Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

My Vital Lacerda game nights have been on the upswing.

After uneven experiences with games like Weather Machine and Escape Plan—the latter of which I liked a bit more than most people in my network—I thought Inventions: Evolution of Ideas was strong. Now, mind you, it is a hell of a game to teach, particularly the tile-laying mini-game positioned at the center of each player’s personal board. But the central puzzle and the creativity required to find all the ways to take the actions needed to get everything done…man, I thought Inventions was a blast.

Speakeasy, Lacerda’s most recent deluxe edition title from Eagle-Gryphon Games, was even better, in part because it felt like a Lacerda throwback. Elegant in some ways, and highly inventive in others, the main conceit with Speakeasy (besides its ridiculously gorgeous production) was the integration of its theme into the gameplay. For the first time since Kanban EV, it felt like Lacerda was back to delivering bangers that successfully married theme to interesting gameplay.

The Great Library (which launched its crowdfunding campaign on November 20th) is the next big box game from Lacerda and it’s quite a lot. When I showed this to groups in the weeks leading up to the campaign, the first question was always the same: “what’s the weight?”

In terms of the teach, The Great Library is going to feel like Inventions to many players: it’s a long teach, easily 30-40 minutes or more, and trying to explain all the game’s actions comes with a twist that we’ll get to later in this review. In terms of turn-to-turn dynamics for each player, The Great Library is pretty snappy. So here’s what I will say about the weight now: The Great Library is lighter than On Mars, Inventions and Lisboa, but heavier than Escape Plan, Vinhos: Deluxe Edition, and The Gallerist.

After four plays of The Great Library (two plays with two players and two plays at four players), I have some thoughts.

Welcome to the Mouseion

The Great Library is a tricky game to categorize, so let’s go with this: it’s a worker placement, pattern matching, tile-laying, pick-up-and-deliver game for 1-4 players that plays in about 45 minutes per player. You’re in Egypt in the third century BC and players take on the role of librarians tasked with delivering the manuscripts, Great Works, and assorted crafts to the Great Library in Alexandria, a part of a library complex known as the Mouseion.

That means the race is on to become the greatest librarian in all the lands! To succeed, players will race to score the most points by training a mix of young, middle-aged, and elderly scribes (yes, seniors are prominently on display in this game) at a local school, before sending them to a Scriptorium to translate manuscripts and fulfill orders sent by the King of Egypt.

Based on the description above, one would think that placing manuscripts in the Great Library would be the heart of the game. As it turns out, that’s not exactly true. Certainly, the main puzzle in this game is tied to placing items in the Library, represented here by a large grid in the central area of the board. By using a series of event markers known as Head Librarian tiles, Lacerda has designed the game to require players to make a series of adjacency matches in order for delivered tiles to score.

But a sizable portion of The Great Library is actually tied to a somewhat different game altogether. This shift was so surprising that when I first read a draft of the game’s rulebook, I actually started over because I was surprised to find myself reading a section about an action titled “Navigation.”

“Is this a shipping game?” I said to absolutely no one, out loud (!!), when I was sitting on a plane returning from SPIEL Essen 2025. Here is the first surprise about The Great Library: this library game seems to prominently feature…the management of a fleet of up to six individual ships (a fleet which is represented physically by a single token on the main board), with four ships that can carry resources like silver and papyrus while the other two ships can carry craft goods and translation stones.

The surprises continue. The main spendable resource in The Great Library is time, tracked in the middle of each player’s personal board. Everything in the game costs a measure of time, and finding the best ways to efficiently spend time is the puzzle that becomes a fun way to push through a round.

Further, The Great Library uses a mechanic I first saw in one of my favorite “Dusty Euros”, Caylus—as players pass to end their participation in a round, other players can continue taking actions in that same round for an increased action cost. In The Great Library, players can keep going within the same round after others pass, but they have to give units of time to anyone else who has already passed to keep rolling. (In a four-player game, that proved to be a very powerful motivator to pass; do I really want to spend three units of time just to take one more action?)

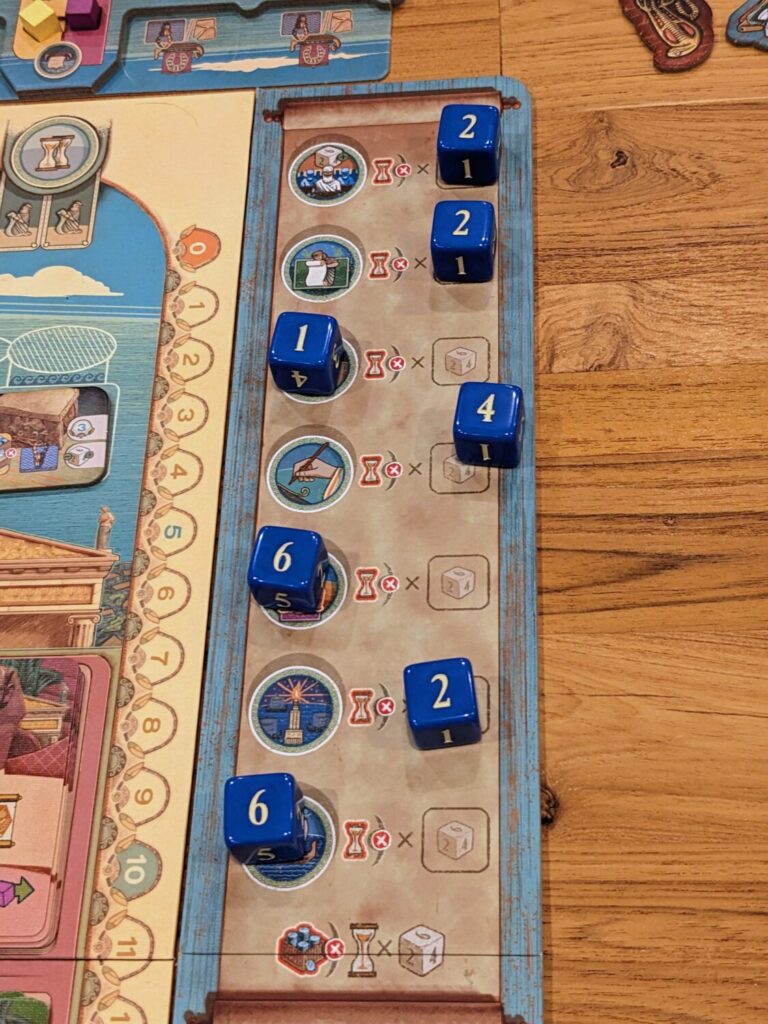

Another surprise? Dice. Just the presence of dice in a Lacerda game (a first) will throw some players off, but as it turned out, those fears were unwarranted. Dice are used in the right ways for a strategy game here, particularly as a predictable option for one way to take actions, something that can be mitigated by upgrades and certain game effects.

So, let’s pause to give Lacerda some credit here—at this stage in his career, he could absolutely coast and just give us another rehash of his most successful designs. But he takes some risks with The Great Library. Sure, there are still Executive actions, his phrase for bonus actions that can be done before, during, or after a player’s main action in his other titles. But in The Great Library, you can only take two types of Executive actions—and only before taking a main action—plus you won’t take one of the Executive actions for a good portion of each game.

There are 24 pages of rules and dozens of ways for me to waste time trying to explain every action in the game, so please visit the campaign’s landing page to find a link to the current draft of the rules. What I’ll try to do for the rest of this article is help you make a buying decision—is The Great Library a game only for Lacerda superfans, or is it a title that others can get behind?

When in Doubt, Navigation

The toughest part of the teach for The Great Library is helping players understand the five ways to take actions, as well as the seven locations where most of the game’s action takes place. In this way, those who are preparing to buy The Great Library and teach it to their gaming groups should buckle up: this is a two-part teach that proves to be a bear when showing off the game.

The Great Library features five ways to take actions: by placing a worker (workers here are known as Scholars, both Local and Invited), by using one-use-per-game action tiles known as Location tiles, taking a Time action (which uses the dice mentioned above), fulfilling an order card known as a “King’s Request” that pushes items into the Library on the main board, or the “Read” action, which is simply passing.

I taught the game from scratch three times for my four plays (the fourth play was with a friend who joined one of the four-player games), and while I had my routine down pat, I was surprised that teaching this game felt so challenging. In part, that’s because you have to tell every player what is possible on their turn, but you can’t do that until you first describe how they can do that, and the ways actions trigger felt a little different from other games because of those choices.

The biggest challenge was reinforcing the fact that Invited Scholars can be used to take both Executive actions AND main actions. Players begin the game with two workers, known as Local Scholars, and they are used during a Planning phase before each round to select two actions each player wants to take during a round. The more important portion of this Planning phase is using these Local Scholar placements to generate time income, another mechanic in the game I really love.

But players usually only remembered that they could use Invited Scholars (which are unlocked when visiting the Garden location, which we’ll cover in a bit) for Executive actions. Often, players complained they couldn’t find ways to take any more actions in a round once they had triggered their Local Scholar actions—when, in fact, they could have used their previously unlocked Invited Scholars to continue taking actions, assuming they had the time to do so.

The Time main action was the action players seemed to warm up to the most as games moved from round to round. At the start of each round, 4-7 standard D6 dice are rolled and placed across a variety of spaces aligned with the game’s seven main actions. These dice offer another way for players to trigger location actions, but they also offer a chance for players to spend one silver to buy time from the Time board. The pip values of dice can be mitigated by a bonus on each player’s Workshop (personal player board) or any time Craft tiles are currently on a player’s Workshop.

Everyone loved this mechanic. Even when the die results looked obvious—ahh, there’s a 6 on one of the spaces, so I’ll use that to buy six time when my turn comes around! However, players might use their mitigation bonus to flip a 6 to a 1 and use that same die to take an action instead, for a cost of one time plus the normal cost of the associated action. Sometimes, a desperate player with extra silver might buy a 3-pip die for time, or use a 4-pip die to take an action.

In one case, a player noticed that an opponent was out of other action options to take a Scriptorium action, so he just burned the die to buy it for time and hose their opponent. I love the flexibility of what that Time action offers.

So, you’ve got to teach players how to take a turn. Then, you’ve got to teach them what happens at seven different locations on the board.

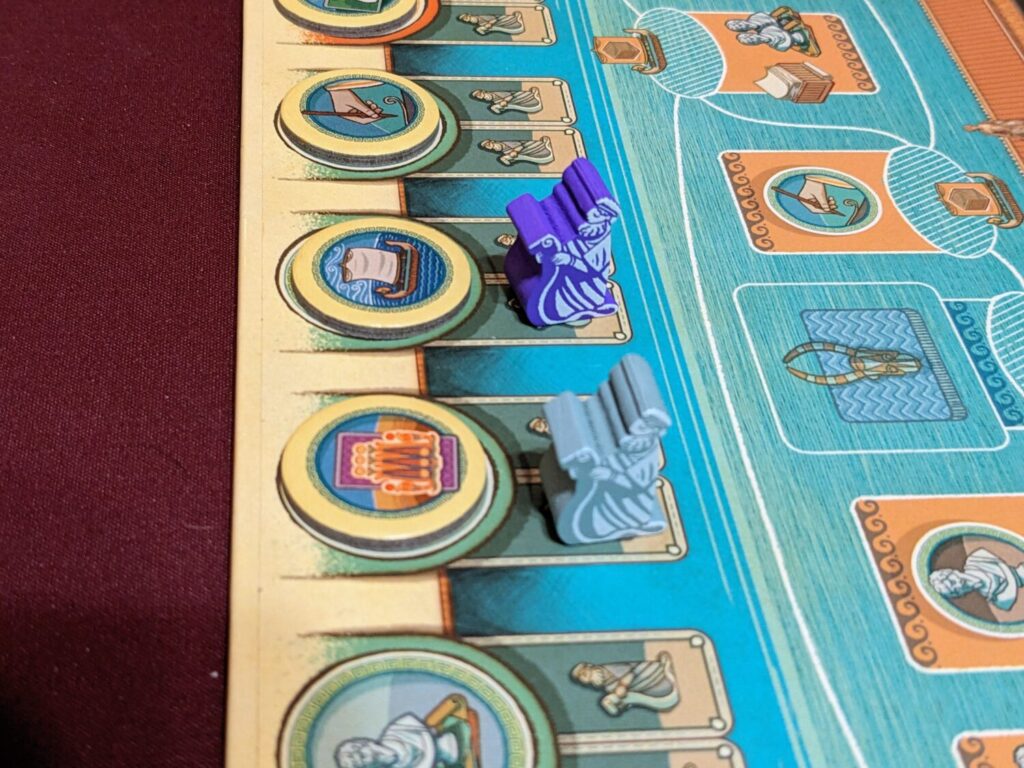

I am fortunate to play heavier-weight games with a lot of very smart people. And after just a few turns in each of my four plays, all those players discovered the same thing: the best location on the board, by a country mile, is the Navigation action.

It’s the best location because it is the only location that has all six of the other location actions on its track along the top third of the main board. Navigation has the best tiles to place in the Library: Craft tiles, which can be played as a wild to take the place of anything used to fulfill a King’s Request card. Navigation has bonus spaces to get resources and research tokens. It has the Translation Stone tokens needed to acquire Great Works through a separate action, and it has ways to deliver resources for points whenever a player’s Fleet token returns to the Alexandria space and is tied to an Executive action.

In other words, the Navigation location is the most flexible location in the game. Boxed out of the spaces where you can take a Garden action to acquire more Invited Scholars? All good, you could just drive your Fleet token to the Navigation space that features the Garden bonus. Hoping to get more King’s Request cards, but can’t find a way to get a Local Scholar or Time action for the Palace location? You’ll be fine…just take the Navigation action, move your Fleet token to the Palace bonus action, and while you’re there, you can fill any unlocked Merchant Fleet spaces on your Workshop with more crate goods.

We quickly found that having a Location tile with the Navigation action ensures flexibility when all else failed. At the start of a round, if the Navigation action had a low-value die attached to it on the Time board, a player would take the action there. The rulebook hints that getting Craft tiles early is vital (not Vital), so everyone has to race to grab those tiles. The time cost to take the Navigation actions is pretty low, and two different bonuses and a host of other game effects make it pretty easy to move the Fleet token from space to space.

During each Planning phase, players began racing to snag one of the spots under the Navigation action every Generation. This was especially true when the Navigation token was near the back of the Generations track in a spot where it could both generate a lot of time income for a player and offer them at least one crack at the game’s best action.

Let’s Talk About Fun

The Great Library’s key moments of fun appeared in three areas: taking Navigation actions (the game’s main way to form satisfying combos), unlocking Invited Scholars to take Executive and/or main actions, and getting items into the Great Library area of the board to score.

Three types of items can be placed into empty spaces of the Library: manuscripts, Crafts, and Great Works. Acquiring manuscripts is a two-step process, involving training scribes at the School location then, later, moving scribes to the Scriptorium to translate manuscripts, scoring the owner points and moving those manuscripts onto shelf spaces in a player’s Workshop. These manuscripts can then be used to fulfill King’s Request cards with requirements in three flavors: Arts, Laws, and Medicine.

That can lead to a bit of a grind, so players will find ways to use Craft tiles (remember, they serve as wilds) in combination with manuscripts to fulfill King’s Requests and get their items into the Great Library. Placing tiles there is a fun puzzle; The Great Library has an event tile next to the Library each generation that changes the rules for what tiles will score based on their orthogonal adjacency to previously-placed tiles.

In some rounds, that means that Arts tiles only score if they are next to a Craft tile. Or, maybe a Medicine tile will score if it is next to either an Arts or a Laws tile. Players can always choose to place a tile anywhere in the grid, meaning that it might not score at all, and that tile could instead be used only to get a bonus covered by the tile.

Placed tiles can trigger bonuses for the active player as well as their opponents, based on who owns the tiles that triggered the active player’s scoring. These Library tokens are the other way to take Executive actions to start a turn, and while these were often minor bonuses—two time here, a papyrus there—a couple of the Library bonuses on a player’s Workshop are pretty juicy, none more so than the one that lets a player fly their Fleet token all the way back to Alexandria for free.

So, hangin’ out in the Library is a good time. The result of pushing things into the Library: the ability to attract Invited Scholars by taking the Garden action, a Location that can’t initially be used thanks to the requirements of the cards in the display there. When players begin to visit the Garden, The Great Library really opens up to reveal itself as a game that shows off Lacerda’s creativity.

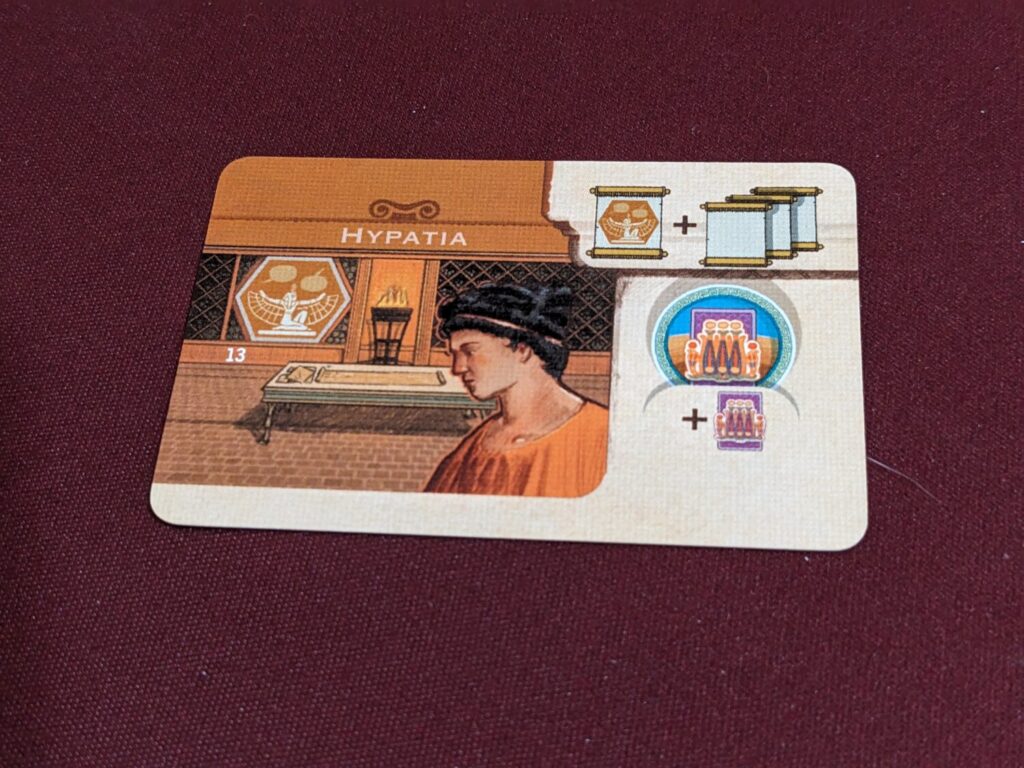

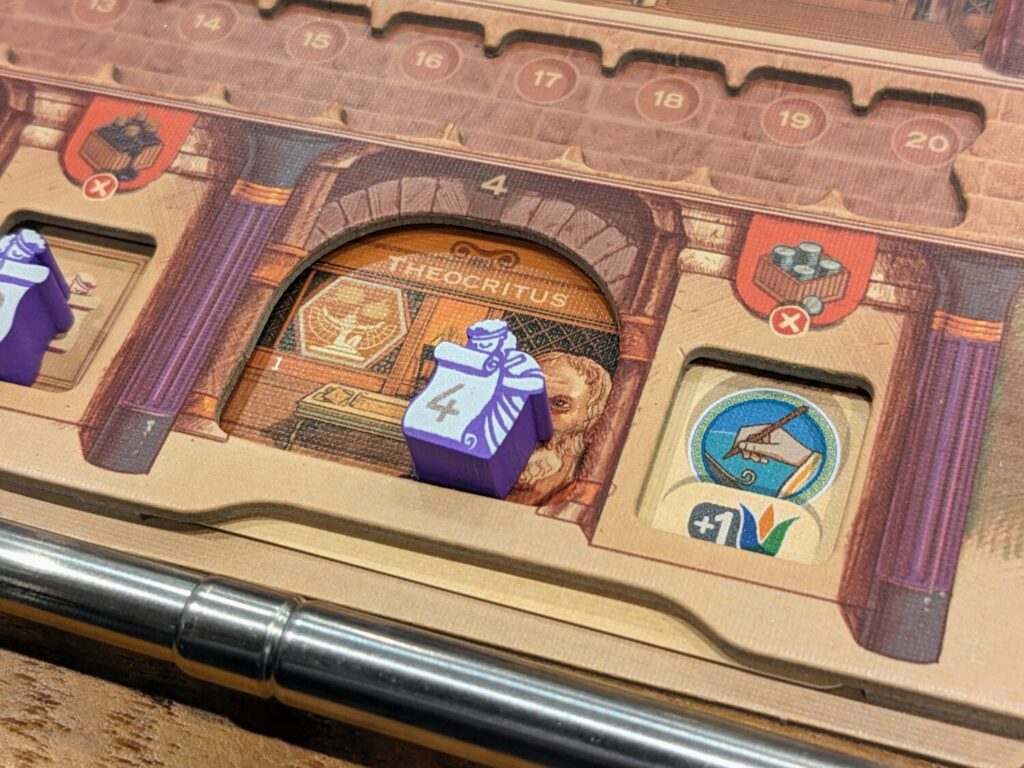

Like any efficiency puzzle, being able to take more actions is a good thing, so it’s clear that players will need to eventually begin getting Invited Scholars from the Garden. I love the way this mechanic works, by spending time to unlock one of the four workers at the bottom of a player’s Workshop. Each Invited Scholar is a named character with a small card that gets slid into the bottom of a player’s mat (I see you, Speakeasy-adjacent player boards!!), making that Invited Scholar available for future turns.

After paying a one-time-per-generation fee, players can then use their Invited Scholar to take main actions—just like a Local Scholar—but they can also slide an Invited Scholar into one of the four Location areas where they will be taking an action on that same turn to reduce the time cost, a discount based on the value of the Invited Scholar (between 1-4 units of time).

Further, unlocked Invited Scholars can be moved around between Executive action spots as long as they are on the board. Finding daisy chains to keep those guys in an Executive action space was a blast; using Invited Scholars to eventually take a main action near the end of a round was another fun challenge. In successive generations, Invited Scholars can be unlocked again to do your bidding as needed.

The Invited Scholars were one of the best discoveries during my plays. In my first game, I didn’t even try to unlock one during the game’s first generation, since I was so sure I wouldn’t be able to take advantage of that. Big mistake. By my fourth play, I was placing a Local Scholar on the Garden action during the Planning phase. Each Invited Scholar also has its own action that can be used if you don’t want to use that token on the main board.

I found myself using Invited Scholars to reduce costs at the School, then moving them to the Scriptorium to save time on manuscript translation, then later using its card action back at my Workshop to do something else useful.

Creative players are going to love the Invited Scholar mechanic quite a bit.

What Didn’t Bring Joy?

My main issue with The Great Library is that it features one…no, two too many Location spaces, and one mechanic that is strictly less valuable/meaningful than everything else in the game.

As it is, players began to ignore certain parts of the design as they moved through each game, even during their first plays (and markedly so during their second play, from the evidence I found watching one person attack the system a second time).

The Navigation action is the best Location in the game. Leaning hard into Navigation actions also led to my highest score across my plays. While I would rather fulfill KIng’s Request cards by using Craft tiles, I was often forced to do School-Scriptorium actions to get specific tile types, mainly to acquire new Invited Scholars at the Garden.

So, you are going to spend most of your time doing the Navigation, Garden, School, and Scribe actions, plus the Harbor action, the only way to open spaces in your Fleet area of the Workshop to carry more stuff when taking the Navigation action to grab additional resources. One player, after finishing our first four-player game, spoke openly about how he would turn his entire game into a “Navigation-Harbor” strategy in a second play, because doing that would be all he would need to take the game’s Location actions anyway.

I get it. But that also meant players mostly didn’t bother with the Academy action to acquire Great Works.

Even the rulebook acknowledges that getting Great Works is a “slower” way to gain rewards that can be found elsewhere. But in a higher player count game, I found that the game didn’t offer many generations…only three, in both cases. That means to get a Great Work, you have to do all the following things, and pretty quickly:

- Use Navigation actions to move your Fleet token to a space with a Translation Stone, loading it onto a Royal Fleet space on your Workshop.

- Return your fleet to Alexandria, to move the Translation Stone into your available supply.

- Take Academy actions to move your markers up one of the three tracks to get in position to spend a matching Translation Stone to take a Great Work, assuming other players have not beaten you to the punch on the same track with a Translation Stone of their own.

- Because of a rule placing limits on the number of spaces a player can move on any Academy track during their turn, it takes at least two turns to move into position to get the level one Great Work from a matching track, as well as time and research tokens to get the token.

Everyone who joined me for plays questioned the strategy behind going after a Great Work. It takes a lot of turns and resources to get in position to even acquire a Great Work, assuming no one else is racing you to get the same one you’re chasing. Because of that rule slowing the pace at which a player can boost up a track, it can take as many as four turns to get to the level three Great Work space on a track.

The game clock is tied to an event system, and at some point, one of the Great Works burns in a fire that removes it from play, with a second also happening to trigger the end of the game. If you don’t check that when chasing a tile, you might be chasing something that will be removed by a game event!

Further, the bonuses for the second- and third-level Great Works are really weak; they are the same bonuses offered by some game effects as well as the entry-level Invited Scholar cards. (The reward for the first-level Great Works is surprisingly strong, however: players will be able to move their Fleet token up to five spaces for just one unit of time, instead of the normal cost of moving 1-2 spaces for one unit of time. If you are really going to chase a Great Work, chase the level one tiles!)

One player in each of my four-player games—me, in my first play, and a different player in my second game—tried an Academy/Great Works strategy, to disastrous results. I just don’t think that process is interesting and it certainly didn’t pay off in terms of points.

That meant that the Academy was mostly ignored in my plays, as was the Palace action. Players need King’s Request cards in order to place items in the Library, so eventually, players will have to go to the Palace. But using it as a main Location action was generally a miss. One of the Library token Executive action bonuses grants players a card without having to visit, which has become the first bonus I unlock during setup so that I don’t have to waste time to get a new card. Using bonus actions to get cards by taking the Palace location action during Navigation turns was another way I got around visiting the Palace.

I’m not going to pretend I am a game designer, and other players might find some of these locations to be more fruitful in their plays. But if The Great Library only had five locations, it would still bring me the same amount of joy. If order fulfillment cards could be picked up anytime a player fulfilled an order—I finished an order, now I get a new contract for free on the same turn, for example—I think that would speed play and remove a rule for rule’s sake.

One last thing that one person is just going to have to accept: someone, probably the person who taught the game, is going to have to police players around the expenditure of time. Much like other games where someone has to referee the use of money—”hey, Johnny, you spent the $4 for that action, right?”—someone is going to have to police time here. Call them the Timecop (hey hey, Van Damme!), then make sure they closely track players to ensure they are spending time and goods to take each action. Missing this can badly throw off your game; in my first play, we had a player “forget” to pay nine units of time when he took a Scriptorium action, which gave him plenty of time to take other actions in the same round.

Where Does That Leave Us?

Across my four plays, I showed The Great Library to seven other players—six from my network (in the four-player games), and one complete stranger, a player who met me for a two-player game at a local board game cafe. I like to show Lacerda games to superfans, players on the fence, and people who have begun to tire of the designer’s heavier work. This helps me round out opinions quite nicely.

Those opinions varied widely. One of the superfans, a person who loves The Gallerist, Kanban EV, and Vinhos: Deluxe Edition, loved The Great Library. One of the players who fell out of love with Lacerda designs after Weather Machine—a game I also did not enjoy—also really enjoyed The Great Library and said it was a game that might get him to back the game when its crowdfunding campaign begins.

A different player—someone who likes complex titles but is indifferent regarding Lacerda—really hated her single play, citing a “rules bloat” that reminded her of heavier games that ran afoul of the term “complexity for complexity’s sake”, which reminded me of my thoughts on Weather Machine’s major issue. Another player was happy with the central puzzle on display in The Great Library, but wondered if he would really want to sit down for a second play when there are so many other great Lacerda games in his collection.

All of this means that The Great Library proved divisive. Inventions: Evolution of Ideas and Speakeasy both experienced smooth sailing with other guests who joined me at the table, including many of the same people who joined me for The Great Library.

That helped me form my own opinions. Across all four plays, I really enjoyed the central puzzle of getting items into the main library spaces at the center of the board, even while playing “chicken” with other players to time the placement of tiles into the Library. By my second play, I loved getting Invited Scholars into the mix and did a much better job of shopping for the right Scholars to ensure I had Location variety on my player board, especially useful in cases where I needed the right actions but went later in turn order.

Also, unlike Weather Machine and Inventions, I am thrilled to share that turn order actually matters in The Great Library. Playing last allows a player to enter the Planning phase first. This helps lock in the actions a player wants and guarantee a large amount of time income, if desired. But going first when taking main actions can be huge, especially when trying to claim specific spots in the Library, grabbing an Invited Scholar that caught your eye during end-of-generation clean-up, or acquiring a fresh Time die for a specific Location action.

If you follow my content, you already know that I much prefer games at their maximum player count; in most cases, I’m all about the chaos. The Great Library ended up being a bit different with my four-player games versus the two-player ones. At two players, the games ran deeper; in my second two-player game, we played into the fifth generation, took a couple dozen actions, and got into the final third of the Invited Scholar cards. (This was the only time a player had four Invited Scholar cards and was able to buy a fifth to kick one of their first four off their player board.)

The nice thing about this? The game didn’t add much in the way of additional playing time, but I got to explore more of everything. In fact, my second two-player game wrapped in just under 90 minutes. For a game with so much going on, the two-player games felt a lot more epic and left both players feeling like they accomplished quite a bit. (I did not get to try the game’s solo mode; the prototype did not include solo rules nor components, but the retail version of The Great Library will have a solo mode.)

At four players, a number of things change. One thing that was immediately apparent: when one player mismanages their time, that affects everyone at the table. Someone who passes early forces all other players to spend extra time just to take actions, which turned one of my plays into an interesting affair—what if I don’t have enough time to even take the actions I booked during the Planning phase with my Local Scholars? When each player takes different spots with their Local Scholars in a four-player game’s Planning phase, the Generation clock moves a lot faster.

During setup, each player is given one private milestone tile, called a Pinax token…these are used to form patterns with Library items for additional end-game scoring. In a two-player game, these are much easier to work around to score their maximum value. In a four-player game, the Pinax tokens are much harder to complete when other players are seeding their items into the Library. One player from a four-player game noted that the Pinax tiles feel like bonuses you fall into, rather than plan for, with so many other players able to influence the board state.

The Great Library is “looser” than other Lacerdas. In Kanban EV, Speakeasy, and even Vinhos: Deluxe Edition, it feels like you never have quite enough of what you need to succeed…so you do what you can based on how well you planned in earlier rounds. The Great Library doesn’t have that level of tension. The King’s Request cards at the Palace always have viable options, with five face-up cards. Getting crate goods (silver, papyrus, and ink) is as simple as moving your Fleet token around the Navigation area. I was initially worried that time would be super tight, since it serves as the game’s version of money.

Nope. I began to see players with middling amounts of time simply passing, forcing other players to take much more expensive actions while also generating a small time drip for any players who previously passed. You can usually buy a Time die or two from that area of the board for a single silver. Using Invited Scholars the appropriate way is a massive timesaver, and bonuses later make certain actions a little cheaper. In a three- or four-player game, there are sometimes gaps in the Generation track that give some players a chance to get a massive time income boost at the start of a new round.

In this way, The Great Library is a bit like Galactic Cruise. The challenge comes from finding the most efficient way to win the race, not from a tension tied to scarcity. Even in prototype form, it is an exceptional production; Eagle-Gryphon still does “deluxe” better than any publisher in the business. The rulebook is solid, although in a strange twist, the player aid is a bit too short for a player to fully use it as a rules aid. (That Lacerda and EGG essentially invented the deluxified player aid now replicated by games like Galactic Cruise is an ironic twist, given the lack of one here.) Games of The Great Library, untethered to a specific number of rounds or turns, could grant a player 10 turns, 20 turns, maybe more.

In the final analysis, The Great Library is a pain to teach but it is quite breezy once it is in motion. While I wish the player aid detailed more of what can be done at each location, the reality is that most players who joined me for plays had the mechanics down by the midpoint of each game. Ian O’Toole is back in the mix and the icons mostly work to inform players of its language quickly. The player board design is great, the overall layout of the main board is good, with the only hiccup coming in the form of the harder-to-find Location spaces. The board is busy, so the worker placement spaces got a little lost. This was especially true when players needed to figure out where to place their Invited Scholars during Executive actions the first time around.

The Great Library is good. Its Navigation action is great. The puzzle is a fun challenge, and the playtime is reasonable for its weight. The Great Library doesn’t crack my top tier of Lacerda designs; Kanban EV, The Gallerist, Speakeasy, and Vinhos: Deluxe Edition hold a place in my heart that remains safe. The Great Library resides firmly in that next tier, with titles like Inventions: Evolution of Ideas, Lisboa, Escape Plan, and On Mars. (I still believe that On Mars is both Lacerda’s best design and the game that is the hardest strategy game to table in my entire collection. The rules load is a bear.)

I’m excited to explore The Great Library in more detail when the crowdfunding campaign fulfills next year!