‘Neath the Eyeball of Saint Isidore

We all had to memorize the opening of Chaucer’s General Prologue from Canterbury Tales, right? Eighteen lines of Middle English poetry—and one gigantic run-on sentence at that! English teachers love that sort of thing. For those who may have forgotten or been spared altogether, I’ll summarize. It’s April and Nature has pricked the conscience of various pilgrims to strike out on the road toward Canterbury to make all matters of the soul right once again.

Such is the setting of the 2011 classic The Road to Canterbury. Upon reading that designer Alf Seegert’s graduate degrees include both Philosophy and English, the subject material and its treatment suddenly makes sense. The road is darkly endearing, a demonstration of more than a working knowledge of Mr. Chaucer with just enough humor to be approachable.

Where Chaucer introduces two dozen (or so) pilgrims, Seegert’s creation zooms in on one—the Pardoner. The game is limited to either two or three players, both or all of whom assume the role of a Pardoner straddling the penitential fence. The two tasks at hand are to tempt pilgrims unto one of the seven deadly sins while simultaneously taking a financial interest in issuing something of a bogus absolution. There are Relics to relish. Sinners will die. Someone will be declared the greedy victor.

Via the Writing Quill of Saint Anselm

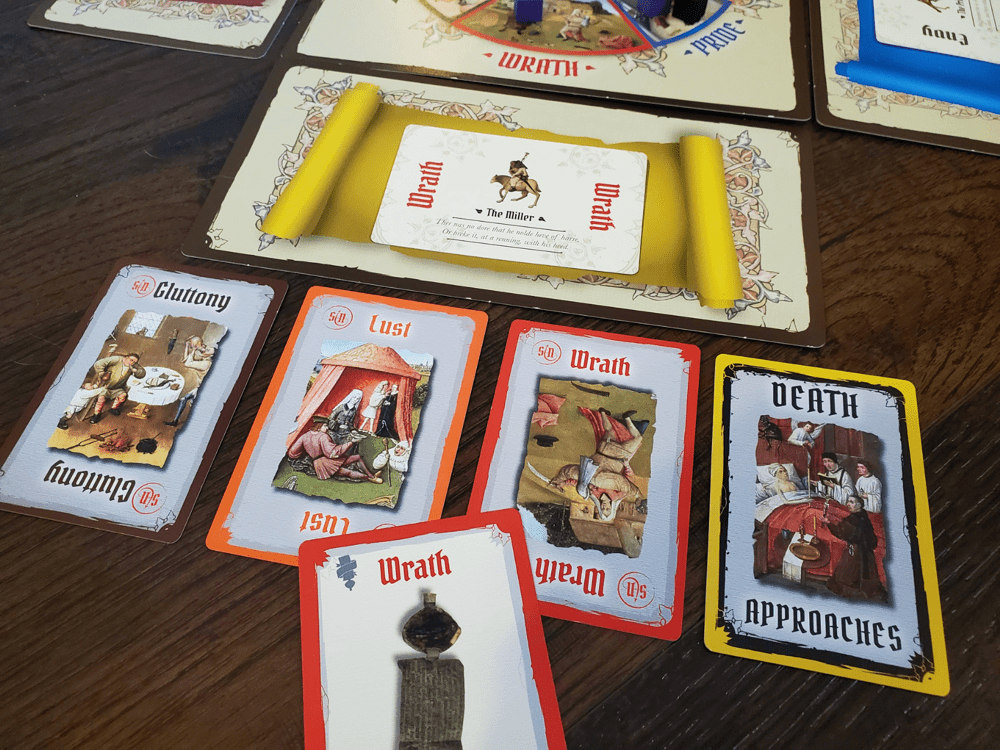

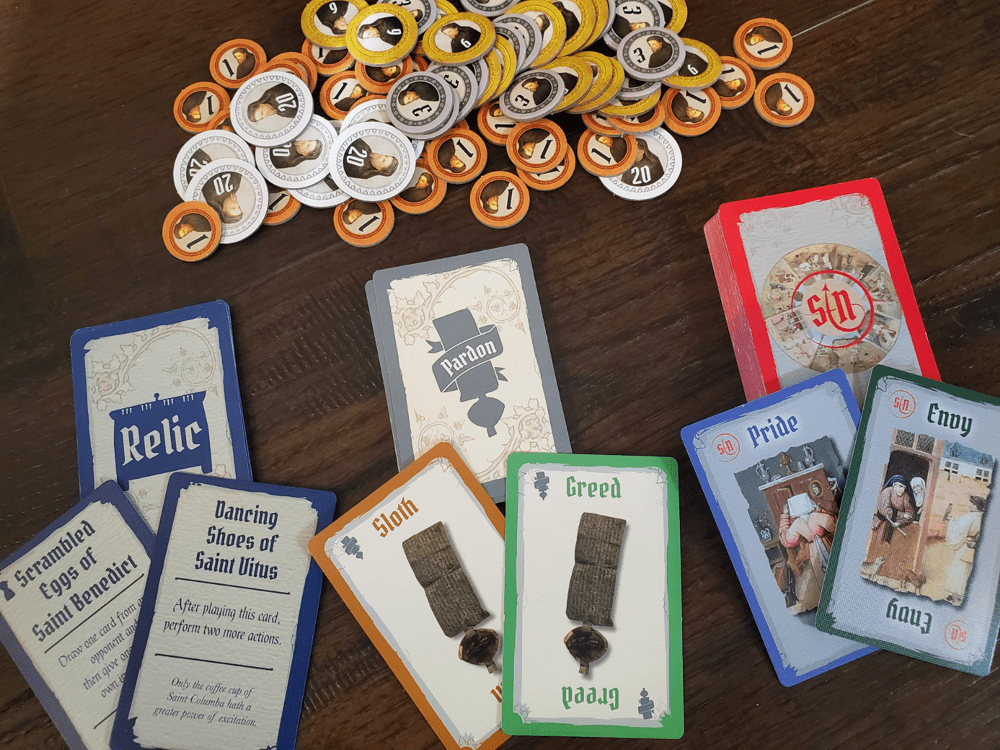

Throughout the game players work from a hand of five cards, with a turn consisting of playing a card and drawing back up from one of three decks. Sin cards each depict one of the seven deadly sins that push pilgrims toward death. Pardon cards are used to pardon the deadlies in exchange for coins. Relics offer single-use abilities to enhance the experience.

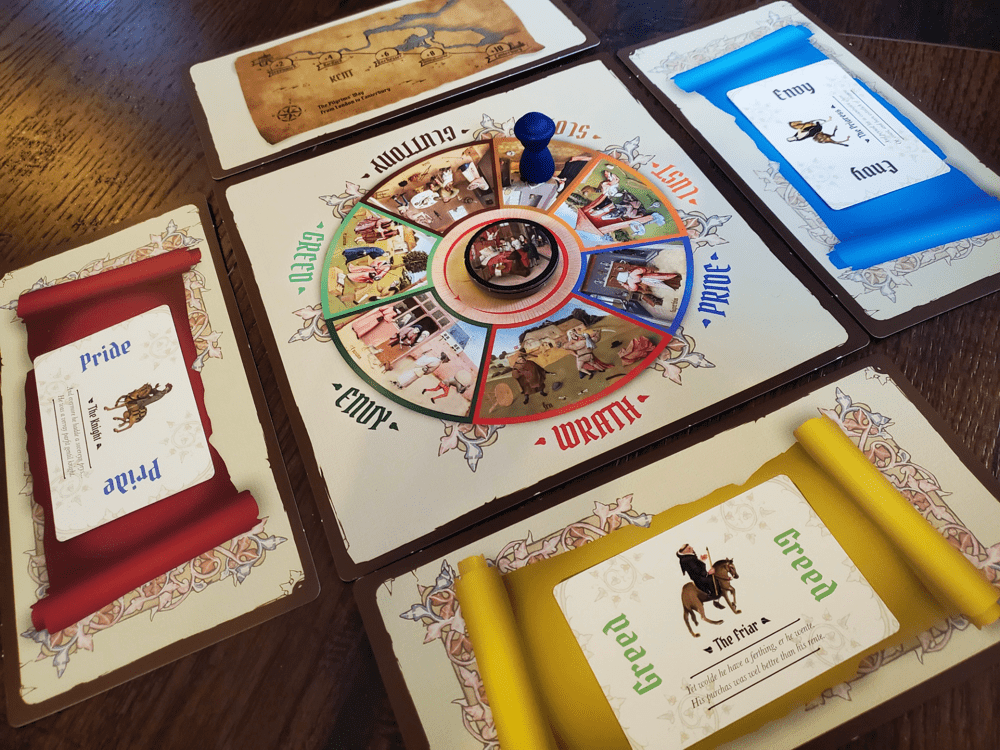

The central play area is made up of five “boards” laid out in a cross pattern, though they are sturdy cardstock rather than cardboard. The center is a wheel o’ sin where players track, via cubes, all the types of Sin cards they have played. Players receive a bonus in order if and when they distribute all seven of the sins.

Around the wheel, there are three pilgrim companies, each with a card featuring another of Chaucer’s famous pilgrims and their pet sin—the Wife of Bath and her lust, for example. These companies are the foreground of the struggle as players tempt the representative pilgrims to sin by placing Sin cards beneath them.

When a Pardon card is played, all the copies of that particular sin beneath that pilgrim are flipped to their backside and the player is paid based on the number of matching cards. Should the Parson pawn, which moves about the wheel o’ sin, be marking and condemning that particular sin, he counts as an extra card for payment. With each Pardon card, players also place a cube on the pilgrim company, indicating their questionably useful ministry there.

The tension along The Road to Canterbury comes from the fact that a pilgrim dies when a seventh Sin card is laid beneath them. This could happen somewhat randomly as a result of a Death Approaches card. When these cards are drawn, they are simply added to the corresponding pilgrim company and serve as wilds matching that pilgrim’s pet sin. One or more of these could easily push a pilgrim to the grave.

If a player intentionally serves up the final sin, they are rewarded with a Last Rites token due to their being present to minister in the throes of death. Last Rites tokens can be spent for an additional action during a future turn or held for a few points at the end.

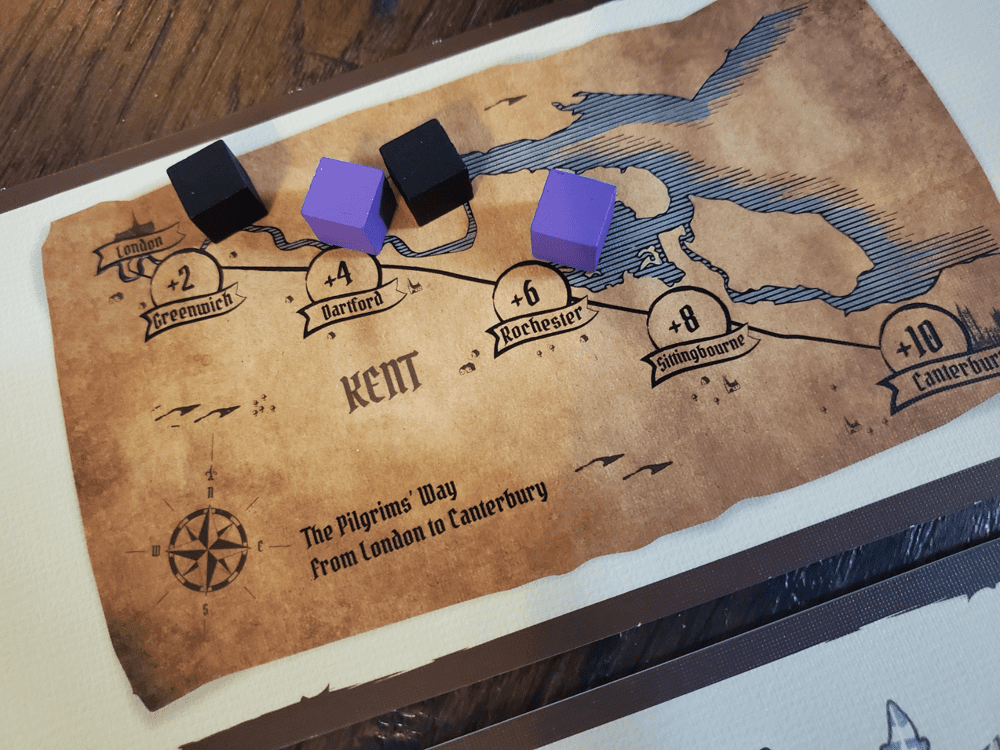

When a pilgrim dies, the player(s) who pardoned that pilgrim the most sends a cube to the map—the fourth of the central boards. Five pilgrims will die in each game and each successive location on the map is worth a few extra coins. At the game’s end, much like the central wheel, players receive bonuses based on their accumulated presence on the map. The cubes that are left behind following each death remain with the three pilgrim companies for yet another scoring spread in the endgame.

When the fifth pilgrim is buried, the game ends after the final bonuses. The player with the most coinage wins.

Under the Moustache of Saint Wilgefortis

One game that has tickled my fancy over the past year is Petrichor, an area control struggle that takes place via rain in the sky, on the field, and on a meteorological sideboard. In that clouded affair, each battlefield communicates with each other, though at a wonderfully disjointed pace, to create a tapestry of varied tensions. I get similar, but simpler, vibes from The Road to Canterbury.

The beauty of Alf Seegert’s design is in the layered competition space. The central wheel o’ sin gives 20/10/5 mid game coins to the players who diversify their temptations by laying different Sin cards. The map grants the same endgame spread to those who achieve the greatest overall influence over dying pilgrims. Each of the three companies offers 15/7/3 to the players whose pardoning presence was strong enough to leave traces behind even after pilgrims stepped toward the light. All of this takes place through the simplicity of “play a card, draw a card” mechanic and the stress of a seven sin limit.

One turn might present multiple pardoning opportunities—one paying out more up front, but the other coming with much needed influence over the prideful Knight who is near-ready to kick the bucket with six sins.

The next turn might feature a life-or-death decision. Should I lay out my sixth deadly Sin on the gluttonous Monk for the sake of filling the wheel, or should I play the final temptation to the wrathful Miller for a Last Rites token? I want the center points, but if I let him live, my opponent, who is clearly holding three Pardon cards, might be gearing up for a profitable turn. Oh, the agony of false piety!

To some, the idea of juggling multiple area battles with staggered scoring triggers might sound like torture. It is music to my ears. I love racing for one area while trying to effectively saturate another area so that I can slowly trickle into a third area.

The card backs are always visible along this road, creating a puzzle of partial information. I can see that my opponent’s hand consists of two Sins, two Pardons, and one Relic, for example. Better yet, maybe they hold no Pardons and therefore cannot interfere with the next step of my current scheme. The puzzle adds to the decision-making process.

The Death Approaches cards add random disappointment while occasionally accelerating the game’s pace. In a twisted way, I enjoy watching them appear out of nowhere, claiming the life of my envious Prioress before I get the chance to pinch her last few coins. There’s a whimsy to it all that I’m perfectly OK with. I’ll just get the next pilgrim.

The Relic cards then fill that final piece of the strategic pie. Playing the Knickers of Saint Nicholas as a wild Death Approaches card, then following it with a bonus Pardon card, might be a lucrative combination. Using the Dancing Shoes of Saint Vitus to play two actions instead of one might swing the balance of cubes on multiple pilgrims near the end. Employing the Collar of Saint Bernard at the right moment might eliminate every other copy of a Pardon you’re hoping to issue on your next turn. The Fingernails might not really have belonged to Saint Vincent, but they’ll get the job done, if you know what I mean.

By the Hairbrush of Saint Hildegard

The 2nd Edition of the 2011 production is pretty much exactly what I would want it to be. The artwork—from the Sin cards to the central wheel to the delightful box—is reminiscent of the irreverence of Monty Python, which keeps the mood light. The cards and the cardstock “boards” boast a lovely quality (even if they aren’t as hefty as the original). The cardboard coins are quirky with their iconic style of imagery. The cubes are cubes. The box is more than double the size it needs to be, but it’s suitable.

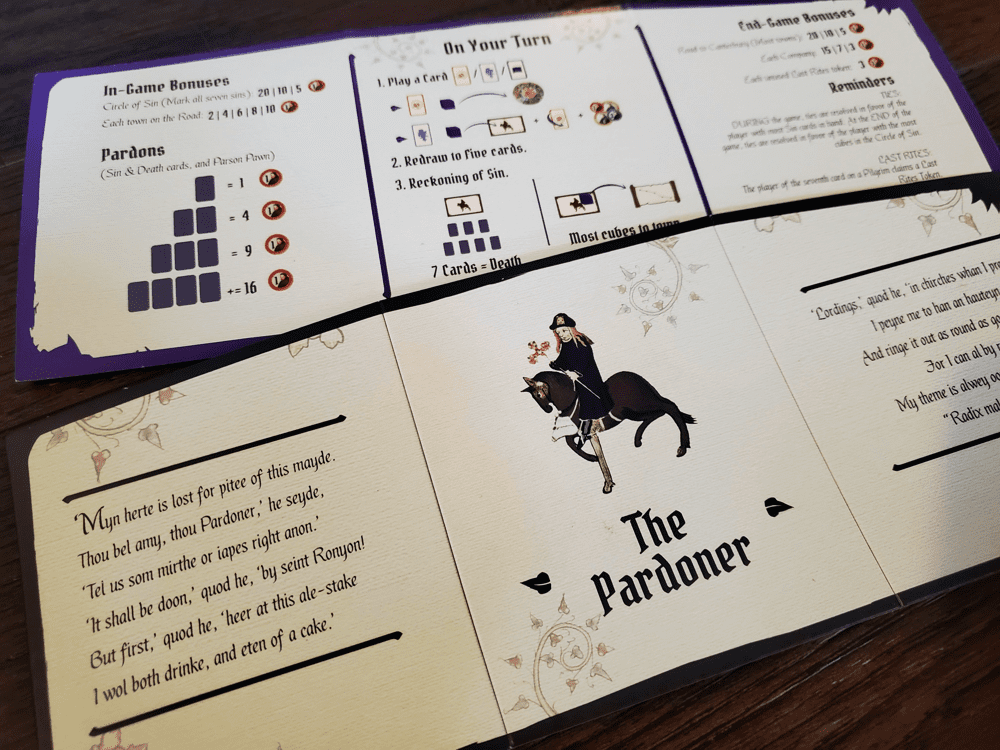

The component I simply must celebrate, though, is the player shield. Because coins and cubes are kept in the dark until the end of the game, a tri-fold shield offers shelter. I can’t tell if it’s simply the fold or if there are really magnets in there, but these things pop back out flat in the most satisfying way. Honestly, they remind me of snap bracelets. Every time the game is out I just sit there springing them back and forth. The inside is a highly functional player aid, making the teach easier and the in-game questions minimal.

With an expressly limited player count of either two or three, The Road to Canterbury makes no boasts to be more than what it is. The truth is, both counts work phenomenally well and I’m not sure I’d ever want to add a fourth player. The Pardons are more spread out with three players, and often for fewer cards due to the pressure imposed by potentially waiting an extra turn to capitalize. Overall, though, the experiences are largely the same from the clock to the scoreboard.

I have been so pleasantly surprised by the battle of wits inside. If you are intrigued by the satirical subject matter, you might find a winner with The Road to Canterbury. If you spy a copy and you enjoy area control as a mechanism, I would highly recommend taking advantage of the opportunity. If you miss the boat, though, don’t sweat it. I’ll pardon you this time, for a price.

Add Comment