Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I’m sure they pre-exist my observation, but 2025 is certainly the first year I became aware of semi-cooperative worker placement games. I’ve played two so far, and I’m confident that we’ll manage to sneak one more in under the wire. So far, results are mixed. Kinfire Council is a much more interesting idea than it is a game, and the same seems to be true of Winter Rabbit.

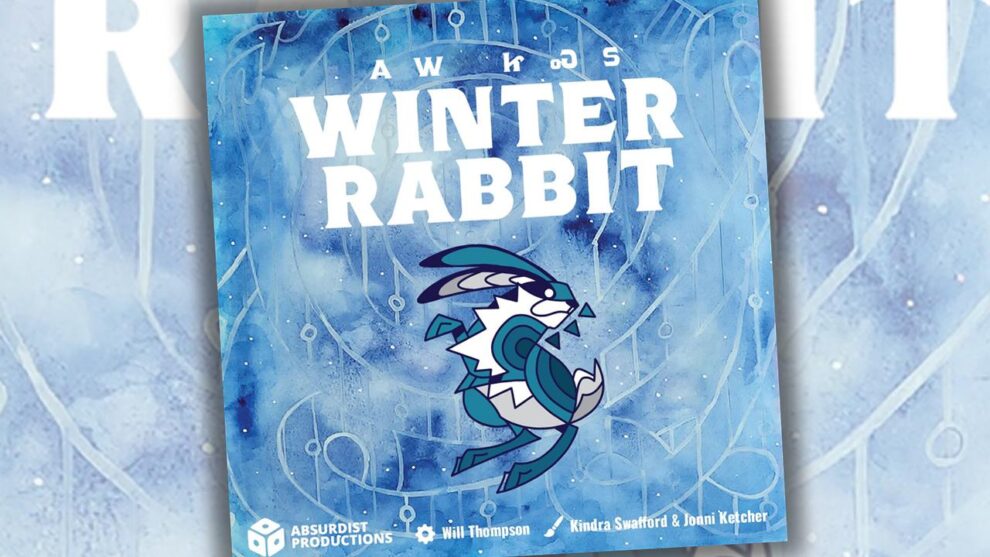

Designer William Thompson’s game first came across my radar when it was a finalist for the 2021 Zenobia Award, which aims to raise the profiles of underrepresented game designers. The Zenobias are worth watching because the cause is worthwhile, but they’re also worth watching because the games that come out of the shortlist present us with settings and themes—actual themes, not window dressing—that don’t normally make it to market. In the case of Winter Rabbit, we find ourselves in Cherokee folklore, with Otter, Deer, Terrapin, Bear, Wolf, and Opossum preparing for winter.

The worker placement here is not quite like anything I’ve ever seen. The core of the game is simple resource conversion; you accrue various resources and then spend them to gain upgrades and points. The method is what’s novel. Players draw workers out of a communal bag. They may draw their own worker, but it’s more likely they’ll draw somebody else’s, or even that pesky Rabbit. More on him to come.

The worker placement here is not quite like anything I’ve ever seen. The core of the game is simple resource conversion; you accrue various resources and then spend them to gain upgrades and points. The method is what’s novel. Players draw workers out of a communal bag. They may draw their own worker, but it’s more likely they’ll draw somebody else’s, or even that pesky Rabbit. More on him to come.

Once drawn, you place the unrevealed worker facedown on any space on the board. Each of the board’s six sections corresponds to one of the resources. When all the empty spaces of any one section are full, that resource produces. The discs are revealed and, barring the presence of the Rabbit, everyone receives one of that good. The player(s) with discs present gain(s) one extra resource per disc. If a Rabbit disc is revealed, he nabs all the resources for himself, running them to his warren. Oooh, that wascally wabbit.

The cooperative aspects of the game come from Tasks, which players play from their hands at the top of each round. Each Task requires a certain number of resources to be completed, and scores the completing player points, but you can’t complete your own Tasks. Someone else has to do the hard work for you. They get points, and you get a small bonus.

The cooperative aspects of the game come from Tasks, which players play from their hands at the top of each round. Each Task requires a certain number of resources to be completed, and scores the completing player points, but you can’t complete your own Tasks. Someone else has to do the hard work for you. They get points, and you get a small bonus.

Every Task completed also helps move the collective towards winter readiness. By the end of the fourth round, the group has to have completed seven in each of the three categories in order to make it through the winter. If that happens, the player with the most points wins. Otherwise, you all go down together.

There are promising elements here. I love the idea of drawing and placing any player’s worker. I think there’s a great game to be made out of that, but Winter Rabbit isn’t it. Much like Kinfire Council, the politicking that the manual encourages never manifests. It’s all pleasant, but it’s rarely compelling.

There are promising elements here. I love the idea of drawing and placing any player’s worker. I think there’s a great game to be made out of that, but Winter Rabbit isn’t it. Much like Kinfire Council, the politicking that the manual encourages never manifests. It’s all pleasant, but it’s rarely compelling.

The production and art are beautiful. I love the art, particularly the designs of the creatures, but it’s rarely a good sign when the art is my favorite thing about a game. Despite a promising setting and an unusual dynamic, Winter Rabbit doesn’t manage to come together.