I’m a sucker when it comes to Uwe Rosenberg. Ever since I played Agricola for the very first time way back in 2007, he’s become a designer that never fails to pique my interest. At some point, I went from merely being a fan to being an avid collector, with nearly 70 unique Uwe Rosenberg games collected thus far. Today, I am writing about one of his more obscure, early efforts: Titus.

Titus Caesar Vespasianus was Roman emperor from 79 to 81 AD. And, honestly, that’s about all you need to know to play this game. In fact, even that’s too much historical background because, as far as theme goes, this game is completely devoid of it. At its heart, it’s an abstract, pure and simple. It may as well have been called “Coin Flip” for all that Titus has anything to do with it. In fact, if you ask me, that would have been a far more clever, and accurate, title for this game.

Published by Adlung-Spiele in 2000, Titus is a svelte little card game about collecting sets of cards in order to score victory points, but don’t let its small size fool you. It’s much more difficult than it sounds. Titus is a game that will not only require you to think tactically, but will put your memory to the test as well.

Let’s learn how to play.

Setup and Concepts

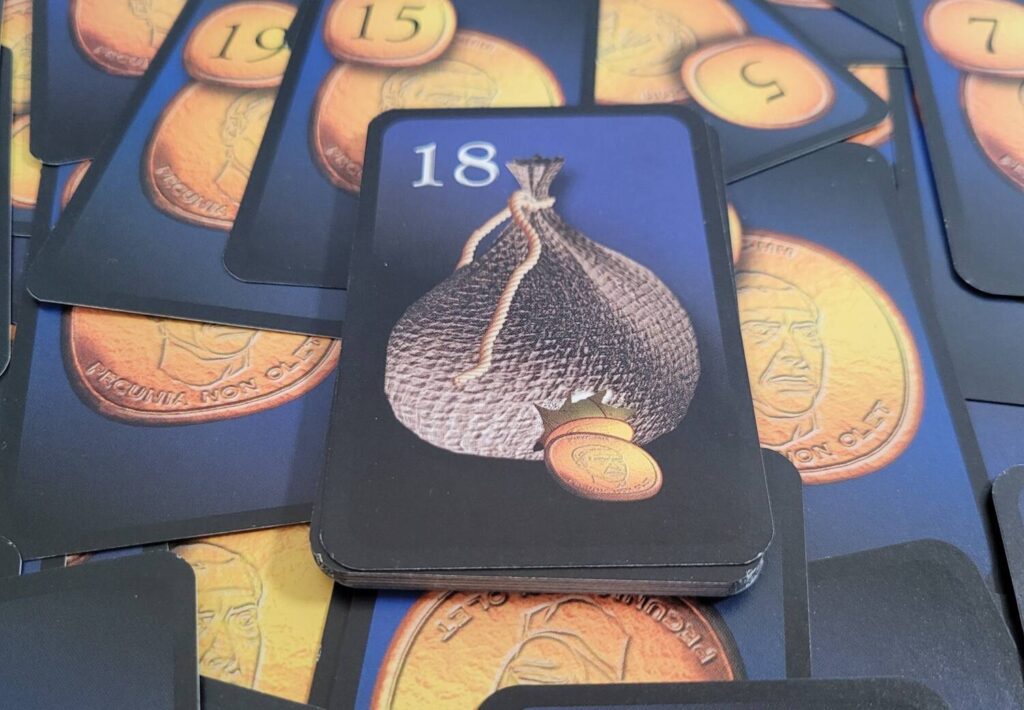

There are two types of cards in the game—Money and Victory Point cards. The Victory Point cards are arranged by value and placed into a face up stack in descending order. Then, the Money cards are shuffled a few times, that deck is split in two, one half is flipped to its opposite side, and the deck is shuffled some more. This is because, unlike most traditional card games that feature a distinct front and back side on their cards, the fronts and backs of Titus’s cards feature different numbers, ranging between 1 and 19 in value. That being said, the values on opposing faces never differ by more than a value of 2. So, if the card you’re looking at displays an 8, you know that the back side of the card is a 6, 7, 8, 9, or 10. Keep this in mind as it will be important later.

Each player’s play area is referred to as their ‘store’. Each store will contain that player’s collection of cards. Cards that are part of a ‘sequence’ are arranged in a player’s store in a group in descending order. These cards are considered to be ‘connected’, while cards that are all by themselves in the store are considered to be ‘singles’.

Players are trying to create sequences of Money cards in order to claim Victory point cards. Once a Victory Point card is claimed, it is kept in the player’s playing area along with the Money cards used to claim it. The rule book doesn’t give this scored sequence a special name, but I will refer to it as a ‘scored set’ for the purposes of this review.

Your Turn

Your turn consists of choosing between one of two options: drawing a card from the top of the draw pile (without anyone seeing its opposite side) and then doing something with it OR drawing the top card off of another player’s scored set and placing it into your own store, after flipping it to its opposite side. If drawing from the draw pile, the card you draw can be used by you in one of two different ways: place it into your store or trade it for a single in another player’s store.

If trading the card with another player, the card you drew is placed in their store, and you can take one of their singles to place into your own—but when you do, it is flipped to its opposite side so you can never be sure what number you’re going to get unless you’ve seen the other side of the card before and have a really good memory. Any card placed into your store is initially placed as a single. As a free action, you can attach singles to groups of cards, groups of cards to other groups of cards, or groups of cards to singles in order to create sequences (i.e., a run of sequential numbers). Each sequence created in this way must be arranged with the largest number on top and the rest situated below it in descending order with the numbers on each of the cards visible.

If placing a card into your store results in a sequence being created, you get to take another turn. But, if the card is added to your store and does not result in a new sequence, your turn ends. It is worth noting here that you are never forced to connect cards together to create sequences. But, if you do, those sequences can never be split apart. You can only take an extra turn twice, at the most, before play passes to the next player. This limitation is removed for the player who is furthest behind (as a catch up mechanic).

At any time during your turn, as a free action, you can cash in a sequence composed of at least four cards to claim the highest valued unclaimed Victory Point card. The sequence of cards used to claim it are then placed on top of the Victory Point card in descending order. No more cards can be added to this scored set for the remainder of the game but, as described earlier, cards may be taken from it by other players. If there are no more Victory Point cards left to claim, you just keep building sequences in your store.

End Game and Scoring

The game ends as soon as the last card is drawn from the deck of Money cards. Then, players score points equal to the points printed on the Victory Point cards they’ve collected as well as six points for each completed sequence in their stores.

“What is a ‘completed’ sequence?” you may be asking. That’s a great question, and I wish I had a definitive answer for you. However, the rule booklet never defines this, nor does it provide any end-game scoring examples. I assume that a ‘completed’ sequence is the amount of cards you would need to claim a Victory Point card if there were one to claim, so that’s how I play it. This would be the reason a player may not want to automatically connect sequences in their store during their turn.

Thoughts

Here’s an example of the mental gymnastics Titus will demand of you.

Imagine a situation in which you’ve taken a double-sided 4 card from an opponent, and now it’s sitting in your store. Later on, it gets taken by another player and then they wind up adding another couple of 4 cards to their store. Even later, you find yourself in a situation where you really need a 4 to create a sequence. You know that opponent has a double-sided 4 sitting in front of them, but which is which? Guess correctly, and your turn continues. Guess wrong and your turn comes to an end.

Now, this isn’t a hypothetical situation. This happened to me in a recent game. I really thought I remembered which of the 4s sitting in front of them was the one they’d taken from me earlier, so I confidently traded the top card of the deck for it knowing that I was about to create a sequence, claim a Victory Point card, and take another turn immediately thereafter. The shock I received when I flipped that card over to find something other than a 4 on its reverse side took the wind right out of my sails. How could I have gotten it so wrong?

Titus can feel frustrating at times. Unless you have an eidetic memory, the memory element of the game will quickly go out the window, and the game turns into one based purely on intuition and hope. I think that what makes that aspect of the game so frustrating is that early on, when there aren’t as many cards dealt out, and where cards tend to remain with the people that drew them in the same state as which they were drawn, it’s not hard to remember what’s what. It leads you into a false sense of security where you believe you’ve got the data retention chops to do well. But, then things quickly get out of hand, and that makes you feel the exact opposite of the way you felt early on. And nobody enjoys feeling like they’re an idiot.

At first, Titus made me feel that way, and I was recoiling at the sensation. But, then I had the realization that nobody at the table was able to recall where everything was, and that everyone I was playing with was going through the exact same thing as me. We were all on even footing. When I realized that, I was able to ease up on the self-doubt, and I started having a lot of fun. Titus may just be a deck of 64 cards in a small tuckbox, but there’s a lot of game packed in there.

While the memory element is definitely important, there’s a lot of tactical and strategic depth as well. When the game begins, it’s a race for the Victory Point cards. But, as those cards begin disappearing, players can look around the table and quickly calculate whether they’ve fallen behind and, if so, by how much. And, if you’re in the back of the pack, those leftover banked sequences that are worth six points each at the end of the game begin to look very appealing. And, it isn’t hard to find the cards needed to create them. They’re right there in other players’ banked sequences.

If you’re the player in the lead, this can become very worrisome. You want the game to end while you have the advantage, so burning through the deck becomes your highest priority. The longer that gets put off, the more tenuous your hold on the lead becomes. It is in these closing salvos with players juxtapositioning for the lead, trying to set things up to bring the game to an end when it is most fortuitous to themselves, that Titus really shines.

By nature of being an unassuming card game squirreled away inside of an equally unassuming, ugly little tuckbox, Titus isn’t doing itself any favors. In a world of flashy games with amazing production value, this is a game that it’s difficult to convince anyone to play. But, once they give in to my incessant badgering and actually give it a try, they’re always delighted by the experience that follows.

If you’re able to find yourself a copy, I highly recommend this game. It’s a testament to the designer that Uwe Rosenberg would go on to become, and a firm reminder that sometimes good things do come in small packages.