Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Cities: Skylines is one of the latest titles from KOSMOS and it’s also the second board game to be adapted from a Paradox video game. Unlike its distant cousin, the dynasty-building Crusader Kings, players need not be familiar with the PC game, as the board game version steps into a well-established genre that includes popular titles like Sprawlopolis and Suburbia. This fully cooperative game can accommodate between 1 and 4 prospective urban planners, so grab your zoning permits and get to work!

You can also check out our video review of Cities: Skylines.

Happiness is a Warm Card

Like many city-building games, Cities: Skylines asks its players to balance a variety of real-world problems, like crime or overpopulation, in the pursuit of utopia. The resultant sprawl will be measured in its residents’ Happiness, a specific attribute that can be raised or lowered through various actions. Completing the city is the primary goal, but having a higher Happiness at the end is a definite plus. Players can compare their ending Happiness to a chart in the rulebook to rank their city.

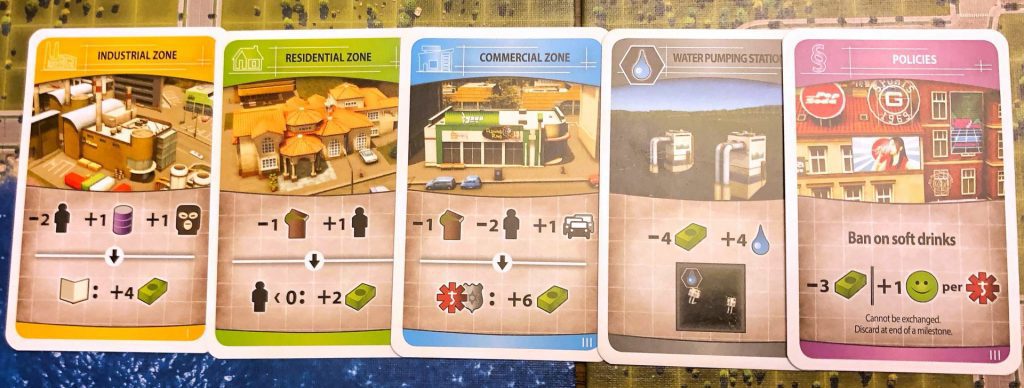

But first they’ll have to build it, a process that’s completely cooperative: no hidden information or ulterior motives here. On each turn, the active player will look at their handful of cards representing various buildings or zones, decide which one to develop, then place an appropriate polyomino onto the board. The other players can (and should!) offer input on how best to proceed, because optimizing the city’s growth will take more than one person’s brainpower.

Buildings require a specific shape and size determined by type and generally offer a set reward for their cost. Zones allow the player to choose from among the color-coded piles of unique polyominoes, with rewards often based on synergy with previously-laid pieces.

If none of the cards in hand seem appealing, the player can instead spend money to trade one card for another (either a blind draw from one of the game’s three construction decks or a pick from one of the face-up exchange piles). This offers some much-needed flexibility, though players who abuse this option will soon bankrupt their city. The game ends in failure whenever a player is unable to take an action on their turn, so keeping a reserve of money as well as one or two easy-to-play cards is vital.

The third and final option on a player’s turn, provided a sufficient number of polyominoes have been placed in each available district, is to End a Milestone. If this term seems slightly odd, it’s because it’s inherited from the video game’s leveling system. Here, it means scoring along a few parameters and then progressing to the next stage of play by paying money to reveal one of the other game boards. If all of them have been revealed, the final Milestone ends the game instead. Note that the city doesn’t have to be fully complete for the game to end in victory.

Wrong Side of the Tracks

Players can race through the game by only adding the minimum number of developments needed for each stage of the game, but even if they’re successful their ending Happiness will suffer. To get a really high score, players need to carefully maximize their outcomes every time they End a Milestone.

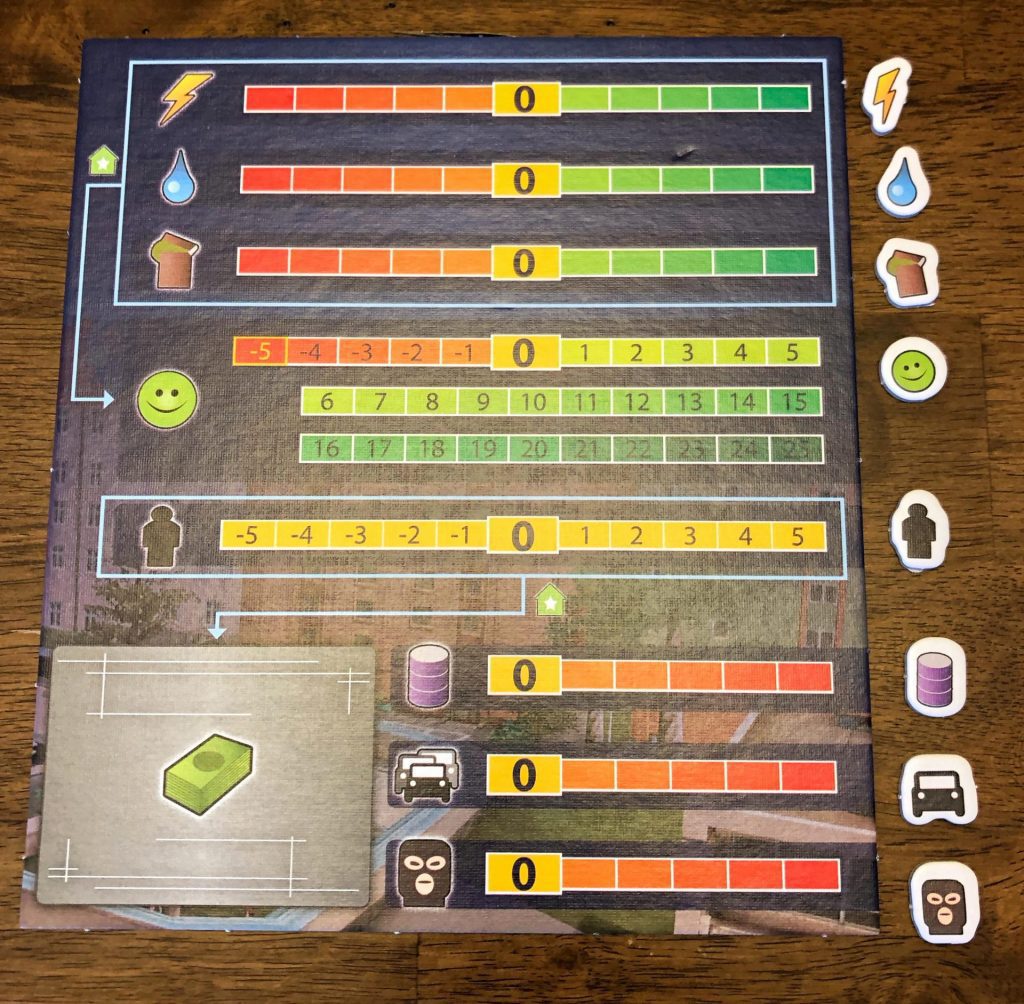

Put simply, each Milestone requires the player(s) to evaluate their performance on several tracks, adjusting their current Happiness or treasury based on how well they’ve done. The current Happiness is then added to a running total.

Utility tracks, which measure things like power consumption, penalize the players by subtracting Happiness for each point below zero. The workforce track, by contrast, requires the players to lose money for each step past zero in either direction. Underemployment is as impactful as unemployment, but neither affects Happiness at all.

And a few tracks measuring things like pollution are only evaluated at the end of the game rather than at each Milestone, meaning that your city can be a smog-smothered radioactive waste dump for all but the final turn without impacting your citizens’ Happiness.

As expected, each newly built development is going to push one or more of these tracks a little out of whack, forcing players to constantly evaluate whether the reward is worth the cost. What’s really interesting is that none of these tracks reset during the game, meaning that every single decision continues to resonate until the end. It’s easy to say yes to a little pollution early on, when it’s bringing in lots of money with hardly any consequence, but as the board fills up those decisions get significantly harder.

While the scoring system in Cities: Skylines is not particularly complex, it is devilishly effective in forcing players to manage many spinning plates. Unfortunately, it’s also not entirely intuitive. While a lot of effort has been made to make the graphic design informative and the scoring tracks thematic — residential zones add workers and industrial zones reduce them, for example —- it may still take a few turns (or games) for everything to click.

Campaign Season

Cities: Skylines anticipates the learning curve by adding a brief mini-campaign to help players get started. Each of the 4 scenarios lays out a specific map setup and adds a new layer of components/rules to build on what came before. Among the additions are role cards to give each player a special ability and unique buildings that offer powerful bonuses but have large, awkward polyominoes.

Overall, this campaign is a nice introduction to the game, though experienced gamers may want to skip ahead a bit. The news and policy cards that appear in the later missions aren’t significantly trickier to use than, say, the role cards, which will already feel familiar to many gamers.

It’s worth mentioning that all of these layers of complexity are optional: if the game feels too hard, players can use the rulebook’s guidelines to easily tweak their next playthrough by pulling a few cards out of the decks, choosing different map boards, or increasing their starting treasury.

Hard Luck Life

Make no mistake: this game can be frustratingly, even punishingly difficult at times. Finding the exact right piece or perfectly timing a Milestone feels good in the moment, yet this is a game about shrewdly managing a constant stream of crises rather than making flashy game-saving plays. Every single action causes ripple effects that later return as waves to flood the fledgling city.

With only so much room to maneuver on each track, pushing any of them too far can create massive problems; once a track is at its negative limit the players can’t build anything that would push it further. This can be a particularly painful decline, as players are forced to keep building suboptimal choices that constrict their options ever more tightly (what’s often known as a “death spiral”).

A lot of this comes down to the randomness of the draw. While some of the tension points have common solutions — there are plenty of cards that raise or lower workforce, for example — most of the tracks have only a handful of “outs” available across the three decks. If your city is completely out of power, you need one of the three power stations or one of two energy-positive policies, all of which require money to implement. That’s a mere 5 cards out of the 105 in the game.

In the meantime, every building or zone that costs power is a dead draw, clogging up your hand with unplayable options. Even the ones that don’t directly cost power are likely to do more harm than good, draining your city of the resources and space that you’ll need to recover.

This problem can be particularly egregious at lower player counts, where players don’t have access to as many cards per turn. Careful planning is absolutely necessary, and solo or duo players may want to take advantage of the options to lower the difficulty until they can consistently finish cities. Of course, those who like their co-op games on the harder side may well appreciate that Cities: Skylines isn’t a walk in the park.

If You Build It

Despite the difficulty, Cities: Skylines still succeeds in hitting all the right notes for a city-builder. The pleasant early moments of laying tiles in wide-open space give way all too soon to the low-key dread of trying to direct all that chaotic growth, yet the calming spatial puzzle of fitting polyominoes together can help ease the stress of watching the city’s coffers dwindle to nothing. And the flexibility to adjust the game to your own preferences lets it scale to the players’ skill level in a way that many titles in the genre don’t.

There are some interesting strategic layers here, too. It may seem at first like a routine exercise in efficiency, a game of trading less valuable resources for more valuable ones in an ever-changing market, yet it’s easy to become too obsessed with synergy bonuses or balancing out all the tracks, chasing an impossible equilibrium. Timing is crucial. Deciding when to push a little further and when to just accept a minor setback is a key skill, and that element of testing one’s luck remains appealing play after play.

Cities: Skylines doesn’t necessarily break new ground in a comfortingly familiar genre, but that isn’t a knock against it. This is an extremely solid design whose well-laid foundation will offer plenty of challenge as you attempt to build the city of your dreams.

Add Comment