Opening Overture

I recently took a holiday in Salzburg, Austria, where my wife and I roamed the historic streets nestled in the Alps. Everywhere we looked was the pride of Salzburg, Wolfgang Mozart. We saw his birthplace, his residence and, to the delight of my ears, even attended a string quintet concert at the Fortress Hohensalzburg. It was quite warm sitting in a nearly millennium-old building with no air conditioning, but I digress. Weeks later, Luthier hits the table, and I smile as memories of concertos, operettas, and sonatas come rushing back.

I’ve always kept classical music as the zen-encompassing soundscape for my apartment, especially during working hours. My Google automation has me saying “Good morning,” to which the crescendos of chamber music from Chicago’s 90.9 WFMT fill the air (who could also use your support as a public broadcast station). My favorite classical track of all time is The Planets – II. Venus, The Bringer of Peace by Gustav Holst, and I’m listening to the opening adagio as I write this.

Luthier is the second, highly thematic game from Dave Beck. His freshman title, Distilled, while charming on the macro level, didn’t stick with me on the micro level. I recall my main criticism being the ingredient shuffling and the amount of chance involved.

When I saw Luthier earlier this year at the GAMA (Games and Manufacturers Association) Expo, I was hesitant, and foolishly, I kept walking by. Which was also a misstep, considering Dave Beck is a fun guy and worth chatting with if you ever get the chance.

It’s unfair to judge new titles based on previous work, but there’s always growth, and in an industry of constant new releases, it’s easy to dismiss something too quickly. I heard rumblings that Luthier was, in fact, really, really good, but it wasn’t a priority play for me until my friend practically dumped it in front of me. And boy, am I glad he did.

Just as in a symphony, after the overture comes the work itself. Let’s take a closer look at how Luthier plays.

Maestro, if you please.

Mass in B Minor

Luthier sends players to the classical era of Europe, working to court patrons with masterfully crafted instruments and performing various repertoires of music. Over six rounds, players bid their workers around different action locations—gaining, building, or repairing instruments; wooing patrons; performing; or trading at the market all while racing to claim first-chair positions in the grand orchestra.

In turn order, players secretly place their workers (essentially poker chips) that vary in strength from one through five. Assistants can also be added to enhance strength by one. Players’ chips are stacked on top of each other, indicating the possible turn order in which each action will resolve. Higher strengths move up the queue, but ties go to the player who placed earlier. While there’s no minimum strength required for an action, bonuses such as track bumps, resources, or other effects trigger if the specified strength is met.

Once all workers have been placed, players (in turn order) choose an action to resolve fully with everyone’s workers. Timing is crucial here, as some actions provide resources to pay for later ones. If things don’t resolve in the order you need, be ready to pivot!

Intermezzo

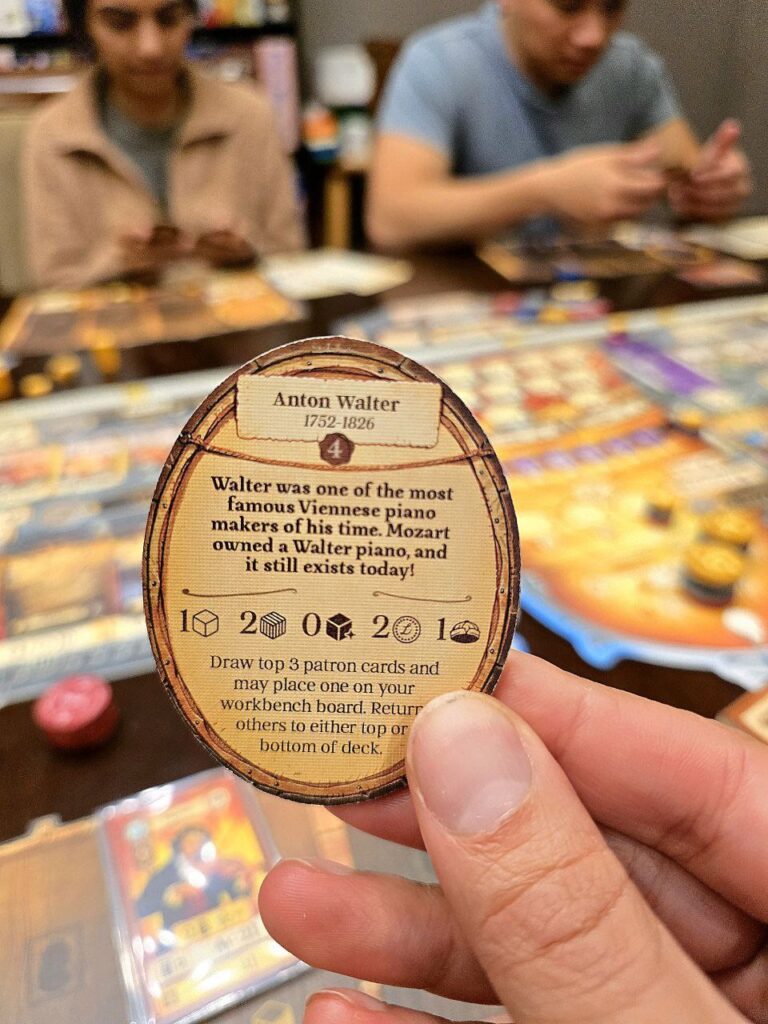

Patrons come in a variety of flavors and require certain types of instruments to be built or specific kinds of music to be performed to gain their patronage. However, idle too long, and the impatient patron will leave to pursue someone else, resulting in negative points. While the patron occupies a player’s workbench (board), gifts will be showered each round in the form of money or resources until they’re completed or timed out.

Completed patrons are flipped over and provide ongoing benefits, whether that’s a discount or a steady income drip.

Instruments are first “roughed,” paying a number of resources, then “finished,” both of which are separate actions. Finished instruments are placed into the orchestra for their respective first-chair positions. These trigger additional bonuses, and only one first chair can be occupied. Mixed into the deck are “rare” instruments that can occupy a separate first-chair section, allowing for infinite instruments to be placed.

Players can also repair instruments to add repair tokens or perform songs to add music tokens into the orchestra, helping with the area-majority aspect of the game (more on that later!).

During action resolution, players can also visit the market once per round, where resources can be bought and sold, and a single-use assistant can be hired for the subsequent round.

First Act Finale

Most points are counted in real time — stemming from built or repaired instruments, completed patrons, performances, and claimed achievements. However, a large chunk comes from the end-of-show scoring in the orchestra.

Players score for the number of first chairs they occupy, summing up the area-majority game. Built instruments always take the first-chair position, but if none are present, the chair is decided by the majority holder of repair and performance tokens. Add in private objectives, leftover resources, and remaining finished instruments, and that’s the show, folks!

Aesthetic Harmony

The biggest appeal of Luthier is the theme, and it’s absolutely dripping with it. With beautiful art by Vincent Dutrait and Guillaume Tavernier, the game pops like something painted on a fresco. Though I will say, the black-and-white cube symbols for resources made differentiating them slightly tough. The visual immersion is unmatched, but tying the theme to mechanics is on the softer side.

Though you’re running around collecting things to turn in and satisfy requirements, it doesn’t feel mechanically unique. It has a nice thematic coating around its actions, so it may feel “dressed up,” but building a trumpet versus a timpani drum ultimately hits the same note.

That’s not necessarily a bad thing, just an observation about an otherwise majestic centerpiece production.

To create even more immersion, Paverson Games has composed an official soundtrack featuring 70+ classical bangers!

Tempo and Timing

It’s been a while since I’ve played something where turn order mattered this much. Placing workers is all well and good, but don’t expect that action to resolve when you need it to. At the beginning of each round, you might have a plan that nets the best results, but that’s the best-case scenario. The game is heavily reliant on planning, but others are trying to do the same. Playing your highest-strength worker locks down what you need in one spot but leaves you weaker elsewhere. And since each location adds a bonus for using a minimum strength, it adds another layer of tough decision-making.

I’m not the biggest fan of auction or bidding games, but the system here is well executed and keeps tensions high with every placement and resolution. Every action sees someone sigh in relief while another punches the air in frustration.

Going last hurts, but the only way to move up is to take the balcony action, which claims achievements or grants money. It feels rough in a game where you start with only three workers (two more unlock in later rounds). It’s an interesting sensation when you use the current round solely to set up for a better next one.

Concerto for Four Players

On the surface, it looks like a “multiplayer solitaire” experience, but it’s highly interactive in the best ways. Because first-chair positions are tied to specific instruments, there’s a constant scan to see what others are working on. Many patrons require specific music to be performed, and it can turn into a knife fight to grab those songs first. Keeping tabs on your opponents can give you educated guesses on where they’ll place workers and where some “cheap” opportunities might lie.

There’s also the added wrinkle of tiers. Nearly every action (Repair, Guild, Salon, Perform) has two cards that can be claimed at no additional cost (tier one) and two that escalate in cost (tiers two and three). This adds even more importance to turn order and strength, and it’s easy to get hosed and left with pricey options. Players can unlock the higher tiers (meaning no extra cost), but that requires advancing up a balcony track.

Efficiencies can be built across three different tracks. One (Repair) improves your workbench, allowing multiple instruments per action. Another (Perform) enables rerolls and better dice for nailing that perfect performance — the most “luck-driven” part of an otherwise deterministic game. The last (Balcony) eases costs and adds bonus points for completing other actions. I found that while you don’t need to invest in all three, the Repair track is significantly more powerful than the rest, as it improves your workbench.

Ode to Joy

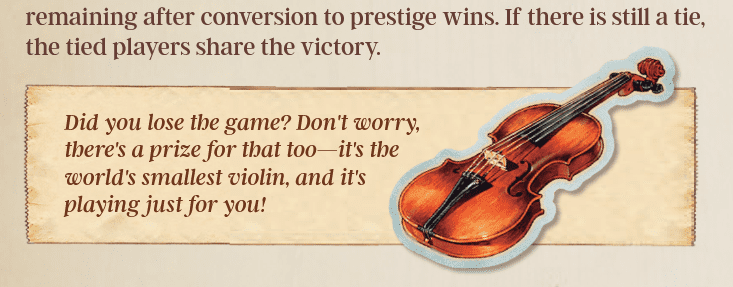

Luthier is fantastic, and I was a fool to walk by it months ago. Every action and decision feels important, and no turn feels wasted. The action economy is procedural and rewarding, building steadily toward your goals. The game is surprisingly cutthroat, which makes sense, as any band member knows being first chair is fiercely competitive. As “warm” as the theme may appear, expect to get snaked often. This is by design, and I love it. The look on someone’s face as you take the only piano they were waiting for—it’s the perfect time to play the world’s smallest violin.

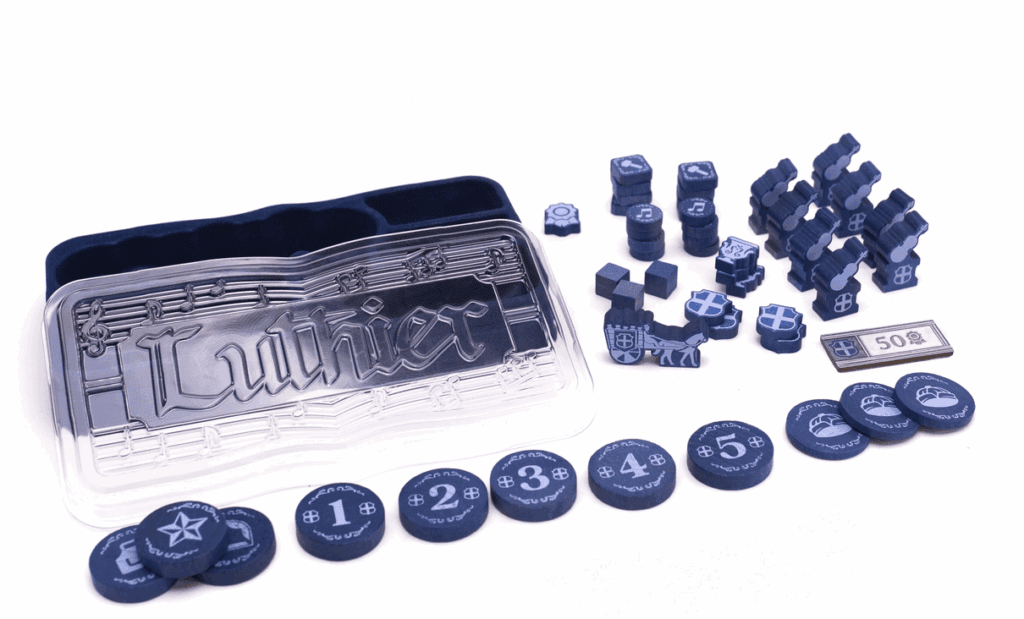

It’s a Euro that feels accessible to non-hobby gamers, but much like the musical world, it’s practice, practice, practice. Like Distilled, the box includes The Rehearsal, a predetermined, scripted version to help teach players what to do and why it matters. Also included is a lovely conductor’s baton to lead musicians across the board. The rulebooks are well-written and easy to follow, and the quick-reference points throughout make clarifications painless.

But like a misplayed note, there’s a jarring issue: playing time. The box says 90–180 minutes, and that’s a pretty conservative estimate. Playing with three or four is easily 3+ hours. That’s likely a barrier for many. As good as Luthier is, it’s a game you have to plan for. It’ll take up the whole night and can slow to a crawl with analysis paralysis. Since it’s highly tactical, expect frequent pivots. Even with experienced players, it only speeds up slightly. I feel the game could benefit from some condensing, though I’m not sure what could be trimmed. It’s optimal at four, but that comes at the price of time. It actually feels most tense at two, as every spot becomes a bluffing exercise. And like every modern Euro, there’s a solo mode pitting you against an automa.

There are multiple paths to victory, though they’re not obvious on the first play. Early rounds feel cramped as everyone rushes to the same spots, but as the game progresses, players find their lanes and the board opens up. Still, not all strategies are equal—some are simply better. Building instruments seems the best route, requiring more steps but rewarding more deeply. Other paths, like repairing and performing, feel more like side quests or mini-games—helpful in the immediate, but not as lucrative.

There’s enough here to keep replayability strong. Starting families offer asymmetric powers, from extra workers (very powerful) to a starting repaired instrument or cash instead of resources. And in a game where money is tight, being rich feels great. Players can also unlock specialty workers with game-breaking powers, adding even more variety.

At the end of Luthier, you’ll feel satisfied with what you accomplished and frustrated by what you didn’t. You’ll likely curse whoever snaked your perfect plan, but you’ll come back sharper next time. After my second play, I immediately looked up whether expansions were planned, because I want more Luthier! It’s a musical performance I’ll gladly revisit every time it hits the stage, not just for the stunning production, but for the tactical puzzle that satisfies every time. It showcases Dave Beck’s growth as a designer from his first title, and I’ll happily welcome all his encore performances.