Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

At some point, a schism formed within the Church of Our Mother of the Board. There were those who believed in cold, calculable numbers, in the beauty of efficiency and a ruthless system, and those who believed in the unpredictable joys of interactivity. For many years, they had coexisted peacefully, but no more. Those who prayed at the altar of the numbers could not abide their calculations being interrupted by the capriciousness of player choices. Those who believed in the absolute supremacy of social interaction did not want to add, subtract, or, Our Mother forbid, multiply.

In the times before that schism, there were many games that managed to thread these ideas together, such as those drawn from the scriptures preached by a monk known as Knizia. Here was a master of welding the cold and calculable to the interactive, a man who seemed to understand how to make addition, subtraction, and even the dreaded multiplication fun. His teachings, the books of Lost Cities and Modern Art, were both mathematically and socially ruthless. Coexistence was possible. Then we lost the way.

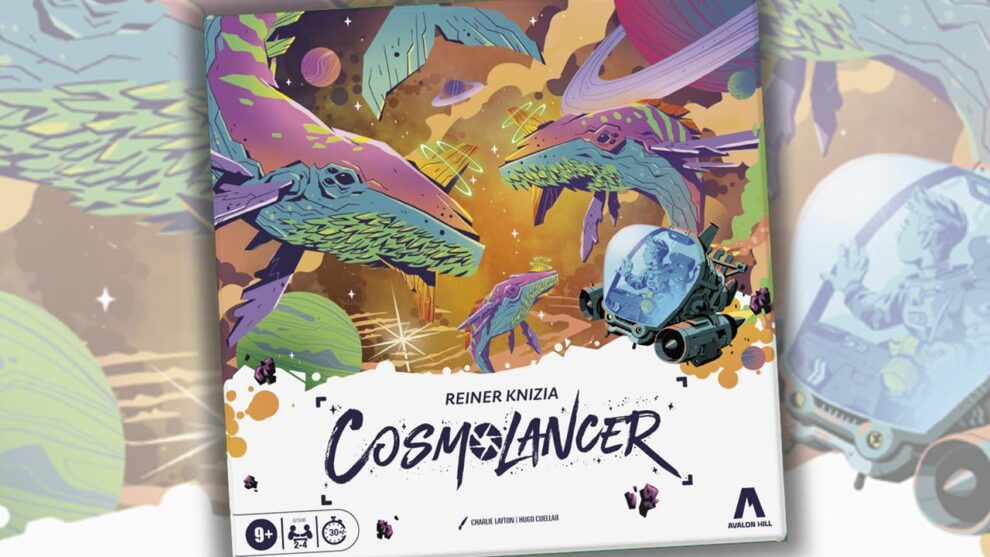

Space Whales! Whales! In Space!

Amongst the many games Reiner Knizia published in the mid-90s was Auf Heller und Pfennig (To the Last Penny), which you might know better as Kingdoms, and can now find as Cosmolancer. It’s a simple tile-laying game, quick and enjoyable. No matter the edition, theme is not one of Cosmolancer’s strengths, so I won’t be bothering with explaining it in those terms.

You have three actions available to you on your turn, though they’re all effectively the same thing: place a tile. It might be a tile from the supply, or it might be one of your player tiles. Most of the supply tiles are worth positive or negative points. The player tiles score you points for the row and column in which they are placed, multiplying the value of each by somewhere between 1 and 4.

The trick here is that player tiles multiply the total value no matter what that total value is, and you bet your buttons that those rows and columns can end up being worth negative points. Depending on your group, Cosmolancer can be a very aggressive game. Stake out your claim too early, and everyone will dump negative tiles into your territory. Stake your claim too late, and there likely won’t be any good spaces left.

To give the whole thing a patina of planning ahead, each player gets one supply tile at the start of the round. Placing it is the third action available to you. While having one pocket tile may not seem like much, it gives you more to go on than you’d think. The special tiles can do things like split a row or column in half, protecting you from negative points or cutting off your opponents from fulsome point sources. Your higher multiplier tiles don’t come back at the end of the round. They’re one-and-done. Someone keeping you from getting your money’s worth can be devastating.

The Way

Cosmolancer isn’t a great game, by any means. It’s good. It’s solid. You play for thirty or forty minutes, you swear at each other, one of you wins, then you pack up and move on. It is, however, reliable. You will swear at each other. The game will wrap up in less than 45 minutes. It’s also easy enough to teach that anyone can play. There’s a lot to be said for all that.

I keep thinking about how unusual it feels now, how out of time designs like this are. The mathy games, by and large, have bloated into larger, ungainly systems. The shorter games, even those that are in fact math-intensive, do their best to mask it. We don’t get games like Cosmolancer anymore, games like Lost Cities, those tiny and quick boxes that were a dime a dozen in the mid-90’s. Don’t hide your math under a bushel, designers of lighter games. Let that freak flag fly.