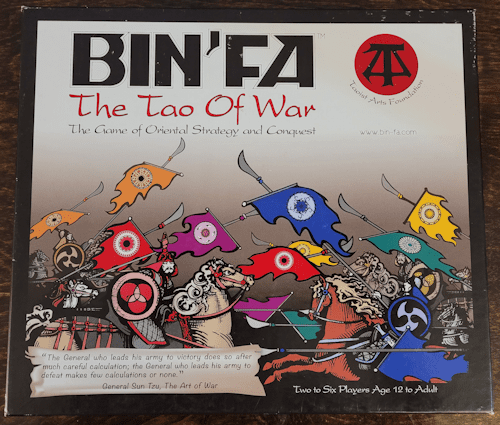

Bin’Fa (a.k.a., Hexagony) is a unique creation. It has the basic trappings of an old-school wargame: armies moving across a battlefield attacking one another in a quest for supremacy. It has rules for things like supplies and terrain; over the years it has added rules for generals, weather, and even teleportation (vortexes). But calling it a wargame does not feel right. Bin’Fa is different. It is a contradiction of sorts: as you look deep into its inner workings, it reveals itself to be simultaneously far more, yet significantly less, than the sort of thing one associates with the term wargame.

If it is not a wargame, the question becomes: what is Bin’Fa, exactly?

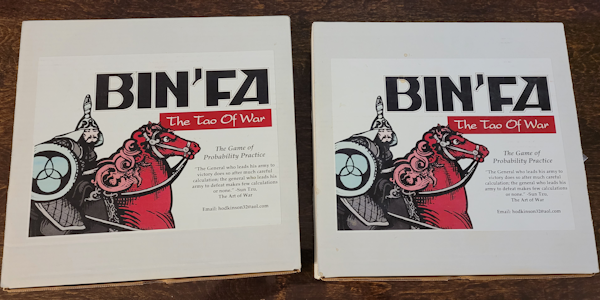

That question is not easy to answer. Bin’Fa has gone through many iterations over the years. I am fortunate enough to own every published version of the game as well as two copies of a version that was never published (more on that later). Each release has been just a bit different from the last; there have been rules updates between releases of the game that range from exceedingly minor to majorly transformative. Bin’Fa has evolved over time. Still, the core concepts have remained surprisingly stable over the years.

Understanding Bin’Fa – getting to know it and truly appreciating its beauty – means getting to know its history. To that end, let us dive into that history. Let us examine the inner workings and see what makes this quirky little game tick. Maybe, just maybe, when we are through, we will have some idea as to how to answer that question.

The Long and Winding Road

A good overview of the publishing timeline of the game can be found on the official Bin’Fa website’s history page. On this page is the heart-warming story of Ken Hodkinson, a gaming enthusiast, and his journey as he passionately develops and publishes various versions of Bin’Fa over a 50+ year timespan. He has managed to publish several versions by himself, and for a while partnered with another company to get his vision out into the world. In the end, he took back control of his creation, continued to work on the rules for decades, and ended with what he considered the definitive edition of the game. It is a beautiful story well worth a look or ten.

That said, this article’s focus is not the publishing timeline. Granted, some coverage of that topic is unavoidable; the focus of this work is the evolutionary timeline. What I want to explore is how the game started with a solid foundation and grew over the years into something quite special.

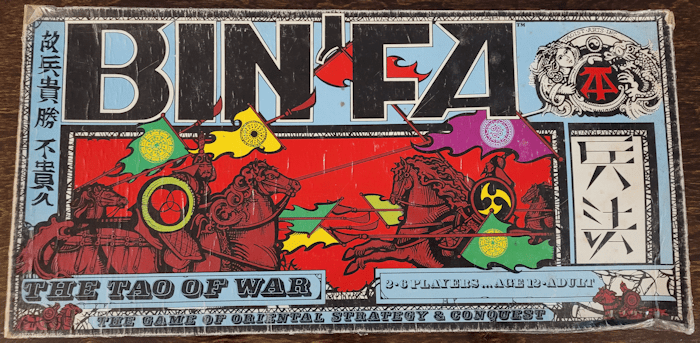

1977 – Bin’Fa (limited edition, Taoist Arts, Inc.)

The game was first conceived in 1971. It was not until 1977 that Bin’Fa would make its first foray into the public eye. This first self-published edition had only 500 copies. Mr. Hodkinson created Taoist Arts, Inc. as the imprint. This was the inception, the original state, of the game! In order to understand how the game evolved, one must start with an understanding of where it began. Click the button below to learn how the game is played. This will be important later on.

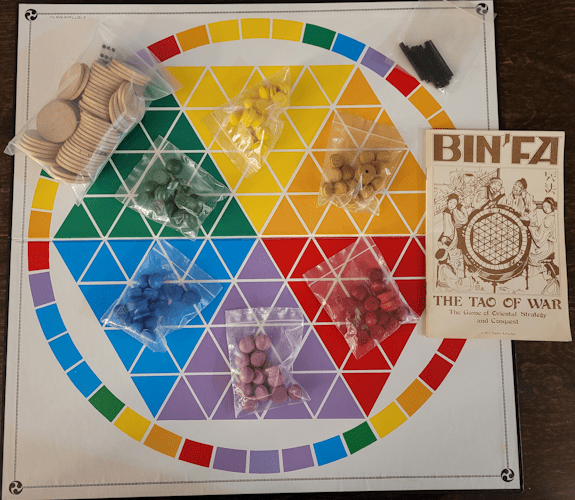

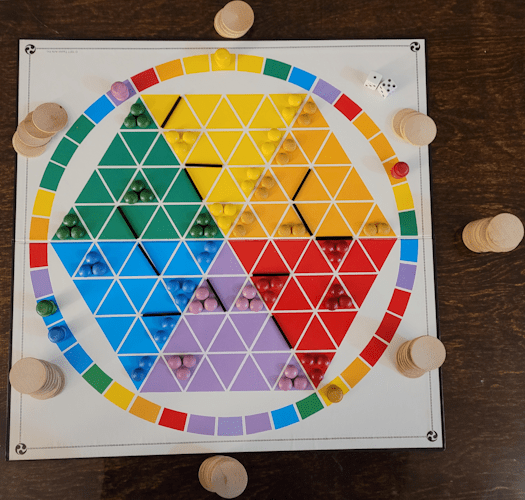

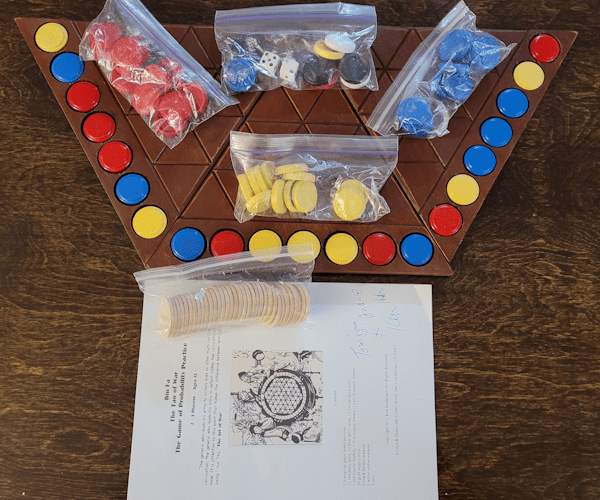

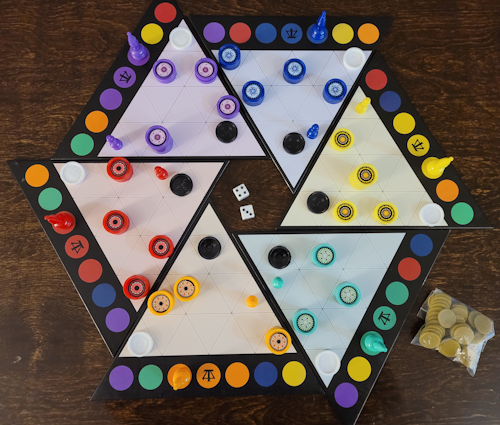

Bin’Fa is a strategy game for 2-6 players played on a hexagonal board (the battle sector). The battle sector is divided into six large wedges (regions), each a different color. Each region is further divided into 16 triangles (spaces). Encircling the board is the separate track (the supply sector) made up of roughly rectangular spaces of the same six colors of the battle sector.

The spaces along the supply sector change from space to space; however, at the outer edge of each region, there are three spaces in the supply sector that all have the same color as that region (the region’s home supply area; more on these in a moment).

The remaining components of the game are:

- 12 terrain markers (small black plastic sticks)

- 12 armies and 1 supply marker in each of the six colors

- 60 supply tokens (wooden disks)

- 2 six-sided dice

- 1 game board

- 1 rulebook

When starting the game, place the board in the middle of the table. Gather the supply tokens (supplies) into a pile near the board (the bank).

Divide the terrain markers between the players. In a random order, players position each terrain marker on the battle sector along the border between two spaces. Terrain markers are impassable; no terrain marker may be placed in such a way that one portion of the battle sector is completely cut off from another. Players continue placing terrain markers until they have all been placed.

Each player draws a random supply marker. The color of this piece determines the player’s color (faction) – the color of the armies the player will use and the region in which they begin play (their home region). Once the factions have been determined, players can arrange themselves so they are seated closest to their home region.

Players then place all 12 of their armies. Armies may be placed onto any space within the player’s home region. No more than three armies may occupy a given space (the stacking limit). Additionally, players place their supply marker onto any space within the supply sector. No more than one supply token may occupy a given space.

Finally, each player rolls the dice and takes a number of supplies from the bank equal to the sum; this forms their reserves. The player who received the fewest supplies is the first player.

Setup is complete and the game can begin.

On a player’s turn they may take one of two actions: (a) Supplies, or (b) Maneuver; not both in a given turn.

- Supplies: when a player takes the Supplies action, they roll the dice and move their supply token clockwise along the supply sector a number of spaces equal to either die, or the sum of the dice (e.g., a roll of 3 and 5 means the player may move their supply marker 3, 5, or 8 spaces).If the supply marker lands on a space matching its color, the acting player takes a number of supplies (equal to the number of spaces moved) from the bank.If the supply marker lands on the middle space of another player’s home supply area, the acting player takes a number of supplies (equal to the number of spaces moved) from either the bank or that player’s reserves.If the supply marker would land on an occupied space, that move is invalid; the player must choose a different value. If no value available results in a valid move, the supply marker is not moved and no supplies are gained.

If the supply marker lands on any other space, no supplies are gained.

Supplies are limited. If a player would gain more supplies than are available, they take what they can and forfeit the rest. A player cannot gain supplies from more than one location from a single roll (i.e., a player cannot gain supplies from both the bank and an opponent’s reserves on a single roll).

If a player rolls doubles (even if no supplies were gained), they may roll again and attempt to gain more supplies. The player may continue rolling the dice, moving their supply marker, and attempting to gain supplies as long as they continue rolling doubles.

After the player has resolved the die rolls, their turn is over. They pass the dice to the left.

. - Maneuver: when a player takes the Maneuver action, they spend a supply token (returning one from their reserve to the bank), then roll the dice. They choose one of the dice (not both), and must make a number of moves equal to the value of that die. Each move is defined as transferring one army from the space it occupies to an adjacent space (across the sides of the triangle, not through the points).Each army is moved independently and in sequence (they do not move simultaneously). At no time may a space contain more than three armies, even if the army is just passing through. Players may move a single army multiple times, or split the moves between multiple armies. For example, a player who rolls 1 and 5 might choose to make 5 maneuvers; they could move one army five times, or split the moves between multiple armies up to and including moving five armies once each.The player must use all of their moves. If they select a die that rolled a 6, they must make exactly six moves (no more, no less). A player may move an army back and forth between two spaces to use up unwanted moves if desired.After maneuvering armies, if the player rolled doubles, their turn is over. They pass the dice to the left. Also, if the player does not want to spend any more supplies, they may end their turn voluntarily; they pass the dice to the left. As long as a player has supplies in their reserves, has not rolled doubles, and wants to continue maneuvering their armies, they may.

A couple of things before we dive into how armies fight each other:

- A player who takes the Maneuver action must make at least one roll of the dice. They cannot pass their turn without returning at least one Supply Token to the supply bank and rolling the dice. Once rolled, they are bound by the results and must make the appropriate number of “moves.”

- If there are no supplies in the supply bank, and a player has at least one Supply Token in their personal supply, the player must take the Maneuver armies action.

- If there are supplies in the supply bank, and a player has no supplies in their personal supply, the player must take the Gain Supplies action.

- If there are no supplies in the supply bank, and a player has no supplies in their personal supply, the player forfeits their turn and passes the dice to the left.

With all of that in mind, let’s look at how armies fight.

- An army may not cross a terrain marker.

- Armies of different colors can occupy the same space.

- A single army that is in the same space as two armies of a single opposing color is eliminated from the game. Two armies of two different colors (or three armies of three different colors) in the same space are at a stand-off and nothing happens.

- An army (or group of armies) that becomes surrounded is eliminated from the board. In order to be considered surrounded, none of the armies in the target space can have a legal move; if even one of the armies has a legal move, the group is not considered surrounded. The following contributes to a space being surrounded:

- the edge of the board (since nothing can move there)

- a terrain marker (since nothing can pass through it)

- a space with three armies of any color (since the space is full)

- a space with two armies of a single opposing color (since a unit moving into that space would be eliminated as soon as it entered)

In addition to the elimination of armies as described above, Bin’Fa has a pushing mechanism that allows for the advancement and retreat of armies. To do this, the active player must have a space with three armies on it and an adjacent space with two or three armies of opposing color(s). After spending a Supply Token, but before rolling the dice, the player announces their intention to advance their three-Army force into the opposing space. After making this announcement, they roll the dice. If either die is a 6, the advance was successful; otherwise it fails.

- A successful advance means that each army in the target space must retreat to an adjacent space (other than the one from which the advance came). Any army that has no legal move is eliminated from the game. Once all armies in the target space have retreated or been eliminated, the advancing three-army force is moved into the target space. Then, the advancing player must make a number of standard moves equal to the result of the other die – this is the only time a player uses both dice when performing a Maneuver action.If the successful advance was the result of double-sixes, the player has the option of making six standard moves per normal, or performing a second advance with the same three-army force into a space adjacent to the one they just invaded.

- A failed advance means that nothing happens. No armies move and the roll has no effect. As long as the roll was not a double and the player has more supplies, they may continue with their turn (spending supplies and rolling the dice).

A player is eliminated from the game if they are ever reduced to three or fewer armies. All of the eliminated player’s supplies are given to the acting player. The game continues until only one player remains.

In addition to these core rules, the rulebook goes on to explain how alliances and the like are not binding and have no impact on how the game plays from a mechanical standpoint.

Interlude the First

Before we go on and look at how the next edition of the game changes things, let’s take a moment to appreciate what we know of the beginnings of Bin’Fa. The game has a solid core! The board is not very large, but the triangular movement structure makes it seem almost vast. The way the dice are used gives the player agency while restricting their choices; the dice can put a quash on a plan mid-stride, or allow for a bountiful harvest of supplies. The whole thing feels organic, while somehow coming across as alien.

When setting up the board, players build the landscape creating interesting and intricate paths, places where an army could easily get trapped or forced into vulnerable positions. They do this not knowing which region will be their home. Thus, each player has to be careful not to make things too difficult in a region, lest they reap exactly what they have sown.

The rules are solid, but have some odd gaps; the biggest gap being the order in which things happen during the game’s setup. When players are putting their armies onto the battle sector, the rules are silent on how that happens exactly.

- Is it a free-for-all, where players place armies simultaneously? If so, can a player change their mind once an army is placed?

- Is it something that happens in a random order, where one player places all of their armies followed by the next player and so on? If this is the case, doesn’t the player that goes last have a huge advantage, knowing how their opponents are set up?

- Is it something that happens in a random order, where a player places one army followed by the next player and so on until each player has placed all 12 of their armies? This seems the most logical to me, but there is no definitive word on this.

The game uses dice in odd ways. Doubles can be good (supplies) or bad (maneuvers). You are allowed to add the dice (supplies) or not (maneuvers). Once a die is selected, you must use every single pip (supplies and maneuvers)! And so on.

Bin’Fa is a game in which each turn is a gamble. A player must plan for the possibility that each roll could be the last of that turn, or the possibility that every option available to them is sub-optimal; they have to play the odds. While making those calculations, they have to keep their empire fed with supplies if they wish to march their forces to victory.

There are many games where a roll of the dice can result in swings in the action. Everything from Parchesi to the myriad miniatures games available (e.g., Warhammer 40K) have elements like this. In the games of antiquity, the dice were deterministic – there was no point in making plans, because you had no idea what possibilities lie before you from turn to turn; in some games, the dice could drive the action to such a degree that the player is incidental. In the modern era, a well designed game with dice will generally have swings in isolated ways such as when a particular unit scores significantly more or less hits than expected, or when a nigh-impossible result succeeds, or a seemingly trivial roll fails.

In Bin’Fa the dice dictate the exact number of moves a player must make, and the number of supplies (if any) they receive. Neither of these facts sounds as important or as impactful as the dice-related situations described above, but somehow they are! Bin’Fa demands a player have long-term plans while remaining agile enough to improvise short-term solutions to immediate problems. That said, at no time do the dice feel deterministic; the dice are not as restrictive as they are in games like Monopoly or Aggravation. You still have important and impactful choices, it is just that the universe, at all times, is limiting the number of choices available.

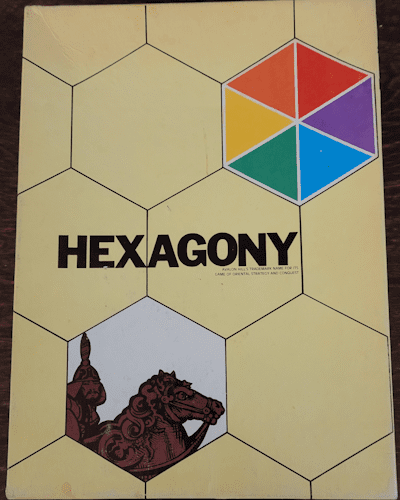

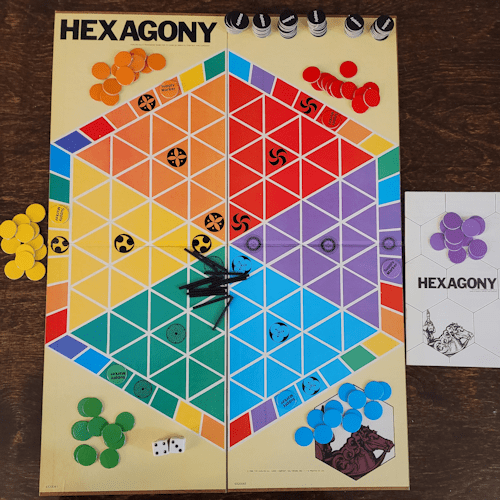

1979 – Hexagony (Avalon Hill)

Avalon-Hill decided that Bin’Fa had some commercial potential. They entered into an agreement with Mr. Hodkinson to produce and distribute the game. One thing they did not like was the name; they asked Mr. Hodkinson to come up with something. Reluctantly, he offered up Hexagony. That, as they say, was that.

I would love to be able to tell you that Hexagony was a gorgeous product with high production values. It was not. Still, I would not go so far as to say it had bad production values, per se; they were what was typical of the time. Where the original 1977 version was an obvious labor of love with wooden pieces that looked like miniature drawer handles and the like, the Avalon-Hill production was, top to bottom, paper-thin cardstock (with the exception of the terrain markers, which remained the same as the original).

The various tokens were colored cardstock circles; but the color was only on one side (all of the tokens were blank white on the back). Tokens that had flipped upside down were completely indistinguishable. During play, this was not a big deal; but when setting up tearing down the game, this proved to be a royal pain in the keister. The cardstock was so thin, it was often difficult to pick up the pieces.

The board was one area where things improved. It was split into two parts so that it could fit into a box with a smaller footprint, and icons were added identifying each faction. In basic play, the icons on the battle sector served no function (they were used in optional rules; keep reading). The icons on the supply sector, however, made the wording of the rule for stealing supplies much easier to phrase.

The rules were kept essentially the same. The following adjustments were made:

- In addition to the Supplies and Maneuver actions, players always have the option of passing their turn and doing nothing.

- When using the Maneuver action, if the player rolls doubles, their turn ends immediately (not after they move their armies). This change cascades into the advance and retreat rules…

- When using the Maneuver action and announcing an advance, rolling doubles (including double-6) ends the player’s turn immediately; the advance fails.

Those last two changes are quite significant!

Mr. Hodkinson, prior to publication of the game, came to like the idea of a stackable checker-like piece for the armies. With such a component, the stacking limit imposed in the original game could be removed (technically, expanded to a 12-army limit). He proposed making some changes to the rules to facilitate this, but Avalon-Hill was not keen on the idea. As a result, the concept was relegated to the back of the rulebook under the heading Optional Rules. This was not the only optional rule included:

- Unlimited Occupation: this was the option that Mr. Hodkinson wanted to make official. The rules for this option include a note that, with the stacking limit removed, armies of different factions can no longer occupy the same space.

- Multiple Factions: in games with two or three players, each player may take on the role of multiple factions. This option includes rules for how to handle supplies, which faction’s armies can be moved on a given turn, and so on.

- Alternate Movement: this is actually two options (that cannot be combined):

- Restrictive Movement: the player can no longer choose which die to use when Maneuvering armies. Instead, they must make a number of “moves” equal to the difference between the die results. For example, a player rolling 2 and 5 must make 3 “moves” instead of being able to choose between 2 and 5 “moves.”

- Greater Movement: in addition to being able to choose which die to use for movement, the player may choose to use the sum of the dice instead. For example, a player rolling 2 and 5 could make 2, 5, or 7 “moves.”

- Headquarters: at the start of the game, each player selects one of the two spaces on the battle sector with their faction’s symbol to be their headquarters. If, at the end of their turn, their headquarters is occupied by an opposing Army, they lose. All of their armies are eliminated and their supplies are given to the occupying faction(s).

- Supply Sector Battles: multiple supply markers may occupy the same space. If a supply marker lands on a space with an opposing player’s supply marker, the acting player may steal supplies from that player equal to the number of spaces moved.

- Trading: players are allowed to trade supplies as part of a deal or alliance.

- The Vortex: in order to play with this option, players would need two copies of Hexagony! Each player controls the same faction on both boards. The game starts with 12 of their armies on each board. The option includes rules governing how to move armies between boards, how to manage supplies, and so on. At the end of this set of rules there is a note indicating that larger games with more copies of Hexagony are possible. One wonders if Marketing added this line to encourage more sales…

- Nuclear Explosions: when attempting to advance, if the advancing player rolls double-6, all armies in both spaces are eliminated and the player’s turn ends.

The rules for unlimited occupation, restrictive movement, and (to in a modified form) the vortex would go on to make appearances in later editions of the game. The rest of the optional rules… not so much.

Sales of Hexagony were never what Avalon-Hill had hoped. They released the copyright back to Mr. Hodkinson in 1986 and Hexagony went out of print.

This was the version of the game I first discovered in 1984. I was in High School and stumbled onto this game while visiting my Friendly Local Game Store looking for role-playing material to add to my collection. As I was looking over the box, the clerk came over and asked if I had ever played. I said no, so he began to describe the game. To be honest, the description was not very interesting. He almost talked me out of buying it.

Almost.

I am so glad I purchased it! Despite the production values and the quirkiness of the rules, my friends and I played this game a lot. I was not the best player in the group. Each time I played, however, the game was different; it felt new.

I was a member of the chess team back then. We would get together to play games (obviously). Hexagony was the only game with dice the hard-core chess players enjoyed. Those guys hated randomness in their games, but the way the dice were used and the way the randomness manifested itself in this game did not bug them at all. Like I said, this game is different.

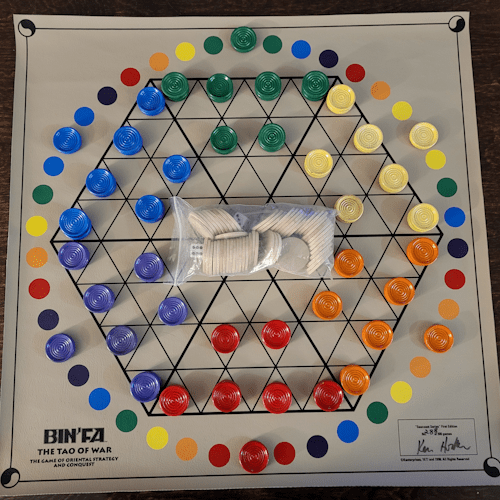

2000 – Bin’Fa Seacoast Edition (limited edition; Kenterprises)

After 14 years of continuing to tinker with the game, Mr. Hodkinson created a new imprint (Kenterprises) and released his limited (again, 500 copies) “Seacoast Edition.” From both a rules and production standpoint, the game changed considerably. The first thing of note was the packaging!

The game did not come in a box, it came in a tube; a rather large tube (24 inches long, 4 inches in diameter)! The components had returned to the aesthetic that made the original release so special: armies and supply markers were painted wooden stackable checkers (in keeping with the desire to remove the stacking limit), supplies were large, chunky wooden disks.

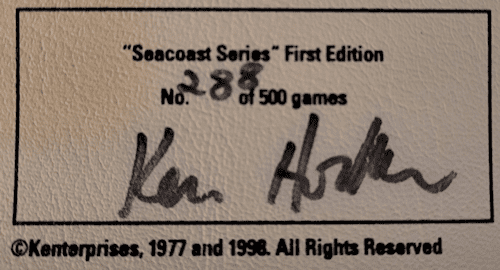

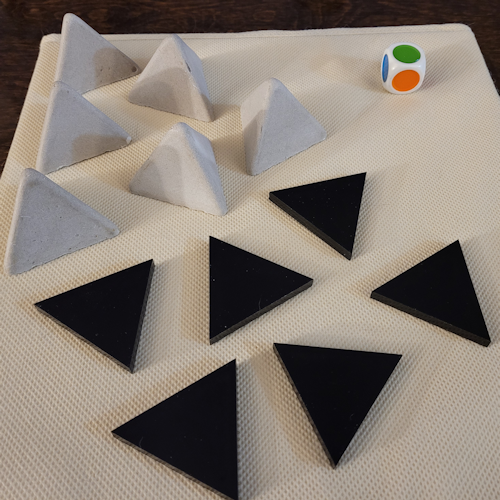

But the truly surprising changes were with the board and the terrain markers.

The board was a vinyl play mat with the familiar hex/wedge/triangle pattern on it. However, the color of each region was gone, replaced with a uniform shade of beige (?). The faction icons were also notably absent. To identify a region, one needed to look at the supply sector and note the color of the home supply area.

The terrain markers were no longer thin black plastic sticks placed along the edges of the triangles. Instead, they were large black wooden triangles that completely filled a space. I have a theory about this: this change may have come about because of the new coloration of the board.

- In previous editions of the game, the battle sector was made up of brightly colored triangles with white-space for the sides. A thin black plastic stick placed along one of those edges would stand out; they were obvious to even the most casual of glances.

- The new board’s battle sector was made up of lightly-colored monochromatic triangles with solid black lines for the sides. A thin black plastic stick placed along one of those edges would blend in; they were all but invisible to anything shy of a close examination.

This is interesting because changing terrain from an element along the edges of the spaces to eliminating spaces altogether has some interesting tactical and aesthetic ramifications. The old terrain markers were subtle. They generated barriers but never removed a space from the battle sector. The new terrain markers were direct. They generated barriers, yes, but each one was like placing three of the old terrain markers around a space (something that would not have been allowed under the old rules). Because they are not subtle at all, the number of terrain markers was reduced to nine. How many you use and who gets to place them is entirely up to the players.

Additionally, the game came with three Vortex Markers. These were large white wooden triangles that completely filled a space. They were the subject of a new set of official rules for the game (more on that later).

The rules of the game were familiar, but most certainly not the same. The degree of change was orders of magnitude greater than the previous transition. Still, the core remained (mostly) intact. The presentation of those rules, however, was quite different. If I am being honest, they are off-putting.

I understand the desire to distance rules from the conventions of old-guard wargaming (an outline format with indexed rule-numbers). I believe these went too far in the other direction. The rules are presented in some sort of quasi-conversational question-and-answer format; it is as if they are lines in a play where one character asks a question and the next rule is presented as an answer to that question. For example:

A: Each player draws a colored piece at random and places the twelve army units of that color on any of the 16 triangles of that army’s home base. A stack of any number of army units (from 1 to 12) may occupy a triangle [Rule 1].

And this is how Rule 1, the rule that establishes the stacking limit for a space at 12 armies, was presented in the rulebook. It is Rule 1 because that was the order in which the question/answer dialog was written. Rule 2 was how to determine the first player. Rule 3 was how to determine how many moves a player must make on a given turn. And so on.

Additionally, the game’s rules were divided into four levels of depth (called stages).

- A new player was expected to start with Stage 1. Only the board, dice, and the armies are used.

- After playing several games at Stage 1, a player is expected to start playing at Stage 2. Terrain markers and the rules for terrain are added to the game.

- After playing several games at Stage 2, a player is expected to start playing at Stage 3. Supply tokens and supply markers are added to the game.

- After playing several games at Stage 3, a player is expected to start playing at Stage 4. Vortexes are added to the game.

As I said above, the rules changed a lot! None of the changes were what one might call drastic (except, perhaps, the vortex rules and the movement rules for stacks of armies). This was still Bin’Fa, but not the Bin’Fa of yesteryear. What changed, you ask?

- Stack Movement: all or part of a stack of armies can be moved as a single unit, using one move. This means individual armies are no longer the basis for a given move; one move can impact any number of armies in a given stack.

- Restrictive Movement: the restrictive movement optional rules from Hexagony became the official rule.

- Assimilation: two odd rules were added splitting the difference between old and new thinking:

- armies cannot enter into a space containing two or more armies of a different faction.

- an army can enter a space that contains a single army of a different faction. When this happens the moving army is stacked on top of the original army. The original army is now considered as if it were of the moving army’s faction. This will remain the case for as long as an army remains stacked on it.

- Immediate Effect of Doubles: when rolling doubles while performing the Maneuver action, the player’s turn ends immediately. This is not a change; but it is interesting to note that the rationale for the rule became clear. Since the restrictive movement rule was now official, rolling doubles results in 0 moves being granted (the difference between the die results is zero).

- Advancing armies: with the stacking limit increased to 12, the rules for advancing and retreating needed to be rethought. Several things changed here:

- To advance a stack, it must contain more armies than the stack it is attempting to dislodge. The exception being that a stack of 12 armies can attempt to dislodge any opposing stack.

- If a six is rolled, the advance was successful; the defending stack must retreat and the attacking stack enters the vacated space. The attacking player then performs regular moves per the standard rules (the difference between the dice).

- If a six is not rolled, the advance fails and no moves are made. Provided the roll was not a double, the player may continue.

- Rolling double-6 on an advance does not cause it to fail! Instead, the defending stack must retreat twice; the attacking stack enters the second vacated space. No normal moves are taken (since the difference between the dice is zero).

- One Source of Supplies: when a supply marker lands on the middle space of an opponent’s home supply areas, that player gains supplies from that faction equal to the number of spaces moved. They do not have the option to take supplies from the bank in this case!

- The McCallion rule: a player gains supplies from the bank when their supply marker lands on a space of their color, and when their supply marker lands on a space of a color matching the color of a region in which they have one or more armies.

- The Vortexes: unlike the Vortex optional rules from Hexagony, the Vortex Markers in this edition of the game did not require multiple copies of the game. They were, instead, an advanced rule to be used when players had become comfortable with the basic rules (Stages 1, 2, and 3).

- Vortex markers are placed on the board after terrain markers, and in much the same way.

- While players can agree to use fewer than the nine terrain markers provided with the game, it is important that if vortex markers are used, all three are placed on the board.

- When an army enters a space with a vortex marker, the army is immediately teleported to one of the other spaces with a vortex marker. An army teleported this way cannot move until the player rolls the dice again. Each army that enters a vortex space can be teleported to either of the other two vortex markers (a single stack that enters can be split into two stacks, one on each of the other vortex markers).

- On the player’s next roll of the dice, provided they do not roll doubles, using a single move allows all of the armies in a stack on that vortex marker to move to an adjacent space as long as that constitutes a legal move.

- On the player’s next roll of the dice, if they do roll doubles (or if they have armies on two vortex markers and they only get one move), any armies that remain on spaces occupied by vortex markers are eliminated from the game.

- All armies in a stack that retreat into a space with a vortex marker are eliminated from the game.

- If a player is eliminated because of losses stemming from a vortex marker, their supplies are returned to the bank, not given to another player.

Whew! Yea, I get it: walk away for a moment and take a breather. That was a lot of adjustments to take in; but remember – these changes represent 14 years of tinkering. Mr. Hodkinson continuously sought to move his creation closer and closer to perfection. In his pursuit, he was not unwilling to listen to constructive criticism. Consider, for example, the case of John McCallion.

Back in the day, John McCallion was a writer/reviewer for Games magazine. His review of Bin’Fa (Hexagony?) was quite positive. He did, however, make two interesting observations:

- Players need supplies; getting them is not easy (based on how often a color appears on the supply sector). Thus, players tended to spend far too much time attempting to gain supplies.

- One successful strategy involves doing very little other than attempting to gain supplies. A player can place their armies and then leave them in their home region, using every turn to gain supplies. In this way, they force their opponent(s) to spend supplies coming to them. Eventually, the player utilizing this strategy accumulates so many supplies that the bank is exhausted; their opponent(s) can no longer move…

Mr. Hodkinson created one simple rule that fixed both issues! This is the McCallion rule, above. One very simple rule simultaneously encouraged players to engage with one another, while reducing the amount of time needed to keep their empire supplied. It was brilliant.

Interlude the Second

The Seacoast Edition was released 14 years after Avalon-Hill stopped publishing Hexagony. The final version of the rules would take another 14 years to be realized. But for me, the next step in the journey would be a random, highly improbable encounter that would take place in the mid-to-late 2000s. That encounter should never have happened.

There is an old saying: fact is stranger than fiction. The reason: fiction has to make sense, fact does not.

The facts are these: I was in the United States Navy from 1987 to 1997. During that time, I played a lot of role-playing games, designed a few board games, and (in the 90s) played a lot of Magic: The Gathering. By the end, I had not quite left the board gaming scene, but it was close. Some time after I left the Navy, I met up with some good friends and started to become aware of the renaissance in board gaming that was taking place. Thanks to BoardGameGeek (member since 2003), I was discovering more and more. It was not long before I was accumulating a sizable board game collection!

With the aid of the internet and the growing influence of sites like eBay, I was soon able to locate older games that I had loved in my younger days. I found a couple of auctions for copies of Hexagony and I was able to own it again (I managed to snag both copies).

When I first started searching for Hexagony, I kept getting results for this Bin’Fa thing. At first it was annoying and I figured I was structuring my search incorrectly. But after a while, it started to sink in: these were the same game. So I started searching for Bin’Fa. That is when it happened.

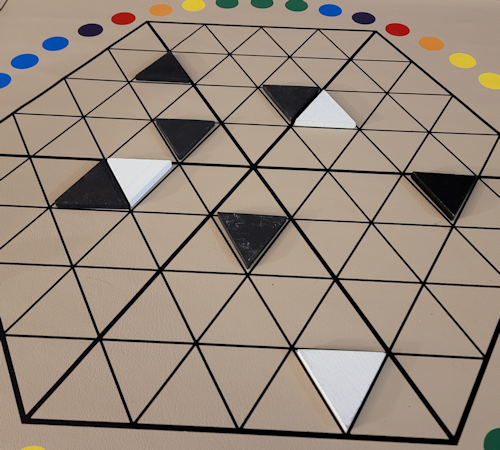

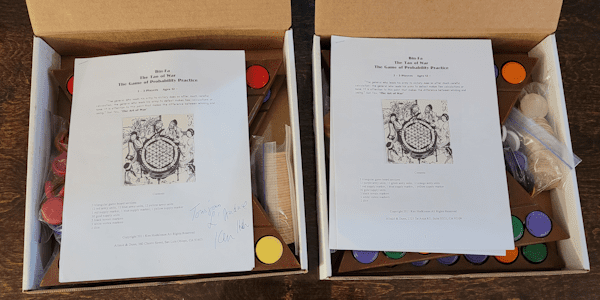

One of the results in my search was this website that appeared to be a religious site for Taoism. On the site, I located a link to Bin’Fa, and clicked on it. The page was a discussion of the game. There was (if memory serves) a form to order a copy of the game, hand-crafted by Ken Hodkinson himself. I was overjoyed!

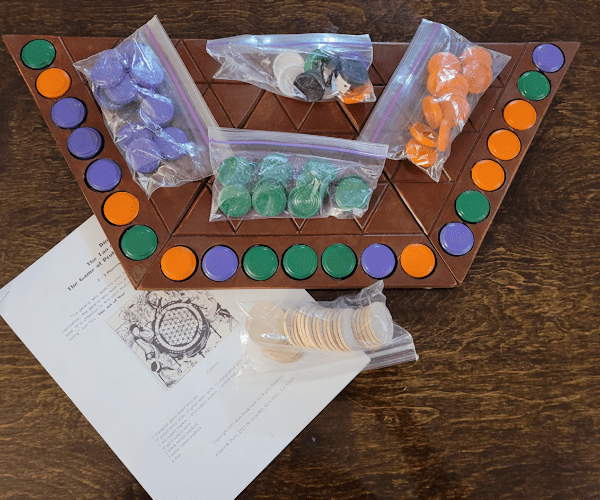

I could not get the form to work. So I clicked on an email link and wrote a message to the email address provided on the page letting them know the form was not working, and that I was interested in getting a copy of the game. One of the things I noticed was that this new version appeared to have a modular board, where each region was separate. The page suggested that this was only three colors. So in my email I asked if it would be possible to order two copies with the second copy being three additional colors so I could have the whole six-player experience again. Without much further thought, I clicked send and awaited the response.

A few days later, I received an email that was an expression of pure confusion. The individual who responded (Mr. Hodkinson’s daughter) started by asking how I had gotten to the website, since it was not yet live. It was not supposed to be reachable from the outside. When I read that part, I went back and checked; she was right, I could not get to the site I had seen any longer.

She went on to say that it was true that her father was working on these hand-made sets, but that they were not yet ready to put them out into the world. However, since I had managed to find a non-extant website, perhaps it was fated that I receive a copy of this new version. She sent me instructions on making my payment for two sets in a total of six colors. I wrote back, thanked her profusely, and sent off the money. It was a couple of weeks later that I received my package.

There are things I own that are extremely meaningful and that I treasure. Few can compare to how special these two boxes make me feel.

Had this been the version that went to market, then each copy would be a unique expression of the game. I am sometimes saddened that this was not the actual commercial release.

For this version of the game – and I must stress, this was never published – it appears to have been designed exclusively for a 2-3 player experience. The supply sector only has the colors of the three factions included in that set. This means that if you combine the sets, then half the supply sector will not have the color you are looking for.

But let’s talk about the rules. They have the most significant changes of any set that has come since the original game; changes that will remain with the game into its final form (keep reading!). The biggest change being the board. At some point in those 14 years, Mr. Hodkinson had a moment of clarity: there is no reason why the shape of the board has to be a hexagon; there is no reason why the shape of the board has to be fixed.

By separating the regions into individual triangles and allowing the players to arrange the boards in any pattern they wish, uncountable possible configurations of landmass and terrain features could be imagined with this game.

This change alone would be worthy of a new edition. But Mr. Hodkinson was not finished. In addition to the modular board, the changes include:

- Each set was for up to 3 players; thus each set comes with:

- Three board segments

- Three terrain markers (black checkers)

- Three vortex markers (white checkers)

- 13 armies in each of three colors

- 1 supply marker in each of three colors

- 30 supply tokens (half of what came in the old sets; still 10 tokens per player)

- Two six-sided dice

- Rules for the supply sector (i.e., how to move from the supply sector of one board segment to the next).

- Players may no longer pass their turn if they or the bank has supplies.

- The McCallion rule remains, but was updated slightly. A player gains supplies when their supply marker lands on a space that matches a color where they currently have armies. This includes their home sector: they do not gain supplies when landing on their own color unless they currently have armies in that sector.

- When attempting to gain supplies, players may move their supply marker a number of spaces equal to one of the dice; they may not add them together.

- When attempting to gain supplies, if a player’s supply token lands on the middle space of an opponent’s home supply area, they have the choice of gaining supplies from that player’s reserve, or the bank (restoring the ability to gain supplies from the bank in this case).

- A stack can attempt to perform an advance onto an opposing stack from the vortex space as they leave. This is exceedingly dangerous!

- The rules include a new piece: the general. This piece occupies a space by itself, and is treated as a stack of 12 armies. A general may advance on any stack; it cannot be forced to retreat.

The rules changes, other than those resulting from the inspired choice to separate the board segments, are quite minor. They are tweaks, adjustments, and streamlining. They are very, very close to what the final state of the game would be.

There was one major omission in this edition: nothing in the rules speaks of a game with more than three players. Nothing at all. The rules do not even hint at the idea that there might be another set with three more colors. With nothing to go on, there are some ambiguities. For example: the Seacoast Edition had five of the new-style terrain markers. Each of these half-sets has three such markers. If you combine the sets, do you use five, or all six? The same question applies to the vortex markers. The Seacoast Edition had three of these and indicated that all three should be used. Each of these half-sets has three such markers. If you combine the sets, do you use three, or all six?

These are not major questions, but they are odd omissions. And the answers to them, as presented in the final rules, might surprise you!

2014 – Bin’Fa (Kickstarter; Taoist Arts Foundation)

The final rules and basic production (the physical form) of Bin’Fa would be the Kickstarter edition of the game from 2014. The final product would be produced in 2017 (an aesthetic upgrade pack for the Kickstarter edition to give the components a little more je ne sais quoi). The campaign ran in November and December of that year; delivery was scheduled for February the following year. As with many campaigns, delivery was delayed; but Mr. Hodkinson kept up good communications with the backers, and things went smoothly and cordially. By all accounts, backers had their games no later than June 2015.

I originally pledged in this campaign. But my life had reached a chaotic storm level of uncertainty, and so I had to cancel my pledge. Mr. Hodkinson’s daughter reached out to me and asked why I canceled my pledge. I explained my situation to her, and she expressed her sympathies.

A few months after the backers of the campaign received their copies of the game, I received two things in the mail. The first was a copy of the Seacoast Edition of Bin’Fa (the one pictured above), the other was a copy of the Kickstarter edition. I wrote back to express my extreme and sincere gratitude. Later, when my life settled down, I would attempt to pay for those gifts; no avail, she would not let me. So, instead, I purchased two more copies of the Kickstarter edition (one of which remains in the shrink wrap to this day), and I purchased a couple of copies of the upgrade pack.

I also wrote a booklet called A Collection of Possibilities which attempts to distill the game down to its most basic form (armies and supplies), then treats every other element of the game as a module that can be added or left out. I even included a few of my own ideas in there. When I wrote to ask Mr. Hodkinson if he would mind my posting those rules on BoardGameGeek as a free download, the response was that he loved it and wanted to host them on the official Bin’Fa website as well (the page with the link and description can be found here).

So what all changed in the Kickstarter edition? From a rules standpoint, not much if you had experienced the prototype…

- The modular board was kept from the prototype version; the color distribution for the supply sector was altered somewhat to account for the assumption of six board segments.

- The number of terrain markers was increased to 6. The rules indicate that the players decide during setup how many will be used (i.e., 0 to 6 terrain markers).

- The number of vortex markers was increased to 6. The rules indicate that, like terrain, the players decide during setup how many will be used (i.e., 0, or 2 to 6 vortex markers).

- The rules for gathering supplies revert back to allowing a player to use the sum of the dice.

- The McCallion rule is reverted back to its original state. A player gets supplies when their supply marker lands on their own color, even if they have no armies in their home region.

- The General from the prototype rules is included. In this edition, it is a pawn, so it is distinct from the regular armies.

- The rule for eliminating a player changes. To remain in the game, a player must have at least four armies, or two armies and a general.

From a production standpoint, no matter what your last experience of the game had been, quite a bit…

The components include:

- 6 region boards

- 12 armies of each color

- 1 general of each color

- 1 supply marker of each color

- 60 supply tokens

- 6 terrain markers

- 6 vortex markers

- 2 six-sided dice

The faction boards are good quality. They are thick enough to be quite functional and not warp over time. The other components are all light-weight, inexpensive plastic. The armies, terrain markers, and vortex markers are all generic stackable checkers. The generals and supply markers are basic chess pieces (pawns and bishops, respectively). The supply tokens are non-descript plastic discs (they are much smaller than the old wooden discs, and are thick enough to be easily handled in play). Overall, it is what one would expect from a campaign that was asking for just $2,000.

Purchasing the upgrade pack added a few interesting elements:

- A set of stickers to be placed on the army checkers; these add the faction symbols.

- 6 large terrain markers that look like pyramids or abstract mountains.

- 6 shiny black plastic vortex markers

- 1 weather die

Only the weather die has its own rule:

- At the start of a player’s turn, if they selected the Maneuver action, they roll the weather die at the same time they roll the other dice. No movement can take place in the region of the color that comes up on the weather die.

I have to say, in practice, that weather die can shut down a working plan pretty darn quickly!

Not long after the upgrade pack became available, it was included in all of the commercial packages – you get both when you buy the game. The only place you can get it now is on the Bin’Fa website.

Interlude the Third

The sheet that comes with the upgrade includes a story about how there is a major flaw in the game. During a Bin’Fa tournament that Mr. Hodkinson supervised, two players in the third round were all that remained. Each had four armies, meaning they both were still technically in the game, but the idea of getting their opponent into a position to reduce them further was virtually impossible. The solution that was envisioned was, well, not good.

The rule proposed was to have the loser of the game pay a sum of money to the winner based on the number of supplies that accumulated over the course of the game. The cost per supply token would be agreed upon prior to game play. The rationale was that Bin’Fa was a game with analogs to real warfare, and real warfare is expensive.

There are two things wrong with this:

- Gambling is illegal in some places and depending upon the amount owed, this could run afoul of the law.

- The rule does not fix the issue. In the case of the tournament, for example, who lost? Who would owe who money?

Sometimes games end in stalemates. This includes great games! Once you see stalemate as a feature and not a flaw, it no longer needs to be fixed. This has been my view of this from the beginning.

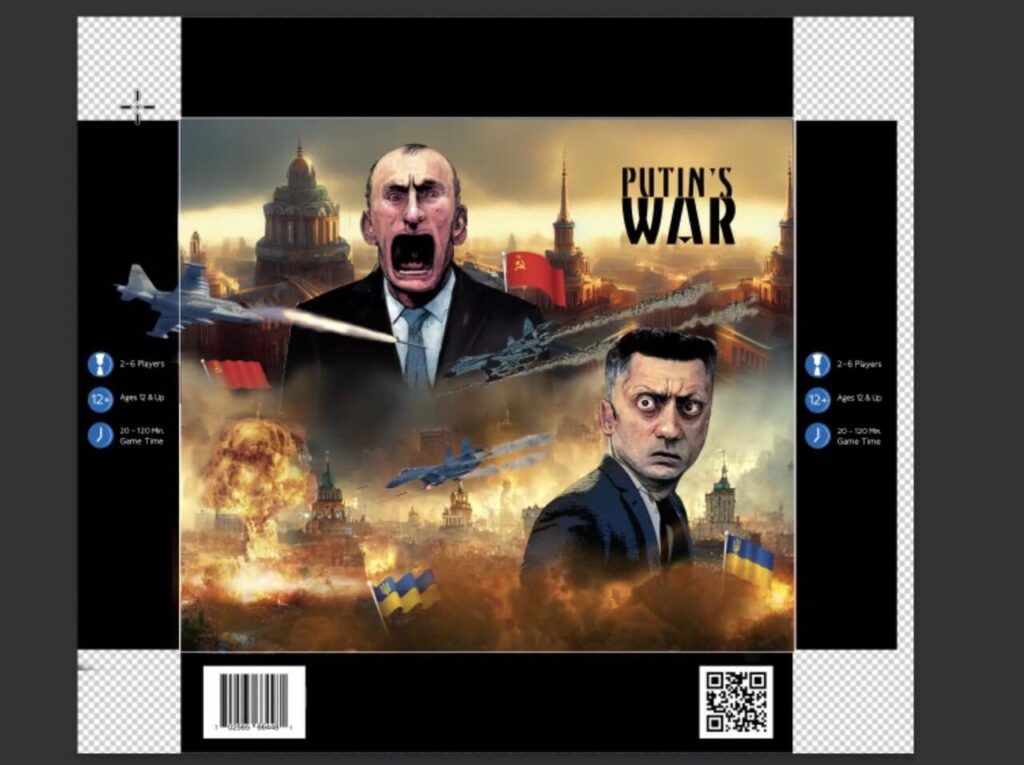

2024 – Putin’s War (Meeple Mountain)

While I was going through my notes and putting this article together, I reached out to Mr. Hodkinson and his daughter. I wanted them to look over what I had written and ensure that I had not missed anything, misrepresented anything, or just plain messed up in any way. The response I received was amazing! Not only were they delighted at the idea of the article before they read it, they were equally delighted by what I had written. They helped me with a couple of facts (such as the inclusion of the upgrade pack with all current copies of the game). Then came the surprise! Mr. Hodkinson created a topical variant of the game based on the Ukrainian conflict.

The idea was to package it in a new box, with a new name. But that, sadly, appears unlikely at this point. This is an image of the box art that was created for this product:

Putin’s War plays with the core rules from the 2014 edition, with the following modifications:

- This is a two-player game using all six armies.

- Ukraine plays the blue and yellow factions; those segments should be adjacent to one another.

- Russia plays the green, orange, purple, and red factions; those segments should be adjacent to one another.

- Each of the factions is given 8 supplies at the start of the game.

- Play starts with Russia, then alternates players.

- At the start of each turn, the player chooses which of their factions will be active. Supplies or movement is restricted to that faction only.

- The weather die is used, but only by Russia, and after they have chosen which faction is active (this is their disadvantage, making up for the extra forces they have available).

Otherwise, all rules from Bin’Fa apply. Vortexes in this game represent tunnels and air-drops. Although the larger forces of Russia might seem one-sided, in play-testing, it was not! The games that they have played testing out this idea were close, tight games.

Final Thoughts

Ken Hodkinson created the core concepts that would become Bin’Fa in 1971. He worked on those concepts until he had a viable product, which he brought to market in 1977. A respected game company saw potential and partnered with him in 1979, producing the game until 1986. Mr. Hodkinson continued to tinker with the rules over a 14 year period when he released an updated version in 2000. He then continued to tinker with the rules over another 14 year period before running a successful Kickstarter campaign in 2014 to release another edition (the rules of which were based on a prototype he was working on privately). Finally, in 2017, with some upgraded components, he added the final rule to the game: weather. In 2024 I have been blessed with the permission to bring to you his latest variation on the game, Putin’s War. At some point (I am not exactly clear as to when, exactly), the rights for Bin’Fa were set up in such a way that all proceeds went to the promotion of Taoism. Which, I have to say, is one of the aspects of this story that warms my heart.

Now we know and understand the history of the game. So, what is Bin’Fa, exactly?

The initial gut response might be to say that Bin’Fa is an abstract strategy game that incorporates wargame-like elements (logistics, terrain, and even magic or technology, depending upon how you want to interpret the vortex rules). But even this seems to miss the mark.

It is not like classical board games. The board is not static like it is with Chess or Go. It goes well beyond the typical restraints of a wargame: the rules have used two very different forms of terrain over the years, and now has a board that need not look anything like it did the last time you played. All of this gets us close to an answer, without quite getting the job done.

The problem with answering this question is that we are starting with a false assumption. We are assuming that Bin’Fa is a game. Bin’Fa is not a game.

It has taken me a long time to figure this out. Bin’Fa is a game family; a game system. The core of the system is in the separation and interaction of the supply and battle sectors. Everything else is window dressing. The two things that finally convinced me of this were the work I put into making the A Collection of Possibilities booklet, and my seemingly unending examination of the evolution of the rules of Bin’Fa.

Yea, read that again – I cannot tell you the sum total of hours I have spent looking at the various stages, versions, and combinations of the rules that have occurred between editions. In some years, it has become almost obsessive. I love this system! I love its history! Specifically, I love…

- …how the stacking limit for armies (seemingly set by the number of pieces that could physically fit into the original triangles and nothing else) morphed when Mr. Hodkinson got the idea to use checkers instead of non-stackable button-like pieces.

- …how the change in the stacking rule cascaded into the elimination of the stand-off rule (where armies of opposing factions could occupy the same space), and the rules that allow a single army left alone to be permanently captured.

- …how an odd-ball optional rule in Hexagony that required the players to own multiple copies of the game was reworked into the modern vortex rules.

- …how a shift in the coloration of the board seems to have resulted in a major shift in how terrain is defined and used.

- …how the parameters of the game’s setup are all in flux: how many terrain markers to use? How many vortex markers to use? How do we put the board together? And so on.

- …how even the most basic of rules can be slightly shifted into a strange new design space (e.g., that glorious optional rule for supply sector battles).

- …how some elements of the game appear to have been born of Mr. Hodkinson’s random thoughts (the general, the modular board).

- …so much more about this experience.

There have been four commercial releases of the game (1977, 1979, 2000, and 2014). In each release, some rules were tweaked and adjusted, while others were completely overhauled. Some have gone back and forth over time. Each of these versions are related in much the same way that 500 Rummy, Gin Rummy, Canasta, and Mahjong are related. Same family of games, very different experiences.

If you don’t believe me, ask yourself: what is the right way to play Bin’Fa?

- If I prefer the 1977 version and continue to play with those rules, using my Kickstarter edition components, am I playing Bin’Fa correctly?

- If I use a combination of the new and old terrain markers in the same game, or use a combination of the optional rules from the Hexagony edition, am I still playing Bin’Fa?

The answer here is yes! You are playing a game in the Bin’Fa family and you are playing it correctly.

Bin’Fa is a beautiful system with many, many options and modules that can be incorporated or ignored as desired. Its core is strong and flexible enough that it can, at any time, literally be the game you want it to be, while remaining true to a framework that makes every option feel like it belongs.

I know that much of my love of Bin’Fa has nothing to do with how good or how fun it is. It is both good and fun, but I realize that I have fond memories, a history of interaction with the designer and his family, and the joy of tinkering with the system myself all clouding my view. When I look at any of my nine copies of this game, I see them through the rosiest of rose-colored glasses! Bin’Fa is wonderful, and I love it despite all of its various shortcomings. For a game system that feels like it was born in the same breath as Go, I believe that to be high praise, indeed!

Wow- What a fabulous and detailed article about Bin’Fa and its incredible evolution. Thanks for posting!

Erika,

I will be in San Diego on March 6th and 7th. If you and/or Ken are still in the area and you are around, we could possibly connect. You may still have my e-mail if you would like to get in touch.

Mitch

This is superb review. I also have a long history with Bin’Fa. Many years ago, I wrote about that history in a review for The Games Journal. I might be able to find it on an old computer. I can send it to you if you like, although Ken and Erica may have it. I discovered Bin”fa at Games People Play in Cambridge, Ma in 1977. It revitalized my childhood interest in board games. I contacted Ken who miraculously called me as I was playing the game several weeks later. And then, many years after that, Ken was visiting some friends in my home town of Dublin, NH and we got together for a game. It’s been several years since we’ve been in touch. Like you, I have every version of the game, except the Avalon Hill one which seemed unnecessary. I’m so glad that you wrote this comprehensive article and you’ve inspired me to get Bin’Fa out again soon!