This is the fifth volume of Perfected Game Mechanics (Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4), a series exploring games where, be they wonderful, amazing, inspiring, or even flawed in some ways, managed to utilize one particular mechanic with sheer perfection. That one mechanic is not going to be improved upon; there is nowhere “up” to go.

Note: the images representing the mechanics are from BoardGameGeek.

Critical Hits and Failures

Definition: When the dice are rolled, if the result is particularly low or high, then spectacular failures and successes are possible.

Rollmaster

Role-playing games date back to the 1970s. Dungeons & Dragons started a trend that was followed up with games like Traveller, Villains and Vigilantes, Boot Hill, Top Secret, and so many others. All of these games focused much of their rules on combat and adventurous survival. This was no surprise, as it was a natural extension of the war games that birthed the hobby. Early D&D spells, for example, were re-themed medieval weapons (e.g., Fireball was originally based on the effect of a Catapult). The problem for many started when the amount of damage needed to take out a character started growing (and growing, and growing).

The original versions of Dungeons & Dragons had nearly all humanoid races limited to single digit hit points. In those games, any particular sword blow, arrow strike, or fall from a castle wall might be the end of the hero. But when escalated hit points became common, warriors would wade into the fray with the absolute certainty that until they had been hit with at least a couple of dozen strikes, they were in no danger at all. Jokes were made extolling the fact that, per the rules as written, a 13th level fighter would survive a fall from literally any height. Something needed to be done.

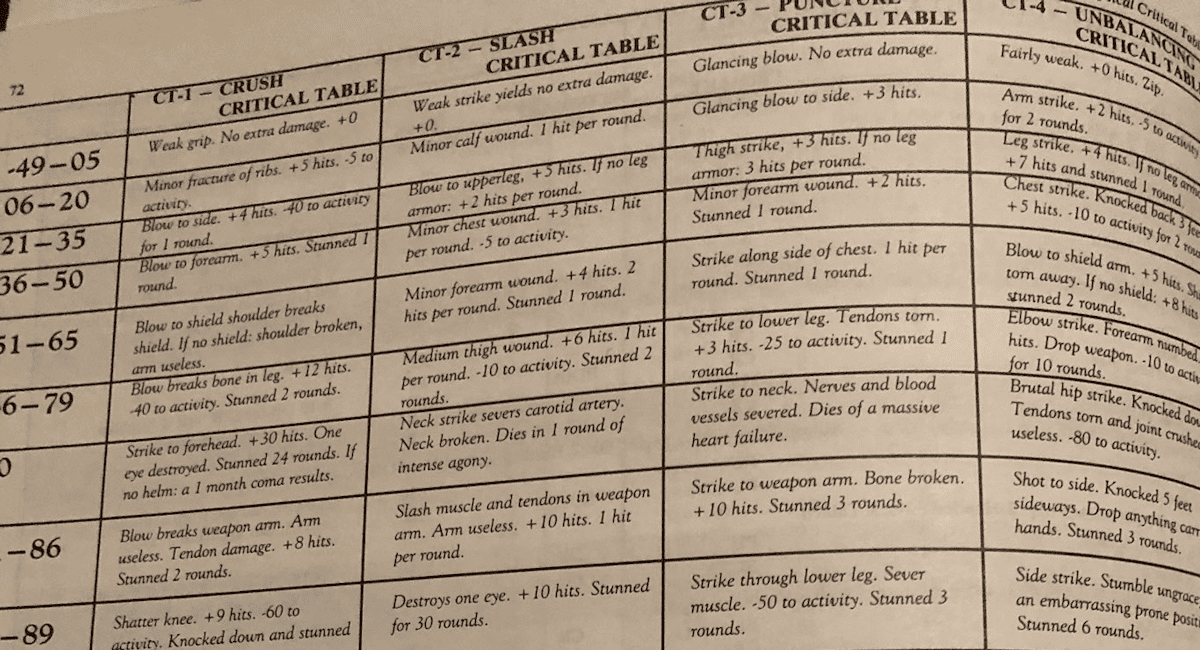

Enter Iron Crown Enterprises in 1980. Rolemaster was their system. The original set of books included Character Law, Campaign Law, Arms Law, and Claw Law. Both Arms Law and Claw Law had extensive charts detailing the effects of critical hits and failures (i.e., fumbles). The descriptions were not all simple, generic affairs such as +X damage, or ×Y damage. The charts and tables included graphic descriptions of instant death caused by slicing open the belly and causing the internal organs to spill out, or arrows going through eye-slits and doing damage directly to the brain. Each weapon (weapon group, type of natural weapon) had a separate chart with varying probabilities of extra damage or instant death, each accompanied by a gory description of the effect. It was beautiful.

Other games tried to follow suit. The July 1980 issue of Dragon Magazine (#39), for example, had an article called Good Hits and Bad Misses. But each attempt to capture this lightning in a bottle never quite reached the level of fun and narrative accomplished by the Rolemaster system. I knew of many who would borrow these books to include them in other games. I certainly did.

This is critical hits and failures perfection.

Events

Definition: via a variety of methods, events take place within the game which are completely out of the player’s control. These events can have anywhere from a minor to a cataclysmic impact on game play.

Kingsburg: To Forge a Realm

My colleague, Justin Bell, does not like random events. At least not the way they tend to be applied. I have spoken on this topic a few times (for example, in my review of Redsky). For the most part, I agree with Mr. Bell. Random events can be punishing to players for no reason at all. They can thrust a player into the lead or into the back of the pack, with nothing to indicate why this is happening other than the draw of a card, or the roll of a die, or through whatever methodology this mechanism is being implemented. Very often, the whole system just sucks.

In order for a random event system to work well, it needs to be handled in a way that it will not seemingly target a particular player, or cause such a swing in the game state that players find that the previous several turns were for naught. It needs to be subtle. It needs to be something that actually adds to the fun of the game.

Very few games have been able to thread this needle.

Kingsburg has a core game that has no need for a random event deck. The game plays perfectly well without it. It also plays perfectly well without variable player powers, customizable player boards, variable powers and effects on the main board and so on. The game does include all of these options in the expansion material, Kingsburg: To Forge a Realm. If you like variable player powers, you can add that. If you like random events, you can add that as well (or instead). And so on. Everything that can put such variability into the game is an optional rule that comes in an optional box to be ignored or included as desired.

The random event deck is mostly made up of minor effects. Only one event is played per round (year). There are a few that can be more difficult to deal with, but nothing crippling. The events that were most humorous to our group were the two cards in the deck that indicate that the king is sick. The only effect is that he cannot be selected on the main board for that round. But, if both of the “king is sick” random events come up in the same game, then the king dies and the game ends immediately. We laughed hard when this happened. The king was sick in round one, then he died in round two. A very short game, indeed. We continue to laugh about it years after the fact. And yes, we scored things, determined a winner, and immediately set up for another game.

This is random event perfection.

Hidden Victory Points

Definition: Players collect victory points, but this is not public information.

Concordia

There are 429 games listed on BoardGameGeek with this mechanic. Not all of those listed are games I would agree are actually using Hidden Victory Points in the most technical sense: I am looking at you, Ra. If you take a little time to give more than a cursory glance, really looking at the games in that list, you soon realize that Ra can be easily forgiven since the vast majority of those games do not so much hide victory points as much as they obfuscate them. Take Small World, for example. The victory points are accumulated at the end of each turn. Everyone knows how many each player accumulated. Players can spend them when taking on a new race-plus-power combo. If a player desired, they could keep track of every point each player accumulates and spends. So are they hidden or just obfuscated?

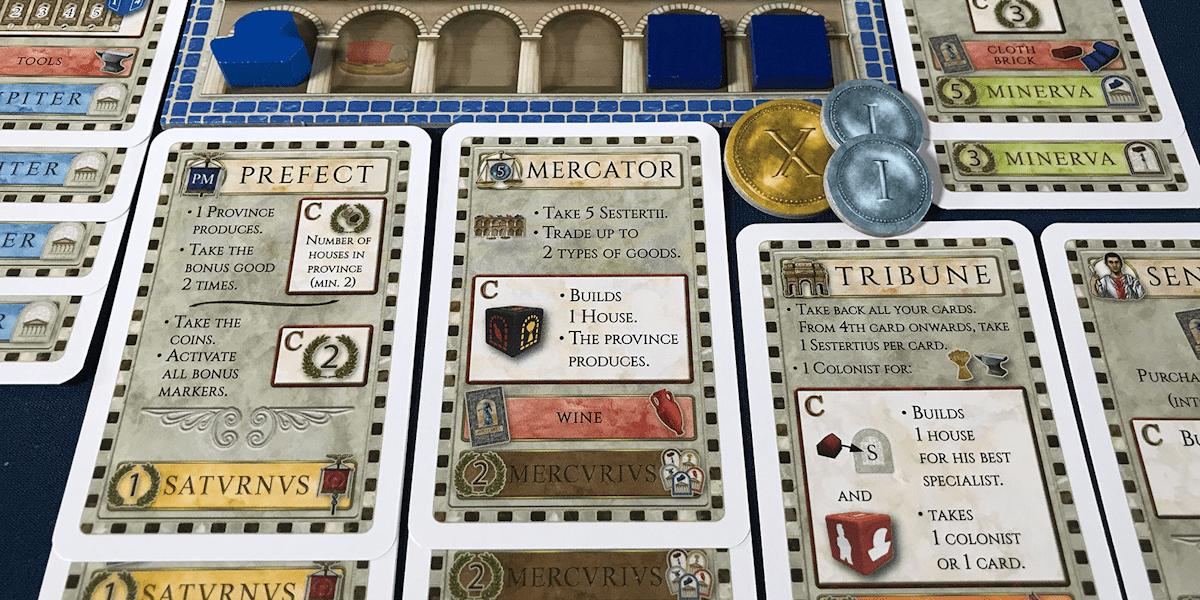

The highest ranking game with this mechanic, Concordia (#26), obfuscates as well. The method it uses is so good that each player has only the blurriest view of their own points until the very end of the game. Concordia uses a Hand Management system expertly blended with its Action Retrieval, Deck Building, Set Collection, and (yes) the Hidden Victory Point mechanics. These are so well blended, players will rarely think of these mechanics as anything other than one, single, all-encompassing, and beautiful thing!

The cards in your hand are the actions you are taking, the deck you are building, several of the sets you are collecting, and the victory points you are accumulating. As you maneuver about the map with your soldiers and ships, establish houses in various cities, and gather resources… Those resources are often used to obtain more action cards. Each action card allows more opportunities to maneuver, establish houses, and gather resources. But each of the action cards also represents one of the gods. Each god is looking for a specific thing: types of cities (e.g., Jupiter wants cities that do not produce brick; Mercury wants a variety of goods being produced), being spread out (e.g., Saturn wants a house in each of the twelve provinces; Mars wants soldiers and ships on the board), and so on. The favor offered to those gods generate victory points. The most victory points wins.

Sure, players could keep track of the gods each player accumulates, but the value of each god is in constant flux as new houses are established. It would be a massive undertaking to keep track of other players’ points. It is too much for the players to keep track of their own most of the time. Granted, near the end of the game, good players will be looking at their decks carefully and seeking to ensure they maximize their points as best they can.

This is hidden victory point perfection.

Ladder Climbing

Definition: After a player plays a card or set of cards, the next player must play a similar set of cards of a higher value (sometimes a game allows plays of an equal value). The last player to play gets to start the next round.

The Great Dalmuti

Richard Garfield produced three games that, in the 1990s, occupied a lot of my time. The first is one that will be obvious (especially if you read my other stuff): Magic: The Gathering. The second is a game that was fun, but we had to add so many house rules to reign in the game that we just do not play it anymore: Robo Rally. (What I have read of the latest editions, they may have cleaned things up. I might have to give it another try). The last one is The Great Dalmuti.

There are many ways of handling the Ladder Climbing mechanic. The best do it well (e.g., Blue Moon). Others just do it to do it (e.g., Gang of Four). The worst completely miss the mark (e.g., Cradle to Grave). All that said, Richard Garfield created a game where the Ladder Climbing mechanic was all there was. The game stripped out nearly everything else. The only two portions of the game that are not Ladder Climbing, is the steal and the coup.

- The Steal: The lowest ranked player (the greater Peon) has to give the best two cards they have to the highest ranked player (the greater Dalmuti). The greater Dalmuti gives the greater Peon any two cards from their hand. The next lowest ranked player (the lesser Peon) has to give the second highest ranked player (the lesser Dalmuti) their best card. The lesser Dalmuti gives the lesser Peon any one card from their hand.

- The Coup: If one of the two lowest ranked players (the peons) have both Jesters, a coup takes place. They each swap places with the Dalmutis and the game continues.

The deck creates tension in the Ladder Climbing by being a pyramid. In addition to the two jesters (wild cards), the deck consists of one card at rank 1 (the Dalmuti), two cards at rank 2, three cards at rank 3, and so on until you get to twelve cards at rank 12 (the Peasants).

At the start of a deal, the Great Dalmuti plays any number of cards of the same rank. Each player in clockwise order plays the same number of cards of a lower rank or passes. The last player who can play starts the next round with any number of cards of the same rank. Anytime a player empties their hand, they are removed from the deal. But this is a good thing! The first person to go out becomes the Greater Dalmuti in the next deal. The second becomes the Lesser Dalmuti, and so on. The last two with cards in their hands become the Peons.

Note, you can win a deal, then lose… there is no ultimate winner. It is all about the game. And that would be rather stale were it not for the social implications the game imposes. The Dalmutis are to have comfortable chairs; the peons are to have no chairs and must kneel while in that position. The Greater Dalmuti is the dealer, but it is the Greater Peon who shuffles the cards, offers the Greater Dalmuti the cut, then deals in the Great Dalmuti’s place. And so on.

When we played the game back then, we had a house rule: at the start of each deal, the Greater Dalmuti could institute a rule. This rule could not impact the game, only the social atmosphere. So, a rule might indicate that the Peons are not allowed to speak. Or that everyone needed the Great Dalmuti’s permission to leave the table for any reason (e.g., go to the bathroom). Or all sentences had to be spoken with their words in the reverse order. If you pay attention to the social aspect of this game…

This is Ladder Climbing perfection.

Tile Placement

Definition: players place tiles to either score points or trigger actions. Tiles might be viewed as being in clusters, or part of a particular group.

Carcassonne

Tile placement is a mechanism that has been used a lot in modern board gaming. Over 9,000 games are listed in BoardGameGeek as using this mechanic. This list includes many of the most popular games ever created. Those in the top 50 include: Brass: Birmingham (#1), Arc Nova (#3), Terraforming Mars (#7), The Castles of Burgundy (#16), and A Feast for Odin (#25).

Although Carcassonne ranks at #232 at this point, this quarter-century old game still shines as a beautiful example of what tile placement can be. The base game includes cities, cloisters, fields, and roads. Each has its own way of scoring (i.e., number of tiles in the city, a completely surrounded cloister, length of the road, and the number of completed cities the field touches). The game has no obvious, direct conflict–but the ways in which another player can put a wrench in your plans, or steal your features are numerous.

In the end, it is the simplicity of the common board being built as the game progresses that makes this game approachable, easy to explain (except, perhaps, the farmers in the field), and so enjoyable. The only drawback to the success this game enjoyed over the years were the expansions.

Many expansions came. Some of them were interesting (e.g., the two river expansions, the mayor who can only go into cities, the abbey which can be placed next to anything, etc.) and some fell flat (e.g., the tower which added direct conflict, the circus which added a dexterity game, the wheel of fortune which made the start of the game far less interactive, etc.).

In the end, this game is the one that inspired many, many other designs (e.g., Dorfromantic). It has a lasting legacy that will not be soon forgotten.

This is tile laying perfection.

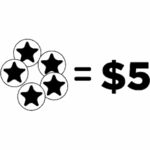

Victory Points as a Resource

Definition: players may use the points they have acquired as a resource to gain other resources or advantages within the game. Care needs to be taken to ensure that the points one can gain from the purchase are greater than the cost paid.

Small World

I mentioned this game above. Although not exactly foreshadowing, I will say that my view of this game is significantly brighter than my colleague, Bob Pazehoski’s. Although I tend to agree with him when it comes to the sheer number of pieces this game has, I prefer to play this over the table as opposed to over the internet. It is a wonderful visual and tactile experience.

Victory points in this game are represented by coins (in denominations of 1, 3, 5, and 10). Each player starts with 5 coins in their stash. The number of coins anyone has is not public information. Players take on the role of various races which have been paired with a power. These pairings are random, so in one session you might have Alchemist Giants or Pillaging Tritons, while in some later sessions you will find Alchemist Ratmen or Forest Tritons.

There is a market of these combinations, and it costs you nothing to take the one furthest from the deck; it costs you one coin (placed on each skipped combination) to move past the furthest combinations and select the ones that most recently became available. This is the only way coins leave a player’s pool. If a player later selects the race and power combo others skipped, they get those coins that were spent skipping it. At the end of each player’s turn, they will accumulate coins based on the number of regions they control, and the nature of the race and power they are playing (each race and power may have special scoring conditions which can generate additional coins). The game is not too complex at its core.

Spending coins–victory points–to skip available races and move to another is simple. It is a small thing, to be sure. Yet, knowing when to spend those coins is a major part of winning. The mechanic is handled simply, in a straightforward fashion. It does not even draw attention to itself. The fact that this mechanic is used in such a minimalist fashion is a boon to its effectiveness.

This is victory points as a resource perfection.

Final Thoughts

Six games where each represents perfection in a specific mechanic (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda). Each has flaws, but they are eclipsed by the greatness within. Were I to give each game a full review, none would be rated below four stars. They are great games!

What other games have managed to perfect a mechanic? Meeple Mountain will delve into others in future articles. In the meantime, what games have you played where you noticed a particular mechanic transcending its use elsewhere? Did the rest of the game measure up? Let us know in the comments!