The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘S’.

S – Samurai (1998)

In the late 1990’s Knizia began to look to Eastern culture, martial arts and game design for inspiration. To Knizia at the time, this meant considering indirect force, patience and the redirection of an opponent’s momentum.

The result? Samurai, the third title in Knizia’s famed tile-laying trilogy. Interestingly, Knizia himself doesn’t view the three games as a trilogy and believes they’re only linked by the community due to being three very strong tile-laying titles published in the space of two years.

Set in mediaeval Japan, players of Samurai place hexagonal tiles on the islands of Japan to surround and claim caste figures. Have the highest value of matching tiles around a figure and you claim it. Deciding the winner is a typically Knizian stroke of genius, although it can be hard to get your head around. The best definition we’ve seen is from Quentin Smith at Shut Up and Sit Down: “you get one point for having the most of each of the game’s three caste tokens, and the tie-breaker is how much you have of the other caste pieces”. It’s a deliberately tricky rule to navigate mid-game, muddying the waters as players try to remember who has been doing well with what castes. “The scoring system clearly expresses that most is not best,” says Knizia, “this ambiguity is built in and is one of the challenges”.

Whilst the gameplay appears relatively abstract, the themes and ideas Knizia was considering during the design process come through strongly. “You have to surround one piece to capture it,” says Knizia, “but if you do it all yourself in the impatient Western way, you run out of energy very quickly”. You won’t win by brute force alone, you need to be flexible and apply the right amount of pressure in just the right places. “Samurai’s portrait of fourteenth-century Japan is painted in layers”, says Dan Thurot, aka Space Biff, “it’s more about exerting the right sort of influence than storming castles, more about subtly unravelling an opponent’s plans than breaking their arms. Its thematic sensibilities seem over-abstracted until you realize that you’re furrowing your brow and brooding like a daimyo hunched over his war-map”.

The result is a game that has remained well respected for decades. “Samurai is a good time,” says Meeple Mountain’s Justin Bell in his review of Samurai, “I can see why people still whip this puppy out nearly 30 years after its initial release”. The simplicity of the design and speed of the turns mean that some have called it a “filler with depth” and yet the gameplay beneath the surface is so involved that others have commented on how ‘heavy’ it feels. “Even after two plays, I can see that Samurai has a richness that few other games have,” said W. Eric Martin, way back in 2003 in one of his very first posts after registering on BoardGameGeek (and long before he became the site’s news editor). “The possibilities start with choice of tiles, continue with figure placement, and mount with each tile or set of tiles you place. Excellent stuff.”

Like its trilogy stablemates, it’s a game that critics are fond of waxing lyrical about:

- “Samurai is like whiskey,” says Demetri Ballas at There Will Be Games, “It seems simple at first and you’ll likely get burned on your first try, but stick with it and you’ll acquire a taste for one of the best strategy games ever made… Samurai is a nigh-perfect board game. Short rules, nuanced play, difficult decisions, great aesthetics, and somehow it does all of this perfectly at all its player counts? Knizia is a wizard.”

- “Samurai is a genuinely absorbing game,” says Michael Heron at Meeple Like Us, “simple and elegant in its ruleset and full of an understated intense complexity in its game state… It lets your own fear of loss drive you to make mistakes that would be galling were it not for the fact everyone else is doing exactly the same thing. It’s a great game and I commend it to your attention.”

- “Samurai engages because every turn is a different, succinct little puzzle based on what tiles you’re holding and where your opponents are pressuring,” says Smith, “Knizia’s cleanliness and simplicity of design is a thing of beauty. The rules explanation is tiny, each turn carries weight, and the whole thing ends with a bang.”

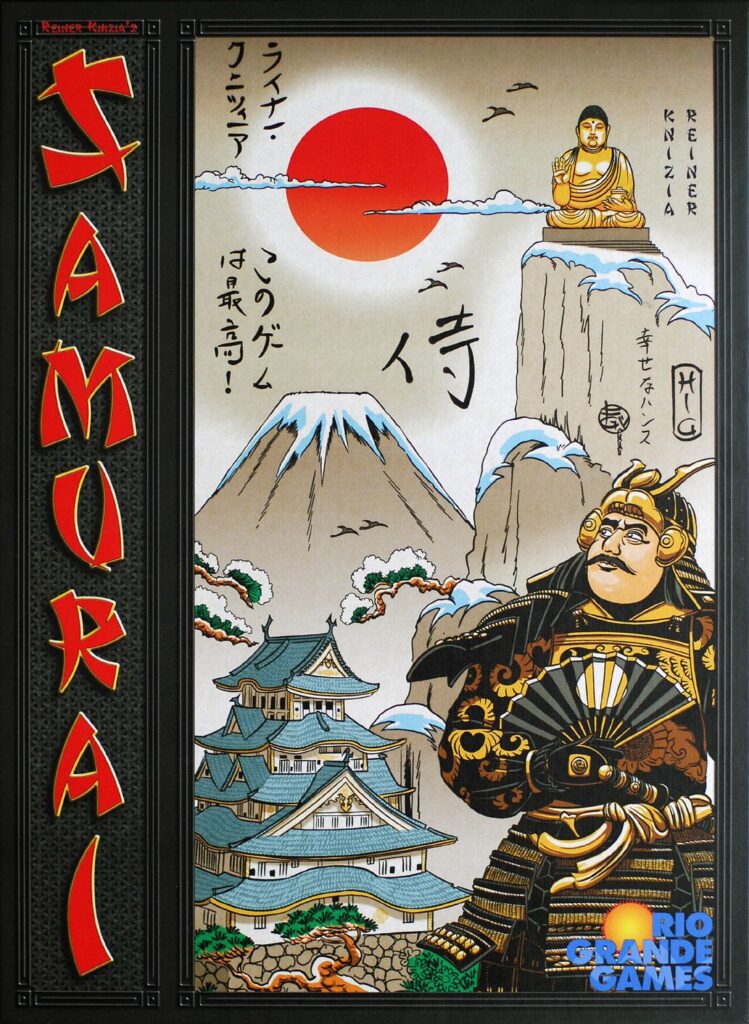

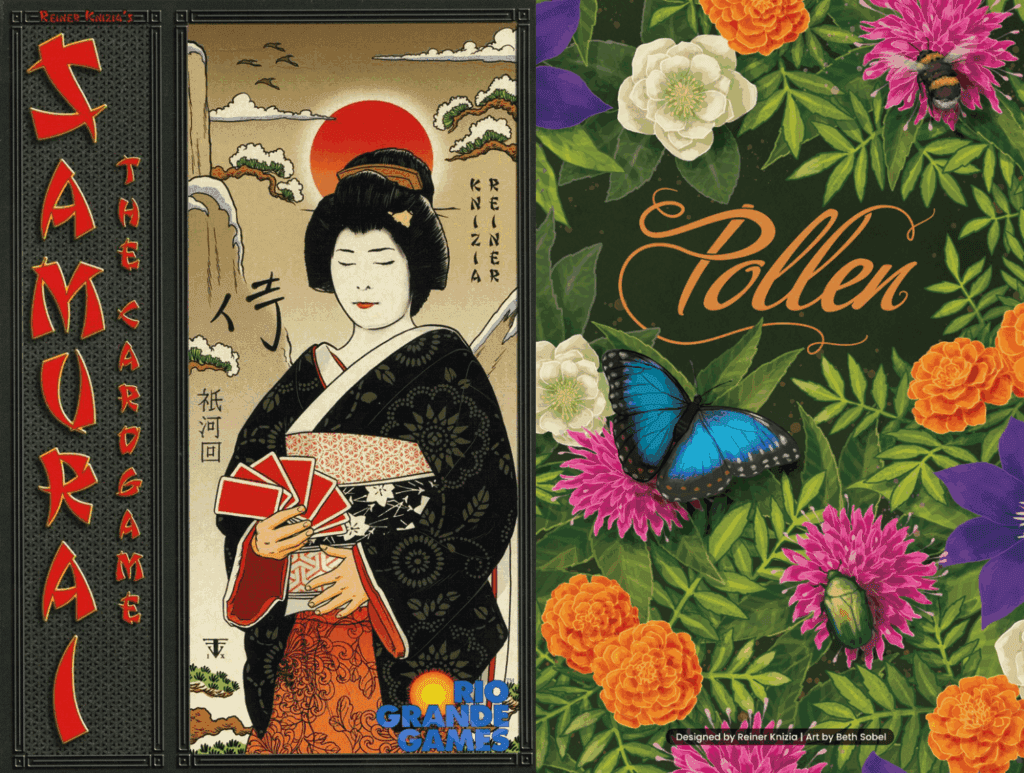

Whilst the design is what makes Samurai so compelling, it’s the original production by Hans im Glück that cemented Samurai as an exemplar product. The small black resin figures that represent the High Helmets, Buddhas and Rice Fields the players are competing for are iconic, absolute classics of tabletop aesthetic. And the front cover, illustrated by Franz Vohwinkel, is simultaneously gorgeous and a product of its time.

The Knizia of tabletop illustrations, Vohwinkel is a highly respected and prolific artist of board games, Magic: The Gathering, Dungeons & Dragons and other role playing games. At the time of writing BoardGameGeek lists around 550 games and expansions that he’s worked on, which doesn’t include his Magic or RPG work. Vohwinkel has also worked on numerous modern and classic Knizia games, many of which we’ve covered in this alphabet, including Ra, The Quest for El Dorado, Lost Cities, Taj Mahal, Blue Moon (and City), Amun-Re, Africa, Strozzi, Quo Vadis?, Money!, Circus Flohcati, Medici, Cat Blues, Tutankhamen, Orongo, and more.

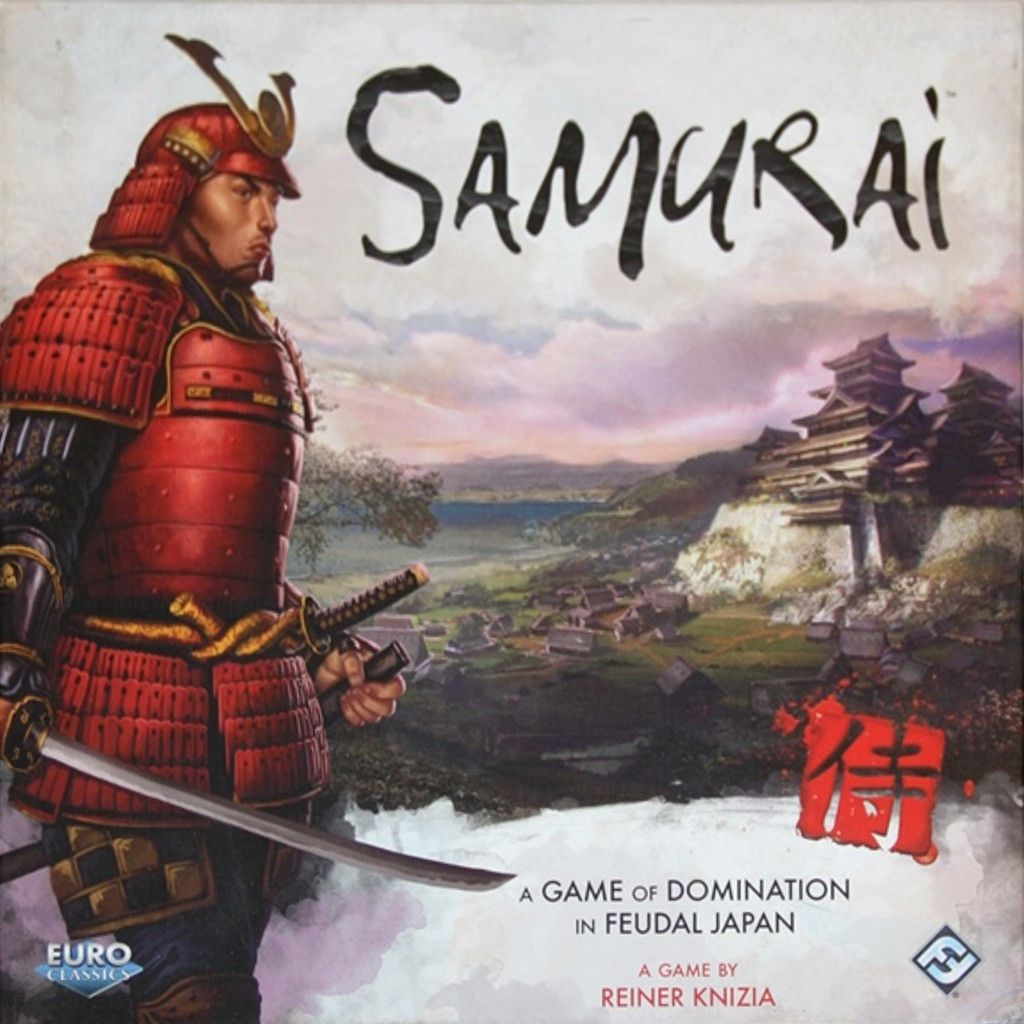

Time moves ever on, however, and 2015 saw a new edition released as part of the Z-Man Euro Classics Line, updating the production with detailed plastic miniatures and changing the High Helmets to Castles in the process. A more modern and stylish look, but perhaps a little less charming. The past couple of years have also seen new local editions and this summer an updated version of the game was successfully crowdfunded: Hanami.

Samurai is unusual amongst the most well respected Knizia titles. Despite the integration of its theme, or perhaps because of the subtlety of how the theme comes through, Samurai is frequently referred to as a purely abstract game, its theme a set dressing and nothing more. The result is that unlike many other highly ranked Knizia’s from the same period – Through the Desert, Tigris & Euphrates, Ra and even, Modern Art (Stamps excepted) – Samurai has been rethemed.

The first retheme was 2024’s 仙岛侠踪 (The Legend of Xiandao), from Chinese publisher Yaofish, which transports the game from Japan to a cluster of mystical floating islands where players compete for Artefacts, Spiritual Herbs and Ancient Scrolls hidden in caves. Hanami takes things a step further, however, changing the theme and tweaking the gameplay. This time players are competing for the best spots for Hanami (appreciating the transient beauty of flowers by viewing the blossoms), jostling elbows to view Sakura blossoms, eat Onigiri and sit under the lights of Chochin lanterns. Whilst some have groused about the new theme and appearance, Hanami is linked with Samurai culture and it returns one aspect of the game back to Knizia’s original design: the special ability.

The single-use ability to swap one caste token for another mid-game has, in every published version to date, been found on a tile that you draw at random during the game (or have in your hand from the start). Yet that wasn’t how Knizia originally designed it, and Hanami removes this tile and replaces it with a card that does the same thing but can be used at any point during the game rather than waiting for it to be drawn. Time will tell whether the change is worth it, or whether the added special abilities, tiles and second map are a success, but it goes to show that there’s still plenty of life in the engine yet.

As does 2023’s Pollen, a reimplementation of the original Samurai spin-off: Samurai: The Card Game. Transposing the area majority of the original board feels like it shouldn’t work as a card game but the same themes are present, right down to the end game scoring. And in Pollen the game is an utter delight, its insects and flowers all illustrated by esteemed tabletop artist Beth Sobel. “Pollen is classic Knizian magic,” says Meeple Mountain’s Andrew Lynch in his review of Pollen, “it is full of complex consequences that spring out of simple decisions. Each time I play, I learn something new that I want to bring forward into my next game.”

Finally, Samurai also bears the distinction of being the first Knizia game to be added to the BoardGameGeek database, and the third game to be added to the site itself, just behind #1 Die Macher (1986) and #2 Dragonmaster (1981). Knizia’s Tigris & Euphrates might be responsible for the existence of BoardGameGeek, a database that at the time of writing lists over 120,000 board games, but the seminal Samurai got there first!

Sampling Supplementary Surface-Sports

Knizia has a slew of ‘S’ games, some significant specimens we’ve singled out and salute below:

Sakura – Whilst 2018’s Sakura is technically about artists wanting to paint their Emperor, in reality it’s a wonderfully silly exploration of social awkwardness and personal space. By simultaneously selecting cards, players move both the Emperor and their painters forwards and backwards along the garden path. You want to be the closest to the Emperor when he stops to admire cherry blossoms but if you bump into him (or he backtracks into you) then you’ll be disgraced! Ever walked into someone who stopped unexpectedly in front of you? Sakura is that embarrassing moment played for laughs.

Schotten Totten – One of Knizia’s greatest two-player games (in a stacked catalogue of excellent two-player games!), we explored Schotten Totten way back in the Letter B, along with its younger sibling Battle Line. Simple cardplay, agonising decisions and comedy chickens, Schotten Totten and its sequel Schotten Totten 2 have the lot! Its a flagship Knizia design.

The Siege of Runedar – A rare Knizian foray into the cooperative tower defence genre, 2021’s The Siege of Runedar uses the bottom half of its box to create a 3D fortress that the players are defending from attacking orcs. The setting, gameplay and production help to create a machine for stories. “Its one of the more beautifully thematic marriages of mechanic and story that I’ve ever seen,” said Meeple Mountain’s Andrew Lynch in his review of The Siege of Runedar, even if it is a game he wanted to love more than he actually did.

Silos – The newest game on our list, 2025’s Silos is an update of Knizia’s very beige Municipium, released originally in 2008. No danger of beige in Silos, the brightly coloured alien, human and cow meeple pop from the nighttime town board. Players are aliens, competing to abduct and brainwash humans and cows and gain power over the town. With a quick playtime, clean rules and a lot of silly humour, Silos is worth probing.

Silver Screen – Knizia has hundreds of published games. Even if you discount rethemes, reimplementations and expansions the number is closer to a thousand than zero. Which feels even more astonishing when you discover that there are also a raft of unpublished designs, many of which are surprisingly good. Silver Screen was developed by publisher Cambridge Games Factory, whose collapse thanks to the infamous Glory to Rome Black Box Edition also cancelled Silver Screen’s development. A decade later, the game’s developer, Rob Seater, shared the unpublished rulebook and card files on BoardGameGeek. Take the time to print your own version and you’ll discover a card-based version of Nightmare Productions. According to Knizia-phile (and publisher) Nick Murray it’s “the same experience as Nightmare Productions but with a faster playtime, and with more flexibility in the decisions and paths to victory. I’m surprised to say it, but Silver Screen is my preferred game between the two.”

Stephenson’s Rocket – Knizia doesn’t have a huge number of train games, but then again he doesn’t need to when his offering is this good. Released in 1999, Stephenson’s Rocket charts the early days of railways in 1800’s England, and involves laying track, gaining stocks and merging competing rail companies by joining their tracks. You want to control stations, where the trains are going and own shares in profitable companies. “These three aspects exist in beautiful tension,” says Thoughtful Gamer Marc Davis, “Stephenson’s Rocket is the best game I’ve played in quite a while.”

Strozzi – The third game in Knizia’s Florentine auction trilogy, 2008’s Strozzi follows Medici and Medici vs. Strozzi. Where those other games looked at loading ships with goods to sell, Strozzi considers where those ships end up and how quickly they get there. Players bid to claim loaded ships and then decide where to send them, unloading them in ports to gain prestige. The result is a bidding game that still packs a punch but is easier to learn and quicker to play than its gameplay ancestors Medici and Ra.

Sunrise Lane – Developed from 2012’s Rondo, Sunrise Lane, released in 2023 by Horrible Guild, improves upon many of the original’s issues. You’re still claiming spaces on the board to score points, but with the updated version there’s now end game area scoring to consider as well, meaning that Sunrise Lane provides short- and long-term scoring tension throughout the game. “It’s punchy, it scales well for player count, and it’s easy to teach,” says Lynch in his review of Sunrise Lane, “it’s a solid choice for a family of mixed ages”.

–

So ‘S’ stops. Are you satisfied with our settlement or have we scandalised you with our sampling? Are we solid-gold or stupid simpletons? What ‘S’ would you have selected? Have your say in the comments below and set your sights on the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!