Hello and welcome to ‘Focused on Feld’. In this series of reviews, I am working my way backwards through Stefan Feld’s entire catalogue. Over the years, I have hunted down and collected every title he has ever put out. Needless to say, I’m a fan of his work. I’m such a fan, in fact, that when I noticed there were no active Stefan Feld fan groups on Facebook, I created one of my own.

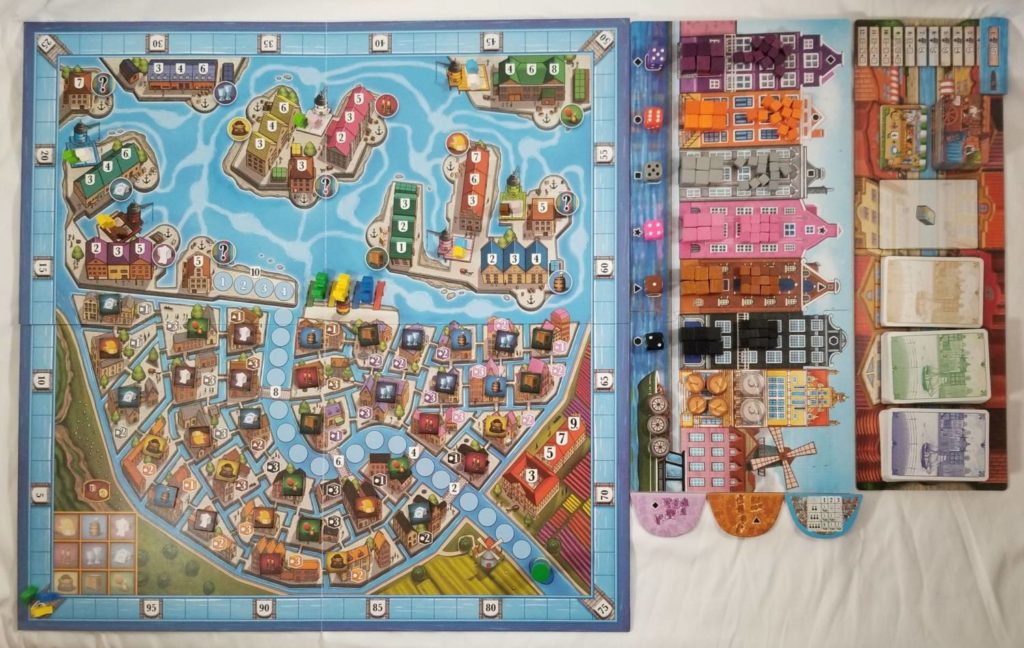

Today we’re going to talk about 2022’s Amsterdam, his 34th game.

The second game in Queen Games’s Stefan Feld City Collection (SFCC), Amsterdam is a reimplementation of Stefan Feld’s 2009 release Macao. But, as Hamburg is to Bruges, Amsterdam is more than just the same game with a shiny new veneer. The changes here run deep.

In this review, I’m going to focus on two things: What’s Changed? And What’s New? To fully understand how these changes and additions affect the gameplay, it helps to have an understanding of how Macao is played. If you’re not familiar, then I suggest you check out my review of Macao and come back.

Ready? Then here goes nothing.

The Basics

Just like Macao, Amsterdam is played over the course of twelve rounds. At the start of each round, players draft cards from a display to add to their playing areas. Then, some dice are rolled and players choose two of them for the round. The colors selected determine which color of cubes the players receive. The values of the selected dice determine how long the players will have to wait to use those cubes.

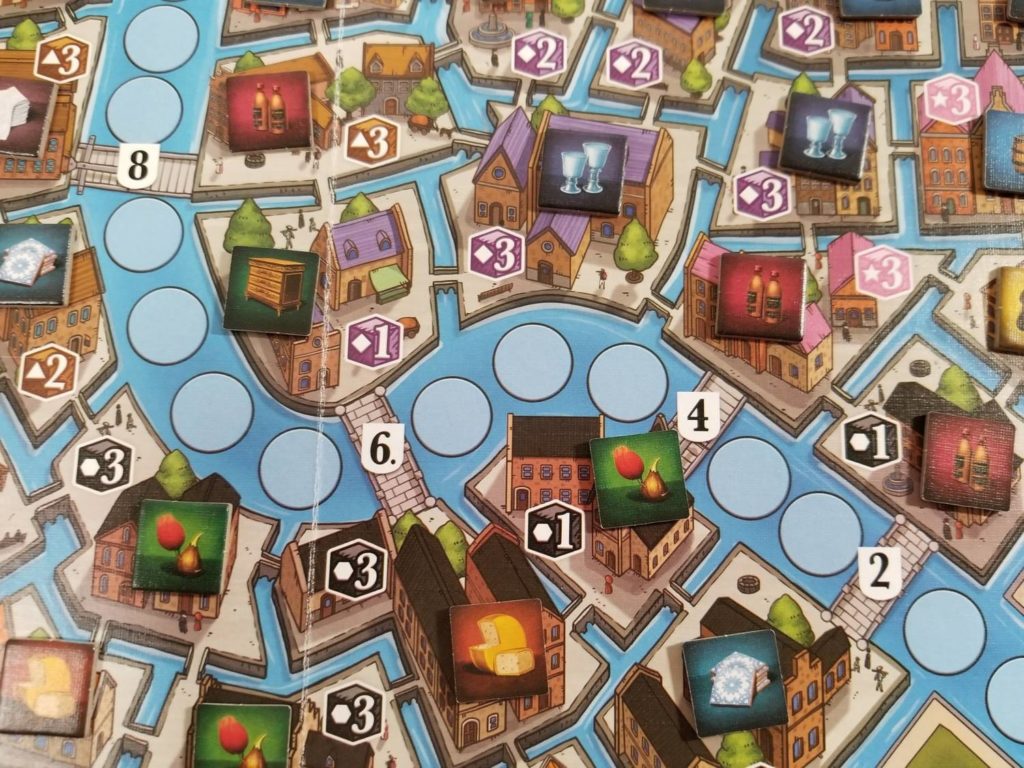

These cubes are used to perform a variety of different actions which work, in tandem, to earn the players victory points. The actions performed in Amsterdam, while nearly identical to those performed in Macao, vary in a great number of ways: what they’re called, how they function, and the overall effect they have over the end game. And, just as in Macao, players can also earn coins, which can be spent to outright purchase victory points. But even the way that works has changed significantly.

The end goal is the same: to have the most victory points once all the dust has settled. While that destination may seem familiar if you’ve ever played Macao, you’ll quickly discover that the journey has changed in some very dramatic ways.

What’s New?

There aren’t a lot of things going on in Amsterdam that don’t have some equivalent in Macao, but there are a few.

Expansions

For starters, unlike Macao, which never saw an expansion (much less a promo), Amsterdam contains four of them. The first one interacts with the shipping of Commodities and the acquisition of city quarters (called ‘blocks’ in Amsterdam) to generate more points or to reduce resource costs, respectively. The second gives each player a secret objective card that can score them extra points at the end of the game if that objective is met. The twist is that it doesn’t matter who caused the criteria to be met; the player owning the card scores the points.

The third and fourth expansions interact with two of the game’s newest features: the black market, which we’ll discuss here, and the Market tiles, which we’ll discuss in the What’s Changed? section of this review. The third expansion places a Stefan Feld standee (the black marketeer) into the black market and increases the payout for whichever good it happens to be standing on. The fourth introduces new Market tiles which replace the standard ones, giving players more interesting things to do with their money.

The Black Market

When a player acquires a city block in Amsterdam, before placing the Commodity tile received into their warehouse (I’ll get to this in the What’s Changed? section), the player has the option to sell the tile to the black market, provided the same type of tile hasn’t been sold there once already. The tile is placed into the matching space of the black market and the player receives either two gold or a cube of their choice from the supply for their troubles.

The black market strides that fine line between What’s New? And What’s Changed? because it kinda sorta exists in Macao, but not really. In Macao, there were some city quarters players could acquire which provided them with Joker tiles instead of the Commodities they’d normally receive, and these Joker tiles could be traded in at any time for two gold or a cube of their choosing. The black market’s new enough, and different enough, that I thought it belonged in this section, though.

Fast Delivery Bonuses

Each of the early rounds in Amsterdam comes with a Fast Delivery bonus. That is, for every good you deliver in a qualifying round, you’ll receive y in addition to the x you’d normally receive. The Round 1 Fast Delivery bonus rewards any player able to pull it off with seven extra victory points on top of whatever they’d normally receive. Acquiring and delivering a good that early is a tall order and not an easy goal to achieve. But it isn’t impossible like it would be in a game of Macao.

In fact, I’ve only pulled it off in a single game. Surveying the board after setup was complete, I noticed there was a city block that cost a single cube and contained a Furniture tile. The Furniture warehouse is only two steps away from the starting boat dock. I realized that if I could gain another two cubes, I could conceivably snap up the Furniture tile for one cube, deliver it using two more cubes, and net myself ten victory points on my first turn (three for delivering the first Furniture tile to the warehouse plus the seven from the Fast Delivery bonus).

Fate smiled upon me. When the dice were rolled, two 1s came up and I was able to grab the extra two cubes I needed to pull it off.

The Shack

Anyone that’s played Macao a decent number of times has encountered a situation in which they’ve had to go an entire round without any cubes to use, either through poor planning or, as is often the case with me, too much pushing of their luck. Not to mince words, turns like these suck. Not only do they result in a penalty token, but you also have to watch as everyone else gets to actually do things while you’re stuck doing nothing. Maybe, if you were lucky, you’d have enough coins saved up to purchase some prestige, but that would be about it.

Amsterdam provides a method to overcome at least a portion of this problem. You still suffer a penalty for not having any cubes to remove from your wind rose. However, you now have the ability to bank a cube on your shack at the end of each round, so you can at least ensure you’ll have a single cube at your disposal to at least do something with. Much better than doing nothing at all.

Districts

In Macao, the generic city was broken up into 30 quarters (a bit of a misnomer, if you ask me, since the word ‘quarter’ implies something that’s been divided into 4 segments). In Amsterdam, the city has been divided into blocks. And collections of blocks come together to form a District. This new concept is important for end of game scoring purposes, which I’ll talk about later.

Language Independence

Unlike Macao, which featured very text heavy cards (and often led to confusion as a result), with Amsterdam, Feld has opted to go with a more language independent approach. The net effect of this decision is that while some things are simplified, others are rendered into something much more complicated than they need to be.

On the plus side of things, players never run into ambiguous situations wherein they have to figure out which of the game’s various Commodity tiles is lacquerware. When a card in Amsterdam references a specific Commodity tile type, it simply displays an illustration of the tile in question.

On the negative side of that equation, you wind up with cards like “Oude Kerk”, “Zuiderkirk”, and “Westerkerk”, which all work in tandem to score their controllers a variable number of points based on how many of the set that person controls. The iconography for these cards isn’t immediately intuitive, which will force you to have to pore through the Addendum to figure out what they’re trying to tell you. And, thank goodness for that Addendum, because you’re going to need it for your first few games. Thankfully, all the cards are numbered and their entries are arranged numerically, as well as by color. So, it never takes long to look up whatever you’re needing.

This language independent approach is the same one Queen Games took in Hamburg, New York City, and Marrakesh (Games 1, 3, and 4 in the SFCC respectively). It’s probably a safe bet to assume every other game in the SFCC will be the same way. It’s also worth mentioning that wherever possible, Queen Games has used identical iconography across all the games.

Solo Mode

The existence of a bonafide solo mode is probably the most significant change. Macao had no such thing. This change is so significant, in fact, that I’d bet its existence is one of the main selling points that will attract consumers to the game.

What’s Changed?

If you’ve made it this far, you’ve no doubt surmised that Amsterdam’s got a lot of new features under the hood. But there are still plenty of older features leftover that have seen some tweaking, too. You’ll encounter one of these changes right off the bat during Phase 1 of the first round when new cards are revealed.

Card Reveal and Market Tiles

In Macao, the cards revealed during Phase 1 were a mixture of the two cards set aside during setup and four cards randomly drawn from a large, shared deck. The values at the bottom of these cards added up to dictate the ‘gold cost to prestige gain’ ratio for that round.

In Amsterdam, the cards have been divided into three specific types of decks: District Maps (which are usually easier to build and provide once-per-round benefits), Craftsmen (generally of the spend x to gain y variety, but not always), and Buildings (which generally provide ongoing or end-of-game scoring effects). Each round, a specific number of cards from each deck are drawn to form the pool of cards available for drafting during that round. And the ‘gold cost to prestige gain’ ratio is no longer driven by the cards. Instead, that’s the job of the Market tiles.

The Market tiles don’t just provide prestige anymore. Sometimes they provide other benefits as well, such as free movement up the Amstel River, which segues nicely into the next change: the wall in Macao has been replaced with a river—and moving up that river not only determines turn order, but it can score players a lot of points as well.

The Amstel River

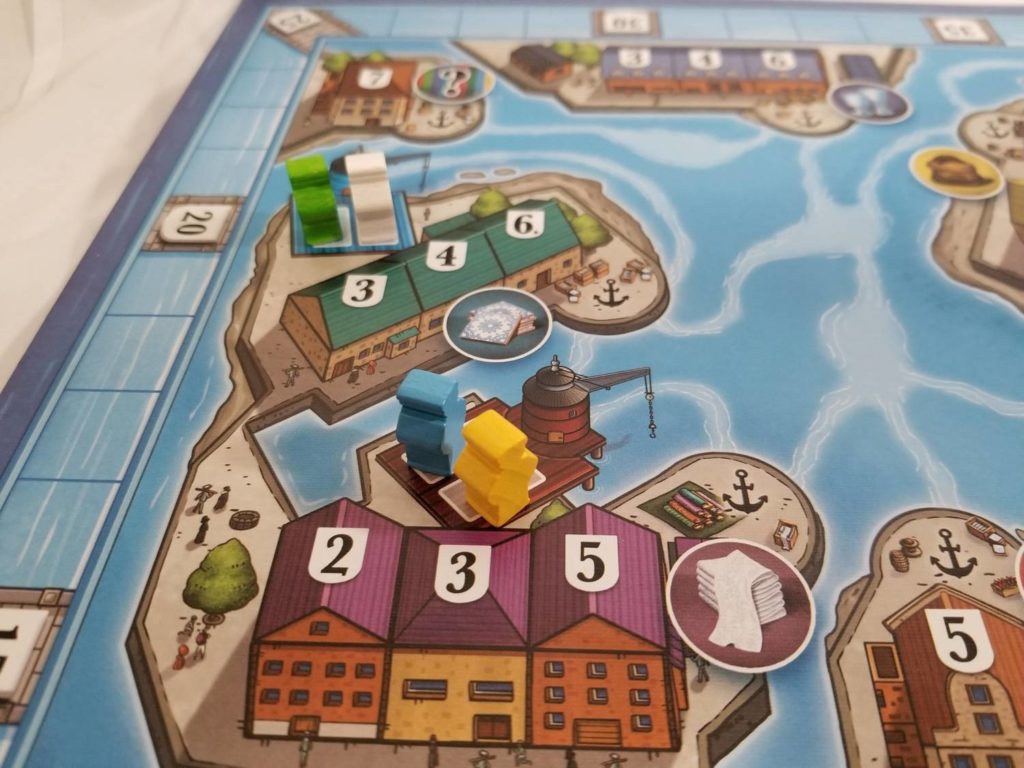

Just like the wall in Macao, the Amstel River is divided into segments. At the start of a round, the player furthest along the river will be the first player. Unlike Macao, though, the Amstel River is crossed over by a number of bridges. Moving your boat past one of these bridges will earn you points, and the further along the river you’ve moved, the more points subsequent bridge crossings are going to earn you.

The cost for this movement has changed as well. In Macao it was a simple 1:1 ratio—pay a cube, move a space—whereas it’s going to cost you one cube for your first movement, and two cubes per additional movement, during your turn in Amsterdam. So, moving three spaces would cost you a total of five cubes, for example. Without this extra cost, it’s far too easy to just rocket up the Amstel River and gain an ungodly amount of points for very little effort.

Shipping

One of the biggest, most sweeping changes is the shipping system. While it’s mechanically similar to the system that exists in Macao (spend cubes to move, deliver Commodities at the ports that want those Commodities), the shipping system has received a massive, and much needed, overhaul. So much so that it’s almost unrecognizable.

The changes begin the moment you acquire a Commodity tile from claiming a city block. Instead of going directly to your boat, that tile is sent directly to your personal warehouse on your player board. The tile can only be loaded onto your ship if your ship is berthed at one of the several docks-with-cranes dotted around the board. Those docks serve a secondary purpose as well: they’re a place for you to pick up and/or deliver dock workers.

“Dock workers?” you may be asking yourself. During setup, each dock receives a pair of differently colored dock workers who have but one desire: to be delivered to the dock matching their color. When you arrive at a dock where dock workers are waiting, you may take one of them onto your ship (receiving a coin for your troubles). Later on, if you’re able to deliver them to their preferred dock (the yellow worker wants to be delivered to the yellow dock, for example), you’ll add them to the Magazine (a large, sectioned building at the bottom of the board), where they will score you victory points. The points received for delivering workers reduce in value as more workers are delivered. So, it pays to be first to do it.

End Of Game

Earlier, I mentioned that Districts would become important during end-of-game scoring. So, allow me to elaborate. During setup, a number of moon-shaped tokens will have been selected. These tokens, each displaying one of the six different Districts, determine which Districts will have area-majority scoring performed on them at the end of the game. This is in addition to the points each player scores for their largest cluster of Control markers within the city, which has changed from two points per Control marker to three points instead.

And that brings me to my last change. Much like the point values of Control markers have changed, Penalty tokens no longer have a flat rate of minus three points apiece. Instead, their effect is cumulative, costing you 3/8/15/22 for having 1/2/3/4 of them. And each Penalty token beyond that is going to cost you a whopping 7 points!

The Setting

The game’s setting is the most obvious change. Players are no longer 17th century Portuguese seafarers. Now they’re 19th century Amsterdammers.

Thoughts

I’m going to make this short and sweet…

Amsterdam has replaced Macao for me. I doubt that I will ever open my copy of Macao ever again for as long as Amsterdam lives in my collection.

Comparatively, Amsterdam is just the better game. It’s more balanced, it looks nicer, it plays more smoothly, and it’s chock full of those ‘big game moments’—moments where you’re able to activate a ton of cards to do a ton of stuff as your little boat races around the victory point track. It seems like Macao should produce these, but just never does.

Amsterdam fixes all the things that ever bugged me about Macao (and, boy, were there a lot of them) and even adds a few new things that I never realized Macao really needed. As I played through my first game of Amsterdam, I realized THIS is why the SFCC exists. There was a cynical part of me that wanted to believe that the SFCC was just Queen Games trying to capitalize on players’ deeply held respect for a well-known game designer to fatten their wallets. This has been well and thoroughly shut down. Instead, that naysaying voice inside of me has turned into a proselytizer now, shouting the praises of the SFCC from the rooftops for those who choose to hear.

If you’re reading this, I hope you’re listening.

Add Comment