In my Wednesday game group, we usually have enough players to do two games. During a recent get-together, two games were set to hit the table: Tyrants of the Underdark (a deck-builder that, like my friend Andrew Lynch suggests, is a terrible-looking production packaging a very good game) and Whistle Stop, one of the faves of the host that night.

“I’m torn,” my friend Stephen said to the room. Stephen likes area control games—Tyrants checks that box—but he is also the guy that brings his copy of Age of Steam every week. “I haven’t played either, but I would like to try both. Which one should I pick, knowing that I am a train gamer?”

“You should play Tyrants,” said, naturally, the guy who brought Tyrants. “Whistle Stop is more of a game with trains, rather than a train game.” (This is the kind of “gatekeeping” I see in lots of groups, including my own!)

No matter where you land, Whistle Stop is a game that features trains. In our group’s vernacular, Whistle Stop is not a “train game”—there are no stock rounds, operating rounds, trains that rust, or phases where we switch from green to brown track. But it is absolutely a train game in the way that Age of Steam operates, for some of the reasons we will discuss below.

Watch That Track Go!

Whistle Stop (2017, Bezier Games) is a pick-up-and-deliver route-building game for 2-5 players. Over a series of rounds, players will lay track from a choice of three hand tiles to help their trains slowly move westward to deliver goods and score “fame points” (victory points). Along the way, players must spend coal tokens as action points to navigate a fun maze of track spaces—where players can either gain goods or use town spaces to buy stock, trade goods between types, acquire whistle tokens which can be used to boost movement, or even collect gold, which are special tokens worth fame points at the end of the game.

All of this is packaged in a game that can be taught in about 15 minutes and played, even in my recent five-player game, in about 90 minutes. Whistle Stop came out a lot in this gaming group when it first hit the market eight years ago. Now, with many of us being more attuned to cube rails titles on weeknights and 18xx games or heavier fare on weekends, Whistle Stop has not gotten the love it deserves (so thanks, Nate, for getting it to the table!).

But that is a shame, because many of the supposedly-legit “train games” do many of the same things Whistle Stop does, even if Whistle Stop doesn’t always do them as consistently well. (Age of Steam features some of the same pick-up-and-deliver elements that Whistle Stop does, just moving cubes around in a different format. Also, Whistle Stop’s color schematic looks eerily similar to the graphic design used in Age of Steam.)

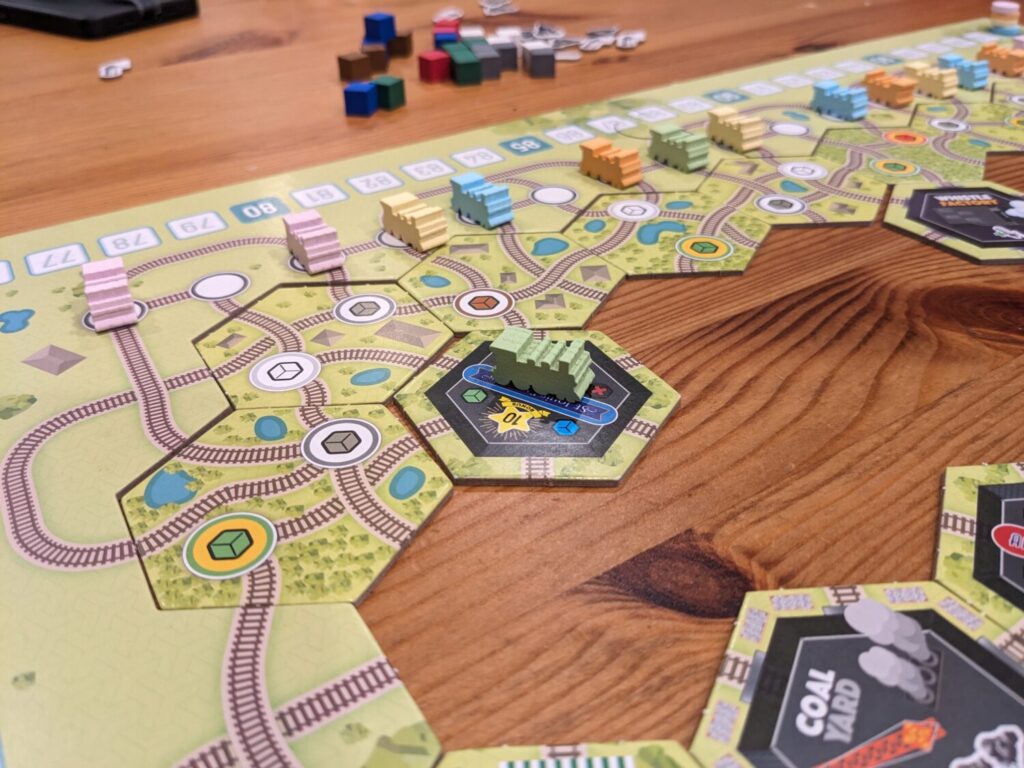

Whistle Stop’s main strength is its map, in part because the map features a variable setup. Maps that are heavier on Coal Yard tiles—which grant a bonus of two coal tokens when visited, helping to boost current and future turns—lead to faster play. Players have a hand of tiles, but can play them onto the map whenever they need to move their trains onto spaces that have not yet been filled by an opponent, offering very handy, real-time flexibility.

Tiles are a mix of plain track, track with resource stops (featuring one of six different resources), and special tiles, which include towns (where shares of five different companies can be purchased with goods), a General Store, and a Trading Post. Because of the random distribution of those tiles, I have always enjoyed the elements that change from game to game. Stock, in particular, can be wildly variable. If a savvy player places a town tile for, say, the Coast-to-Coast corporation behind the position of other players’ trains, then buys a share from there and never places the second Coast-to-Coast tile on the map, they quickly find themselves holding a majority position in a company that no one else can grab for end-game scoring.

And players with the right mix of resources can speed one of their trains all the way to the end of the map to claim an instant bonus whenever they want, assuming they have the tiles to move their trains quickly. Whistle Stop can end as soon as any player gets all of their trains to the western-most end tiles, so rushing the ending is absolutely on the table.

Whistle Stop also has some teeth to it—negative points are scored whenever a player visits a town tile and cannot afford to buy a share there, in a game where each action point is very valuable. Losing even 3-5 points in this game could cost you the win.

Because resource stops cannot hold more than a single train, players constantly have to pivot to find their way around each location. Whistle tokens are available, but in limited supply…and whistle tokens allow a player to not only move two spaces instead of just one, but also move eastward. In a pinch, moving backwards to grab a resource that can later be spent by a different train racing to the finish line can be situationally huge.

“Wait…What Happens to My Shares?”

Some of the elements that don’t work for me now are tied to my current infatuation with traditional train games, particularly tied to stock. In Whistle Stop, shares are just shares, with values that don’t exist in the traditional sense. There are five shares in each company, and only the person who has the most shares will get a scoring bonus when the game ends.

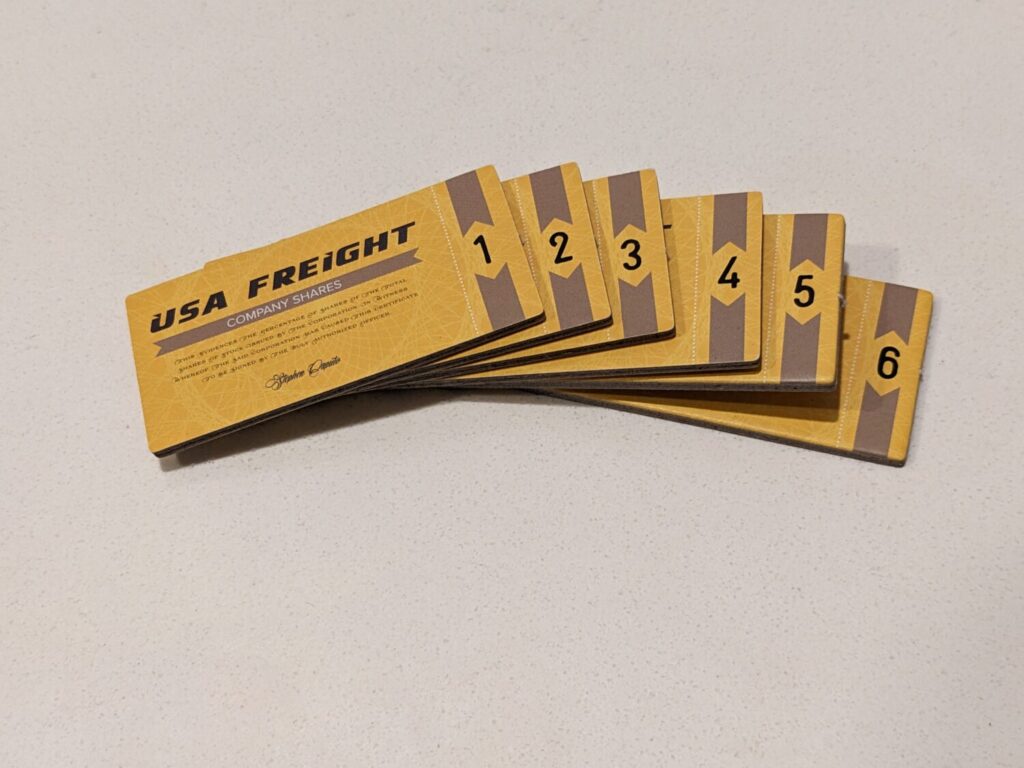

But the person who buys shares in each company the earliest will win a tiebreaker for a pretty sizable number of points (15, in a game where scores for the winner land in the 80-100 range). There is a somewhat decent workaround—one of the western-most end tiles allows a player to score points based on the number of shares they have, while also forcing that player to remove one of those shares from the game. If it is looking like I’m going to finish second in the race for shares of, say, USA Freight, that might be the time to dump a share…but that doesn’t hurt the overall value of USA Freight, which I don’t love.

Still, I’d rather have 15 points for the work I put in as an investor, on top of any points scored when I bought the shares. That might mean, in the example I provided earlier, that someone might get 15-30 points simply due to the luck of the draw with tiles distributed during setup. In fact, the tile flop in general will rankle some players. The face-up market of three tiles available to draw at the end of each turn might feature plain track, or the specific red cube you were looking for, or a special tile that is a Gold Mine…not all tiles are created equally!

There are upgrade tiles in Whistle Stop, which can be purchased with common goods (brown, white, and gray cubes) during a player’s turn. These introduce cool powers that can also be “stolen” from another player…by paying the cost the original player paid to the supply, plus an uncommon good (red, blue, green) to the player being robbed.

That’s not a bad deal for being robbed, so getting in early on the upgrade tile game is a smart thing to do. However, some of those tiles are patently better than others. Coal Car lets a player turn a coal into two coal, in a game where coal can be pretty tight. If that one is in the game, it always goes first. (Players normally only get two coal tokens per round, but can save any leftovers for future turns.) Mine Cart, Blocking Signal, and Compass are all exceptional, and not situational–they are always useful.

Although my findings are limited here, my sense is that Whistle Stop is a game that favors the experienced player, especially ones who understand the full-game value of upgrade tiles. These tiles are also worth points at the end of the game, so going for them early and finding ways to have some by the end of the game is always worth it.

The Breeze Line

Whistle Stop holds up, eight years after its initial release. There are plenty of ways to score if your plans to buy up a bunch of stocks are derailed, and I like games that have a variable number of rounds. Because of the random distribution of the track/town tiles, every game of Whistle Stop is guaranteed to look just a bit different from each other.

For the serious train gamer, I found both in the example above and with games like Empyreal: Spells & Steam that hardcore choo-choo players should look elsewhere. In fact, some of my train game friends believe wholeheartedly that train games have to feature money, and there is zero cash included in a play of Whistle Stop. For that reason, train gamers looking for lighter fare can safely stick to the cube rails experiences I’ve recommended in the past, or route-builders like the Brass/Age of Industry system instead.

For me, a guy who will play any kind of game, including ones that are simply not serious enough for a hardened 18xx or SICS (“shared incentives and common spaces”) player, Whistle Stop is a great weeknight route building game. While I’ll grant you the lack of a “wow” factor with this design, the map and the upgrades shake up each game of Whistle Stop in a package that plays in about an hour. Mixed in with lighter, “long filler” fare like Village Rails, Whistle Stop is worth a look and is another great-looking production from the team at Bezier.