Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Unfortunately for Mindclash Games, they have made some of the best games I’ve ever played.

Let me explain. I’m a big fan of the films directed by British Oscar-winning auteur Christopher Nolan. I’ve been onboard since his first film, Following, and then the bigger splash he made with his second release, Memento. Nolan has certainly gone mainstream since then, with The Dark Knight trilogy of Batman films, Dunkirk, and last year’s award-winning masterpiece, Oppenheimer.

But do you remember Insomnia, back in 2002? I do. Nolan did a lot of press for the film, so I had the chance to see Insomnia at a screening in San Francisco where the director did a Q&A afterwards. The film was only OK. One could tell from the audience’s reaction that, well, Insomnia was no Memento.

I thought back to my experience with Insomnia while doing my three review plays of the game Septima (2023, Mindclash Games). Ultimately, particularly after my second play—a four-player game of the “full” version of the game, after a four-player game of the “basic” game—I realized that I’ve set my Mindclash expectations too high.

Septima is fine, maybe even better than average. Its main issues are not really issues at all, mechanically speaking. It’s wild to run a witch coven, trying to heal patients in a fantasy world where you’re being chased by witch hunters. Attempting to become the next “Septima” (the chief witch position of the game’s fantasy setting) while trying to keep your witches from being exiled by angry citizens in court is quite a concept.

If another publisher—maybe any other publisher—had released this game, I think I’d like it more. But when you’ve created Voidfall, Anachrony, and Trickerion: Legends of Illusion, the bar for a player is a little higher.

My Witch is on Trial!!

Septima is a 1-4 player hand management game that supposedly plays in about 25 minutes per player. I’ll take the high road here and say that the game takes a bit longer than that to play.

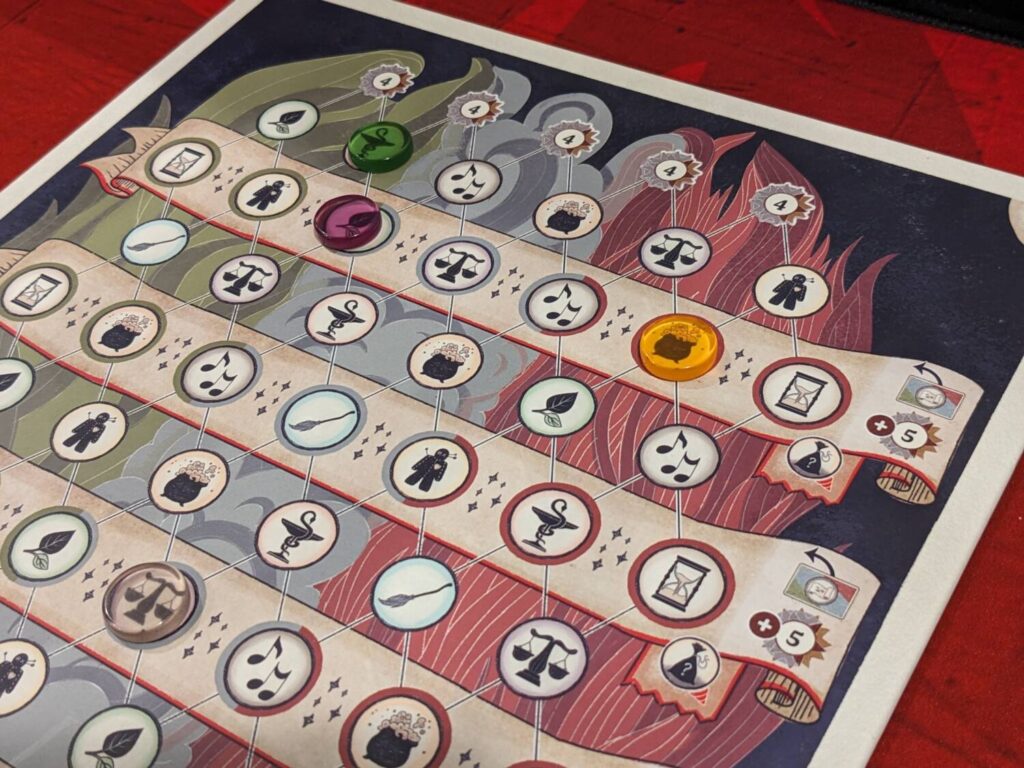

Running a witch coven in the imaginary town of Noctenburg is no easy task. Players, navigating town using a meeple token representing the coven’s leader, must outscore opponents by collecting ingredients to brew potions, learning spells, healing patients, pleading with the locals to add members of their loyal citizenry to court proceedings, and occasionally chanting to keep suspicion below an acceptable threshold.

Yes, singing is an integral part of the game.

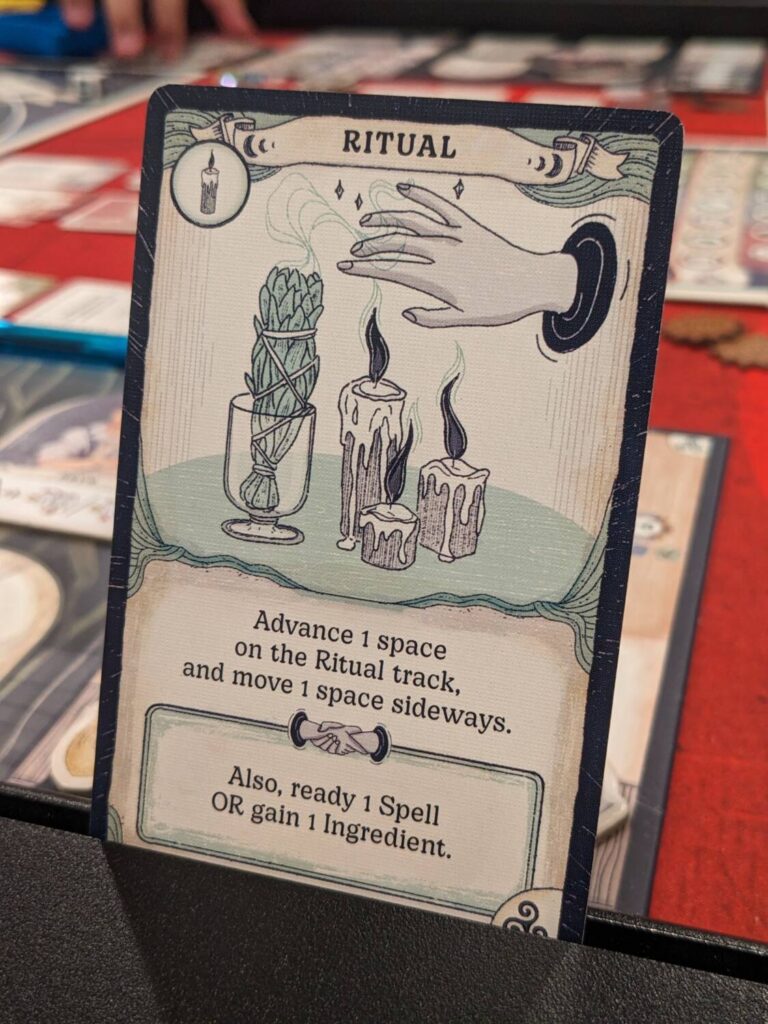

Septima has quite a bit more going on than that, but that’s a broad overview. Everything in the game is managed with a hand of nine action cards—all players have the same nine cards, strikingly similar to another game with a nine-card hand—and much of Septima’s action selection system is tied to matching the chosen action card of at least one other player or the Septima character running things in Noctenburg. The Septima’s actions, dictated by a randomly-drawn token sitting in the middle-bottom portion of the board, allow players to match with the Septima at a slightly higher cost to their reputation in the neighborhood, represented by a suspicion track referenced earlier.

Matched actions are a little more powerful than a card’s base action, so matching is situationally a good idea. But raise suspicion too much, and the locals start to catch on…in a bad way. Managing this tension is my favorite part of the game.

Septima is played across four seasons, with five turns in each season. That’s 20 turns…and, I am having a hard time imagining any scenario where those 20 turns can wrap up in about 100 minutes. My four-player games took 2.5 hours (the basic game) and almost 3.5 hours (the full game). In the full game, two of us had played the basic game at least once, so I think for four new players trying the full game, you are looking at a long sit.

But I really don’t have an issue with the game length of Septima. Mindclash Games doesn’t make one-hour Euros (mostly true). My issues come down to a number of minor points that really blunt the impact Septima should make on its audience.

Oh, That Upkeep!

For a game that is so easy to set up, Septima has a frightening array of upkeep steps during the game, particularly in rounds where any player raises their suspicion level.

Some of these steps are simple; moving the round marker is easy. But after each player takes their turn, someone has to update the turn marker in that round. This is vital, because Septima makes things tricky when it comes to ingredient collection (those potions needed to heal the locals require very specific things from the forest surrounding the town on the map). During a Collect action, players can only access the two ingredients adjacent to the current turn in a round, as well as any crystals (wild ingredient tokens) adjacent to the hex where a player’s leader token is standing.

All good. Someone must also update the triangular action step marker for each turn, which has five steps. That means that someone is moving another token a few times (five) every turn.

Oh boy.

Healed patients need to be removed after each turn. New patients have to be added each round. Patients from previous rounds need an angry citizen added to the board. Witch hunters are chasing coven leaders if they raise suspicion, and those hunters have to be managed individually every turn, as many as four times per turn. But those hunters have rules, and if a hunter couldn’t chase a witch leader in a round, someone has to move one into that player’s zone. Spells have to be wiped from a ritual track at the end of each round.

One player said this after our first play, and I echo the sentiment now that I’m three plays in: there’s a ton of flow-killing administration in Septima. I guess the design needs all this upkeep to function, but it’s a pain to manage it all, particularly if you are the person teaching Septima to a new group and take on the responsibility of doing this upkeep during and between 20 rounds. That’s a lot of things to do while, you know, thinking about your own actions!

Moving beyond the upkeep, there are a few other things that rustle the feathers. As a coven leader, one of the main ways of scoring points is adding witches to your player board. Witches provide ongoing effects, but also trigger scoring on a “Book of Divinations” card dealt to each player during setup. Essentially a Euro-style list of personal milestones, the Book card has four lines that can score. Witches under your control at the end of the game make you eligible to score one line each from the card. Have four witches? You’ll score everything on the Book card, as long as you meet the line’s requirements, such as ending the game with a certain number of leftover potions or ingredients.

You begin the game with two witches. Getting a third witch is tough, but can be done if you advance to the top of at least one of the three ‘patient tracks’ on your player board. (We didn’t play a single game where someone topped two tracks, so I think my initial assumption was right: maxing two tracks in Septima is really tough.) Getting witches from other sources is extremely limited—once per season (five turns), a random witch from the supply goes up for auction, an auction in Septima that is called a trial.

The trial/auction mechanic was ultimately a disappointment in my plays. During each season, players add meeples, known as loyal citizens, to the ‘Crowd’, an area outside of the local courthouse. Sometimes, players can add these meeples directly to a trial chamber to get a leg-up on voting later. When the trials begin, all citizens in the crowd are added to a number of angry meeples—red tokens representing those who don’t believe in those witchfolk—then placed in a draw bag and shuffled up.

If angry citizens outnumber or tie drawn loyal meeples of any player color, the witch on trial is exiled (and kudos to the design team for not drawing a darker conclusion to the end of a trial). If player-owned citizen meeples outpace angry citizens, the individual player with the most drawn loyal citizens wins—which earns three points and the witch that was on trial.

Only a small number of meeples are drawn each turn, and while having a meeple majority makes sense on paper, it was shocking to see how often the player with the most citizens in the draw bag lost the trial. In our first game, I had the meeple majority for all eight of the game’s trials: the four trials guaranteed to happen each round, and the four extra trials that took place thanks to having other player witches captured by hunters, putting them up for bid for all players during the trial phase.

I lost all eight trials. As the losses piled up, I was just howling with laughter, spiced with a healthy dose of anger. In a couple cases, it made sense—there were more angry meeples than total player meeples in the bag. But for the last two trials, I maxed out the number of loyal citizens who could compete for more witches and lost witches to players who had less meeples in the crowd.

As a strategy gamer, you expect that a strategy game will have certain elements. If I have the most military power in a fight, I should win that fight almost every time. If I have an area majority in a game like Pax Pamir 2E or El Grande, I expect to outscore opponents who do not have a majority. In Septima, if you have the best odds at winning a trial, it’s a total crapshoot knowing if you will win or not. This had a huge effect on end-game scoring.

So, in a game about witches, witches are tough to acquire. The real shame there is that you want more witches because you want more powers, and Septima doesn’t have much in the way of engine-building. You will not be better at most of the game’s actions by the end of play, meaning that your playloop is mostly the same all game long. Gather ingredients, brew potions, walk to patients, heal patients, lower suspicion (usually through the Chant action) to make sure you stay out of the witch hunter line of fire.

Where’s the Exhilaration?

In terms of mechanics, the hand management and action selection portion of the game—phase A of the five main phases—really delivers. Beyond the gameplay, Septima shines in the area that Mindclash always delivers on: this is likely the best-looking production I’m going to see all year, likely only to be outpaced by other new Mindclash productions.

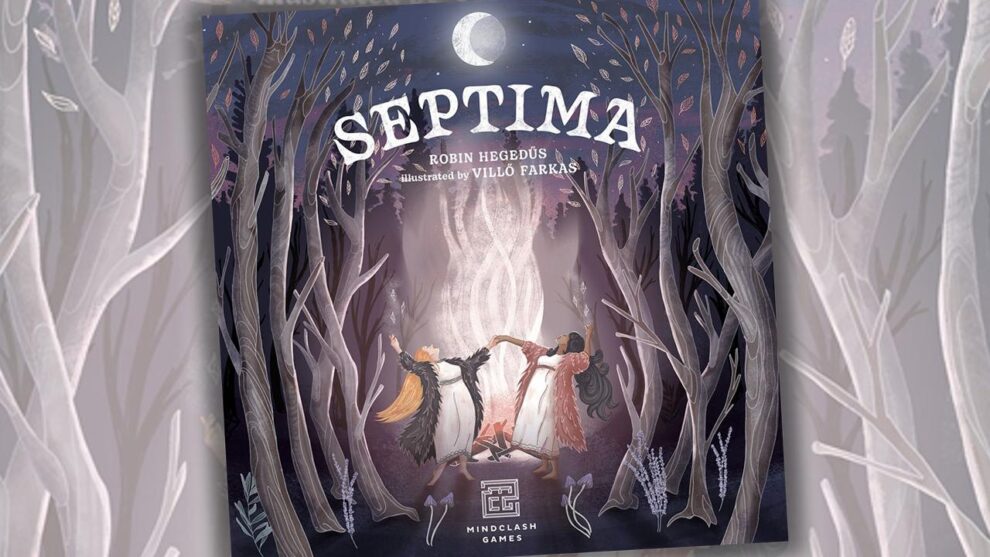

I’ll start with the artwork by longtime Mindclash contributor Villȍ Farkas, who has provided art for almost every other Mindclash design. I love her illustrations on the witch tiles, the Septima portrait on the board, the box cover, the player cards, the solo cards…you name it. All of it is gorgeous. I particularly appreciated the level of diversity in the witches of the game’s supply, including the age diversity. You’ve got witches of all shapes and sizes to choose from, and it’s a joy to look at them.

(One negative about the witch tiles: while the rest of the game smartly skips the use of icons to describe what everything can do—such as the main hand cards, the spells, and the player aids—the witch tiles use no words, leaving icons that appear only on the witches. All game long, people will be looking for references on what each witch can do. That one was a miss!)

The player boards are mostly clean, with an easy-to-read suspicion track lining the left side of each player board, space for witch tokens, a holding area for potions and ingredients, and the patient tracks with mostly clear ways to track what kinds of bonuses will be earned by moving up each column.

We originally had complaints about the board’s six zones, which separate where witch hunters will pursue other leader tokens, but those issues went away by our second play. The rulebook is not the best work I’ve seen from my favorite proofreading team, but the index on the back inside cover got most of my questions answered quickly. My main rulebook issue was not the clarity of describing how the game works, but where questions would be answered. This issue also went away for us during the second play.

The theme here is fantastic, and you probably aren’t playing any witch games quite like this one. I like that I can fly sometimes. I like that I can pull a fast one on the people by singing my way out of trouble. The whole thing feels folksy, in a good way.

The only production issue that I consider a negative: Septima needs a better insert. Or any insert. Or a bigger box. My last Mindclash game was Voidfall, which included the single-best storage solution I’ve ever seen. Septima…is not Voidfall, certainly not in regards to storage. At the time of this writing, I still haven’t figured out a way to get everything back in the box and have it seal shut. The box top is teetering on top of a mountain of chits, player boards, scoring pads, and other gear, and that’s before opening the expansion content Mindclash sent with the game.

This One’s Witchy

On the one hand, Septima is a fine game. I consider myself a Mindclash junkie, so I needed to know how this one would play, and it plays OK. There’s too much upkeep, but the core game mechanisms—choosing which card to play, negotiating with other players in the hopes of swaying someone else to take my card action, and saying witch things to opponents to stay on brand—are great, and should shine brightly in the hands of the right player group.

On the other hand, Mindclash gave us Trickerion: Legends of Illusions. Anachrony is a top 100 game on BGG. I played Voidfall 14 times last year, so it did something right! I know what great looks like, because Mindclash has delivered greatness quite a few times. If I’m going to take 3-4 hours to set up, play, and tear down a Mindclash game, I have other options that just work better than Septima.

For the game’s strategic weight, Septima is not worth the squeeze compared to other items in the Mindclash catalog. As a starter, midweight Mindclash game, though? Septima is fantastic. It shows players what the Mindclash best-in-class approach to worldbuilding looks like, it highlights their strong focus on production, and the rules overhead is light compared to megabeasts like Trickerion or Voidfall. Plus, it comes in at a price point I found to be very reasonable: an MSRP of $65. That is more than fair for a game that has two main play modes plus a solo mode.

Speaking of play modes: the official teach video for Septima uses the basic game format, but I only recommend basic for gamers newer to the hobby. I think those looking for the full Septima experience, particularly the use of Spell cards that give players juicy one-time or ongoing powers, powers that can be reset by taking certain game actions, should stick with the full game. That did add an hour to my playtime, but I thought the full mode made everything a little more interesting.

Solo was OK, but I would not recommend buying Septima only for the solo. Designed by David Turczi, Septima’s solo AI does a few things that just don’t happen in the base game—certainly not at the speed they would with human players—and the solo serves as another reminder that a negotiation game needs more human players to function correctly. The lack of negotiation at lower player counts means I never tried Septima at two players, so go with a higher player count.

Septima. Good, but not peak Mindclash. I will get the expansion, Septima: Shapeshifting and Omens, to the table in the months ahead for a separate review in our Quick Peaks series.

Septima was my first foray into the Mindclash world. I backed the deluxe edition on KS and the production is top notch. I’ve only had one game so far at 4 players and we were learning as we go. That was a rough time. I don’t think we got all the rules correct until the end of the game and even then we found a rule or two we had been doing wrong the whole time. Mostly my fault as I was the “teacher”, but I prefaced it by saying I only sort of knew how to play.

Witch hunter movement was weird, witches were hard to obtain and/or keep, loyal citizens didn’t seem to make much of a difference unless you could put them directly into the trial spaces, and everyone seemed to just hang around the middle of the board trying to heal patients first. Once the patients got healed, it was more like “guess I’ll just collect some stuff” or “I’ll move further away from the witch hunter.”

The whole experience was lackluster to me. The initial game description and seeing how the action selection worked with the cards was intriguing when I was learning it. But after suffering through a 4 player game of it, I just don’t feel myself wanting to go back to it. However, it does make me want to try Anachrony or Trickerion instead.