Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

“Why haven’t I heard anything about this game?”

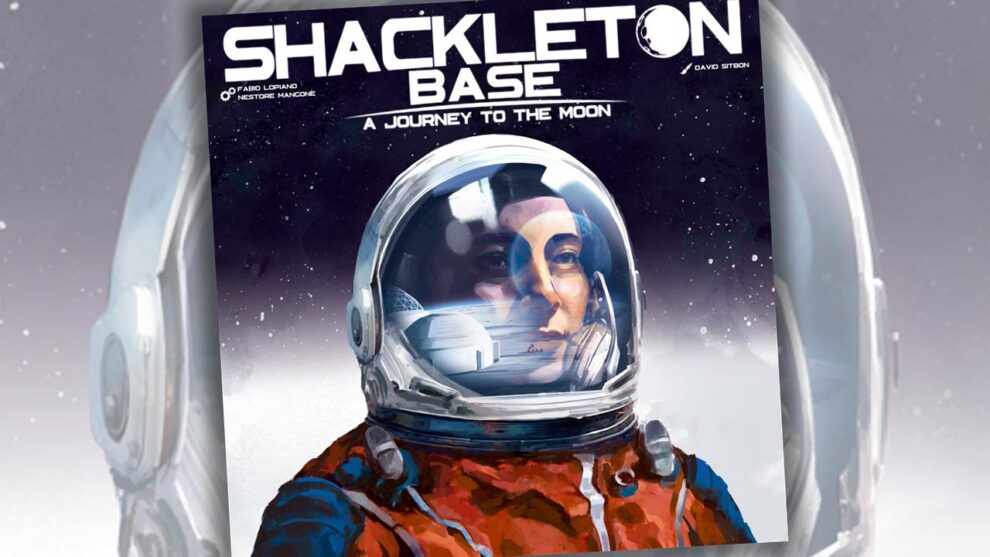

I had just finished my second game of Shackleton Base: A Journey to the Moon (2024, Sorry We Are French), but it was the first play for the guys in my review crew. We had a lengthy post-game discussion that started with the thoughts of my buddy Eric, who marveled at the quality of the design and the interesting choices all of us got to make during the course of our 18-turns-per-player experience.

I had a good feeling about Shackleton Base when I met with one of the game’s designers, Fabio Lopiano, at the Festival International des Jeux back in February 2024. Fabio was leading a demo of Shackleton Base when I had a meeting with the Sorry We Are French marketing team at the show.

Fabio and I talked for about 20 minutes, mostly about Shackleton Base but also about the game Autobahn; both were games co-designed by Fabio as well as Nestore Mangone (Darwin’s Journey, Newton). Despite some very fiddly components, I was really impressed by the gameplay of Autobahn and particularly the way scoring was executed with its focus on ladder-climbing executives moving into higher positions within a corporation by the end of play.

My sticking point with Autobahn was the sheer number of mechanics thrown into the mix alongside a series of edge-case rules that required a certain kind of Eurogame lover to enjoy. A scattershot rulebook didn’t help the cause. The core ideas of Autobahn were lovely, but the execution was a little bumpy.

Shackleton Base takes a different approach, thanks to a series of rules that are so streamlined that I taught my first multiplayer game in about 25 minutes. (My review copy arrived before there was a rules video or a robust rules forum on BGG.) So, the first positive for Shackleton Base came through right away: the rules are pretty straightforward for a medium-weight Euro.

The second positive came when I tried out the solo mode, and the simple AI deck mixed with a fairly streamlined ruleset for the automa made administration easy. I liked the solo mode but didn’t love it, in part because I thought there wasn’t enough tension in the main part of the game’s moon map.

After trying the solo mode, I did a three-player game with other human opponents…and the skies opened up. There’s something really good here, I thought about halfway through the game. By the time we wrapped up, all three of us expressed the same thoughts: Shackleton Base is somewhere between really good and truly great.

Lunar Landing

Shackleton Base is a 1-4 player worker placement and area majority game that asks players to help build a base on the real-world Shackleton crater on the lunar south pole of the Earth’s moon. Each player’s “space agency” is really just a choice of player color, with three additional Corporations available to help players build out their portion of the base.

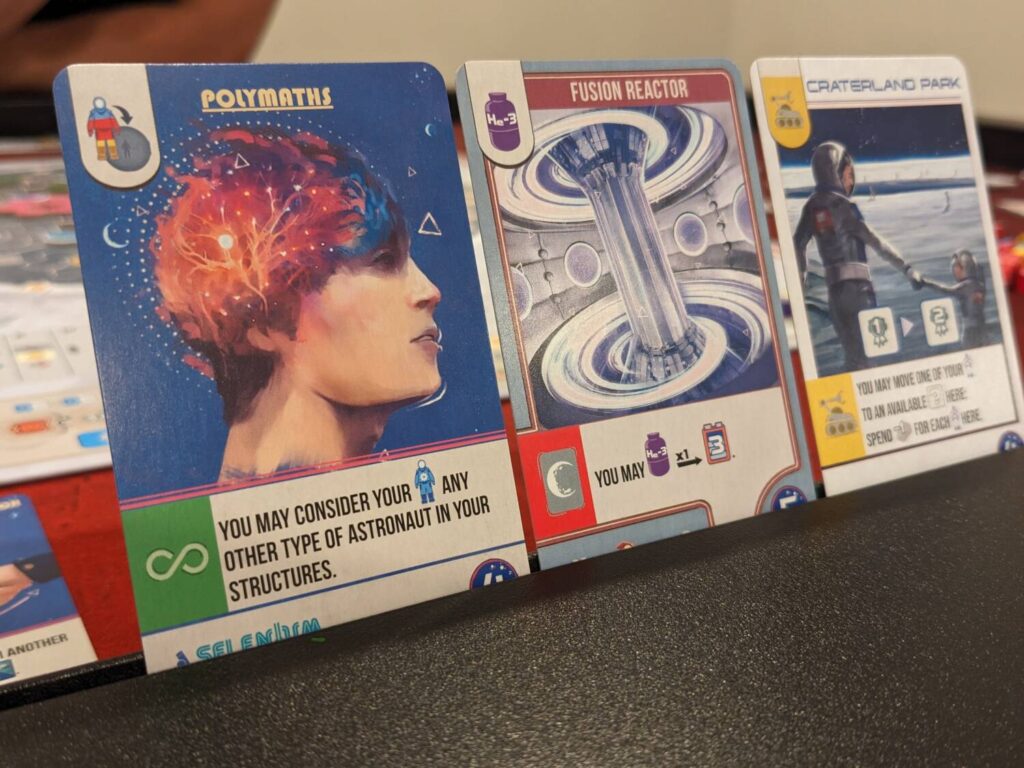

These Corporations change Shackleton Base in ways I didn’t understand when I first watched Fabio lead that demo in France. That’s because the Corporations require players to interact with the core gameplay in varied ways. Regardless of player count, three different Corporations are featured in each game, from a pool of seven Corporations included in the box. Players can collectively choose to make the game fairly vanilla or a lot more complex thanks to complexity ratings included for each of the seven Corporations.

Beyond the Corporations, Shackleton Base is mostly a worker placement game, with workers selected using a fun administration phase that begins each of the game’s three rounds. These workers come in three flavors: yellow (Engineers), red (Technicians), and blue (Scientists). Each of the round’s shuttle tiles—equal to the number of players plus one—display six workers, with differing combinations of the three available worker types, as well as an allotment of certain resources. There’s also a number at the top of each shuttle that will dictate turn order for the current round.

This gives players a chance to pick their strategy for the round based on the types of workers they bring into their play area, and whoever picks the lowest-numbered shuttle tile will go first, with turn order assigned in ascending shuttle tile order. Then players take six turns, one worker placement at a time, until the end of the round when an administration step cleans up the board and provides income for each player before maintenance costs are levied.

The meat of the game, the Action phase, is a blast in Shackleton Base. Players must place a worker in one of three action areas. The first action area choice is called “Exploit the Crater” (yes, like the game’s less-than-ideal title, even the action titles struggle to roll off the tongue), and I was surprised how interesting this mechanic was with larger player counts. Basically, a player can place a worker in a space facing one of the rows on the map to trigger an action based on the presence of any active and powered structures in each hex of that row.

Exploiting the crater gives the active player resources (titanium or “rare earth”), cash, or Corporation resources that are used when taking applicable actions later. But taking this action requires the activation of every powered hex in that row, which might cost money—if a player does not have a presence in a hex, they have to pay the player who has the largest structure in each hex a small fee to activate the tile. This action also makes the placed worker available for an area majority mechanic that gets resolved during the administration phase.

At the end of the round, the player who has the largest amount of structural real estate in a row with a worker takes the worker onto their base (player board), which will later trigger a series of income, one-time bonuses, end-of-round administration, and/or victory point bonuses.

I love the puzzle of trying to determine where to place new buildings in the crater to give myself a chance to secure more workers. Better still, these considerations can be made without slowing the game down because a thoughtful player can use their downtime to plan ahead.

The second action area has usually seen the most attention in my plays: the Command action board. This is where players can build structures from their base (player mat) onto the crater map, take three Corporation actions, or “fund projects”, the game’s way for players to spend resources to build Corporation cards into their tableau.

The Command board provides the ultimate in flexibility, but it always seems to make players push hard to align with the game’s hook: any color of worker can be placed on any space on the Command board, but if a player matches the appropriate worker color with the aligned action, they get a small-but-meaningful bonus. For example, if a player sends a yellow worker to build a structure, they get to end their turn by taking a Corporation bonus from one of the spaces adjacent to the newly-built structure.

And the earlier a player takes an action on the Command board, the cheaper it will be, so going to an action space early with the right color worker is a huge benefit to the player going first in a round. (Across my three plays, particularly in my four-player game, I found turn order to be pretty important.)

The Command board, like most everything else in Shackleton Base, reminded me a lot of the game Tiletum but for vastly different reasons. There’s nothing strikingly original in Shackleton Base, much like Tiletum, but I was shocked at how well everything clicked during my plays of both games. There are fun decisions to make every turn, there’s tension aligned with mathing out the right moves at the right time, and scores might pile up but this is definitely not a point salad. Everything feels earned, and having the right overall strategy mixed with making the best round-to-round decisions gives the game a nice balance.

The Command board features something else that I love in worker placement games: strict limitations on the best possible actions and costs. Depending on player count, only a certain number of buildings can be built in a round. And the cost really spikes if a player decides to send a worker to the building action late in a round, driving the feelings of impending doom down to all players. It was always fun to see a “gold rush” of activity around a certain action when only a spot or two were left for an action, with players cursing as they paid four or five bucks to take an action out of fear that they might get closed out of an opportunity during a round.

The game’s third action, Visit the Lunar Gateway, at first feels like the terrible “I’m essentially passing” action in other Euros (take one coin, waste a turn to become first player in the next round, etc.). But this action slowly revealed itself to be vital when you need to fill your base with the right color meeples to trigger maintenance phase bonuses and get a slight boost of cash to take a more optimal turn later. In the third and final round of Shackleton Base, I found myself taking the Visit action more frequently when I could maximize my end-game score…and in my four-player game, multiple players used this action as their final action of the game for precisely this reason.

Despite my initial fears that 18 turns per player would take an eternity, my plays turned out to be much faster than I had guessed. That’s because many turns of Shackleton Base are quick—Exploit the Crater and produce resources, or maybe do the same action to grab money instead of resources. Even placements on the Perform Corporation Actions line are quick from time to time—grabbing resources, bumping my reputation (a track that yields end-game points as well as in-game bonus options), then fulfilling an order on a Corporation board.

Games of Shackleton Base wrapped up in about 30 minutes per player. For the amount of action in the game, this is great news.

The Corporations

The game’s seven Corporations range from vanilla ice cream (Moon Mining, Artemis Tours) to more complex entities. No matter which three Corporations are in the game, players will have an opportunity to place blue scientist meeples to Exploit the Crater for Corporation token bonuses, then use those bonuses for a mix of recipe fulfillment, increased resource production, or more advanced actions if Corporations such as To Mars or Sky Watch are in play.

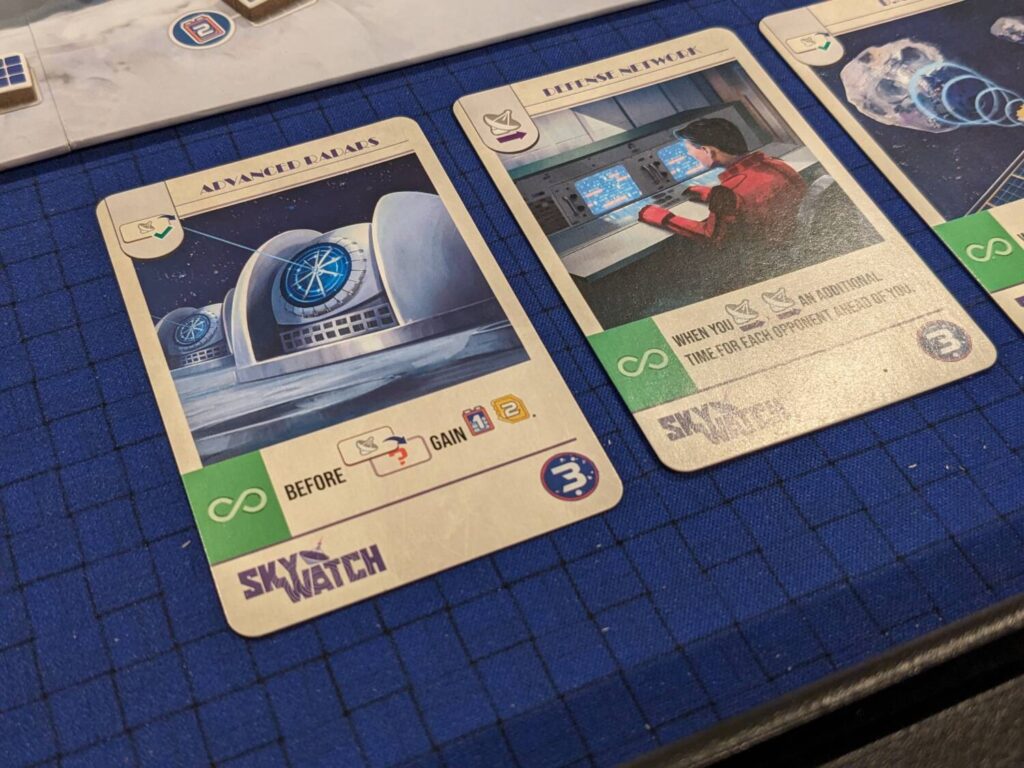

Some of the more complex Corporations are crazy. Sky Watch penalizes all players if a “Defense Program” is not completed by the end of the game, by destroying buildings (and producing negative victory points for building owners) that are within a certain zone of the map where a meteor will strike if it isn’t shot down by the “Star Wars”-style space defense initiative.

We used Sky Watch for our four-player game and it was a fun game of chicken as players had to work together to place defense markers on the board to ensure that a section where two of the game’s four players had a majority of their buildings didn’t get messy. That forced some players to interact with Sky Watch more than others, but there were rewards available for anyone who spent time investing in that Corporation.

The Corporations expand the number of things players have to worry about, which can in turn make Shackleton Base a slightly heavier game if more complex companies are chosen. There are resources to manage, a card market for each Corporation that will score end-game points as well as additional victory point boosts, ongoing or one-time powers, and immediate resource bonuses. Each player has one goal token they can use when they achieve certain conditions within each Corporation, but timing when to claim these goals makes everything in the game a race. Players can also take a single bonus Corporation action in a couple different action areas that might give them a chance to squeeze ahead of unsuspecting opponents for a particular goal.

The Corporations are dope. Their difficulty can be managed based on player experience before each game, which I love. (For new players, I would stick with the Corporations recommended in the rulebook.) The Corporations give each game a slightly different look, extending the game’s variability well beyond my review plays. (I haven’t even used To Mars, the game’s most complex Corporation, but it looks like something I will include for my future plays with anyone who already knows the core game.)

Best of all, the action on the main board (separate from the three Corporation boards living nearby) is enough to keep the decision space interesting from game to game.

Like a Good Euro? Get Back to Base

Shackleton Base: A Journey to the Moon is a big surprise—a game that was only on my radar thanks to my time in France that has now become one of my five favorite games of 2024.

Shackleton Base is the second-best pure Euro I’ve played this year, with one major edge over the game in the top slot, Inventions: Evolution of Ideas—Shackleton Base is significantly easier to teach and plays in about two hours, things that Inventions can’t claim.

Beyond the game’s title (there’s no getting around it, Shackleton Base: A Journey to the Moon just isn’t sexy), the rulebook could use some localization work around the edges, at least in English. Plus, some of the game’s rules edge cases—do funded project card powers become available right away, like reputation upgrades?—will work themselves out as the game’s forums come alive, but the layout of the rulebook doesn’t always make finding answers to these questions easy.

One thing I thought the rulebook did quite well, though—the frequency and the detail of the pictured examples of certain processes in action. The best example of this was the walkthrough of an astronaut retrieval during the second step of the maintenance phase. That one made clear what was meant by the “total structure size” of the area majority leader when measuring which player would earn an astronaut pointing at a row on the main crater map.

The iconography and graphic design on display here is “fantastique”, designed by Ulric Maes and the Sorry We Are French in-house artist David Sitbon (once again fantastic, as was his previous work for Zhanguo: The First Empire and Galileo Project). I was surprised how often new players were able to locate the areas where they could find out what cards did based on the icons listed on their player mats, the main board, project cards, and Corporation tokens. Looking for the little wrench told players what their administration costs would be. The symbol for taking astronauts from the Lunar Gateway is consistent and clear.

Quality-of-life superlatives continue with the tuckboxes included for storage of the game’s many components as well as the double-sided player aids used for each Corporation’s actions and project cards. While it is impossible to tell what players have which powers at all times from across the table, I was surprised how little that mattered during play, in part because of the more Euro-centric nature of play (a decreased level of interaction) and because the number I needed to see most—the value of each opponent’s cards in total victory points—was easy to pick out.

As a production, Shackleton Base is a home run over the fiddly nature of Autobahn. Save for the lack of a player aid detailing actions in plain English (or your local language of choice) and for a moment where someone knocked over a meeple on the Command board, which made other meeples in other nearby spaces fall over in a Dominoes-style cascade, Shackleton Base should not offend the majority of players.

The line between a 4.5 and a 5.0 perfect score? A few items, starting with player count.

I enjoyed my play at three players, but I think the game shines brightest at four players. There’s more action on the crater map, there will be more chances to earn astronauts during the retrieval step, there’s a massive fight on the Command board for spaces, and at one point we ran out of astronauts in the Lunar Gateway area. I loved all that came with this level of tension, and some of that tension was missing during my solo play (which, again, simulates a normal two-player game).

I would not buy this for the solo mode, nor would I buy this in the hopes that it would land well with a two-player only environment.

The second are the “Agency Leaders”, each player’s personal ongoing power ability. Simply put, these are not game-breaking enough to be interesting. One of the powers grants a player a one-dollar (technically, credits) discount when taking the “Fund a Project” (build a card) action. This ability, like all the game’s abilities, gets better once a player builds their size-six structure known as the Laboratory onto the map, but we found that it usually takes at least a full round, maybe two, to gather the resources required to build that massive building.

In terms of game-breaking player powers, this is certainly not a standout like Marco Polo II: In the Service of the Khan. Those looking for real asymmetry with their player powers should look elsewhere, but if you are going to lean into the powers, try the “B” side of each Agency Leader ability because the “A” sides are a miss.

Money feels a little loose, but I have a feeling that this is intentional, based on my experience with Autobahn, Lopiano and Mangone’s previous design. By the third round of Shackleton Base, it felt like all players either had enough money to not take a money-driven action (thanks to previous income, project card abilities, etc.) or they could find a place on the map to drop a red astronaut to earn nine or 12 credits. I wish money was just a tad tighter, because I think that would have made the final round of my plays a bit more dramatic.

The last point is a tricky one, because I can’t tell if I’m doing something wrong or if I just haven’t played the game optimally yet. The game includes scoring tokens for players as they lap the track, which ends at 50 points. These tokens imply that scores might reach a high of 200-250 points…yet, the highest score I have seen in a game so far topped out at about 125 points. I have no idea who is going to be able to score 230 points in a game like this, and neither did any of my five unique opponents who joined me for my plays.

Otherwise, Shackleton Base: A Journey to the Moon is an absolute must for fans of medium-weight worker placement games, particularly at the maximum player count. The playground on display here is ripe for expansion content in the form of additional Corporations and player powers, so I’m curious to see how well this sells in the hopes that we can achieve those dreams. Sorry We Are French has figured out the medium-to-heavy strategy game space; between Galileo Project, Zhanguo: The First Empire, and IKI, SWAF keeps rolling out a new banger every year.

Give this a look when it releases at SPIEL 2024!

Add Comment