Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

At last year’s Festival International des Jeux in Cannes, France, I had the chance to meet the designer of Colt Express, Christophe Raimbault. Not only was it a lovely conversation, but it was a lovely conversation in English, one of the very few conversations in my native language I had during my four days at that show.

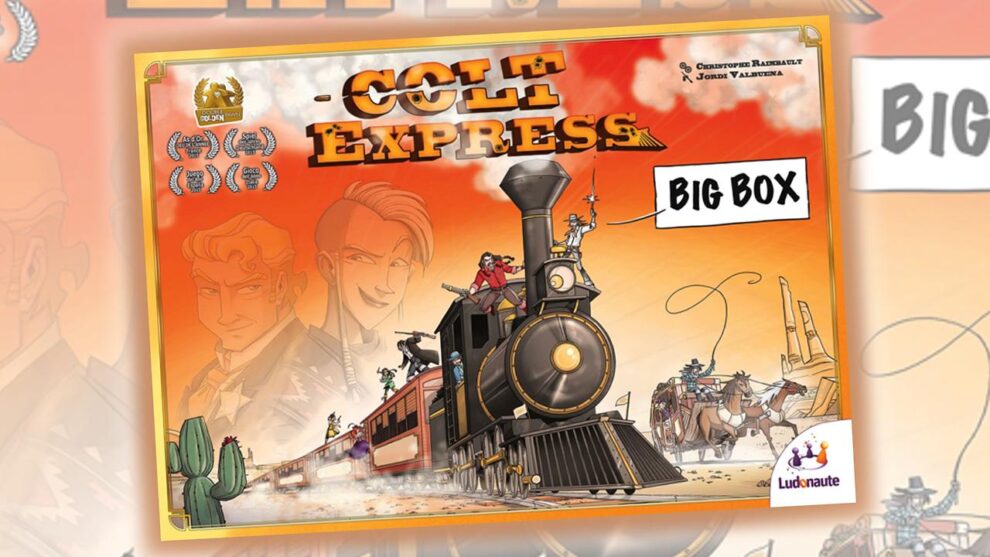

Certainly, Raimbault has designed other games, the most recent being Redwood, a game glowingly reviewed by my colleague Bob Pazehoski, Jr. last year. But there’s no question that Colt Express—a game first published in 2014, with a 10-year anniversary box made available last year at SPIEL in Essen, Germany—has had the biggest impact. Colt Express won the 2015 Spiel des Jahres (beating out fellow finalists Machi Koro and The Game), joining the ranks of fun, light classics such as Azul, Dominion, and last year’s SdJ winner, Sky Team. Colt Express has sold millions of copies and led to the publication of the Colt Express Big Box, a chance to get all those Colt Express goodies in one box.

The team at Flat River Group sent a review copy of Colt Express Big Box, so over the course of about six weeks, I used Colt Express as the filler for my review group sessions. (I also squeezed in two plays on Board Game Arena, to refresh myself on the gameplay.) In this way, we could play the game a lot while also slowly implementing expansion content into each play.

We hadn’t previously published a review of Colt Express here at Meeple Mountain, so this review is a combined discussion of the base game and everything in that very big—but surprisingly light—box.

Colt Express (The Base Game)

Colt Express is a programmed movement game. It’s not a game mechanic that I choose to incorporate into many game nights at Casa Bell; in fact, 1994’s RoboRally was my first exposure to games featuring turns where players secretly (or, in some cases, openly) plan actions then play cards to “program” the movement and actions of pieces on a board. After RoboRally, I didn’t find a lot of games—or a lot of interest—in tabling similar experiences, although Heat: Pedal to the Metal has earned many fans in one of my gaming circles.

Colt Express moves the action to an Old West playground and puts players in the boots of bandits trying to rob a train. Over the course of five rounds, players spend their turns playing one of the cards from their hand into a pile. These cards are all actions—punch another bandit, rob a civilian, shoot another bandit, switch cars or floors of the train.

The train is represented by a cute cardboard train that my large hands still hate, 10 years after I first tried the game with friends at a bar in the Logan Square area of Chicago. Here’s the deal with those action cards—when everyone has finished playing cards in a round, the entire deck is flipped over and executed in the order the cards were played.

Games of Colt Express immediately turn into chaos. That is simply going to work for you or it won’t. In my experience, strategy gamers typically struggle with the format. Even if you were somehow able to remember the action of each opponent in a full six-player game—which might be 30 cards or more—you probably didn’t fully comprehend how your own actions would interact with the other players.

Many turns end up being ridiculous. A player hoping to punch a bandit holding a “purse” or a gem punches air instead. Someone hoping to shoot the bandit Django when he was on the roof instead shoots a different bandit who has chosen to change floors, popping up right in front of their intended target. Everyone has a card that allows them to move the marshal figure—yes, even the cops have a hand in the proceedings—and it is possible that you just moved the marshal out of the locomotive car, creating an opportunity for an opponent to grab the $1,000 strongbox.

Et cetera. Colt Express is a programming game, but because it uses a whole-round-of-cards format instead of a turn-by-turn format, players often play cards just to see what happens.

That makes Colt Express family-friendly fare that lands much better as the kickoff to a casual game night with casual players, not the core hobbyists I usually game with. (Unless you are a member of my Wednesday night group, which somehow mixes games of Sausage Sizzle! and SETI: Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence with equal aplomb.) Most people understand that “winning” a game of Colt Express is often a matter of luck.

Luck, but with a heavy helping of strong, value-based production and the distinctive art style of Jordi Valbuena. The train cars are cute, easy to assemble, lightweight, and ready to be toppled by hands large and small. The meeples in the Big Box edition are great, and thanks to an assist from the Ludonaute marketing team last fall at SPIEL, I have the 10th Anniversary screen-printed meeples to swap in for the wooden standees. The Big Box insert features 16 lined compartments to keep the train cars and cards safe, so it’s easy to pick out what you need depending on the expansions you have in play.

My big question after 10+ years? Whether Colt Express has held up. That was a mixed bag.

On the one hand, I found Colt Express to work well with my family more than my review group. The review crew—generally, these are seasoned gamers who will play anything—enjoyed Colt Express but none of them was planning to run out and buy themselves a copy. In part, that’s because programming games have evolved since 2014. The aforementioned Heat: Pedal to the Metal, or other racing games such as Flamme Rouge, offer more flexibility to recover from some of the chaos of programming game elements, in a structure that does not commit all cards to an entire round’s worth of shenanigans. Newer programming games lean more into the programming as strategy elements, rather than tactical actions.

On the other hand, Colt Express brilliantly captures a moment in time. When it first came out, Colt Express was always on the table during our weekly game nights. It is always high comedy watching the actions play out. It’s a very flexible design, with six characters that have basically no learning curve—each bandit has a power that is so easy to remember you don’t even need a player aid, which you won’t hear me say…ever, nowadays—in a format that usually takes about 30-45 minutes to play.

You could “run it back” with Colt Express every night and not be worse for wear.

Colt Express: Horses & Stagecoach

The main additions offered by the first expansion, Horses & Stagecoach, start with the introduction of the “Horse Attack.” No, players don’t attack the train with their horses, they ride in during setup to give players the choice of which car to place their bandits. That also means we get cute wooden horse meeples that rest alongside the train and can be used by bandits to move around the train using a transportation method beyond the roof of the train.

The other big addition? A stagecoach which begins the game traveling alongside the Locomotive. This separate car can be boarded by the bandits during play. The Stagecoach has a $1,000 lockbox in the driver’s seat, guarded by the Shotgun (strangely, the Shotgun is a person, not a weapon he is holding). Like the Marshal from the base game, the Shotgun is a non-playable character that can be punched and forced to drop that lockbox to give players another way to score big cash.

When a bandit boards the Stagecoach (by either using a horse to ride into the Stagecoach, or jumping from the roof of the train to the roof of the Stagecoach), that bandit also has to take on a hostage which (usually) slows them down a bit with some sort of negative power for the remainder of the game. In exchange, each hostage is worth end-game cash to the associated bandit. Because there is one less hostage than the number of players, it’s a bit of a race to get a hostage early on, but the payout can sometimes be variable, so that helps mitigate the urgency.

Horses & Stagecoach has a couple new events plus the Ride action card to use horses to move around the train. But most of the core gameplay of the base game remains, thanks to the chaos engine that is Colt Express. (The best thing about Horses & Stagecoach is the addition of a new rule on some event cards that forces all players to reveal their action card at the same time, even though that card is still added to the played cards pile in turn order. That provided a little more drama when players were programming their turns.)

“I’m not sure I would play with this module again,” one player said after our first five-player game of Horses & Stagecoach, and that’s where I landed as well. The Stagecoach makes the main train less crowded. In one game, we had two of the game’s rounds take place where everyone took all their actions on the Stagecoach or the roof of the main train, leaving the Marshal to be little more than a nuisance that needed to be moved around when players used the associated action card.

Less crowded is bad, even if the chaos on the single-car Stagecoach did prove to be funny. The hostages are also wildly different, so while one pays handsomely and others might pay nothing (thanks to conditional language on certain hostage cards), this makes players think twice before rushing to the Stagecoach to grab a hostage if there’s not much in it for them. The Horse Attack setup step—badly titled, which I assume is tied to a translation issue from the game’s original French production—does shake up where everyone starts, but we found that it might also be slightly game-breaking. If the players in the first round are not able to move the Marshal towards other players, one might just start in the middle of the main train, then ride a horse to the Stagecoach to grab a juicy hostage bonus before other players can get there.

Horses and Stagecoach wasn’t bad, but the juice wasn’t worth the squeeze in my opinion when it comes to the additional rules overhead.

Colt Express: Marshal & Prisoners

The game’s second expansion made one thing clear as soon as I began reading its rulebook: Marshal & Prisoners is for a Colt Express superfan.

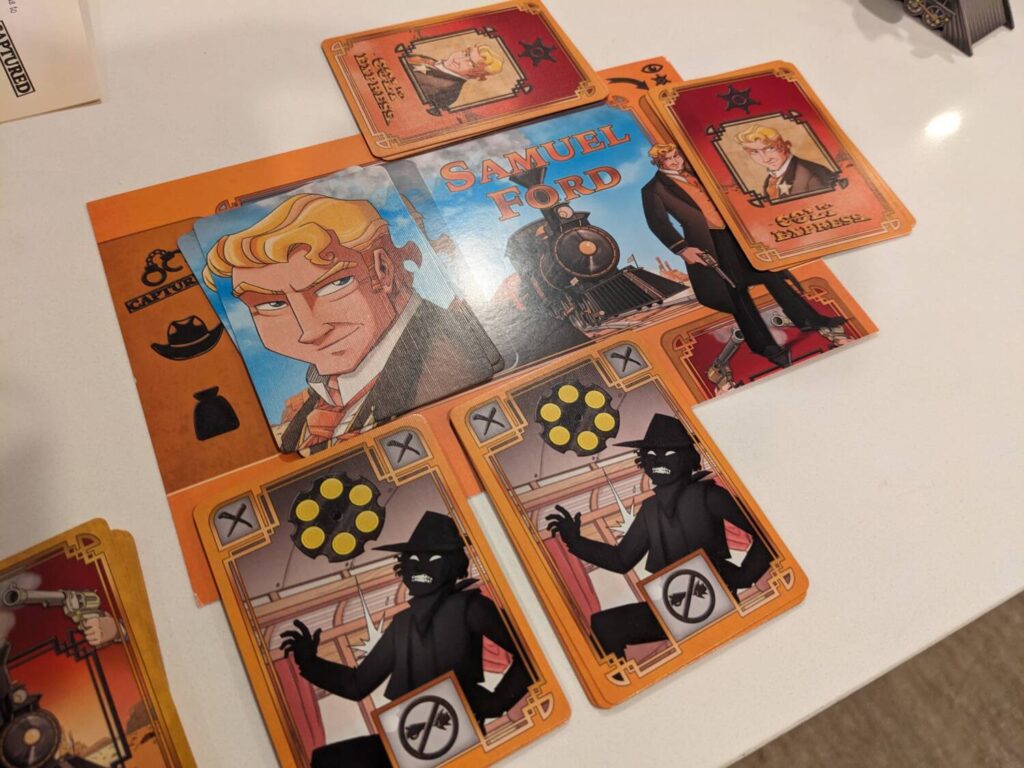

That’s not because of the rules overhead; in fact, like everything in the Colt Express Big Box, adding or subtracting extras is as simple as it is your availability to put everything on the table. No, Marshal & Prisoners is for a superfan because the person who loves the base game most should play as the Marshal, now a playable character in this final expansion.

Marshal Samuel Ford is assigned to one of the players, while everyone else takes on a bandit character as normal. (Mei, a new bandit addition for this module, is also available, and her special power allows her to move diagonally when she moves around the train, so she can keep things agile by choosing to either change cars horizontally or move to the roof with a move action.) The Marshal has a couple new tricks up his sleeve: he can’t punch anyone, but he is carrying two pistols instead of just one, meaning he has two decks that he can push through to add neutral bullet cards to a bandit’s deck.

The Marshal’s bullets seem to be laced with a weird poison, because when they “hit” a bandit, the wounded bandit is temporarily slowed by a negative effect for the rest of that round, based on symbols shown at the bottom of each Marshal bullet card. A bandit might get shot in the leg, so they can’t change floors, or maybe they can’t punch, loot, or shoot as an action for the rest of the round. That would be unlucky, since this is a programming game and a bandit might have played cards like that without knowing that they are now useless!!

The Marshal can also arrest bandits in this expansion, which moves a bandit to the rear of the train into a Prison car. This also awards the Marshal with a bandit’s Wanted card, worth cash at the end of the game, to the bandit if they are able to avoid arrest. Once they are in that cell, one would think that the cell would keep those pesky bandits out of action for a while. And that would be a mistake. In this expansion, bandits also have a “Brilliant Idea” card in their decks that, when played, squeeze them out of their prison cell as a normal action.

The main win condition is different here, thanks to a personal deck of goal cards held by the Marshal. If they can achieve four of their five personal goals by the time play ends, the Marshal wins the game. Otherwise, the bandit with the most loot wins as usual.

We liked Marshal & Prisoners more than Horses & Stagecoach, in part because there is a lot of potential for the playable Marshal to extend the life of a game for someone passionate about getting Colt Express to the table. Mei’s movement power is surprisingly effective to keep her in motion and out of the hands of the Marshal. There are now accomplices that can help a bandit once they visit the Prison car, either as an extra set of hands to grab loot or to adopt the power of another bandit. And making the Marshal playable also adds one extra big-value loot token for players to snatch.

Best Western

If you are a fan of the Colt Express base game but never got around to picking up the expansions, it’s worth a look to grab this big box of goodies, especially for the second expansion. The Big Box gives you a chance to play a game that now accommodates as many as nine players and that would greatly extend the playtime since I occasionally host nights with that many players, and Colt Express is a very simple teach featured in a beer-and-pretzels-style engagement.

My perfect mix is actually simple with this package—I’m sticking to the base game but using the two extra characters to give players more choices during setup, for game nights where I have at least five, ideally six or seven players. Silk (the new character added to Horses & Stagecoach) and Mei shake up the formula a bit, in a great way, and if I am looking for chaos in a package that plays in about an hour, Colt Express is great, as both a family-weight game as well as a game that I would play with casual hobbyists. This might even work well for my Thanksgiving or other holiday meal days when family is in town.

While the module extras are fun, I recommend Marshal & Prisoners much more as an interesting game experience than Horses & Stagecoach. In both cases, I would not implement these expansions unless you are in that “superfan” category mentioned earlier—the base game is good and flexible enough for a game that hits the table a couple times each year. If you are getting the base game out monthly, that’s where I would suggest incorporating the expansions more quickly.

Colt Express holds up, more than ten years after it first hit the market. Give this a look if programming games are your jam!