The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘M’.

M – Modern Art (1992)

Knizia’s first published game was Complica in 1985, and his first ‘boxed’ game was Digging, released in 1990.

But his first hit was Modern Art. Released in 1992, it’s rarely been out of print since.

Nominated for the 1993 Spiel des Jahres, it also received multiple national game of the year nominations, winning in Finland, Brazil and Germany (the other big German board game award, the Deutscher Spielepreis). Whilst we’re not convinced that it really should have lost the Spiel des Jahres to a variant of Liar’s Dice that had been released 6 years prior, the jury celebrated the “unusual combination of different auction types [making it] a challenging and varied game experience”. Dry praise if ever there was some.

Not a dry game though.

This is Knizia at his most interactive. Five types of auction repeating over 4 rounds, with players bidding on works of art that increase in value the more of them that are bought. This is the whole game. Some cards, some money, a lot of auctions and the richest player at the end wins.

Knizia “has always understood that games are great because of the people at the table,” says Meeple Mountain’s Andrew Lynch, “he provides a framework for interaction, rather than an object that’s meant to take up all your bandwidth”.

Whilst the quote is from Lynch’s review of Zoo Vadis, it’s just as relevant for Modern Art, demonstrating that Knizia’s abiding interest in interaction was already riding high in his early career (Modern Art and Zoo Vadis’ precursor Quo Vadis were released in the same year).

This philosophy is perhaps the most important key to Knizia’s long lasting success as a designer. “In a good game, even the losers win,” he says in the preface to the English edition of his 1990 book New Tactical Games with Dice and Cards, “It is the process of playing which is important, and the chance to interact and compete with other people. The appeal of the game is the time we spend together.”

In addition to being Knizia’s first hit, Modern Art is one of the first auction games he published (kickstarting his acclaimed ‘auction trilogy’, which, depending on who you ask, contains between three and five games). The only earlier auction game we’re aware of is Card Hunt which was published in New Tactical Games with Dice and Cards. Later reworked into 2007’s Escalation!, the simplicity of Card Hunt gives no indication that Knizia would later become renowned for auction games, only hinting at the concept of an auction if you squint.

The early Modern Art prototypes were similarly restrained. It was always an auction game, but Dave Chalker at Critical Hits records that it originally consisted of only 25 cards, with a full game lasting around 10 minutes. Knizia felt it was too small, too short, so he extended it with multiple rounds. He then realised that it needed to be more interesting, not just longer so introduced end-of-round scoring. The rest is gaming history.

The result is Knizia’s most bombastic entry in the auction arena, the auctions controlling both the simple set collection and the value of the sets being collected. “Simply hearing what your friends bid is fascinating,” says Quentin Smith of Shut Up and Sit Down, “and awful and clever and cruel and unfair and hilarious and – yes – fun”.

The five different auction mechanisms add an opaque cloud over what artworks are worth and who might pay how much for them. “This creates a delicious sense of desperation,” says Andrew McAlpine of There Will Be Games, “as players must constantly be aware of these shifting tides”.

The changing fortunes of the artists and motives of your opponents make it a game that’s difficult to navigate. “It’s not the simplest auction game in the world,” says Michael Heron on Meeple Like Us, “you don’t do anything in Modern Art without making everything more complicated for everyone. Every bid you make is laden with implication”. Smith agrees, but stresses that this aspect is what makes the game soar. “It’s confusing as all hell, and that’s precisely why this game works,” he says, “the puzzle is just too complicated for any kind of a solution… it’s a masterpiece.”

The word ‘masterpiece’ is rarely bandied around so readily (unless we’re talking about the expansion for Knizia’s Mille Fiori) and is symptomatic of the language lavished upon Modern Art:

“One of the most beautifully subtle games on the market,” says Dan Thurot of Space Biff.

“That puzzle is rich and redolent, scented with promise and opportunity.” says Heron. [Editor’s note: the word ‘redolent’ doesn’t feature in tabletop writing enough, bravo Michael!]

“One of the most fascinating game theory simulations I’ve ever encountered,” says Marc Davis of The Thoughtful Gamer.

Knizia “masterfully manufactures the feeling of being a player in an industry defined by the fickle and arbitrary tastes of the fabulously wealthy,” says McAlpine.

But it’s not just a clever set of mechanics. As the above quotes suggest, Modern Art also nails its theme. “This game oozes the theme,” says Meeple Mountain’s Joseph Buszek in his review of Modern Art, “taking you and your fellow players into the beautiful and backstabbing world of art dealing and collecting.”

We’ve seen Knizia dip his toes into satire before with High Society, but Modern Art might just represent the satirical summit of his entire output. As players bid on works of art, they drive up the prices of other works by the artists responsible and reveal how economics fuels the art world. “Modern Art mocks its namesake,” says Eric Twice, “paintings aren’t bought because they are great or beautiful. Rather, they are desired because speculators have made them popular.” Were Knizia designing it today it might be about NFTs.

In his essay ‘Reiner Knizia, Master of Theme’, Michael Barnes describes Modern Art as a “perfect example of how rich a game’s theme – as opposed to its setting – can be… The actions, as well as the themes they illustrate, serve to parody speculation and the fine art marketplace”. The success and longevity of Modern Art comes down to its “seamless pairing of subject matter and mechanics,” says McAlpine, “it both recreates the art world and presents a nervy critique of it – no small feat for a game that essentially consists of a deck of cards and a pile of tokens”.

Of course, no game is flawless. Despite his use of the word ‘redolent’, Heron wishes that the speculation aspect of the game was stronger and feels that the game loses its energy in the final round. “It’s also psychologically incapacitating,” he says, “I find it hard to convince myself that there’s enough skill as opposed to sheer luck in the outcome”. Davis, meanwhile, feels that its satirical bite isn’t as original or sharp as it seems, feeling that big money art helps to subsidise art that wouldn’t exist otherwise. “The fact that value is subjective, and may be informed by economic calculation,” he points out, “isn’t much of a showstopper”.

And the game is entirely dependent on the engagement of its players. Sometimes it falls flat. Some people bounce off Modern Art in the same way that many are nonplussed by modern art itself, Knizia included. In an interview with Caffeine & Cardboard, Knizia states that despite the game’s success, his taste runs to classical art. Having moved to the United Kingdom the year after Modern Art was released, we wonder what he thought of Young British Artists such as Damien Hirst and Tracey Emin whose work came to dominate the art scene in the 1990’s.

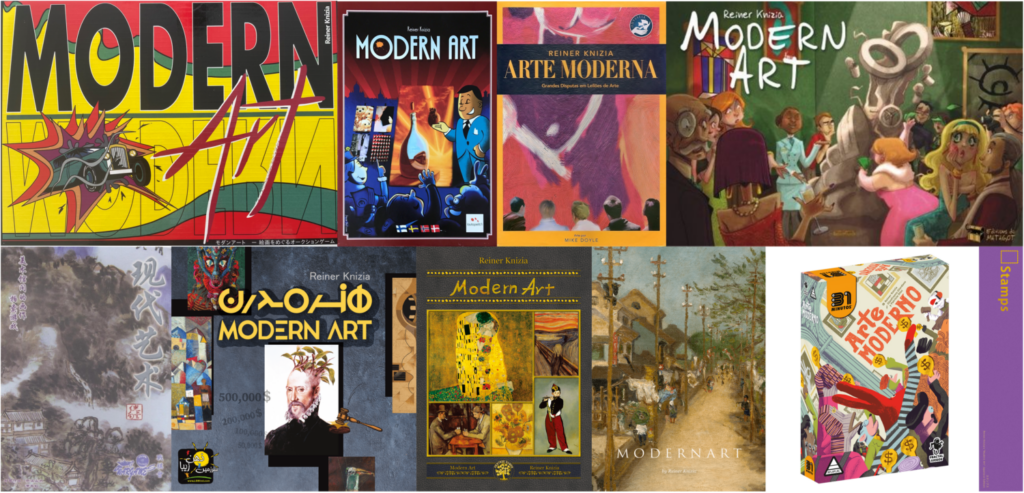

As with many Knizia hits, the success of Modern Art resulted in further investment in the ‘brand’. The lineage, however, is remarkably restrained, at least in terms of spin-offs. In creating Modern Art, Knizia stumbled upon his version of Monopoly – a game that could be easily localised for regional markets. The Nordic edition has works from Finnish artists. For its in-game artists, the Chilean edition features puppets from the Chilean television show ’31 Minutes’. In Japan, Oink Games released a 2011 edition called Stamps, a tribute to some of the gorgeous postal stamps printed in the country (and not, as you might think, about Japan’s popular eki stamps).

Some editions use famous works of art by artists of global renown, early movers in the modern art movement such as Cezanne and Picasso. Some editions use existing art by lesser known artists. Still others use art specifically commissioned for the game. The earliest editions fall into the latter category, with fictitious artists such as ‘Karl Gitter’, ‘Krypto’ and ‘Yoko’ parodying the likes of Rothko, Pollock and Lichtenstein. We’d like to thank the real artists portraying the fake artists parodying the real artists, but it’s simply credited as the Zeilbeck & Natzeck Design Company, the game making more of an artistic statement than the art contained within it.

Debates over which of the 35 editions of Modern Art is best continue to this day. Stamps is even a gaming holy grail for collectors. Some point out that using famous artists, however, undermines the game’s satire. “If the paintings on sale are terrible, we are hyping out something without value,” Twice says, “we fool others for profit and laugh all the way to the bank. But, if the paintings are well-known, that’s no longer the case”. Fittingly, arguments over editions add another layer of commentary about the appreciation, value and business of art.

Of course, as with many of his games, Knizia has explored the design space around the game. Sixteen years after the original gave him his first hit, Modern Art: The Card Game was released. Whilst the game forgoes the auctions completely, focussing instead on the art speculation, the first edition kept the original fictitious artists, having “all found fame and fortune in the art world”. It’s a lovely bit of continuity, sadly lost in later editions. Publisher Eagle-Gryphon Games also addressed the ‘real vs. fake which artists’ debate, simultaneously releasing Masters Gallery, the exact same rules as The Card Game but with works by artists such as Monet, Renoir and Van Gough.

A newcomer to the Modern Art family is Classic Art. It married into the lineage in 2023, having first been released as Members Only in 1996 and then Glenn’s Gallery in 2010. Classic Art deals loosely in some of the same themes, this time with players speculating on the popularity of five areas of classical art.

Modern Art may have been a huge success but Knizia knows he can’t rely on his previous hits. In an interview with Billy Langsworthy on Mojo Nation he talks about how his student playtesters haven’t played his older games. He can’t rest on his laurels and whilst auction games aren’t as popular as they once were, he’s been studying different auction types and there are plenty of avenues he’d still like to explore.

Until then, Modern Art remains one of the high points in his career, the epitome of Knizia’s ability to convey a lot more to the players than what’s in the rulebook alone. Ben Maddox over at The Cult of the Old sums it up perfectly: “This is the power of Art. Art isn’t pure but it is vital and Modern Art is the definition of vitality.”

Mountains of Marvelously Moreish Merrymakers!

‘M’ is a major Knizia letter and there are many (a)muse-bouches and main courses to munch upon (Knizia has even made a version of the world’s most successful board game: Monopoly: Stock Exchange). Here are some of the most memorable:

Marshmallow Test – Advertised as ‘The delayed gratification trick-taking game’, 2020’s Marshmallow Test, is actually a reimplementation of Voodoo Prince, released three years earlier. This year it’s also being reimplemented once again in the form of Piñatas, released in Wave 2 of publisher Allplay’s ‘Surprise! Nine Secret(ish) Board Games’ Kickstarter campaign. Whilst there are minor differences between these three trick-taking games, Marshmallow Test is notable for its squishy marshmallow scoring tokens and is, according to Meeple Mountain’s Trick Taker’s Guide to the Galaxy, a “rambunctious and snappy game of chicken”. Watch our review of Marshmallow Test here.

Medici – The second game in Knizia’s auction trilogy, 1995’s Medici feels like the unloved middle child, the most underappreciated major hit that he’s had. It’s obviously a successful game, spawning two separate spin-offs and its own family title (Knizia’s Florentine auction trilogy). But despite the plaudits, these days it’s rarely mentioned in the same breath as its stablemates Modern Art and Ra. Which is a shame because its merchants and auctions are well worth visiting if you can get hold of the gorgeous third or fourth editions (alas, the first and second editions are notoriously unattractive once you get past the box covers).

Merchants of Amsterdam – Notable for its inclusion of a spring-driven auction clock for the Dutch auctions throughout the game. Dutch auctions are where the auction price starts high and incrementally gets lower until a bid is received – it’s the auction equivalent of chicken, with players wanting a bargain whilst hoping their opponents don’t snap it up first. Dutch auction-style markets are common in board games (in Suburbia, for instance, tiles are revealed at the highest price and move down the market decreasing in price as they go). Real-time Dutch auctions, however, are far rarer and 2000’s Merchants of Amsterdam is the earliest example we know of. This year publisher Allplay is releasing a reimplemented version set in space: Merchants of Andromeda.

Mille Fiori – A collection of mini-games fused into a beautiful whole, Mille Fiori has players drafting cards to place translucent coloured diamonds around the board and scoring points in a variety of ways. In his review of Mille Fiori, Meeple Mountain’s Andrew Lynch describes it as “a perfect game for groups looking to find a compromise between the constellatory calculations of the [Stefan] Feldian and the approachability and interpersonal dramatics of the Knizian”. If you’re looking for the Knizian take on the point salad genre, this is it.

MLEM: Space Agency – Push-your-luck dice rolling with cats in space. Players attempt to propel their cat-astronauts across the galaxy, scoring points for landing them on yarn or goldfish planets and hoping that the rocket doesn’t crash. For some people that’s enough of a sell, and many critics out there are fans of this slickly produced game. Not our Andrew Lynch though: in his review of MLEM: Space Agency he explained that despite the unique cat abilities, the game is far from purr-fect.

Money! – A clever currency trading game, Money! was first released in 1999 and this year has been given a new coat of paint by publishers Allplay (again!). Its simple gameplay rewards repeat plays and Money! is another of Knizia’s numerous Spiel des Jahres nominations. Whilst the rules have stayed largely the same over the years, the exclamation mark in the title disappeared in 2008 and has only just reappeared. “Twenty-six years after its debut,” says BoardGameGeek’s W. Eric Martin, “I expect to see new editions of Money! for many decades to come”.

Monkey Madness – It’s easy, as someone in the hobby, to forget that Knizia designs games for the whole family. Monkey Madness is a colourfully cute game released in 2001 for children aged 3 years and up. Knizia himself has said that it sold well despite getting no recognition from tabletop critics. Ever aware of good business practice, he notes that the mass market is bigger but quieter than the designer market.

My City – Knizia’s first foray into the legacy arena, 2020’s My City turned out to be a huge hit. Legacy games are often complex or involved and Knizia’s aim was to create a more approachable game that would appeal to gamers and casual players alike. Nominated for the Spiel des Jahres, its own legacy is a roll-and-write game and a more complex sequel. We don’t have the space to go into detail here but you can find out more about the ‘My’ trilogy by reading the Meeple Mountain reviews of My City, My City: Roll & Build and My Island.

–

We’ve reached the end of the menu of ‘M’! Or at least, we’ve run out of space, despite there still being several notable Knizia ‘M’ games we’ve not discussed! In particular look out for Manekinecollection’s cat accumulating, Marabunta’s battling ant colonies, and Municipium’s area majority, which is being released in a remastered edition by Bitewing Games as SILOS, involving invading aliens and plenty of cows.

How did we do with the games we included? Do you celebrate our manifesto as a meritorious marvel? Or, will you malign it as a manifestation of malodorous malediction? What ‘M’ game is your closest match? Let us know in the comments below and check out the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!