Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

If you’ve ever tried pushing two drinking straws into a mound of mashed potatoes from opposite sides, hoping they’d meet in the middle, you’re already halfway to loving 1987 Channel Tunnel. And if you’ve not tried, have you really lived?

Two nations boring a tunnel 50km in length to a depth of 75km below sea level, each headed right straight for the other, give or take two feet. Now that’s drama. It’s also one of mankind’s greatest achievements in engineering. The Channel Tunnel is actually an interconnected set of three tunnels that pass under the English Channel connecting Britain and France. Two primary tunnels carry high-speed train traffic back and forth while a third service tunnel travels between. If you’re interested in how such a thing came to be, a visit to YouTube (after reading this review, of course) will serve you well.

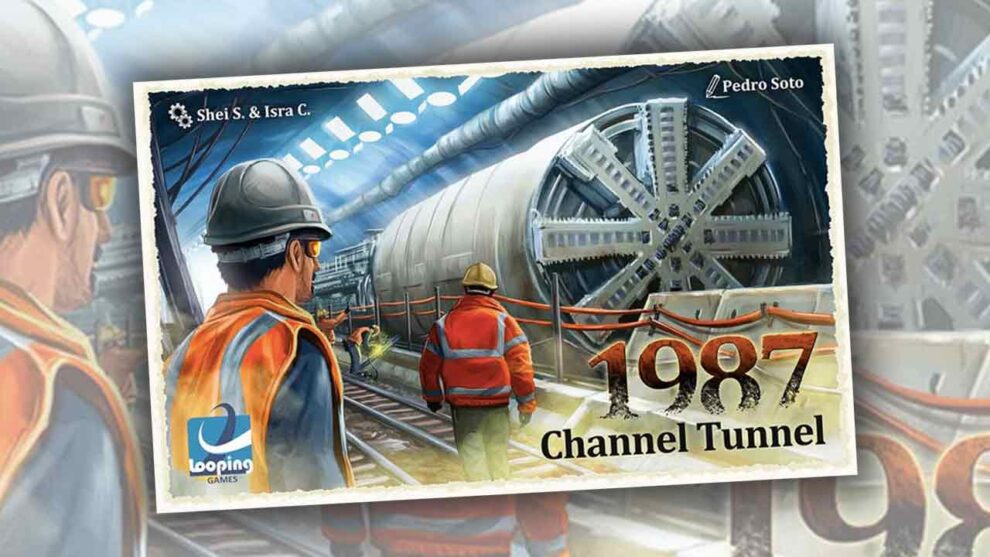

1987 Channel Tunnel is a 2019 release from Shei S. and Isra C. (The Red Cathedral, White Castle) that seeks to mimic the nationalistic competitive streak that drove the Channel Tunnel to completion. Two players, as France and Britain, bore toward one another while engaging in struggles over diplomacy, financing, and technological advancement. The first player to the center triggers an immediate end.

Historically concerned

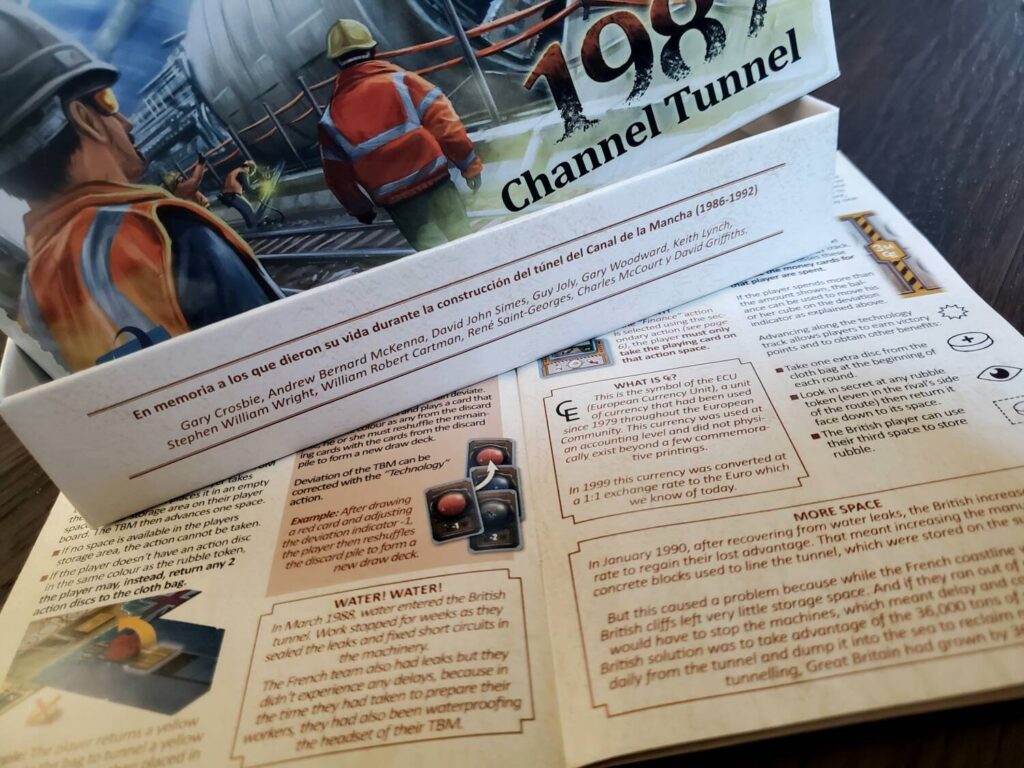

With their 19xx titles, Looping Games has proven time and again their care for history. One side of the box bottom lists the names of the workers who died during the construction of the Channel Tunnel, giving the game an unexpected heft from the beginning. The rulebook is littered with tidbits about the project and the mechanics definitely evoke the historical moment.

The two sides have player boards connected by a series of cards depicting the channel. Small debris tiles are turned face down in a line between the players so that they start the game separated by water and uncertainty.

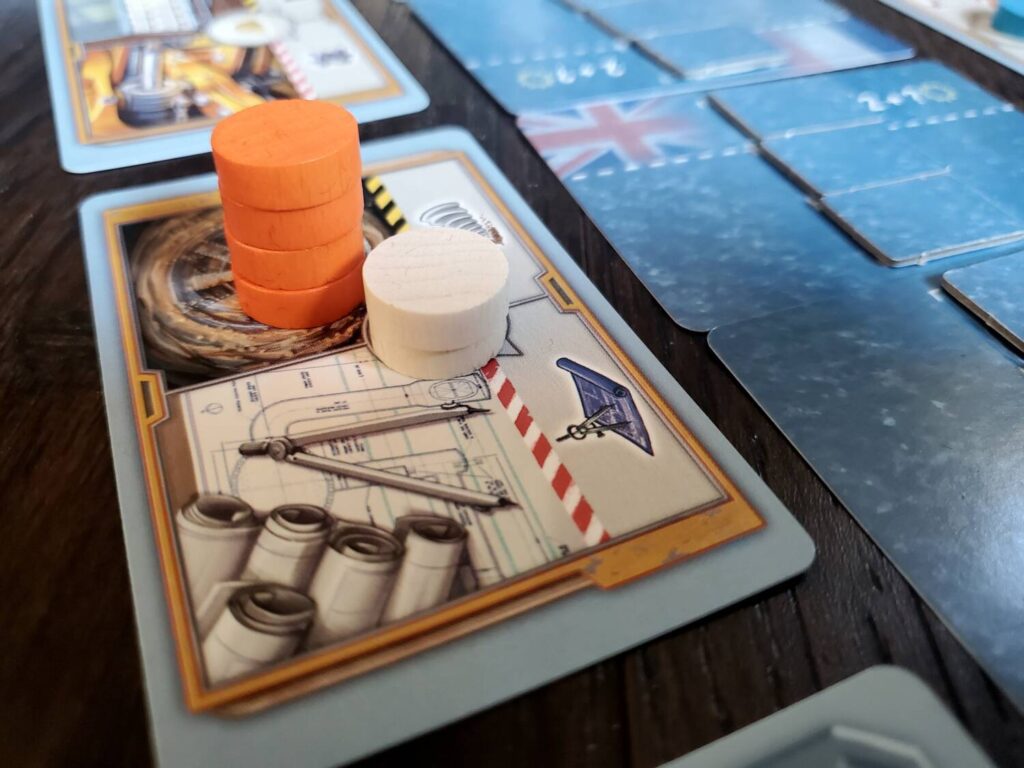

Players lay stacks of discs on one of five action spaces until they pass, thus ending their round. If a stack of discs has already been placed on an action space, a player can lay a larger stack to claim the action, taking the smaller stack into their possession, bolstering an existing stack if they still have the matching color. This push and pull is the central mechanism and the key source of tension throughout the game.

Further stretching that tension, the action spaces are divided to enhance the fight. The Plan action, which reveals the next face-down debris tile on the Channel, shares a space with the Tunnel action that removes the debris. The Finance action, which collects cards as cash to spend on advancing Technology, shares a space with the selfsame Tech action where money is spent. Likewise, three additional spaces give the opportunity to either collect/purchase a card or discard it for its base action.

Historically driven

The cards in 1987 are stunningly quadrupled in function. They serve as cash when collected via the Finance action. They provide one of the four aforementioned base actions when engaged as such. They provide potent single- or double-use in-game actions when purchased for their unique icons. After all that, their endgame points are the icing on the cake. Those final three action spaces are simply places to engage the many options of the cards.

Those unique icons are not terribly unexpected. Flags represent the various diplomatic efforts during the process as players collect allies. Other cards gamble on the acquisition and distribution of flags. Topographical analysis cards hold different debris samples and reward the number collected. Special actions are one-off boosts: an extra placement disc or a doubled Tech action, for example. Chained actions are “when-then” cards: when you X, then also Y.

Tunneling requires a sacrifice—payment of one disc matching the color of the debris. The payment weakens a stack but advances the Tunnel Boring Machine (TBM) one step towards conclusion. The boring player also draws from a short stack of deviation cards that indicate movement off track. Moving too far off track results in instant defeat. Here, the historically driven asymmetry kicks in. Britain struggled with water in their boring process. France did not. So when the British side encounters water, the player draws two deviation cards where France draws none. Both players, but especially Britain, need a constant eye on the short stack of deviation cards (always remembering the values that have come out) and a constant need for cash to mitigate the deviation.

The Tech action comes with the opportunity to reduce deviation and improve options. Moving up the Tech track results in more placement discs for each round, the occasional peek at upcoming debris, and endgame points. In Britain’s case, the Tech track also opens a new location to unload debris.

Debris serves as a currency in the game for the purchase of cards. Debris is gained through drilling. During the carving of the tunnel, Britain was short of shoreline to dump the extracted materials. Fittingly, Britain begins the game with one less storage space for debris. However, Britain grew by over 100 acres during the boring process from all the debris deposited purposefully along the shoreline. That extra storage space opens via the Tech track.

So far, it sounds like Britain is at a disadvantage with the water issue and the space issue. The equalizer is in the distribution on the Tech track. Every so often, players need an amount of cash to continue on the track. Britain goes farther earlier and pays less to do so. Their historical head start thus comes to life. By the game’s end the amounts even out, but the distribution definitely favors the British side early to balance the situation.

Players continue in this pattern until someone reaches the middle, at which point a final bonus is unlocked—points for speed and points for the opponent’s untapped debris tiles. Cards grant a load of points along with the Tech track. Deviation is a loss on the scoreboard. The player with the most points wins.

There is an expansion module included in the box, called Agenda, that I can’t bring myself to try. The dastardly little clipboard cards introduce some sort of punitive objective that must be accomplished or else. Something like that might work for some, but not for this boring guy.

Historically worthwhile

1987 Channel Tunnel is one of the best two-player games I’ve encountered.

Thematically, this one is off the charts. Not only do I love the asymmetry, I love that the asymmetry tells the story so faithfully. I can’t say there is a feature of the game that feels arbitrary or unnecessary. In my early plays we made a few small rules gaffes (none that substantially altered the experience), but when we course-corrected, I found myself saying, “That makes perfect sense. Of course!” The game just keeps getting stronger.

On the table, 1987 looks inviting. The I-beam layout of the player boards and channel is interesting and begs investigation. The action space cards fit workably into that layout, building a cohesive play area with space for everything. Looping has found a way to build that large board feel without the bother of the actual board.

The bag included for drawing discs every round was utterly shredded after the second play. Plan to replace it early if you hunt down a copy. The art from Pedro Soto is serviceable but hardly stunning. I recognized Margaret Thatcher and Francois Mitterand, so it works. The Tunnel Boring Machine piece is evocative, even if its shape doesn’t match its real-life counterpart. The discs are discs. The production is appropriately simple.

The disc placement mechanic is a gem. The tensions are real on several levels. By starting with a bag draw, there is just no way to predict strengths and weaknesses, keeping players on their toes from start to finish. In principle, it’s easy enough to believe you’ll start with the small stacks and work your way up. But if my small stack is orange, and France over there has a 2-stack of orange, I don’t necessarily want to allow that exchange to beef up their future efforts. Of course, then I look at their deviation track and realize they need to take a Tech action to pay it down and I think about possibly getting in the way with a large stack. Or maybe I see they can’t Tunnel without a yellow token—I don’t want to lay out a disc for them to claim and use later. Such an action might force them to discard two others in exchange! Every decision has a fantastic ripple, both in the actions and in the doors the placement might open for the opposition.

The cardplay is a series of snowballs. If I start grabbing topographical survey cards, my opponent will have to interfere or potentially surrender too many points should I claim them all. The case is similar with ally flags: if someone lays hold of a stack of flags and the bonus for most flags and the bonus for each flag in possession, the game might be over. Then again, there’s only so much debris to spend and all those bonus action cards are mighty useful and score a point or two themselves. The choice to chase one or chase all makes for a silent, but fun, interaction.

Tunneling is the ever-present economic aim. Boring brings debris which buys the cards which drive the action and the scoring. In the absence of any genuine tugging, I guess you could call it a push-o-war as the TBM’s move closer and closer to the center. The action combined with the visible representation form a nice story arc right there on the table.

The fun hiccup with this box was the rulebook. When the game arrived, the rules had been stapled with every other page rotated 180°. The pages alternated between English and Spanish, a truly multi-lingual book. It was a quick repair with a full-sized stapler, but every time I open the book I can’t help but smile as I remember.

Historically memorable

Looping’s 19xx series is growing in my estimation with every play. 1923 Cotton Club ticked all the same boxes in the same way. 1902 Méliès and 1920 Wall Street are following suit. Small boxes, thematic richness, historical conscience, fitting mechanics, and play times to match the overall ethos.

1987 Channel Tunnel should definitely be on your radar, especially if you spend a lot of time with two-player titles or if you are intrigued by the modern marvel that is the Channel Tunnel.

As I work my way through the Looping 19xx series, I’m keeping my thoughts in order with a ranking. I will provide that ranking with each review:

- 1987 Channel Tunnel

- 1923 Cotton Club

- 1902 Méliès

Add Comment