Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

About two years ago, I picked up a copy of Beowulf: The Legend on the secondary market. I was in the waning days of my Knizia Era, still eager to try any and every title I’d heard mentioned in the context of his best work. Beowulf was one of the more obscure titles on the list, a long-out-of-print Fantasy Flight production with artwork from John Howe and one of the ugliest boards I’ve ever seen.

It took me almost a year to get anyone to play the thing. I would beg and plead, prompt and cajole, but people would take one look at the box, or the board, or the manual, and run in the opposite direction. It has been my job to recommend games once a week to a gaming group for the past three years. I am used to being trusted. This and Taj Mahal, man.

When I finally got a group to the table, once we’d struggled through the manual and stumbled through the first few auctions, I was entirely vindicated. Beowulf: The Legend was such a smashing success, our cheers and barbaric yawps so loud, that people came in from the next room to see what was going on. Those who’d poo-pooed came to regret their decisions, sheepishly asking if they might be able to play the next week. Ever gracious in victory, I said, “Of course.”

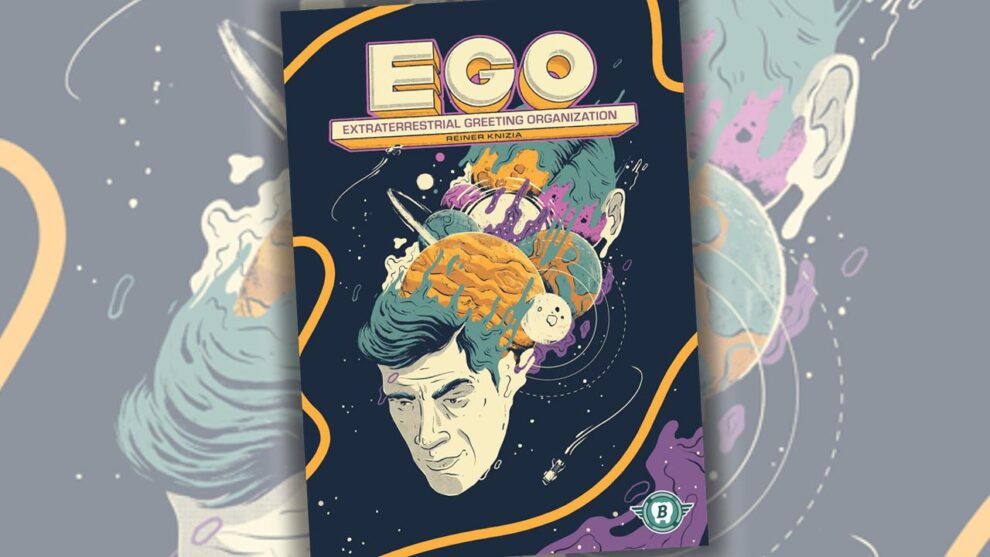

Fast forward to the present day, and Bitewing Games has seen fit to republish Beowulf: The Legend as EGO, one of a trio of space-set Knizia games they released in 2025. I’m in favor of all the changes. I am not precious about these things. Beowulf’s idiosyncratic L-shaped board is swapped out for a series of modular boards. The heinously ugly graphics and icons of the original—love them though I do—are replaced with actual graphic design. And changing the setting is a perfectly reasonable thing to do; Beowulf: The Legend was never a narratively evocative experience.

I sat down with a group of my most trusted advisors for a game of EGO. Most of them—all of them?—had not yet played Beowulf. We set up the game. We read through the much-improved manual. The game started. Within fifteen minutes, we were all unhappy, and not in the fun way. I was stymied. Puzzled. Morose, even.

Space Risk It for the Space Biscuit

Within the narrative of EGO, you’re diplomats doing your best to represent your respective peoples through a series of Negotiation and Bidding Events across five different Systems. As players, this means you participate in a series of auctions. Most of the auctions are paid for using cards from your hand, which are decorated with one of five symbols: Gifts, Persuasion, Intrigue, Tech Trade, or Charisma, a wild suit. The auctions come in two flavors: constant upward bidding (Negotiation), and simultaneous reveal (Bidding).

In both cases, you are bidding for first right of selection from the wheel o’ prizes for that particular event. First place may be points, or money, or a powerful card you can use later. Last place is likely to be Offense Tokens, which have a compounding negative impact on your score. The fewer of them you have come the end of the game, the better. Surrounding these auctions are smaller Events, which allow you to gain cards, shed Offense Tokens, and so on.

Despite these aucti-o-matic trappings, EGO, like Beowulf: The Legend, gets all of its juice as a push-your-luck game. During Negotiation Events, in which players take turns playing one or two cards to the table at a time, you can choose to start your turn by taking a Risk. The broad strokes of this process are identical across both games: You reveal two cards off the top of the deck and add any applicable symbols to your total.

Risks are the masterstroke of this design. A player who should have been out of the auction rounds and rounds ago can hold on if fortune is on their side. It turns what would otherwise be fairly dry auctions, near-perfect calculations of cost and reward, into table-slapping celebrations of the adrenal glands. Or, at least, that’s the case in Beowulf.

In EGO, they don’t quite hit the same, and I think it’s because of the difference in how they resolve. In Beowulf, if you reveal any matching symbols, you add them to your total. If you don’t reveal any, you take a Scratch—a more complex Offense Token—and your turn ends. There are two possible outcomes, one good and one bad. In EGO, if both cards match, you add them without consequence. If neither card matches, your turn immediately ends in embarrassment, but you take no Offense Tokens. If only one matches, you add it to your total and you take an Offense Token.

I understand the reasoning for this adjustment. Getting punished with a Scratch for bad luck isn’t pleasant, but complicating the rules for a Risk makes it less guttural as an experience. Your reptile brain can’t be fully in control when there are three possible outcomes. You have to pay attention. Plus, in EGO, when you draw that first card and it doesn’t match, you already know you aren’t getting what you want. You’ll wind up with an Offense Token or an ended turn. Drawing one card that matches almost feels worse than drawing none. In Beowulf: The Legend, if the first card doesn’t match, suddenly the second card has everything riding on it. If the second card is a miss, everyone appreciates your bravery/pigheadedness. If the second card hits, everyone cheers or groans or curdles like milk. It’s magnificent. Meeple Mountain’s own Thomas Wells described Beowulf: The Legend as “a game of brinksmanship,” and that hits the nail on the head.

Cleaner Isn’t Always Better

Every change in EGO makes sense to me. I don’t question Why You Would Do That. Beowulf: The Legend is a weird game to teach, full of counterintuitive details, and to publish it as-is in the retail market of 2025 would be suicide. It is, on the surface, an alienating game. But every little tweak in EGO, made sensibly in the name of approachability, has a downside for the emotional contours of the game.

Turn order has been inverted: the winner of each major Event takes the first player marker, whereas Beowulf: The Legend passes that honor on to the last-place finisher. It is much easier for a table to remember that the winner becomes first player, but there is now no reason at all to choose to come in last during an auction. In Beowulf: The Legend, if I know a card drafting Event is coming, I may intentionally drop out first so I can have first pick of the next litter. That’s more fun, and more interesting.

Offense Tokens are much more straightforward than Scratches. The first six Offense Tokens slowly decrease the bonus you’ll score come game’s end, and after that you start to lose points. Scratches are comparatively byzantine. Scratches themselves do nothing to your score, but three Scratches immediately turn into a Wound, and more than two Wounds will lose you a significant number of points come the end of the game. No Wounds will score you a significant bonus. If your goal is to make a game more approachable for the market, it makes sense to change that.

But that removes some exquisite points of tension. Taking a Risk in EGO means I might get an Offense Token. Okay. They’re fairly easy to get rid of and there’s no point of no return. Taking a Risk in Beowulf when you have two Scratches is a fraught decision. Scratches are relatively easy to get rid of, but Wounds are impossible to repair. The system for Scratches and Wounds may be relatively Baroque, but it is not needlessly so.

In the name of making the game default to a breezier play time, Bitewing also gave each System an optional modular board that adds a number of smaller Events. These, I would argue, are entirely necessary, and should just be part of the base game. They make the resource and hand management of EGO much more interesting. There’s no real reason to accumulate money in EGO without the occasional money auction. The yield for money at the end of the game without the extra boards isn’t sufficient. There’s also probably a case study to be done on the impact of the randomly ordered Systems versus the meticulously-laid-out-in-a-particular-order board of Beowulf: The Legend, but I am too tired for that study to be done by me.

My colleague Thomas also said that Beowulf: The Legend, and by extension EGO, doesn’t create meaningful decisions. Rather, it simulates the process of making meaningful decisions. I can see that, but I don’t think it’s a relevant critique in the case of Beowulf. Beowulf: The Legend inarguably gets a rise out of people. They get into it. It presents all of its opportunities in the most interesting experiential light possible. Whether it affords you real, quality decisions, or it simulates making decisions, it is fun. EGO, through no fault of its own, manages to reveal the limitations of the original design. It reveals Beowulf for what it is under the shiny armor and the masculine rigors: an okay game. EGO isn’t the problem. Beowulf is. It just happens to be that everything about Beowulf is, through either luck or intention, perfectly set up to mask its shortcomings as an engine for making decisions. It is instead content to be, and is, a blast. By brushing up the polish, EGO has unintentionally revealed that there was only so much shine to begin with.