“And in the end, of course, a true war story is never about war. It’s about sunlight. It’s about the special way that dawn spreads out on a river when you know you must cross the river and march into the mountains and do things you are afraid to do. It’s about love and memory. It’s about sorrow. It’s about sisters who never write back and people who never listen.”

-Tim O’Brien, The Things They Carried

I’ve yet to come across a narrative game that features “CHOICES™” that hasn’t been an insult to the intelligence of its players. That said, my bar for these sorts of experiences is very low.

And yet, Purple Haze manages to limbo underneath said bar to perform the exploitation cash grab hat trick: infantile Hollywood Vietnam tropes, wishful thinking armchair squad commandeering, and a barely serviceable choose-your-own adventure framework.

The Back of My Mind Every Time I Play A Wargame

One of the reasons I seek out exceptional or odd wargames is because I am interested in historiography–the how of our historical memory. I think this is a commonly shared interest among people who play this style of game. But there is always a question at the back of my mind whenever I engage with a game about a “real” conflict: what am I playing at?

At best, a solid game about history accurately models the material positions of the forces involved.

Games like Triumph and Tragedy attempt to model large scale political and economic forces that pushed countries into WW2, and how things like geography, matériel, economic productivity, supply, and command affected that conflict. When you’re modeling the grand scale of a conflict, you actually end up creating abstractions of various historical events that are more easily criticized and/or deemed to be accurate. Sillier but interesting games like Quartermaster General capture this as well.

You can also zoom in on the map a bit, in the way that the Southern US map for Age of Steam does, utilizing the rules of the game to show how the CSA’s monomaniacal obsession with a cotton economy translated into totally crap rail networks that couldn’t move things efficiently and ended up being a massive hindrance to their war effort.

Then there’s the real up close stuff, games I grew up playing with my dad—hex and chit wargames like Afrika Korps, Midway, Chancellorsville, and other Avalon Hill joints. These games are deeply obsessed with individual battles, the experience and equipment of troops, and the minutiae of terrain. I have nostalgia for these games, but ultimately, I’m not interested in battle simulations. I couldn’t care less about why a particular general won a particular battle, at least not beyond a basic broad strokes understanding of what they did. It’s not evil or anything to be interested in or like playing this sort of thing. I mostly just find it boring.

However, all games about history (and many that aren’t) have politics and contain propaganda, whether you like it or not. This is doubly the case for games that pride themselves on their narrative elements. When I ask what are we playing at, I am seeking an answer to the problem of the game. Games are not arguments, stories, or any other high-minded descriptor that various folks throw around. They are problems, and players, through play, come to an agreement about what the most correct solution to those problems are. That’s the magic.

Game series like CIA-guy Volko Runke’s COIN series ask “how do we put down an insurgency?” Many eurogames ask “How do we make the most points the most efficiently?” Critique’s purpose is to ask if these problems are worth solving, if they’re presented accurately (here’s looking at you COIN) or if they’re even interesting problems.

Purple Haze’s big problem question is “can I roll dice good?” It tries to present a compelling role-playing literary experience along with the dice rolling, but as far as I’m concerned, it completely fails at both.

Exploitation with a capital “E”

I’ve spent most of my life writing and reading. I describe myself as a dropout PhD in literature, which makes me sound edgy. The cool thing about having no institutional affiliation is that you can say anything you want about what you think good writing is. This is a rough paraphrase of Steven Erikson, but I believe that it is both irresponsible and inhumane to exploit reality for the sake of my little fictions. The lives and narratives of others are not fodder for my mid-tier storytelling. If you have anything in your life, it’s the story of it. In my holier-than-thou manifesto, the goal of fiction is to raise the subjects of your writing beyond the grotesque brutishness of reality. To even attempt to do anything else is criminal sophistry.

I’ve gotten 800 words in and haven’t even talked about the game much yet—always a good sign. Ok, here goes: from what I just described above, if I’m being generous, I would characterize the narrative work of Purple Haze as hack. Here’s a little sample from the intro:

“You’re exhausted before you’re half-way to anywhere. And then VC’s on top of you. One second you’re walking, restless, but alert to the slightest fart in the grass. The next, grenades are flying from fuck-knows-where and landing everywhere. Half your squad is dead. The enemy machine gun makes light work of body, muscle and bone, and your face is pushed so hard in the mud it’s like you’re digging your own grave.”

Or when you find a wrecked helicopter:

“One of your Marines pops vomit right on his boots. Others search the wreck. They try not to look at the human meat all around them.”

Or when you come across an old woman in the jungle:

“The old woman doesn’t stop mumbling even as you leave her alone. ‘If I get that batshit crazy and old, just fuckin take me out and shoot me,” says one of your veteran Marines. ‘What are you talking about?’ Says a Marine humping the radio. ‘ You’ve been that batshit crazy and old since I was in first grade.’ The veteran Marine flips the bird. ‘Yeah, yeah, that’s funny, kid, I’m just a year older than you.’”

How about when you’re escorting bulldozers through the jungle?

“The bulldozer belches petrol smoke into the air as three tons of stars-and-stripes rip through the veg. You and your squad stalk behind it, eyes peeled for Charlie. There’s something comforting about not having to eat mud another day.”

I wrote one of those. Can you guess which one?

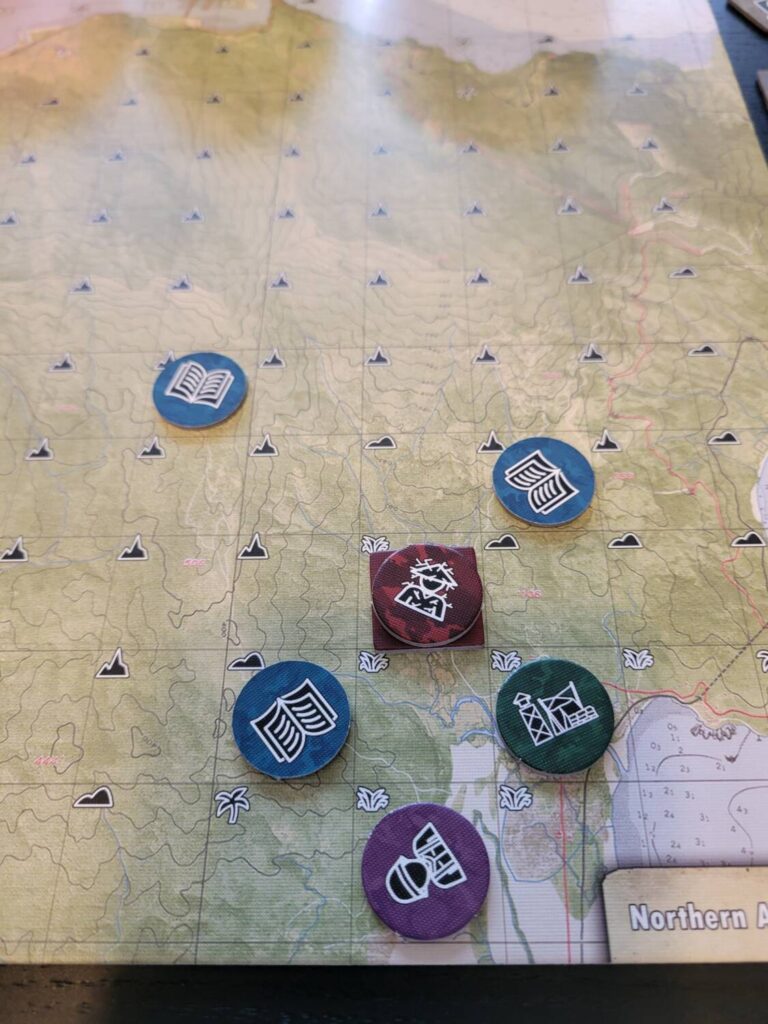

The game follows a pretty simple rubric. You’re a fictional squad leader during the Vietnam War in the late 1960s. You have a pawn that you move around a grid to visit various tokens, which upon revealing, you consult a book full of prompts. There are some other mechanisms to contend with, where you need to balance the path you’re taking through the grid with a stamina statistic and a game timer, but ultimately, each of the game’s 9 scenarios is something to the effect of “go collect the tokens and do your reading, soldier.”

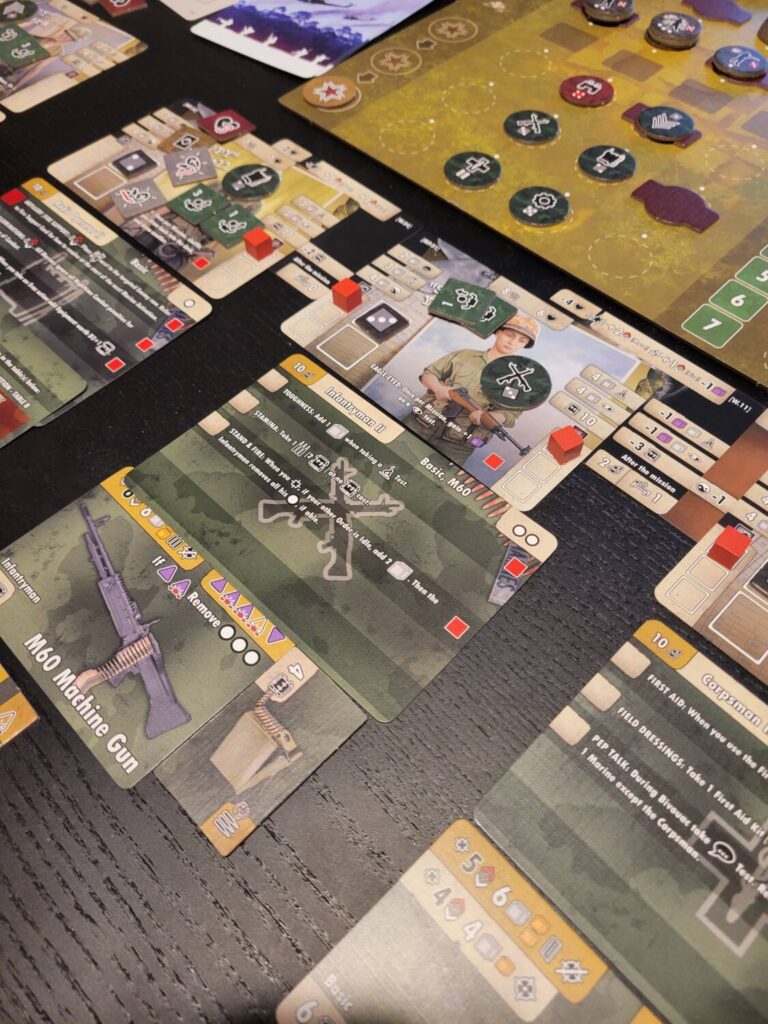

You have a squad of 6 guys (I did not play this multiplayer, and from what I can tell, there’s not much to be gained through that experience, one player makes most of the decisions and then gets to make some basic combat rolls—more on this in a second) and they have some statistics, most importantly a brain (representing mental resilience or something) and a heart (which is HP, each time you exceed the total you take a wound and your other statistics suffer and the soldier might die).

When you’re confronted with the baby-brained moral choices of the text, like “burn a village or don’t” you typically need to roll some dice and determine if your scout noticed that one of the huts you are about to burn has an AK-47 in it, thereby justifying said burning.

Combat is where you get to do the most thinking, and it’s pretty sparse. It reminds me a little bit of Too Many Bones, where you arrange different types of units on a grid, try to use your best skills at the right time, and roll lots and lots of dice to determine if your M16 barrage hit the enemy enough. Then they shoot back. The dice system is mechanically the most novel part, utilizing a system of matching and critical hits, where you need to collect enough purple focus dice to raise the odds of getting matches with piles of white dice that you roll.

Empty Headed History

If the way I’m talking about this feels mean or dismissive, it’s because it is. This is a game that, in order to complete, you must make your way through all 9 scenarios and endure what can be at best called writing that would be rejected from Adventure magazine. It’s an amalgam of the worst tropes from the worst war movies, all presented with a tough guy attitude you’d find in back issues of The ‘Nam. It’s made me feel insane and alone in the world that reviewers that I respect like Dan Thurot have showered it with praise. The writing was so consistently irritatingly trite that I was tempted to write this review in the style of this Dan Brown review (from the telegraph, but link avoids the paywall).

Things like this are the truest expression of O’Brien’s lament, that true war stories are about “people who never listen.” This is a story written by one of those people.

In spite of a little thing at the beginning of the rules where they said “oh no Vietnam was also horrible for the Vietnamese people,” there is little reflection or thoughtfulness in this text beyond a ripoff of the end sequence of Apocalypse Now. The Vietnam war and its prelude (check out Operation Vulture sometime) and aftermath were plainly and simply, a neocolonialist effort that destroyed enormous amounts of lives, hollowed out a generation of people to the point of no return, and helped create a military industrial complex that continues to scream into our present.

One of the opportunities that creating a game about recent history offers is immediate temporality. You get to speak to the present about things that might be forgotten while you still have a chance. Once enough time passes, wars and conflicts become abstract things, toys on a board from antiquity. I worked on crisis lines for more than a decade, and in that time, I worked for an organization that took overflow from the VA. I talked to numerous aged Vietnam veterans—I do not exaggerate—the violence, cruelty, and stupidity of this war erased a generation of young men. Their lives, and a near endless amount of invisible dead in Vietnam and Cambodia, are cheapened by work like this.

Good military fiction, whether it’s fantasy, sci-fi, or locked into a reality similar like our own, ends up being vehemently anti-war. Purple Haze is the Vietnam war delivered by Major Payne. It is an enormous failure of imagination and far and away the worst game I’ve spent far too much time with this year. I have no alternative recommendations for games about this conflict, because most of them are bankrupt in other ways. But hey, if you like reading about characters that are described as being “all dick and ribs,” maybe this is the game for you.

I agree with you that there’s ‘nothing to be gained by multiplayer’; but disagree with nearly everything else.

I have only done three missions but on the strength of my enjoyment I’ve pre-ordered some of the expansions.

However, your review was an enjoyable read and well-written and you’ve found another reader for your blog (previously unknown to me).

Games are games and as such don’t typically do heavy philosophical lifting. They are the Disney rides of history meant to be fun and entertaining rather than engaging us in looking glass moments of retrospective thought on the meaning of life and war and colonialism….

I’ve played through this one once and the game system handles firefights in a fresh and engaging way – yes the story / mission narrative is trope city but again – it’s a game.

The components are well made and high quality.

I don’t regret the purchase and enjoyed the game play for what it was. No, it’s not a documentary on the causes and consequences of the war but I doubt that is what it was intended to be either.

Good lord, what a pretentious article. The lead in was so unbearable I had to skip several paragraphs to the actual review to keep from straining my eyes from excessive rolling.

Its ultimately my fault for not stopping after, “I describe myself as a dropout PhD in literature…”. The author may give the game a half star (a ridiculous rating for anything except Candyland), but that would be too generous for this nonsense.

This game has an 8.2 out of 10 rating average on Board Game Geek with over 200 ratings. It is interesting the reviewer is so far in the other direction. Clearly it is a hit for the vast majority of folks.

Haven’t played the game, and definitely will not (to be fair the game was not up my ally in any case) but I do appreciate your perspective.

Vietnam sure is… a choice.