Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

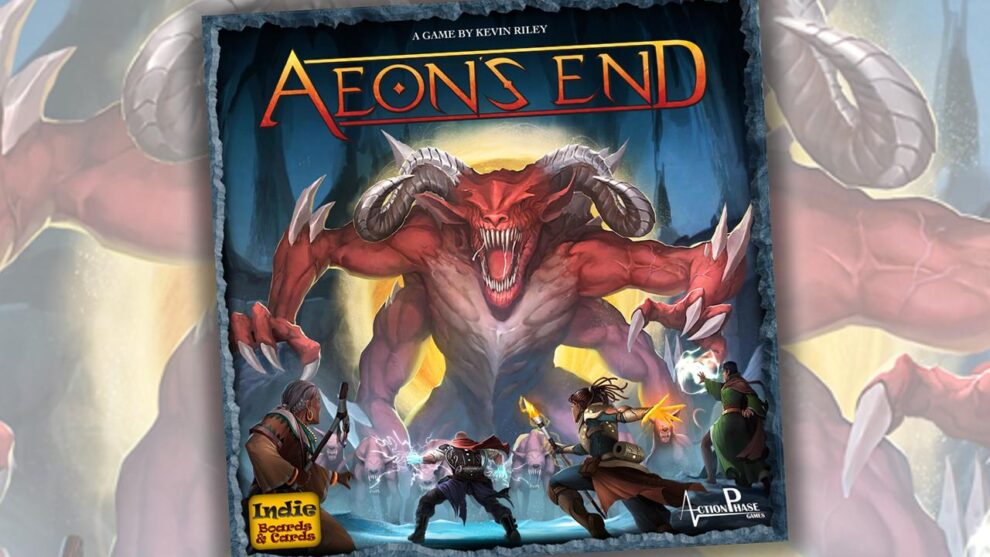

I lost my first 15 games of Aeon’s End, the revered 2016 cooperative deck-builder from design team Kevin Riley, Nick Little, and Jenny Iglesias. I am not proud of that, but I think it’s important for you to know because it immediately tells you two things: Aeon’s End is hard, and Aeon’s End is compelling. There’s an argument to be made that it also tells you that I am bad at Aeon’s End, but that’s a matter of opinion.

Aeon’s End Is Hard

At first, I didn’t see much of a difference between Aeon’s End and a host of other cooperative deck-builders. It doesn’t make significant changes to the design space, at least not at first glance. You cast spells to deal damage to baddies and spend money to upgrade your deck. It seemed to me that we’d been here before.

Like many coop games of its kind, the entirety of Aeon’s End is focused around a big ol’ baddie. As Breach Mages, you fight one of the Nameless, come to destroy the city of Gravehold. You would think that the residents of Gravehold would have known they were courting disaster when they named the city “Gravehold,” but here we are.

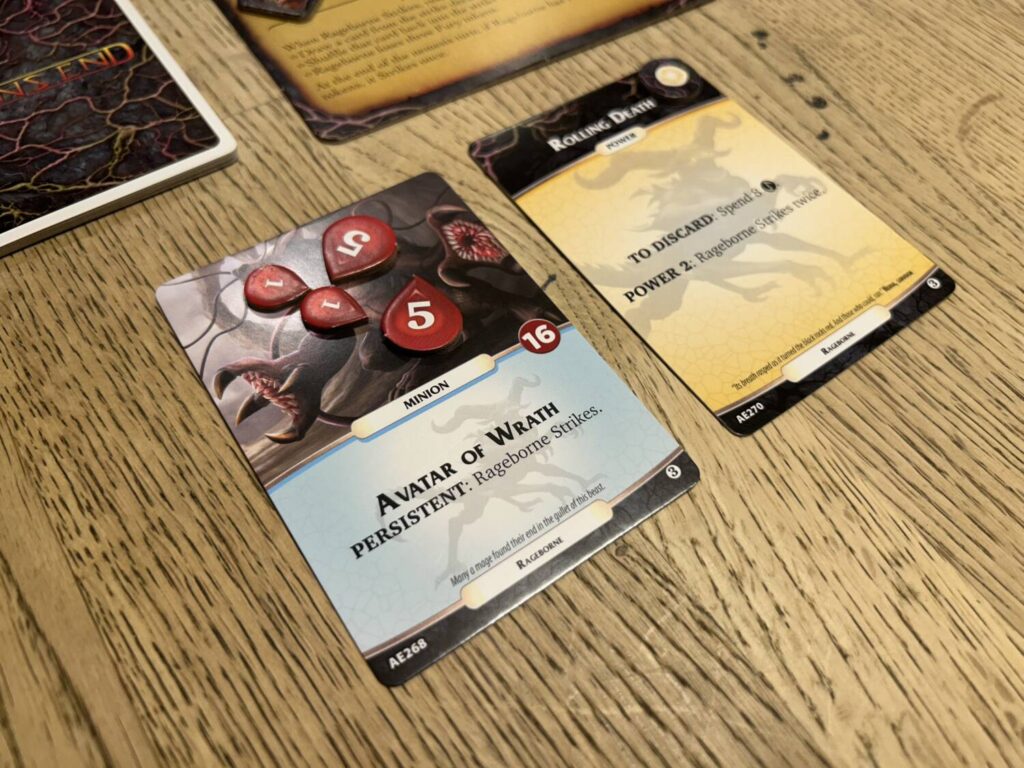

The Nameless are vicious, and varied in their tactics. The Carapace Queen—they do, in fact, have names—floods the zone with her insect offspring. Rageborne is big, dumb, and angry, gnashing its way through the city’s defenses. The Prince of Gluttons and The Crooked Mask muck around with the meta of a deck-builder, consuming cards from the market and shuffling bad cards into your deck.

No matter who you fight, the Nameless are punishing. Both the city and individual players constantly bleed life, slowly at first and then in bursts. You might shrug off 3 damage to Gravehold in an early round, but you won’t feel that way for long. The Attacks, Powers, and Minion cards that constitute the Nameless deck become progressively worse as the game continues. If you fall even a touch out of step with the tempo, the horrors compound. Their non-stop pace necessitates good play, and good play in Aeon’s End is not easy.

“Good play” in a deck-builder is often a relative proposition. One of the criticisms leveled at Dominion is that victory comes down to luck (which is not to say it’s all luck). Your final standing isn’t a matter of the deck you construct, but whether or not your cards came up in the order that you needed them to. Did that Throne Room/Bridge combo work out, or did that Throne Room keep showing up with a handful of Coppers? A deck-builder that demands skilled play rather than simply rewarding it is a bit like a slot machine that asks you to have the dexterity of a neurosurgeon.

Aeon’s End gets away with it because of the central conceit: you never shuffle. When your deck runs out, you take your discard pile and turn it over. This is deck-building without the entropy, at least on the player side of things. You’re often thinking three or four turns ahead, doing the math on where cards will end up in relation to one another. You don’t cross your fingers and hope for combos, as you so often do in other deck-building games. You set those combos in motion through meticulous planning.

That unprecedented amount of control comes at a cost. If you bloat your deck even a bit, you will pay for it. If you allow your deck to get out of order, you will pay for it. If you misjudge when to cast a spell, you will pay for it. Aeon’s End is a high-end sports car, with the responsive steering that implies. Overdo it and you may end up in a ditch.

Aeon’s End Is Compelling

I kept playing again, loss after loss after loss, because I could feel myself improving. Those first fifteen games were with the same pair of Mages, the same card market, and the same Nameless. At some point during each game, I would experience a minor revelation about card play, pacing, the best strategy for each character, or how to adjust for the Nameless. Again and again, I would realize some mistake I had just made, but it wasn’t discouraging, because I knew I had made the mistake. It wasn’t a bad draw, it was a bad choice.

It didn’t help that those early games were digital. It’s easy to miss rules when the computer handles them for you, and Aeon’s End is full of meaningful rules. That’s not to say this is a rules-heavy game, but what rules exist are there for a reason, and it is the realization of the implications of each rule that makes the system so worth diving into.

Once I finally broke through and eked out a victory, I started exploring more setups, more Mages, more Namelesses (Namelessi?). There are plenty of games that offer variety without consequence. One of the great joys of Aeon’s End has been seeing the ways in which all of the variety—if you include expansions, there are dozens of Mages, a frankly bafflingly wide selection of market cards, and heaps of Nameless—adds up to something significant. This isn’t asymmetry on par with Spirit Island, but in its much more approachable way, Aeon’s End comes close. Each Nameless requires a different strategy, just as every Mage encourages a different approach. Any grouping of Mages has to find its own unique rhythm, and that rhythm has to adjust to the particulars of both the current Nameless and the cards on offer.

While your card draw is deterministic, just about everything else is left to chance. The Nameless take their actions from a deck, a combination of cards specific to any one Nameless and a collection of generic cards. You know the core strategies, but not the incidental inconveniences, and you never quite know when any one problem is going to arise. Turn order, too, is left to chance, determined by a small deck of cards. In a two-player game, my preferred player count, the players and the Nameless take two turns each within a six-turn cycle, but you never know exactly what the order will be. This is a wonderful choice. It creates uncertainty and tension, unease, hope, the despair of sitting through a two-turn walloping and the thrill of getting four or five turns as a team during which you can unleash all manner of hell.

I Am Bad at Aeon’s End

If I could not feel the difference between Aeon’s End and any other deck-builder, that’s because I was playing Aeon’s End like any other deck-builder. I would start out growing my purchasing economy, pivot to beefing up my spells, and then try to do as much damage as possible until crossing the finish line. Then I would get my clock cleaned. I had to figure out what separated this game from Dominion, or Trains, or The Big Book of Madness. Aeon’s End is a best-in-class design, all the more exceptional for all the ways in which it seems perfectly ordinary.