Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I love word puzzles. I was raised on a subsistence diet of the magazines Games and World of Puzzles, and of Dell Magazine’s endless string of publications. Dell never had the best puzzles, but the sheer quantity is staggering. One imagines an office full of interns, slaving away to form the most satisfying Crostic imaginable. Even at that pace, they couldn’t keep up with demand. I went through one of those tomes a week, which is crazy to think about now. Where do kids find all that time?

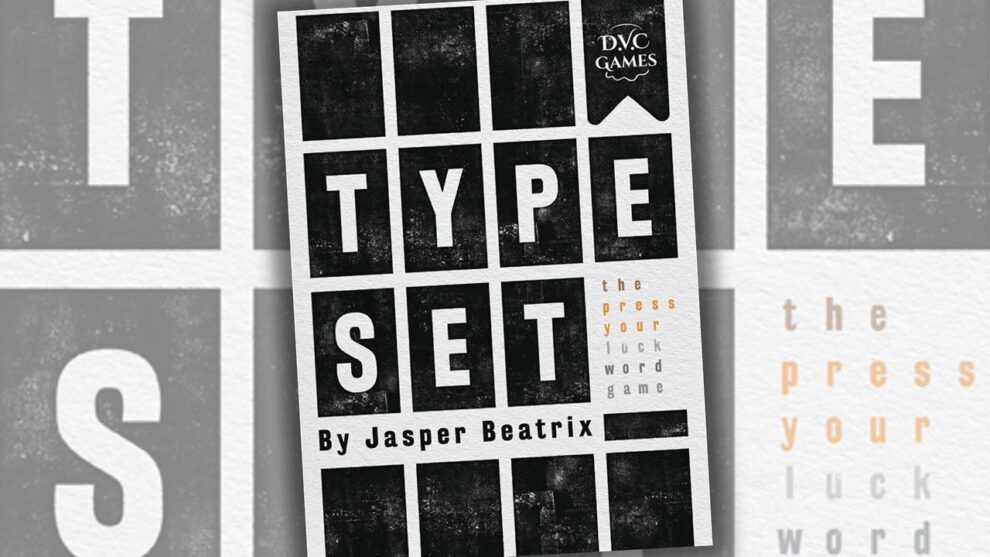

Within the world of contemporary board games, word games are plenty popular, but there aren’t many that qualify as word puzzles. It’s an important, meaningful distinction, though I’m open to this being a bug/insect situation. Word games are typically associative, about the meaning of words. Codenames, Just One, and So Clover are all word games, but none of them are word puzzles. Word puzzles play with the words themselves, the matter of words, with letters and syllables. Bananagrams and Scrabble are the most popular examples. Letter Jam is another. Typeset, from the design team at publisher D.V.C., is also very much a word puzzle.

Kerning

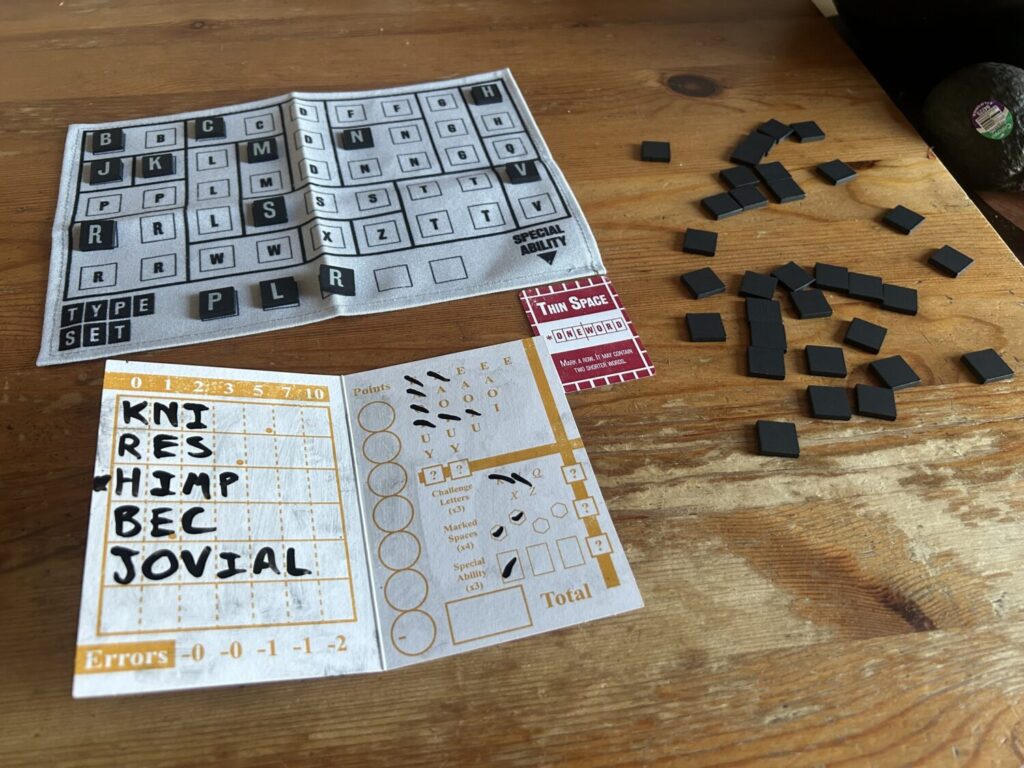

The goal of Typeset is simple enough: spell long words. The meaning of words is irrelevant here, so long as you know how to spell them. Each player is equipped with a dry erase booklet and a dry erase marker. On the left side of the booklet are six rows with seven slots. It is into these rows that you will ultimately create your words out of the letters revealed during each round.

A turn is extremely simple, at least in terms of what you do physically. Cognitively, maybe not so simple. Draw a tile from the supply, reveal it, and then everyone makes a decision about where to add that letter on their board. You can choose any row you want, so long as you put the letter in the left-most empty space. Each round consists of five turns, and you can always choose to drop out between rounds.

A spelling game in which you have no control over the letters you use sounds like an invitation to disaster, but Typeset makes a number of smart choices that keep the game sensible, interesting, and rewarding. For one thing, you can always skip a tile. Well. I say “always.” You can skip a certain number of tiles, though it’ll start to cost you points.

Every game gives players access to a special ability, drawn during setup from a deck of possibilities. These allow for all sorts of shenanigans. It might let you reorganize all the letters already written into a particular row, or change a single letter to the letter that precedes or follows it in the alphabet. My favorite is Minding, which lets you rotate one letter into another. You can turn an M into a W; a B into a D, a P, or a Q; or—as representative of the D.V.C. project as anything—an N into an S or Z. Knowing the special ability in play from the start of the game gives you a little extra room to plan.

Another reason the game not only works, but excels: tiles don’t contain vowels. While the flow of consonants is entirely up to chance, you begin the game with a reservoir of vowels available to you. Need an “E”? Go on, tuck in.

You also have a variety of means by which you can earn wild letters as the game goes on. If you use one of every vowel, including “Y,” you get a wild. If you get four words going on your board, you get a wild. If you place three out of the five Challenge Letters—J, K, Q, X, and Z—on your board, you get a wild. You also get a wild if you use the special ability three times.

What I noticed after two or three plays, what impresses the heck out of me, is that all these wild incentives also incentivize you to make full use of the decision space. It would be pretty easy to play Typeset without thinking about “Y,” but failing to do so will keep you from getting two wilds. If you were playing purely on the odds, skipping the Challenge Letters would be as good a use of your skips as anything, but, again, you’re encouraged to make use of them. It makes the game more challenging, and it makes the game more interesting across multiple plays. Very smart stuff.

Letters Jam

Part of what sets Typeset apart from most puzzle games of any variety, let alone word puzzles, is its arc. In the early stretches, the game elicits a feeling remarkably similar to the creative process. As you write down the first few letters, the air crackles with energy and excitement. You don’t know what your words will be yet, and every new tile either introduces new possibilities or further defines previous choices.

Towards the end of the game, when your words are set and there’s little room for improvisation, Typeset becomes a different experience entirely. It becomes a tense matter of pushing your luck, an addictive and compulsive slot machine. You score points for the length of each of your words at the end of the game. As words get longer, their scores increase. This incentivizes you to think of big words and to stay in the game for longer, but you also lose points for any incomplete or illegitimate words on your board. This incentivizes you to play conservatively. The cross currents of these two incentives makes for a seriously compelling experience.

Most word games don’t have an arc, at least not one this well defined. Bananagrams, which I adore, comes closest, but even Bananagrams doesn’t have an arc so much as the game consists of two phases. In the first, it’s a frantic scramble to get your grid established. Once that’s handled, it becomes a persnickety game of minor adjustments. Each half of the game is pronouncedly different from the other, and there’s a firm transition point. You can also always undo your work in Banangrams, rearranging tiles to accommodate an unwelcome Q or intruding K. Typeset is in some ways a crueler mistress, and it slowly transitions you from freedom to agony as your decisions catch up with you.

While it is entirely multi-player solitaire, a group game of Typeset is filled with commiseration, with the joy of hearing others—or even yourself—mutter swears under their breath. It is a game that often culminates in everyone simply losing the will to continue, but occasionally erupts into absolute triumph. All the way, your brain is on fire, juggling the possibilities of how you might see through six different words.

While I have yet to play any two D.V.C. titles that have much of anything in common in terms of their mechanics, they all share a common focus on player creativity and agency. If Bananagrams kicks off with a dizzying and frenzied burst of permutations, Typeset slowly unfurls. It’s a game that asks you, challenges you, to figure out the best that you can possibly do with the materials as presented. It demands constant creativity, a litheness that I adore, and it ends, if you’re brave enough or foolish enough to make it to the far reaches of each of your rows, in a sweaty mess of pushing your luck.

What matters most to me, of course, is that it plays wonderfully alone. It’s easy to set Typeset up for a quick solo play, in and out in 10-15 minutes. I may not have the infinite expanses of time that allowed me to consume whole issues of Dell Magazine’s Variety Puzzles, but I surely do still have the time for the occasional game of Typeset.