Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

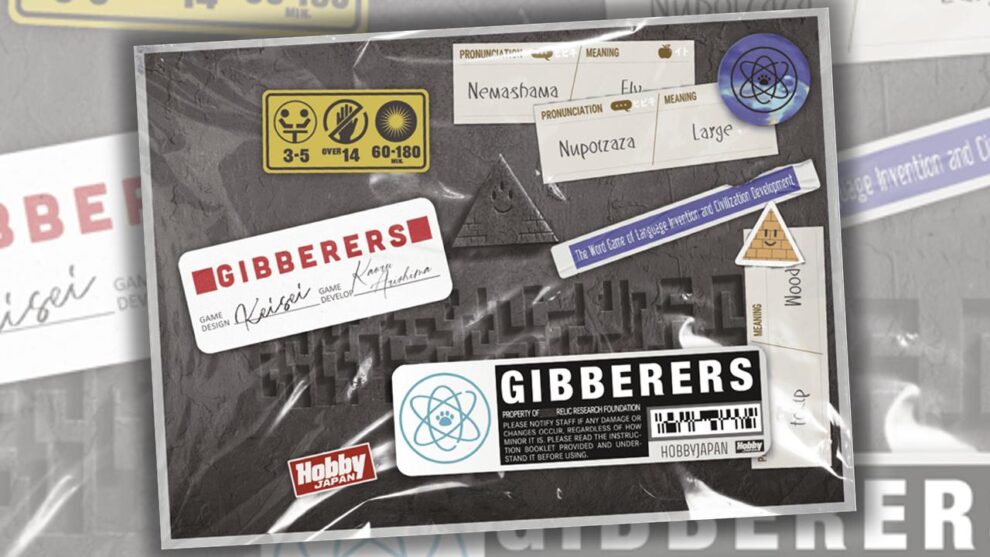

Gibberers, a language creation game from designer Keisei and publisher Hobby Japan, is full of interactions like this:

After a moment’s hesitation, Khari put the card down and picked up a pencil. “Queesys,” she said, as she wrote out the word.

“Queesys,” we all repeated.

She paused, surveying the options within our limited lexicon.

“People have money. A few people have a lot of money.”

“Okay.”

“But many people don’t have money. Many people don’t like that a few people have a lot of money.”

Ryall held up his hand. “Many people want money?”

Khari wobbled her head back and forth in uncertainty.

“Yeeeeeeees, but… but no. Many people don’t want money.”

“Hrm.”

Andrew (no relation) hazarded a question. “‘Queesys’ is an idea?”

“No, ‘queesys’ isn’t an idea, ‘queesys’ is an action.”

Ryall’s eyes lit up. “People have money, but many people don’t have money. Many people do a ‘queesys’?”

“Yes!”

“I know! ‘Revolution?’”

“Yes!”

Everyone cheered.

While that interaction may not seem worth relating, a little stilted and a little strange, it is important for you to know that it is a translation rather than a transcription. If you were in the room at the time and you hadn’t been playing Gibberers, that interaction would have sounded like this:

“Queesys,” she said, as she wrote out the word.

“Queesys,” we all repeated.

She paused.

“Jubjub deek eepu. Zib susu jubjub deek susu eepu.”

“Pahd.”

“Lay susu jubjub zib deek eepu. Susu jubjub zib brzk jubjub deek susu eepu.”

Ryall held up his hand. “Susu jubjub kokee eepu?”

“Paaaaaahd, lay… lay zib. Susu jubjub zib reek eepu.”

“Hrm.”

Andrew (no relation) hazarded a question. “Queesys kubu?”

“Zib, queesys zib kubu, queesys pokubeekach.”

Ryall’s eyes lit up. “Jubjub deek susu eepu, lay susu jubjub zib deek eepu. Susu jubjub doozk queesys?”

“Pahd!”

“Yom deek! ‘Revolution?’”

“Pahd!”

To quote my friend George, who was sitting at a table nearby: “As you’ve all been playing this for the last three hours, I’ve felt like I was having a stroke.”

For the players, it all made sense. Everything we said came from the language we’d been building. What started as a collection of 18 words had, by the end of the night, grown to include nearly 50. For four hours—there is a 60-minute rule set included as well—we spoke almost nothing but the language we called Jubjub. In that time, there was confusion, there was frustration, there were breakthroughs, and there was near-constant laughter.

Lexicon and On and On and On

The first step of the game is to name your language, then create its first 18 words. The initial vocabulary must include “yes,” “no,” “I,” and “know,” but the rest are up to you. One of the more marvelous things about Gibberers is that it leaves vast amounts of space for player creativity and self expression. That’s true from the jump. The communal creation of those first 18 words tells you a lot about the players, as they talk about the things they assume and believe to be most fundamental to communication and life.

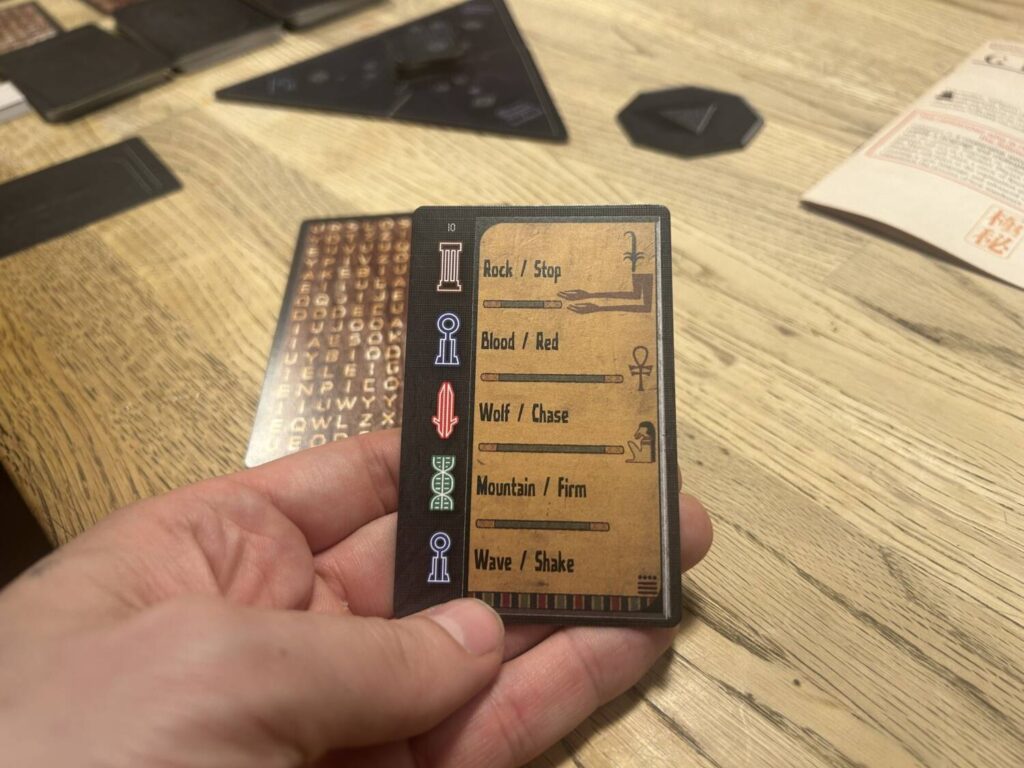

Each word is written on a slip of paper, along with its English equivalent, and placed on the table under the appropriate alphabetical tab. Words are sorted by their first letter in the new language rather than English, which I initially found confusing, but within a few rounds I understood. It slows the speaker down a bit, while making it easier for the listeners to keep up. If you say a word I don’t remember, I can follow my ears straight to the definition.

Once the starting words are done, the rest of the game is spent taking turns as the active player, who draws a card, chooses a word, and attempts to describe that word to the other players. The early rounds feature words with paired meanings: the same word denotes both “Water” and “Invisible,” or “Banana/Many.” It helps to introduce more flexibility into the early game, and teaches the players an approach that is key to the game’s success. I’ll come back to that in a moment.

Each new word, once guessed, gets added to the dictionary. As you go on, of course, the words get more and more complicated. Early words become cornerstones of your vocabulary, referenced all the time. That’s not so much the case in the last few rounds. We didn’t get a ton of post-facto usage out of “xixi,” the word for “marketing.”

Jubjub Zib Deek

Another remarkable thing about Gibberers: it is as close as I think a relatively concise game will ever get to depicting the natural evolution of a real language over time. Language development in real life is a wild and unkempt thing. It takes time, repetition, compounded errors, neighbors to borrow from, and emergent technologies to fashion a language as we know it. The words in Gibberers have defined meanings, but there’s no rule that says you can’t start to use them in other ways. “Kubeekach” started out as “real/true,” but we quickly found that we needed a word for “thing,” and “kubeekach” naturally took on that function. Our starting set didn’t include a word for “to have,” and the first player needed “have” right off the bat, so Jubjub made much poetic use of “deek,” the verb “to know.” We never developed an independent word for “to possess” or “to have.” We were able to distinguish “deek”s from the context.

Not everybody is going to always pick up on that kind of thing. A moment of great frustration for me as a player came when another player used one of our invaluable hint tokens to add the word “eebi,” “currency,” to a lexicon that already included “eepu,” “jewels.” To my mind, that was redundant, though I will gratefully acknowledge that Zin did choose to give the two words a shared etymology.

To that end, another aspect of language that Gibberers does a strangely good job of emulating is the development of a syllabary, of the phonetics, even of etymological word groupings. Because each player, in turn, adds a word of their own imagining, patterns of sound preference start to emerge. I like soft “j”s and “k”s—the French word for sea shell, “coquillage,” may be my favorite contained auditory experience in any language. My word additions were full of those sounds. Khari favored lengthy vowel groupings. Taken as a whole, it was as though each player’s contributions came from a different branch of the tree. My addition of “brzk,” “to enjoy,” proved an abortive attempt at adding the rolled r to the language. The sound left the language because it was too difficult, as often happens. “Brzk” sat there as a remnant of a long-forgotten forebear.

The last thing I can think of for the moment that makes Gibberers remarkable is the degree to which it involves its players. I have rarely felt as present and absorbed and engaged by something as I did this game. There were times when the words would stop making sense and I would let my mind wander, but at five players, you can do that. We all took turns tuning out for a bit, letting the language wash over us. You are never not thinking while playing Gibberers, never not making connections and having ideas and postulating guesses and making sudden realizations. For four hours on a weeknight, with five players whose brains are fried by the constant stimulation overload of living in New York City, I don’t think I saw a phone come out more than ten times total.

When I showed the opening transcription of this review to Ryall the other day, he said, “the worst part is, I can still read and understand all of it.” We played the game over a month ago. Gibberers is not just about language on a surface level. It is about the things that make language spectacular. It is about sounds and meaning and connection and creation. All that in this tiny little box. Gibberers is a wonder.