Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

As we continue our goal to cover the top 500 games on the Board Game Geek list of their most popular titles, two somewhat startling revelations occurred earlier this year:

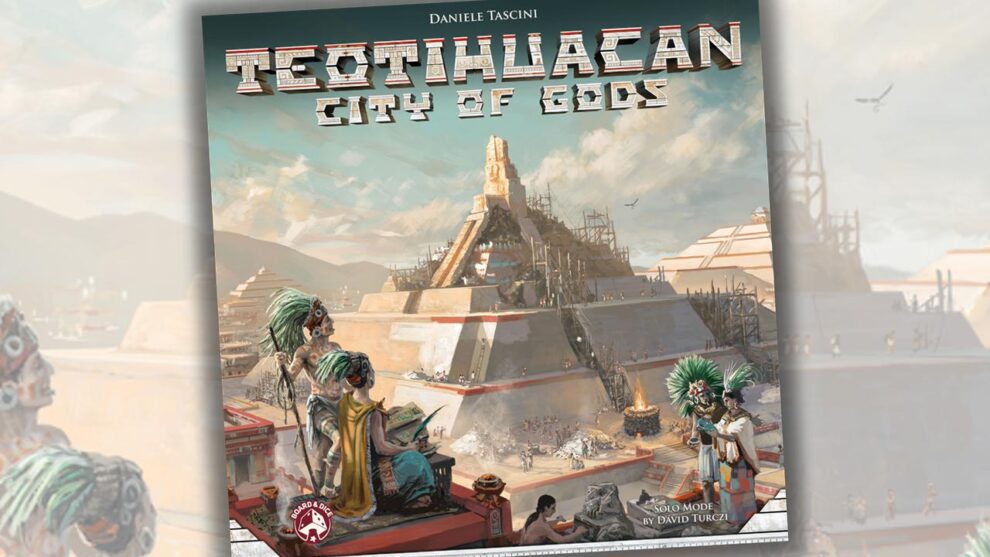

- We had not previously covered the 2018 release Teotihuacan: City of Gods, designed by Daniele Tascini. Teotihuacan is so “old” that it was technically published by NSKN Games in 2018 before NSKN merged with Board&Dice, the publisher of many solid medium-to-heavy strategy Euro games based in Poland.

- Despite being a fan of some of Tascini’s other titles, including Marco Polo II: In the Service of the Khan and Tiletum, I did not own a copy of Teotihuacan.

As of late April 2025, Teotihuacan holds spot #99 on BGG’s list of the most popular titles amongst its user base. In many strategy gaming circles, Teotihuacan is still a legend. Over the course of four fresh plays for this review (three in-person plays at two and three-player counts, and a three-player game on Board Game Arena), and referencing my first play of the game at a friend’s house pre-COVID, I needed to know: does Teotihuacan hold up?

Teotihuacan is Still Really Hard to Pronounce

Teotihuacan: City of Gods is a 1-4 player game that features a load of mechanics. At its core, it is a rondel game featuring dice worker placement. Despite a somewhat dense rulebook, the game can be taught in about 15 minutes even to casual hobbyists. Over the course of three eras, known as Eclipses, players take turns moving around the rondel to collect resources, research technologies, and help decorate and build a pyramid that slowly rises in the middle of the main board.

Workers get stronger during play, slowly upgrading their starting pip value from one to as many as five before “ascending” into the heavens, granting a player significant one-time bonuses. Teotihuacan is also a “feed your workers” game, meaning that players need to manage cocoa, a food supply for both main action selection as well as end-of-Eclipse salaries that must be paid in food to avoid a major hit to a player’s score. (This is similar to Tascini’s approach to his earlier co-design Tzolk’in: The Mayan Calendar.)

Certainly, there’s more to the game than that, but, not really. What really struck me with my most recent review plays for the game was how simple each turn’s choices were: move a die one, two, or three spaces in a clockwise direction, then take an action to either get cocoa, take a main action, or “worship” at a space by burying a die to collect bonuses at a location.

And almost everything is tied to cocoa. In any Euro-style efficiency puzzle, you want to spend as few actions as possible on maintenance steps such as acquiring cocoa, so finding a way to max your cocoa pickup is crucial. Want to take a main action? That will cost you one cocoa for every player color at a location, including your own! Want to temporarily bury a die in a locked worship space occupied by another player? You have to pay to kick the other player out first, which might save the kicked-out worker’s owner three cocoa. You could unlock all your locked workers at once, but if you are short on cocoa, that will cost you your entire turn.

Teotihuacan (tay-uh-tee-waa-kaan) is a hard word to say. It’s even harder to spell. But in game form, Teotihuacan is a surprisingly easy game to teach, especially when you focus on a different word: food!

Teotihuacan’s Retail Edition is Still Glorious

Despite my anger over the fact that Board&Dice games never have an insert, it’s clear that Board&Dice has their focus on the right area: solid gameplay and exceptional components.

Board&Dice sent me a retail copy of Teotihuacan for this review, and everyone who tried the game said roughly the same thing: “these pyramid pieces feel deluxe.” Even now, seven years later, Teotihuacan feels like a deluxe Kickstarter edition. The wooden components could, and probably should, be smaller, but the chunky bits still work, especially the gold resources that stand out across a table (and serve as a reminder that your neighbor Wil is probably about to purchase a decoration tile on his next turn).

I really love the way the board’s eight location spaces are right-side-up only to a person sitting opposite that portion of the main board. In that way, the rondel runs in a circle, and since there is no reading required, it’s totally fine to be sitting “upside down” from a space across the board. The rulebook is dense, but the section headers are easy to navigate, so whenever I had minor clarifications to seek out, that only took a moment. Better still? Teotihuacan has both first-time setup and standard setup variations to get new players into the action more quickly.

It will sound strange to say this—especially as a deluxe player board junkie—but I really appreciate the fact that Teotihuacan does NOT have player boards. There’s not much in-game information that needs tracking, and once a player begins unlocking personal technologies, it feels like everyone always remembers the sweet extras they earned during play. Each player has a small tile used to track resources above five—in this way, you get fewer wooden components in the box, which I am guessing lowered the retail price point, and the dice are slightly-larger-than-usual six-sided dice that make it easy to tell from afar what strength each worker possesses for their actions.

Teotihuacan Still Has That Tension

“[profanity deleted]!” a player would say to start their turn. “I need more cocoa, but the action I really want won’t cost me any cocoa if I take it now!’

For the majority of my turns, even when I had a plan of something I wanted to knock out to align with my strategy, I was surprised how often I was cursing the choice I was about to make. Teotihuacan holds up because that tension is lurking nearby on almost every turn.

Part of that tension is the game clock. Teotihuacan’s Eclipse structure is tied to the advancement of a small white cylinder up a track. When it reaches a black cylinder, the era is over. Normally, the white cylinder goes up once each time all players have taken a turn. But it also goes up each time a player ages one of their workers from a five-pip die to a six-pip die, forcing that die into Ascension so that it becomes a one-pip die again for future turns.

That sometimes means that you think the round will end in three full turns per player—and then two of those players ascend a die, and the last player of the round finishes their turn. Rur-roh! In addition to those timing considerations, each Eclipse era lasts (at least) one round fewer than the previous one. I love the way players hear the clock ticking in games of Teotihuacan.

It All Still Works

Getting Teotihuacan: City of Gods back to the table made me realize how important it has been to my play habits to go back in time and revisit titles from the recent past. Many of those who follow my content know that I like to whip out old games from time to time, and this journey to complete our coverage of the BGG 500 has been a delight to see how many great games are still available at retail that are not the newest, shiniest object.

Teotihuacan works because its rondel and worker placement mechanics still shine. I play a lot of games that my review group would call “overproduced”, where it was clear that the toy factor was more important to the people involved than a game’s design. Teotihuacan aligns its incredibly simple action system with a production that matches, but doesn’t try to exceed, its goal to bring great gameplay to the table at a reasonable price point.

The biggest surprise during my review plays? The playtime is less than I remember during that first play pre-COVID. Three-player games of Teotihuacan, even with new players, took about two hours, less when players knew their way around the game. (I did not play Teotihuacan solo, despite the included solo mode designed by Dávid Turczi.)

For a game with this level of strategic planning, that’s great news, especially because many of the turns are very fast. Downtime with three players is very low; the one exception to that came any time a player had to build either a pyramid piece or a decoration and needed to puzzle out where to place a tile to get track bonuses.

The main nitpick I have with Teotihuacan is tied to player count: I think Teotihuacan is a four-player-only game. Sure, you can play it with fewer, but all four player colors are always in play to ensure there are enough dice situated around the board so that cocoa income (or cocoa costs, depending on your viewpoint) can remain high. With four players, the eight locations are more dynamic and force players into tougher decisions as they math out where they can place their workers for lower costs.

That’s not necessarily an issue—like my favorite Euro from 2024, Shackleton Base: A Journey to the Moon, I simply will choose Teotihuacan to table only when I have a full player count. I really enjoyed my plays at three, but I had less fun with my two-player review play. Because the downtime is minimal, four players here won’t be a major concern.

Teotihuacan: City of Gods is my second-favorite Tascini design; Tiletum’s standing in my collection is safe. The state of the tabletop industry has many of my friends seeking out classic Euro designs that stand the test of time; if that describes you, I highly recommend adding Teotihuacan to your collection.