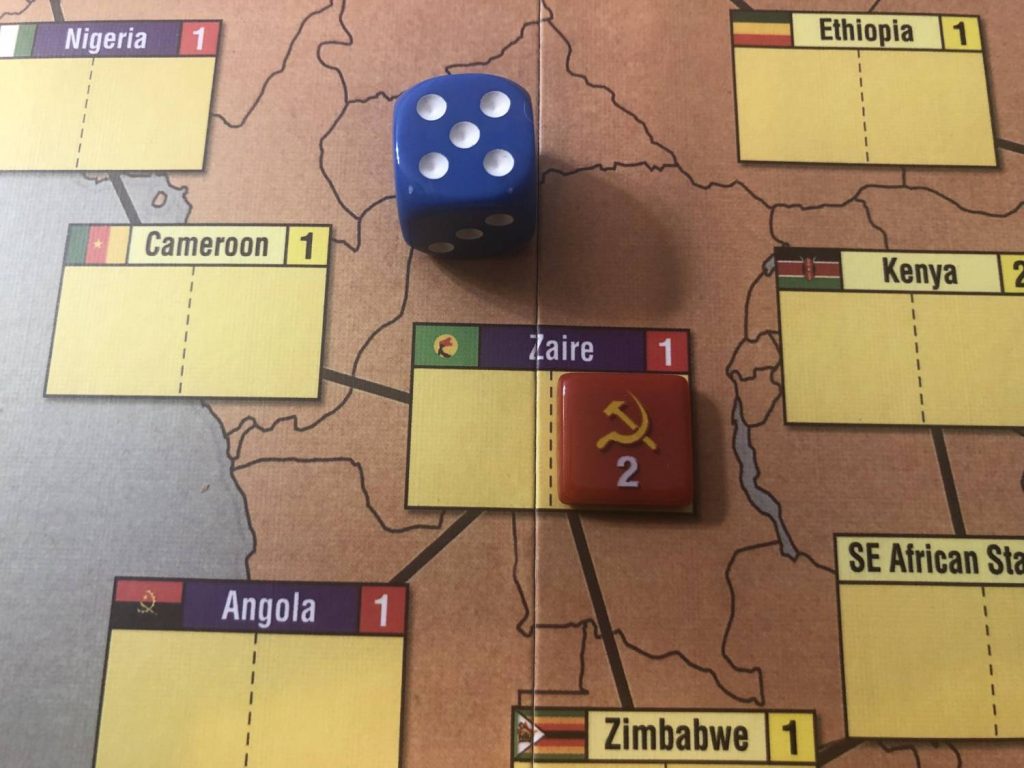

Realignment Roll (Subtract)

The second action you can use your OP’s for is a “Realignment Roll.” This allows you to reduce (subtract) your opponent’s influence from a particular region, according to the results of a die roll, as indicated by the name. Both players roll a 6-sided die. Highest roll wins, and removes as many of their opponent’s influence tokens as the difference between the two rolls. You need not have any presence in that particular country or even an adjacent one. However, you’ll probably want to since you’ll get a +1 to your die roll for each adjacent country under your control, +1 if you have more influence in the targeted country, and +1 if the roll is adjacent to your home country–the US or USSR. Realignment Rolls don’t ever add any influence, only remove.

Coup Attempt (Replace)

The third use of OP is to make a coup attempt. Coup attempts can potentially both remove your opponents influence and add your own. Coup attempts also require rolling a die, but are trickier. The higher the stability number, the more difficult the coup. After all, replacing the government in the well-established UK is a riskier proposition than in war-torn Iran. That stability number factors into the coup attempt die roll like so: the player attempting a coup rolls a die and adds the number of OP on the card being used to attempt the coup. If the result of the roll is greater than the 2x the stability number, the coup is successful. That player can then remove enemy influence according to the difference between the two numbers. If in doing so you take away all enemy influence and you still have some left, you get to add your own, effectively “replacing” them. Coups are a good, albeit more difficult way, to both weaken your opponent’s position and strengthen your own. You can attempt a coup in any country that your opponent has influence.

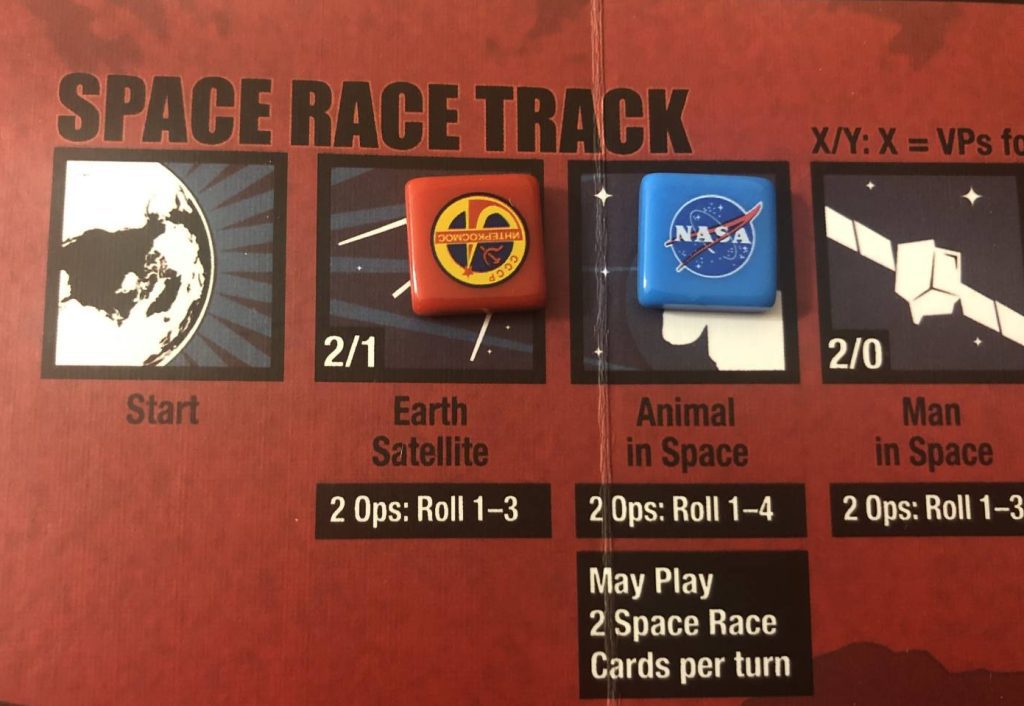

Space Race

The final OP-based action you can take is to dedicate a card to the Space Race track. The Cold War was a time of great—and perhaps childishly competitive—scientific galactic discovery known colloquially as the Space Race. USSR launches a satellite into orbit. The US sends a better one. USSR sends an unlucky dog to orbit, US sends an ape. All of this one-upmanship eventually leads to Neil Armstrong taking that “one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” Obviously, this is an oversimplification of an incredibly complex and nuanced period in history, but a distillation of a zeitgeist to a game mechanic is effectively the point. To use a card for the Space Race, a player may play a card with OP greater or equal to the next step up the track. Roll a die: if it meets the range indicated in the target box, they are successful. Moving up the track grants them points, a special ability, or both. Getting there first generally gives you more points, and the special ability will only last as long as you’re the only one on that step.

Using a card for the Space Race can be extremely advantageous. Not only can you potentially get points and abilities, when a card is played for the Space Race, the event doesn’t trigger. Have a card with an event that is phenomenally beneficial to your opponent? Ditch it to the Space Race. However, until you launch that poor puppy into space, you can only play one card to the Space Race per turn, so choose wisely. The downside to playing cards to the Space Race is that you’re not improving your area control status. An unsuccessful roll can feel like a wasted turn.

Thermonuclear War

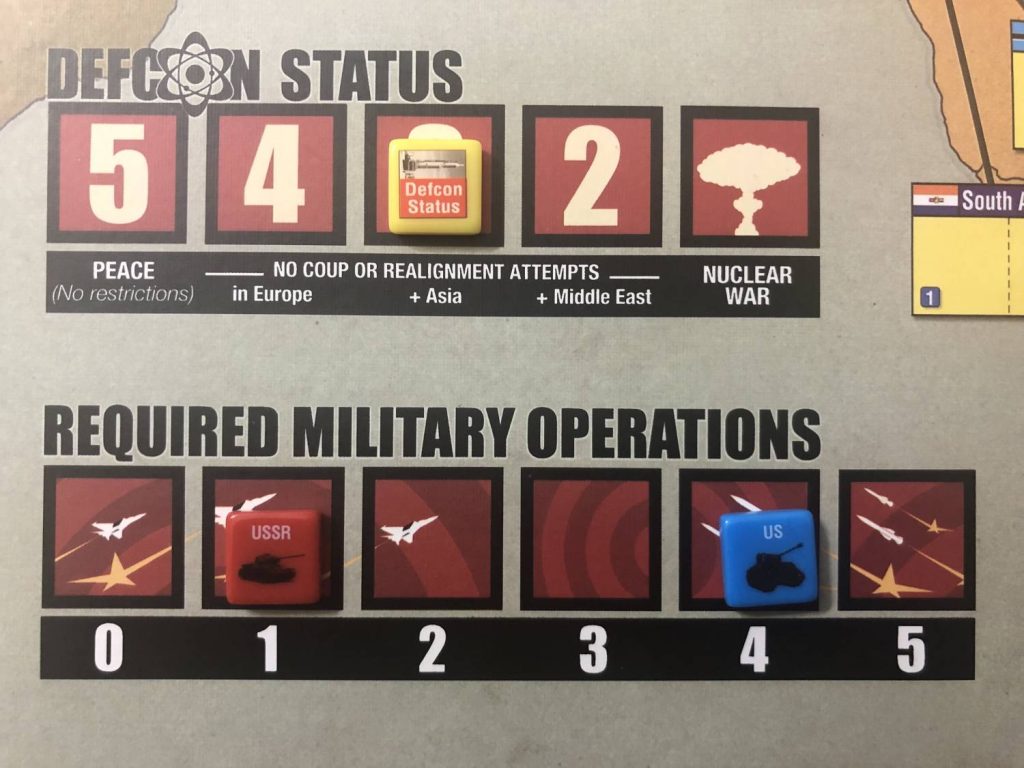

One element I haven’t yet mentioned that plays a key factor is the DefCon track. Thematically, it represents the level of nuclear “tension” present between the two superpowers. It begins the game at the maximum “peace” level of 5. Defcon can go up or down depending on actions and events, but if it ever reaches 1, the game is immediately over. You have triggered thermonuclear war. Mutually assured destruction is, in fact, ensured. Society as we know it is over—make way for post-apocalyptic zombies, if my understanding of movies and tv shows is correct. Whoever the active player was when DefCon 1 hit automatically loses. There is no rewarding the destruction of mankind.

Below the DefCon track is the “Required Military Operations” track. Military operations include Coup attempts or specifically labeled “War Event” cards, provided the event triggers. Each player loses points at the end of the turn for every unmet military operation. The number of required military operations is always equal to the current DefCon level. The tricky bit is that a Coup roll in a battleground country lowers the DefCon level. The trickier bit is that as the DefCon level drops, different regions of the world become unavailable to attempt realignment rolls or coup attempts.

How Do I Win?

It can be argued that historically, no one actually “won” the Cold War. Some would point to the Berlin Wall falling as grounds for a US victory, while others would aptly point out that communism still maintained a significant foothold well after that. But Twilight Struggle is a game, after all, so let’s talk win conditions.

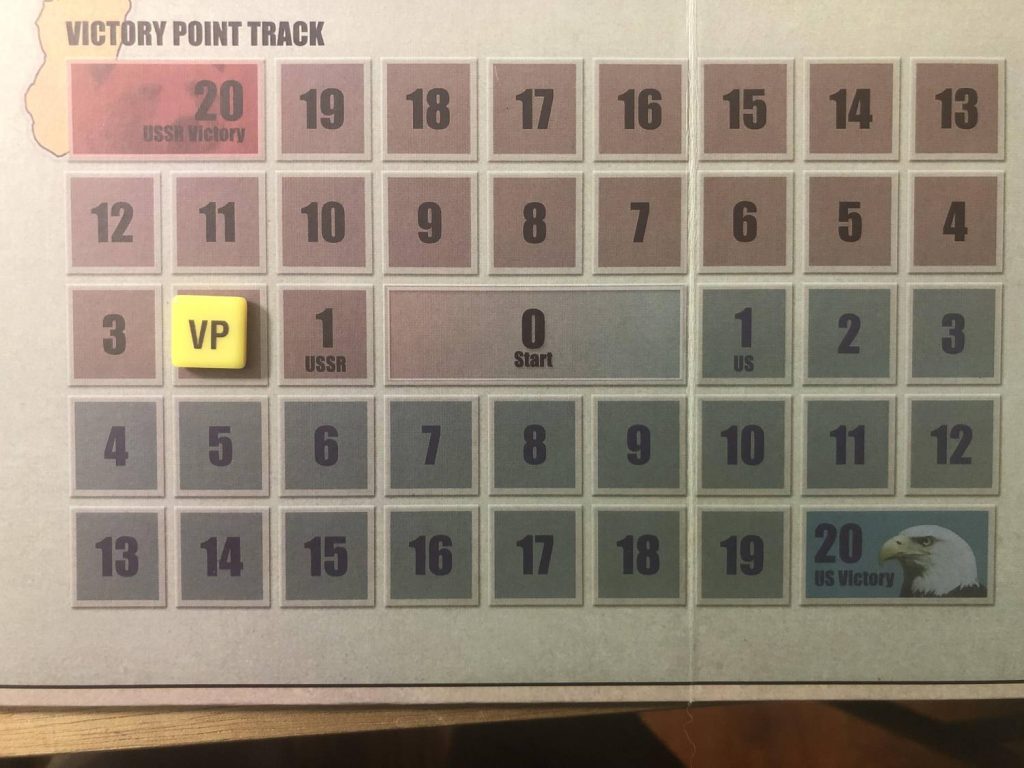

There are two ways to win: Automatic Victory and End Game Victory.

Automatic Victory:

- Either player reaches 20 points.

- Either player controls Europe when the Europe scoring card is played.

- A player automatically wins if their opponent triggers nuclear war by dropping the DefCon level down to 1.

End Game Victory:

If neither side has hit 20 points by the end of the 10th turn, every region is scored. Points are added up and compared and whomever’s side the points tracker ends up is the winner. (If the tracker ends back up on zero, congratulations, you have successfully ended up exactly where you started, accomplished nothing, and the game ends in a draw.)

Okay…How Do I Get Those Points?

The most important thing to know is that this is a tug-of-war. The points tracker starts at zero and will move either way based on points scored.

Throughout the game, in addition to points given on specific event texts, you will be playing dedicated region scoring cards.The order that they come up is random, as they’re mixed into the same decks from which you’re drawing your hand of cards. Some won’t come into play until mid-game, as the decks are initially divided chronologically. If you have a scoring card in your hand, you must play it before the round is over. When scoring, you’ll get points for the following:

- Presence: You have control over at least one country in the scored region

- Domination: You have control of more countries in the region, and also control more battleground countries.

- Control: You have control of more countries, and control all of the battleground countries.

Add an additional +1 per battleground country and +1 if you have control of a country adjacent to your opponent’s home country. Add up the points for each player and move the victory marker the net difference between the two.

Specific point values will vary by region. As mentioned previously, if any player attains Control of Europe (control of more European countries and all the European battlegrounds) whenever the Europe scoring card is resolved they automatically win.

How and when to play scoring cards is one of the most simultaneously impactful and excruciating decisions. Ideally, you’d play it whenever you stand to benefit the most, perhaps hanging on to it until the final action of the round, hoping that by then you’ll be in the best position. Unfortunately, it’s just as likely that you’ll be forced to play it when you know your opponent will score more, with you trying to take a hit on the nose over a punch in the gut.

Final Thoughts

Like studying the complexity and nuance of this historical time period, there’s a lot to unpack. My general consensus is that Twilight Struggle superbly succeeds in being everything that it’s not. I’ll elaborate:

Twilight Struggle is not, strictly speaking, a war game. There are no troops you move across the board, no combat resolution, no player vs player battling. And yet, it is simultaneously the most engaging game involving war that I’ve ever played.

Twilight Struggle is also not an educational game per se, but in playing the game I’ve learned so much about history, and been inspired to read more about the time period and events represented.

Twilight Struggle is also not a real-time game, like Kites, Fuse, or Escape: The Curse of the Temple. Those games rely on a manufactured time pressure to create tension via sand timers, audio recordings, etc. The tension that Twilight Struggle creates, though, is greater than any real-time game I have played.

If the hallmark of a good strategy game is difficult decisions, consider Twilight Struggle a masterclass. Every action you take feels monumental. Being forced to play your opponent’s cards is excruciating. Even playing your “good cards” is a stressful decision tree. Do I use the event, knowing that it might burn the card? Do I use it for its operations points? How do I want to use those operations points? If I boost up my presence in Asia, can I still hack it in Europe whenever that gets scored? Oh crap! Does my opponent have Europe scoring in their hand? I’d better use it in Europe then. But wait, they’ve got dominance right now in the Middle East! What do I do??

Every action you take means you’re not doing something else. Balancing all the globally spinning plates at all times is a Herculean task just short of holding up the earth. The fact that the scoring is a tug-of-war, constantly pushing and pulling, only adds to the tension.

It does have some minor foibles, though, that are worth mentioning. First, it is a bear to learn and teach. Complexities abound within its slew of interlocking game mechanics, even not taking into account the varied effects of played card events. Second, by nature, it has a distinct skill gap. A new player will inevitably get trounced by an experienced one, if for no other reason than a familiarity with the card events.

(For what it’s worth, there is an excellent app version with a good tutorial and challenging AI that can get you over either of these hurdles if you devote the time.)

The final element that may scare some gamers away is the randomness of the die roll. Die rolls determine the outcome of three out of four operation point actions, as well as some of the played events. Mitigation is practically non-existent: you get what you get. My counterpoint to this is that because the die rolls are so ubiquitous and numerous, it balances out in the end. Granted, that still doesn’t feel good whenever all you might need is to roll a 2 to take over Asia and you get a lone snake eye. That level of chaos doesn’t bother me, but to each their own.

Overall, Twilight Struggle is quite simply a masterpiece of game design. There is a reason that it held the #1 spot on BoardGameGeek.com for years. The way that the game thematically captures the subject matter while simultaneously providing constant engagement in its game mechanics is just spectacular. I play against the AI on the app at least twice a week, and would happily play it on the table any time. It’s an easy 10/10 for me. I highly recommend that everyone try it at least once, even if the theme or style of game may not be your bag. It’s just that good.

Wow, 17 years late to the party lol.

Better late than never with a classic like Twilight Struggle. In addition to it being a good game, publishing a review allows us to crosslink this page from other pages on the site.