Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

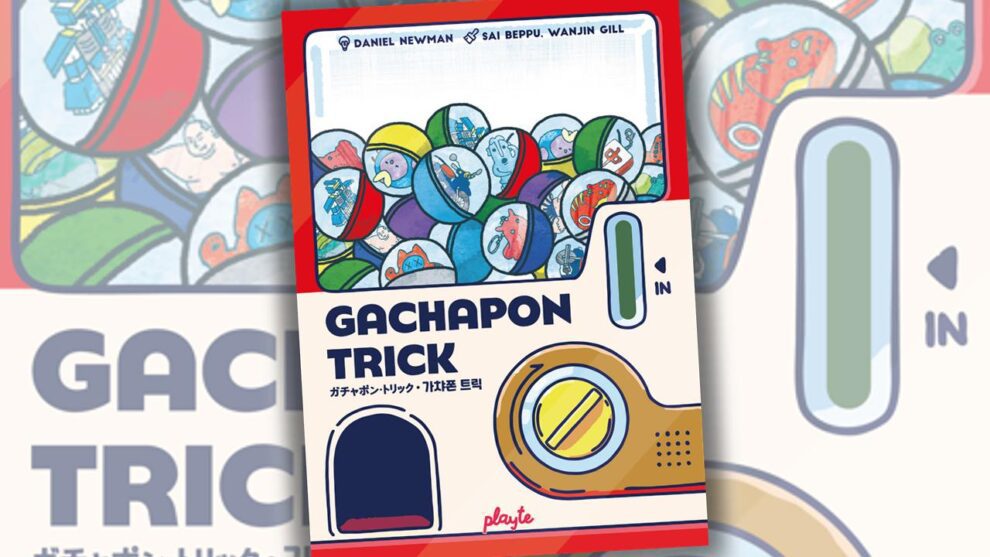

Ga•cha•pon (ga cha pon) n. capsule toy dispensed from a vending machine, particularly popular in Japan.

1960s; Japanese, onomatopoeic origins.

You’re probably familiar with Gachapon, even if you don’t know you’re familiar. They’re those small plastic toys sold in vending machines, the ones that come in plastic capsules. In Japan, these bringers of joy and delight and the slightest rush of endorphins can be found all over the place. There are entire aisles and stores of them. For just a few Yen, you too can try your hand at bringing home a Doraemon keychain.

It’s the thrill of the chase that drives Gachapon sales, much as it drives the sale of blind boxes here in the U.S. (Japan is no slouch in that regard either). It’s fitting then that Gachapon Trick, from designer and publisher Daniel Newman, is centered around both trick-taking and set collection.

The tricks play out about as you’d expect. Everyone has to follow the lead suit if they can, but the winner isn’t the player with the highest card in the suit. Thank god for that. Gachapon Tricks has seven suits with seven cards each, and only 3/4 or so of the deck gets dealt out every hand. The lead player would just about always walk away with it. Instead, the winner is whichever player plays the highest card in the most-represented suit, or, as often ends up being the case, whichever player played the out-and-out highest card in the event that no two cards match.

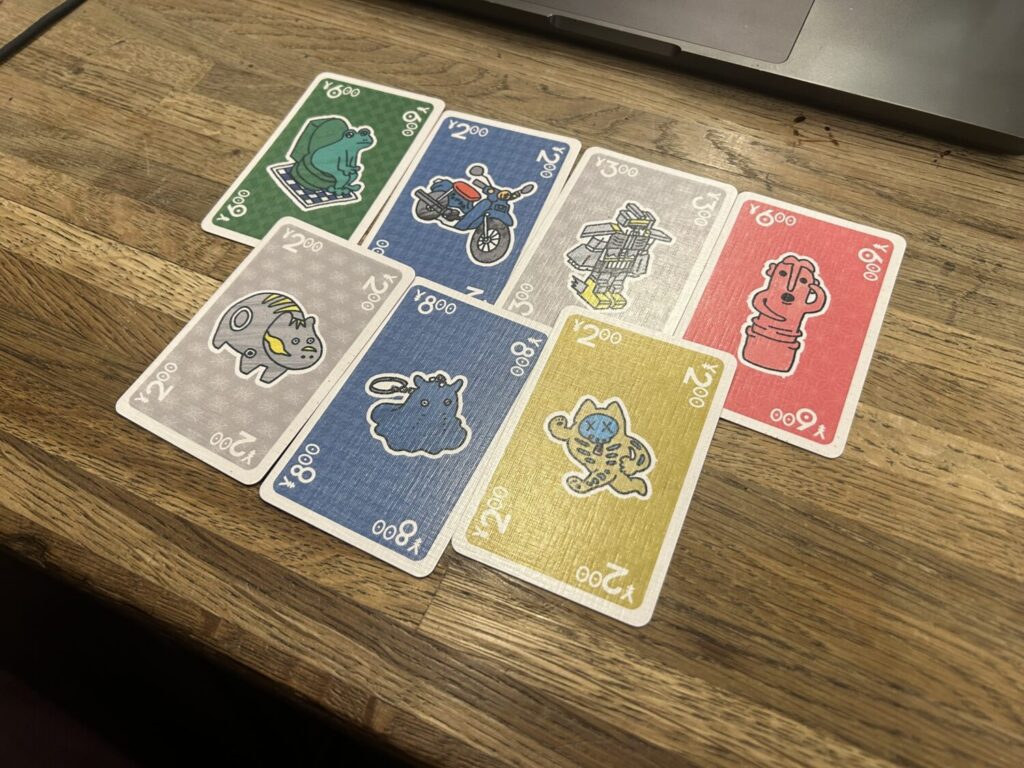

Tricks themselves aren’t worth much, but a win affords you the opportunity to spend some of the ¥5000 burning a whole in your pocket on cards that were played into the trick. Your goal is to collect large sets of the hippos, ghosts, toilet frogs, robots, cacti, x-ray cats, and motorcycles that populate the deck. A narrow focus and commitment of resources will serve you well, assuming you’re ever in the position to leverage either. One of the problems with Gachapon is that a bad hand affords you little opportunity to participate in the central scoring mechanic.

Tricks themselves aren’t worth much, but a win affords you the opportunity to spend some of the ¥5000 burning a whole in your pocket on cards that were played into the trick. Your goal is to collect large sets of the hippos, ghosts, toilet frogs, robots, cacti, x-ray cats, and motorcycles that populate the deck. A narrow focus and commitment of resources will serve you well, assuming you’re ever in the position to leverage either. One of the problems with Gachapon is that a bad hand affords you little opportunity to participate in the central scoring mechanic.

The titular gimmick, on the other hand, is a blast. The winner of each trick may spend ¥500 to reveal the top card of the deck. It is a rare thing in a game that you find yourself rooting for your opponents, but you can’t help but find yourself allied with your opponents against the odds when they decide to turn the handle. Occasionally, the card you draw costs more than ¥500 you pay. Most of the time, it doesn’t. Occasionally, it’s part of a set you’re already trying to collect. Most of the time, it isn’t. But when either or both of those align, Gachapon Trick moves the entire table to cheer.

The thrill of those pulls and the degree to which Newman has successfully replicated the push-your-luck rush of low-stakes gambling does translate into weaknesses as a trick-taker. You can’t play with much intentionality unless you are leading an early trick or closing out a mid-to-late one. Games like Seas of Strife make a virtue out of that murkiness and uncertainty, but Seas of Strife isn’t a set collection game. Because the tricks in Gachapon Trick are a means to an end, you lack nearly all agency without the right hand. Players who don’t buy anything the whole round do end up with a buttload of points, but that doesn’t mean they have a good time.

There aren’t many trick-taking games that manage to feel thematic. They tend towards the abstract, pure experiments in table dynamics. Gachapon Trick individuates itself by evoking a place, an action, and a mindset, the feeling of ripping open blind boxes or chucking in another coin and cranking the handle in sweaty desperation. That doesn’t quite make up for what it lacks as an experience, but it is certainly a worthwhile experiment.