This past Christmas, my wife bought me a pre-constructed Magic: the Gathering Commander deck, which is set in the Doctor Who universe. Doctor Who appears within Magic: the Gathering as a part of an initiative called ‘Universes Beyond’. This series, based on various IPs, features other settings such as Lord of the Rings, Avatar: the Last Airbender, and Fallout (to name a few).

It was an unexpected, but welcome, gift to say the least. I haven’t played Magic: the Gathering in years (I’ve never played the Commander format), but I do love me some Doctor Who. So, I wasted no time tearing into it to check out the cards, and I have to say: I’m in love. From the artwork to the card mechanics to the flair text, the theme oozes from every card. It’s exactly what you’d want from a Doctor Who themed Magic: the Gathering set.

As I sat there reading the cards and trying to understand how the deck worked, I felt something long dormant began reawakening in me: the desire to play. And, as I sat there reading over the cards, it became apparent to me that I’ve been out of the game for far too long. Unfamiliar keywords, command zones, color identities… my eyes crossed trying to parse everything. Magic is an ever-evolving game and it has changed A LOT since the last time I played it.

This got me thinking about playing again, and that got me thinking about sharing my experience with you. So, in this series of articles, I am going to teach you how to play Magic (in case you’re unfamiliar with it), I’m going to let you join me on my journey as I try to build a Commander deck using the random cards I’ve collected over the years, and we’re going to learn what the word ‘Commander’ actually means. I can’t promise you that the deck that I wind up with is going to be the best deck that’s ever been built, but I can guarantee you we’re going to have fun.

So, without further adieu, let’s dive in.

Chapter One: Getting Started

The Part Where I Tell You My Story

I can clearly remember the day that I played Magic: the Gathering (just Magic from here on out) for the first time. Or, more specifically, I clearly recall the night.

The scene opens in Raleigh, Tennessee on a warm summer night in 1997. I was visiting my friend Erin and sitting across from her and her boyfriend, Tim. Erin’s mom had recently plied us all with chili. As we sat there at the table letting the warmth of the chili settle in, Tim suggested we play a few rounds of Magic. It was a game I’d heard of, but had no experience with other than watching a few friends play it incessantly back in high school just a few years earlier. Erin was only slightly more experienced than I, having been introduced to the game by Tim a month or two prior. Tim was, by far, the most seasoned Magic player at the table and, as it would turn out later, he wasn’t seasoned very well.

“Sure, I’ll play.” I said. “But I’d have to use someone else’s deck.”

Tim nodded and dug around in his box of Magic cards for a few moments before producing a deck for me to use. Then, he proceeded to give me a tutorial.

The Part Where I Tell You What Tim Taught Me

The basic game of Magic pits two players against one another in a head-to-head duel (although there are variants that can accommodate more). Each player begins the game with 20 life and wields a deck of at least 60 cards, composed of spell cards and lands. Lands come in two types: basic and non-basic. The basic land cards are forests, swamps, plains, islands, and mountains. Each of these can be used to produce a specific type of ‘mana’: forests = green (G), swamps = black (B), plains = white (W), islands = blue (U), and mountains = red (R). ‘Mana’ is the money that you use to cast spells. Pay attention to this casting cost shorthand (G,B,W,U, and R) because I will be using it A LOT in this and the following chapters in this series.

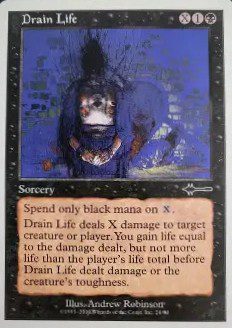

Each non-land card has a casting cost, which is printed in the top right corner of the card. This cost is shown as a series of icons which correspond to the mana types and sometimes a circle with a number in it which indicates that ‘colorless’ mana can be used (that is, it doesn’t matter which color of mana you use to pay for it). As you’ll see in a moment, in the casting cost shorthand, colorless mana is always represented by a number. Some spells may include an X in their casting cost, and the text on the card will define what that variable means.

To better understand that, let’s consider this example: Drain Life. Drain Life is a black card with a casting cost of X1B. That is, one colorless mana, one black mana, and X which the card defines as “Spend only black mana on X. Drain Life deals X damage to any target. You gain life equal to the damage dealt, but not more life than the player’s life total before the damage was dealt, the planeswalker’s loyalty before the damage was dealt, or the creature’s toughness.” That last italicized bit is just a fancy way of saying, you can only drain something down to 0. You can’t make it go into the negatives. So, if the player sitting across from you only has five health, you can’t drain more than five life from them. To do so, you would ‘tap’ one swamp to pay for the B in the casting cost, an additional land to pay for the 1 in the casting cost, and five other lands to pay for the X. Then, the target would lose five life, and that amount of life would be added to your own life total.

To better understand that, let’s consider this example: Drain Life. Drain Life is a black card with a casting cost of X1B. That is, one colorless mana, one black mana, and X which the card defines as “Spend only black mana on X. Drain Life deals X damage to any target. You gain life equal to the damage dealt, but not more life than the player’s life total before the damage was dealt, the planeswalker’s loyalty before the damage was dealt, or the creature’s toughness.” That last italicized bit is just a fancy way of saying, you can only drain something down to 0. You can’t make it go into the negatives. So, if the player sitting across from you only has five health, you can’t drain more than five life from them. To do so, you would ‘tap’ one swamp to pay for the B in the casting cost, an additional land to pay for the 1 in the casting cost, and five other lands to pay for the X. Then, the target would lose five life, and that amount of life would be added to your own life total.

We’ll talk about the differences between players, creatures, and planeswalkers at some other time (maybe in the next article). Hopefully, after reading that, you’ve got a better understanding of how to cast a spell. Just as important as knowing how to cast a spell is knowing when. Looking back at Drain Life, you might notice the word ‘Sorcery’ right above the card text. This is the spell’s ‘type’. In general, there are only a few types of cards: lands, planeswalkers, creatures, sorceries, and instants. Unless the text on a card specifies otherwise, lands, planeswalkers, creatures, and sorceries can only be played on your turn. Instants can be played at any time. Even that is a broad generalization, as turns are divided into several phases, and the cards you can play on your turn can only be played during specific phases. Here are the phases as they were when I was originally taught the game:

- Untap – Any cards that were tapped between the active player’s last turn and now are untapped. This is the second time that I have mentioned the keyword ‘tap’, so it seems prudent to define the word. ‘Tapping’ (that is, turning a card on its side) is how you show that a card has been used for something. In board game nomenclature, this is often referred to as ‘exhausting’ something. ‘Untapping’ is just the act of returning the cards to their upright position.

- Upkeep – Many cards have things occurring ‘during your upkeep’. Whatever those effects are would occur during this phase.

- Draw – Draw a card from your deck and add it to your hand.

- Main Phase – If you have a land in your hand, you may put it into play (‘onto the battlefield’). Then, you may use the lands you have in play to produce mana to cast spells.

- Combat – Use your creatures to attack your opponent. We’ll get more granular with this in a moment.

- Second Main Phase – Cast more spells, if you wish. If you haven’t put a land in play yet, and have one in hand, you may play it now. It is important to note that, unless some card effect breaks the rule, you may only put one land into play per turn. Sorceries may only be played during these Main phases.

- Discard – If you have more than seven cards in hand, discard down to seven.

The last thing to talk about is Combat.

Each creature has a power value and a toughness value, shown on the bottom right corner of the card in an X / Y format. The X value represents the creature’s power: the amount of damage it will do to another creature or player. The Y value represents the creature’s toughness; how much damage the creature can sustain before it dies. If this is ever reduced to 0 and remains at 0 by the end of the Combat phase, then the creature dies and is added to its owner’s discard pile (called the ‘graveyard’ in the game).

During the Combat phase, the active player will declare which creatures they are attacking with. Then, the defending player has the opportunity to declare which creatures they are blocking with. The attacking and blocking creatures deal damage to one another simultaneously, possibly causing some of them to die and be added to their owners’ graveyards. Any unblocked attackers deal their damage to the defending player directly. The amount of damage done is subtracted from that player’s health and, if their health is ever reduced to 0 or less, they lose the game.

This is one way to win. The game can also be lost if you are ever asked to draw a card from your deck (a.k.a. your ‘library’) and there are no cards to draw. And, it is worth noting that all of the above can be altered or changed by casting the right spells at the right time. For instance, if my opponent ever reduces my health to 0, but I use an instant card to recover some health, I’m still in the game. Or, if it comes to my draw step and my library is empty, if I use the ability of a card to shuffle my graveyard into my library, then I can do so and prevent myself from losing the game in this manner.

It is worth noting here that, unless specified otherwise, creatures cannot attack the turn they entered play. Nor can they use any of their abilities that would require them to tap to do so. I game terminology, this is referred to as “summoning sickness”. It’s also worth noting that, unless specified otherwise, when creatures attack, they become tapped as a result which makes them ineligible to be used as blockers should your opponent retaliate on their turn. This is something you’ll need to keep in mind for sure.

The Part Where I Tell You What Tim REALLY Taught Me

Then, we proceeded to play. What followed was a lesson in misery. I thought I had a good grasp on the rules, but Tim always found some loophole that allowed him to win. And, every time he won, he would cackle and belittle me. Why is he being this way? It didn’t make any sense, especially considering that the deck he was playing against was one that he’d built himself. The way he treated me that night was not without repercussions. Tim had really ticked me off. I didn’t like being bullied, and I left there determined to build my own deck that would wipe the floor with him.

Instead of chasing me away, Tim had awakened a monster, one with a singular purpose: defeat Tim. Defeat him at all costs—and, just like that, I was on my way. I’d heard Magic’s siren song, and I was powerless to resist. But, I was determined that I would never be like Tim. I would never gloat when I won, and I would never sour when things didn’t go my way. Tim taught me to play with respect and humility by his total lack of both.

The Part Where I Tell You What I Wish Tim Had Taught Me

Earlier in 1997, I’d met a girl on America Online, and we’d started dating. I had a trip planned to go up to Maine later that year to meet her in person and spend some time with her and her family. A few weeks after that night at Erin’s, I found myself talking to this girl about how I was really starting to get into playing Magic. As it turned out, her brother, Jaric, also played, so I was doubly excited for my upcoming trip. I couldn’t wait to show him the amazing deck I’d built.

For weeks, I’d been buying booster packs and shoving cards that I thought were really neat into a deck, tossing in a couple of lands for every two or three cards that got added. By the time I met up with her brother, I was excited to show it off. That first game, he defeated me soundly. After setting his cards aside, he steepled his fingers thoughtfully.

“David,” he said, “Are you open to critique?”

Uh, oh. This didn’t sound good. I steeled myself for what was coming next.

“Sure,” I said, feeling less confident than I sounded. “Fire away.”

“I’m not going to mince words here,” he said. “Your deck sucks, and I’ll tell you why.”

“It’s too big. There’s no theme to it. There’s no strategy. And your ratios are way off,” he stated matter of factly, ticking off each bullet point on his fingers. “But, if you’ll let me help you, with a little bit of tweaking and restructuring, I think we can turn this into a decent deck.”

Nobody likes their hard work to get dumped upon. My initial reaction was to get rankled, but I remembered my goal: become better than Tim. And, part of that was conducting myself like a respectful human being. So, I said yes.

That day, I learned about synergy. He plucked two cards out of my deck and held them up side-by-side: a Sengir Vampire and a Nettling Imp. “Let’s start with these,” he said.

“Sengir Vampire gets stronger whenever it ‘eats’ a smaller creature. We can use Nettling Imp’s ability to force those smaller creatures to attack during your opponent’s turn. Then, we block that creature with the Sengir Vampire. But, here’s the kicker. If you block with multiple Sengir Vampires, they all do damage to that creature, and they all gain the benefits. If we reduce the size of your deck from its current size of 150+ cards down to 60 and add four of each of these to it, that’s 8 out of 60 cards already, and we vastly increase our chances of drawing them when we need them.”

With just that single suggestion, I could already see how right he was, and I could begin seeing the possibilities. We spent another couple of hours poring over the cards that I owned, fleshing out my Vampire deck. He recommended a couple of singles that I could purchase that would set off the deck and helped me understand the strategy behind everything we’d done. As we were wrapping up, he spoke again.

“David, as we were playing earlier, I noticed you were trying to do a lot of weird things, and I had to keep stopping and telling you those things couldn’t be done. Why were you doing those things?”

“Well, the guy that taught me the game, Tim, was doing them. So, I thought they were a part of the game.”

“This Tim guy sounds like an idiot.” I couldn’t disagree. Jaric dug around in his box where he kept his cards for a moment, retrieved something from it, and then handed me what he’d retrieved.

“Here,” he said. “You can have this.”

He’d just handed me the keys to the kingdom. He had given me a rulebook. Tim, as it turned out, was a cheater, a charlatan, and a liar. Armed with knowledge and a solid deck, I returned to Memphis a few days later.

Tim never won a game of Magic against me or Erin ever again. Deprived of clueless schlubs to play against, he just couldn’t compete. And, just as I’d promised myself, I was better than him. I didn’t lord the fact that he couldn’t win against me over him. I kindly corrected him whenever he tried to cheat, and when it was over, I gave him the rulebook that Jaric had given me.

Jaric taught me not only how to play, but also how to dole out criticism, how to accept it, and how to share my experience with others in a way that helps more than it hurts.

The Part Where I Tell You What Magic Taught Me About Myself

For the longest time, there were only two ways to play Magic competitively: constructed play and drafts.

Booster drafts haven’t changed much over the years. In a booster draft, you build a deck on the fly and then compete against the other players at the table using what you’ve just built. You purchase a few booster packs, open them, select a card to keep for your deck, and then pass the remainder to the person sitting on one side of you, receiving the leftovers from the person sitting on the other side of you. Rinse and repeat until all the cards are drafted. The shop owner provides you with some basic lands, you shuffle your deck, and then start playing. Booster drafts are a great way to get your eyeballs on a lot of different cards for a reasonable price. When you receive another person’s cast-offs, you have a choice to make: focus on improving your deck, or hang onto specific cards that aren’t going to benefit you in the tournament but might be useful outside of it later. Booster drafts are an exciting way to play Magic, but constructed play, building your own deck beforehand and bringing it with you, is where most people who play Magic focus their efforts.

The way the game was set up for constructed play was that there was a core set of cards to choose from, and there was a themed ‘block’ that ran alongside it. Each ‘block’ shared some storyline and was composed of three sets of cards. As one new set was rotated in, whichever set had been rotated in three sets ago was rotated out. If you wanted to compete in a tournament, then your 60-card (minimum) deck could only be composed of cards from the core set plus whichever three sets were currently rotated in, with no more than four copies of any single, non-basic land card in your deck.

The constant rotation of cards in and out of the game meant a significant buy-in if you wanted to compete. And, if you really wanted to compete, just relying on whatever you happened to pull from booster packs wasn’t going to cut the mustard. You were going to be forced to buy singles, and these were going to cost you. And, that’s how it was for decades.

What I discovered about myself is that I had an addictive personality, and I had very little self-control when I was in the sway of that addiction. I spent a LOT of money on Magic cards. Money I didn’t really have. Even though I knew that I was being stupid, I couldn’t help myself. I just kept right on spending.

In 2001, I moved to Nashville with my best friend and we took up residence in his aunt’s attic where we spent most of our free time playing Magic or watching Battlebots. While I should have been hitting the pavement finding myself a job, I wasted my time hanging out in the local card shops where I spent what little money I had sitting in my savings. I knew I was being an idiot, but I just couldn’t stop. In the autumn of that year, there came a knock at the door. It was the repo man who had come to take my car away.

There was nothing I could do to prevent it. I lost my car and, with it, I lost my place to live. His family didn’t mind him still living there (he was family) but they couldn’t support me, too. Without any recourse, I had to move back to Memphis and move in with my father. I felt like a failure, and it was years before I’d get to see my best friend again. It was a low point in my life, and it served as a wake-up call. The only way to move forward was to stop moving backwards.

So, I packed my cards away and vowed to never let Magic rule my life ever again. Magic was an absurdly expensive hobby, especially if I wanted to stay relevant. Over the next few decades, I’d buy a booster pack here or there just to see what was new. There was even a brief resurgence when my now wife and I were still dating, but that had fizzled out fairly quickly because it was just too expensive for us to keep it going.

It seemed that would be the way it would always be. Then, around 15 years ago, something amazing happened in the world of Magic: a new format emerged that breathed new life into the game, turning my moldering boxes of old cards into a treasure trove of new material and possibilities.

Commander had entered the arena.