The guys in my Wednesday gaming group started a push to play more of the old, dust-covered games at the bottom and backs of our respective game closet shelves. The premise was simple: let’s try to remember why we keep all these old games when all we ever play now are the newest, shiniest things in shrink.

Right on the spot, the Dusty Euro Series was born, and I’ve enlisted multiple game groups to help me lead the charge on covering older games.

In order to share some of these experiences, I’ll be writing a piece from time to time about a game that is at least 10 years old that we haven’t already reviewed here at Meeple Mountain. In that way, these articles are not reviews. These pieces will not include a detailed rules explanation or a broad introduction to each game. All you get is what you need: my brief thoughts on what I think about each game right now, based on one or two fresh plays.

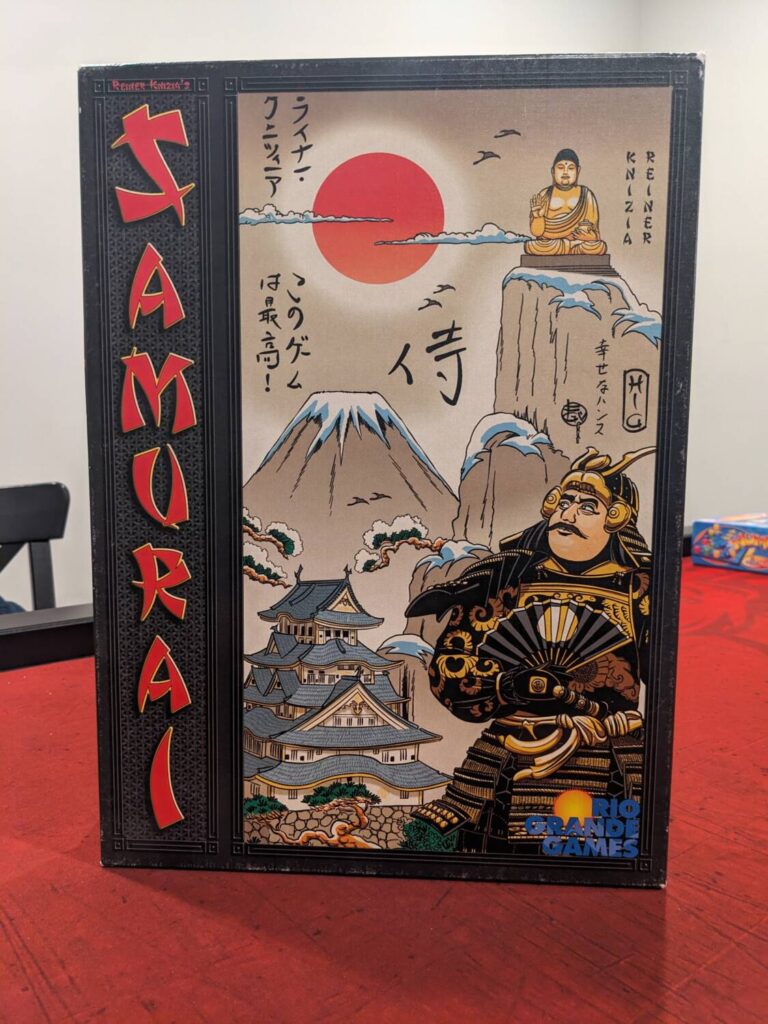

Samurai: What Is It?

Samurai is an area majority tile placement game for 2-4 players. As it happened, Samurai also aligned nicely with a few things—we hadn’t written a full-blown article on the game, it was designed by Reiner Knizia, and it is a member of the top 500 most popular games on BoardGameGeek.

“Wait, you have never played Samurai?” My buddy John was both shocked and in awe of the fact that I had somehow never played it. “I will definitely bring that to the next Dusty Euro game night, and you will see why it is a classic.”

He was right, in part because I will play anything with simple rules, tense decisions, and a short playtime. During our 25-minute three-player game, Samurai had it all thanks to such an interesting, emotional roller coaster.

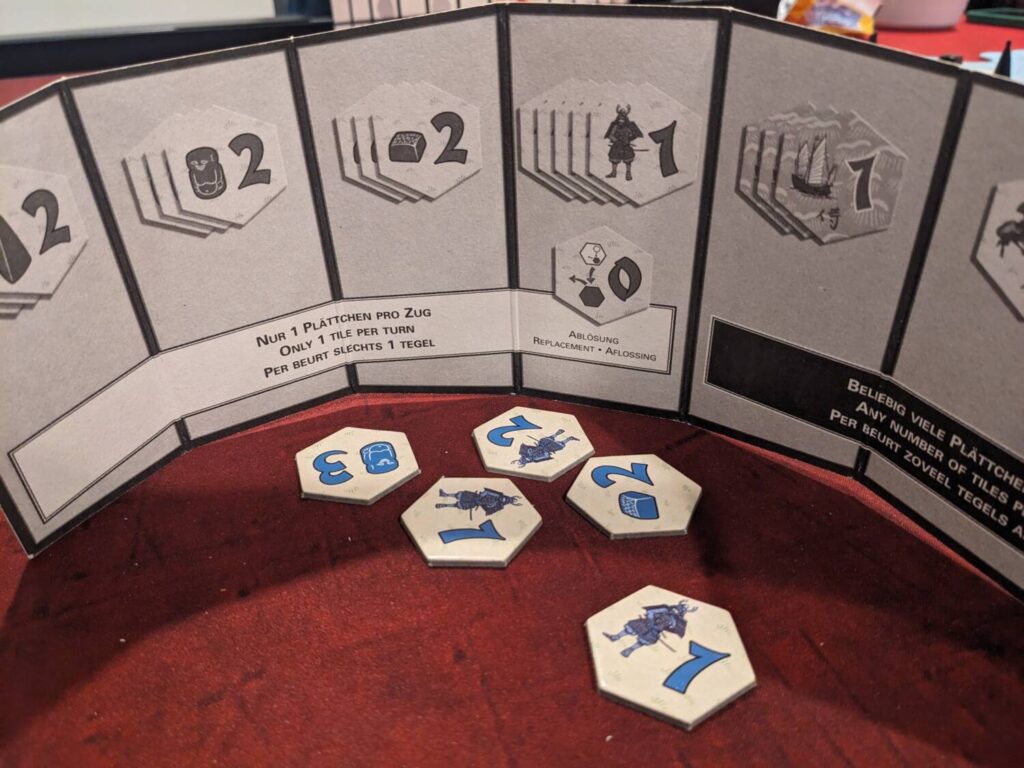

The rules are simple. The board is a series of interlocking hex tiles that feature islands in and around a territory that represents medieval Japan. Beautiful miniatures—especially for a game published in 1998—are used to represent samurai (helmets), peasants (rice fields), and priests (Buddha statues), and are placed in various spaces on the islands. Then, players shuffle their sets of matching placement tiles in front of a screen before drawing five of them in hand, secret only to their owner, behind their screen. The youngest player goes first.

On a turn, players can place one or more tiles on the map, a series of hex-shaped spaces featuring the miniatures that were placed during setup. When a miniature is completely surrounded by tiles on land spaces, a miniature is captured by the person who had the largest majority in strength (between tiles that match the unit type as well as samurai strength, which is used to score everything). In a sneaky twist, some of the tiles represent boats that can be placed adjacent to a miniature that resides next to water, giving players something else to plan for. A small set of each player’s tiles has a symbol that allows them to place an additional tile on their turn.

When all units from one of the three miniature types are completely removed from play, the game immediately ends. Players now reveal the units they have captured (scoring during play is kept secret), and if any single player has captured the most of two of the three unit types, they win. Ties are then broken by players who have tied for capturing the most of a single unit type. Amongst eligible players, the one who has captured the most other unit types wins!

Simplicity Personified

Samurai is one of those rare games—or, maybe not so rare, if we are talking about Knizia tile-laying games—that truly lives up to the phrase “a moment to learn, a lifetime to master.”

Samurai is very easy to teach, and as an abstract that can get rolling in just a few minutes, Samurai fits the bill. But there is so much more to how turns shake out, thanks to the random-but-limited nature of how new tiles are drawn and trying to plan for what an opponent might currently have behind their screen. I loved that five of each player’s 20 tiles could allow for a back-to-back tile-laying turn. That means that you can’t guarantee that the person playing before you might drop just a single tile before it is your turn.

Plus, what if that player has all five of their back-to-back tiles currently behind their screen? That means they could play as many as five tiles, in a row, all over the map, throwing your plans into disarray.

There are also a couple of special tiles that break the game’s rules, like one that is a zero-value strength tile, usable to replace an existing tile. That grants its owner an opportunity to move one tile from one area to the next. (This also means I will be watching in future plays for when players have exhausted that tile, so that I can’t get sniped like I did in my single play!)

The boat/sea tiles are interesting, because they may or may not be used as a feint while someone plans to really try to capture a different tile later. Or maybe they will be used to set up a capture of a unit on the same turn as a back-to-back play.

Samurai’s main challenge is its player count. For reasons that are likely my own, Samurai feels like a game that should accommodate five, even six, players. That would lead to even more chaos than currently present, but then again, for a game this short and featuring scores this low, I would be totally fine with a larger map and more figures available for capture.

But at three players? Samurai was a good time and I can see why people still whip this puppy out nearly 30 years after its initial release. Count me in!!

Samurai plays differently at 2,3,4 players. It’s an amazingly good game if the players are of similar skill