Hello and welcome to ‘Focused on Feld’. In this series of reviews, I am working my way backwards through Stefan Feld’s entire catalogue. Over the years, I have hunted down and collected every title he has ever put out. Needless to say, I’m a fan of his work. I’m such a fan, in fact, that when I noticed there were no active Stefan Feld fan groups on Facebook, I created one of my own.

Today we’re going to talk about 2022’s Hamburg, his 33rd game.

A reimplementation of the Feld classic Bruges, Hamburg is the first game in Queen Games’s Stefan Feld City Collection (SFCC). Stefan Feld isn’t new to rebooting his games. Back in 2016, he created Jórvík, a retheme of his previous title The Speicherstadt. Those two games are so much alike that when I reviewed them, I simply lumped them together into a single review.

But Hamburg is more than just a retheme. Yes, there’s a new skin, but the entire game has been revisited and reworked. Some old things have changed. Some things are almost exactly the same. And there’s even some new content to boot. This review isn’t going into the particulars of how the game is played. You can refer to my review of Bruges if you need a refresher.

No, in this review I am going to focus on those things I mentioned earlier. What’s Changed? And What’s New? If you’re already familiar with the answers to these questions and just want to know what I think, feel free to skip ahead to the Thoughts section. Otherwise, let’s dive in and discuss Hamburg, shall we?

The Basics

Unlike Bruges which is played over an indeterminate number of rounds, Hamburg is played for exactly eight. The round structure is the same as it is in Bruges. The players draw back up to five cards in hand. Then the dice are rolled. Disaster levels increase (or not). Players have the option to move up the central track on the main board by paying money equal to the combined values of the dice showing one or two pips. Actions are performed. Majorities are checked. Rinse and repeat.

If that’s all there was to Hamburg, I’d treat it the way I treated Jórvík and The Speicherstadt. But there are some key differences that make Hamburg stand out as (SPOILER) the clearly superior game when the two are compared side by side. So, let’s talk about those differences.

What’s New?

The most visible difference is the game’s theme. Bruges was more about attracting denizens to the titular city you’d already built and finding homes for those folks. Hamburg is about the evolution of the titular city itself via the construction of buildings. Functionally, Hamburg’s buildings are stand-ins for Bruge’s people. This shift in focus necessitated a complete overhaul of the artwork, a shift which was met with some controversy. The artwork presented in the original Kickstarter campaign is very different from the artwork that’s present in the game now and that change rubbed some people the wrong way. I was among those disgruntled masses initially, but the new artwork has grown on me.

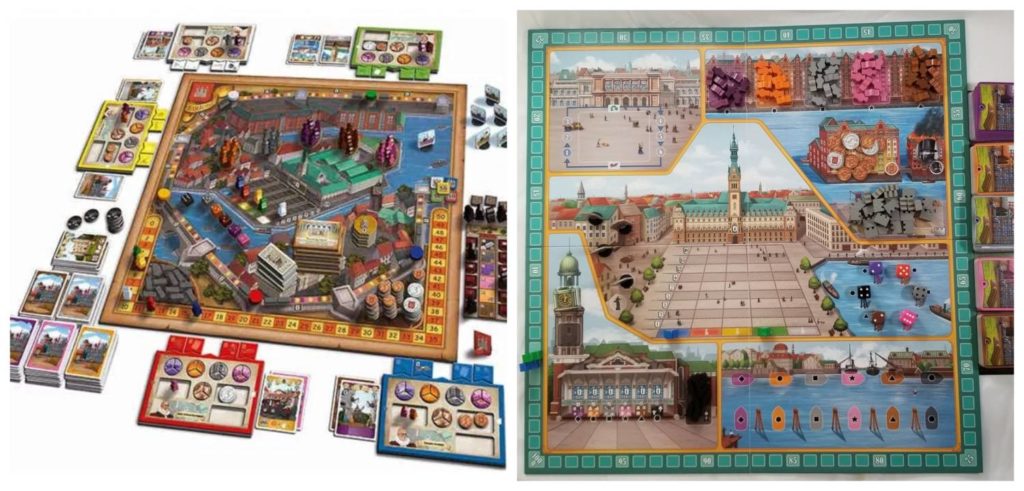

Additionally, Hamburg includes player boards where Bruges did not. These double-layered boards feature recessed locations for each player’s walls (which replace the old canals), majority markers, and disaster tokens. Gone are the pie-slice disaster tokens of yesteryear. These have been replaced by several square tokens that slide on a recessed track. Once they all slide over, the disaster occurs. There are even storage locations for the various workers a player might acquire.

In addition to the lineup of colors that correspond to the card, worker, and disaster colors, Hamburg also introduces a new die color: black. When a black die rolls up as a five or a six, each player must collect an Intrigue token (yet another new feature). Each Intrigue token has a single matching twin and displays one of the disasters. A player holding an Intrigue token must raise the matching disaster level by one before discarding the token. The black die serves a second function which I’ll cover in the next section.

The game also comes with six modules that can be added in to spice things up a bit. Two of these, The Ships and The Stock Exchange may seem familiar to anyone that’s ever played the Bruges: City on the Zwinn expansion. The other four—The Mayors, Hans Hummel and the Zitronenjette, Special Intrigue, and The Cleric Tiles—are brand new.

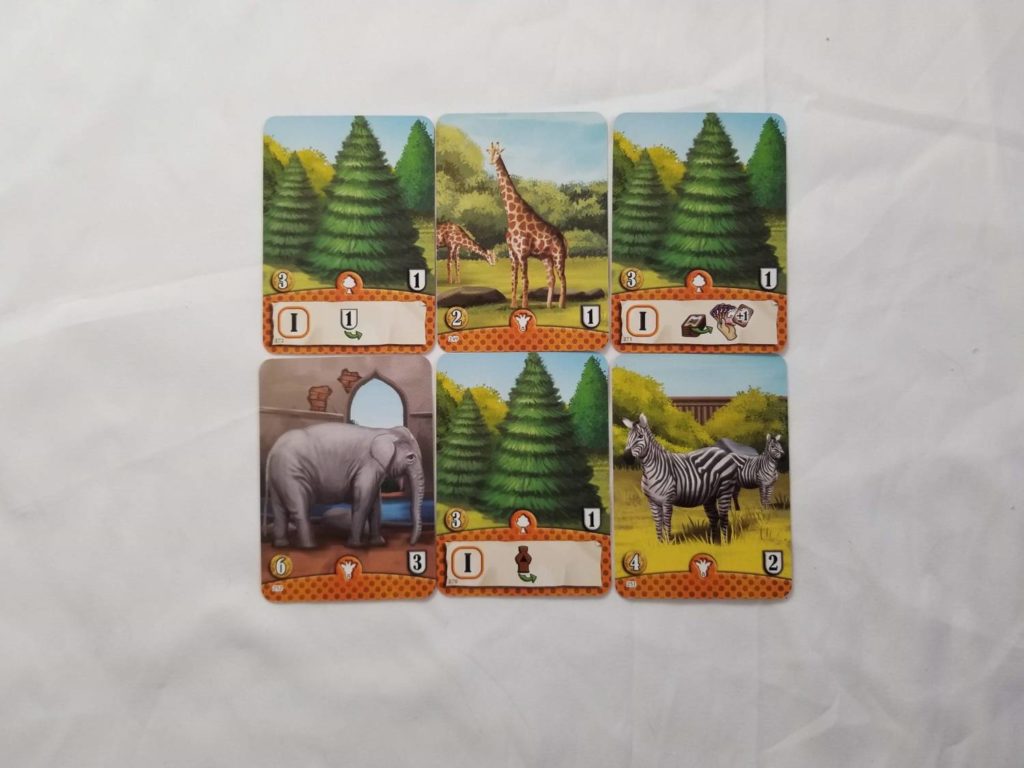

Lastly, Hamburg introduces two new card types: parks and zoos. These cards can be put directly into play without having to have played some other card first. Parks will reward their owners with some sort of benefit during the card drawing step at the start of each round. Zoos provide no benefit beyond the points shown on the cards. However, zoos and parks collectively count towards one of the new majority types which scores a player points at the end of the game if they’re able to flip it over before the game ends. The other new majority type rewards a player if they are ahead of everyone else on the score track when it comes time to score majorities. It’s also worth mentioning here that the card size has increased and all of the cards feature a lovely linen finish.

What’s Changed?

The setup for Bruges involved shuffling all of the cards together, breaking the deck apart into relatively even piles, assigning some of these piles to the cardholders, and setting the others off to the side. This convoluted process served not only as the game’s method for dispensing cards, but also served as the game’s timer. It’s also the greatest source of contention for Bruge’s detractors. The random cards drawn from the randomly shuffled decks made planning and strategizing almost impossible. If you hoped to build a red canal section, for instance, then you had to hope and pray that a red card would come up in the course of your draw up at the start of the round.

Hamburg has greatly simplified things in this regard. Each card color now comprises its own deck. Each of these are shuffled and kept separate. Not only does this make setup easier, but if you need a specific color to construct that next wall segment, you can guarantee you’ll have the color that you need. A welcome dose of strategy in an otherwise luck-driven game.

Houses, now called construction sites, are no longer worth points at the end of the game. Also, the act of trading cards for workers rewards you with three workers of the matching color instead of the two you’d receive in Bruges.

The final change is related to the aforementioned black die. Each time the black die is rolled, one of the priest pawns is added to the matching column of St. Michael’s Church on the main board. Each of these columns is associated with a specific card type. At the end of the game, each building a player has constructed of a specific type is worth not only the points printed on the card, but is also worth an additional point per priest in that card type’s column. There are only eight of these priests and the game ends at the end of the round in which the eighth is added to the Church.

Thoughts

When I first heard about the Stefan Feld City Collection, I’ll admit it: the idea was anathema to me. Why would I want to own revamped versions of games that were already perfectly fine? Bruges is pretty great. So why mess with it? And what’s wrong with Macao? As a self-certified Feld freak, I couldn’t see the point. In my mind, the whole thing just felt like a thinly veiled cash grab on the part of Queen Games (QG). Without even knowing why, I was angry. I was ready to write a stern letter.

But then I learned a crucial piece of information: none of these redesigns and rethemes were being done by Queen Games. They were being done by Stefan Feld himself.

Surely, if Feld took a look at his lovely creations and thought they could be better, didn’t I owe it to him to trust his reasoning and give these new versions a try? And, as a collector, shouldn’t I own my own copies of these games? So, I made up my mind. I decided I’d give the SFCC a chance. Maybe I’d been wrong.

Suffice to say, having played Hamburg now, I’m glad that I didn’t go with my original instincts. When comparing Bruges and Hamburg, in my opinion, Hamburg is clearly the better game. So much so, in fact, that I will probably never play my physical copy of Bruges ever again. Bruges, for all its glory, is not without its faults—and some of those faults are pretty egregious and hard to overlook. I touched upon them in my review, but here’s a quick recap: Bruges heavily relies upon luck with almost no way of mitigating it, the setup is convoluted, many people find it aesthetically unappealing, and there are some issues with the way that the mechanics mesh with the theme. Hamburg addresses all of these (and even an issue I hadn’t realized was an issue with Bruges until playing Hamburg), some with more success than others.

Before I jump into Hamburg’s successes, though, let’s talk about the (very) few ways that it misfires.

The Cons

For starters, there’s the language independence. The concept of language independence is nothing new. Instead of having a lot of text, a game will make heavy use of iconography instead. The idea is that anybody should be able to look at this symbology and understand its meaning without the need for text. It’s sort of like what Charles Bliss hoped to achieve with his Blisssymbolics. And, it makes sense. Aside from the obvious accessibility benefits, it saves publishers a lot of money. Instead of having to manufacture card sets in eleven different languages, the same cards can be used across every copy of the game. The only thing that’s needed is a rule book in the appropriate language. And then, theoretically, those savings are passed along to the consumer. It’s a win-win for everyone.

Or is it?

Hamburg stands as an excellent case study in overdoing it. There’s so much symbology that there’s an entire sixteen page Addendum devoted to translating the cards. It’s a bit much. And seeing as how there’s only one of these Addendums provided in the box, it can become particularly troublesome and time-consuming as the players are constantly having to pass it back and forth, especially in a two-player game where there’s less downtime between each of your turns. Thankfully, the cards are numbered and the Addendum further separates them by color, so you can typically find what you’re looking for quickly. I just wish the iconography were a little more intuitive and that another copy of the Addendum had been included. I haven’t ever given serious thought to printing out additional copies of materials that are already included in the box, but I’m seriously considering it for this game.

Maybe the global board gaming community needs to come together and develop a universal language of iconography for common game-related concepts. Then all any gamer would need would be a single dictionary and publishers wouldn’t have to bother with a separate Addendum for each and every game. Wouldn’t that be something? (But, I digress. Back to Hamburg now!)

Another, smaller, issue is the new Intrigue tokens. Bruges can be pretty brutal. On top of the constant hoping-and-praying one does during the game, there’s always the lingering threat of disasters hanging over your head. So, there’s a constant need to try to stave these off or at least plan for them so you’re not as adversely affected when one of them inevitably pops up to throw a wrench into the proverbial works.

I guess Stefan Feld felt like things weren’t brutal enough, so he added in the Intrigue tokens. Now, disasters come at you even faster. I’m not sure why Feld decided the game needed this. I assume it was because something needed to happen when the new die color was rolled as a five or a six to keep it in line with the other colored dice, and this is what he came up with. My question is: why? Why couldn’t the die have been added specifically for the purpose of adding priests to the Church and nothing else? It just feels like this aspect of the game is entirely unnecessary. Even the addition of the third module—Special Intrigue—doesn’t make it make sense. If anything, that module only serves to make it even worse—most of these Special Intrigue tokens force you to go up on multiple disaster tracks. If you’re asking me, I’d just advise you to remove the Intrigue tokens entirely. They’re really not needed. Their only purpose is to inject more misery into the game and why would you want to subject yourself to that?

The Pros

Earlier, I mentioned Bruges’s aesthetics. Back in its heyday, maybe those graphics and illustrations would have felt like they were top of the line. But, by today’s standards, they’re pretty unsightly. Visually, everything about that game has a dark, heavy feel about it. Not to mention its overall “beige-ness”. There are people like me that like this sort of thing, but the vocal majority these days take one look at Bruges and write it off as an ugly, boring euro. Suffice to say, Bruges’s aesthetic isn’t doing it any favors.

Hamburg is a whole other story. Its illustrations are bright and vibrant. The choice to keep the players’ game play on their player boards instead of clustering it all on the main game board (as in Bruges) was inspired. It allows the artwork—and by extension, the players—room to breathe. There’s still a great deal of action happening, but it feels less crowded. It may be a form of synesthesia, but this openness makes the game feel lighter and more inviting, like playing in a park as opposed to playing in a cramped basement storage room. And that’s important.

And before I move away from aesthetics, I’d like to point out one other thing. One of the other side effects of Bruges’s swampy exterior was that its usage of similar dark tones and primary color pieces created an environment that unintentionally excluded a large portion of its potential playerbase. This is thankfully addressed in Hamburg.

Queen Games has really put a lot of effort into making Hamburg as colorblind friendly as possible. Gone are the standard primary colors—blue, yellow, red—and our old friend, green. These have been replaced by purple, orange, grey, and pink. That’s a good first step. But QG has taken the extra step of assigning each color its own special symbol as well. These symbols even appear in the background of the faces of each of the cards.

As mentioned earlier, when QG initially announced their intention to change up the artwork mid-campaign, I was not thrilled. I was in love with Bruges and the new game board for Hamburg closely resembled the game I’d come to know and love. Naturally, I loved what was originally proposed for Hamburg. When QG said they were going to change that, I wasn’t ready. But now that I’ve experienced it, it’s hard for me to look at Bruges (or the original proposition for the Hamburg game board) and see anything exceedingly positive about its appearance. It serves the game well, but having seen how things can be better, it’s difficult to look backward and pretend I don’t have that knowledge. If anything, these past couple of decades that I’ve been into the hobby have taught me that not every gamer is alike and that more times than I know, the person sitting across from me is going through a struggle that I can never understand without experiencing it for myself. And for people like that, it pleases me to know that games like Hamburg exist.

In my review of Bruges, I also brought up some thematic issues that I found peculiar, like a princess agreeing to live in some hovel that I built for her next door to another hovel that I built for a dog. Then again, maybe it was some sort of medieval Gunther’s Millions situation (look it up!). If that’s the case, I guess it would make sense if you squint your eyes a bit and look at it from just the right angle. Fortunately, Hamburg doesn’t require any mental gymnastics to make the theme fit. Instead of turning your cards into houses, you’re turning them into building sites. And, instead of placing people into the homes you’ve built, you’re constructing buildings onto the sites you’ve got laid out. It all makes sense, and I like that.

I also like the way that the black die and the priests combine to form the game’s timer. What I especially appreciate about this medley is the emergent scoring conditions that result from it. Knowing that each “x-type” of building you have at the end of the game is going to be worth additional points gives you a guidepost to work towards in an otherwise open landscape of possibilities. Having a clear path to follow has never been a bad thing. It’s also helpful to know exactly when the game is going to end. Bruges’s ending was always a bit of a question mark. Would your opponent draw the last card from Deck B to trigger the end game, or would they draw a little from both decks to keep it going? It made it difficult to plan. The knowledge that “this is definitely the last round of the game” ensures you’ve got the notice needed to know it’s okay to go nuts and try to eke out as many final points as possible, a risky move in Bruges that might come back to bite you.

But the thing I like best about Hamburg is that each color has its own separate deck. Bruges involved a lot of hand wringing and supplication. You were largely at the mercy of the board game pantheon. Need a purple card to build that canal? Better pray you draw one. Need a red card to get rid of that threat? Better pray you draw one. Need a blue card so you can get the workers needed to activate that other card? Well… you know where this is going.

In Hamburg, though, while you’re still at the mercy of the heavenly hosts when it comes to the actual content of the cards you’re drawing, you can at least control the color. That makes all the difference. Whereas Bruges often left you feeling like the game was playing you, Hamburg puts you, while not exactly in the driver’s seat, at least in the navigator’s chair. That’s a sight better than riding in the bed of the truck.

As I stated earlier, Hamburg has replaced Bruges for me. While I’ll always have a fondness for its predecessor, Hamburg is my new fling. It’s time for me to put that past relationship in my rearview.

Would I recommend you do the same? Well, that depends on a few different factors. Do you own Bruges already? If not, Hamburg’s the way to go. Not only is it going to be a lot cheaper to obtain, but you’ll also have the benefit of enjoying Bruge’s expansion content without having to also track that down. If you already own Bruges, do you also own its expansion? If so, Hamburg’s probably not going to give enough of a different experience to justify the purchase. If you already own Bruges, are you a Feld completionist like myself? If so, then it goes without saying that you’ll definitely want to add Hamburg to your collection. I’m glad I added it to mine.

Bruges will always have a place in my collection, but Hamburg will always have a place on my table.

Add Comment