Power Grid, designed by Friedemann Friese and released in 2004, is a game that mixes economics, auctions, network building, and resource management. Over a series of rounds, you bid on power plants, place plants across your expanding series of connected cities, buy the materials needed to power your plants, and then earn money for providing power to those cities. The player who can power the greatest number of cities at the end of the game is the winner.

Sounds pretty easy, right? And yet, consider Power Grid remains on many people’s list of favorite games over 20 years after it hit the market. If you’ve played the game, you know why that’s the case; if you haven’t, we have a treat for you. We’ll start with how to play the game, and then Tom, Abram, and Andy will discuss why Power Grid is such a great game.

Diode, Cathode, Electrode

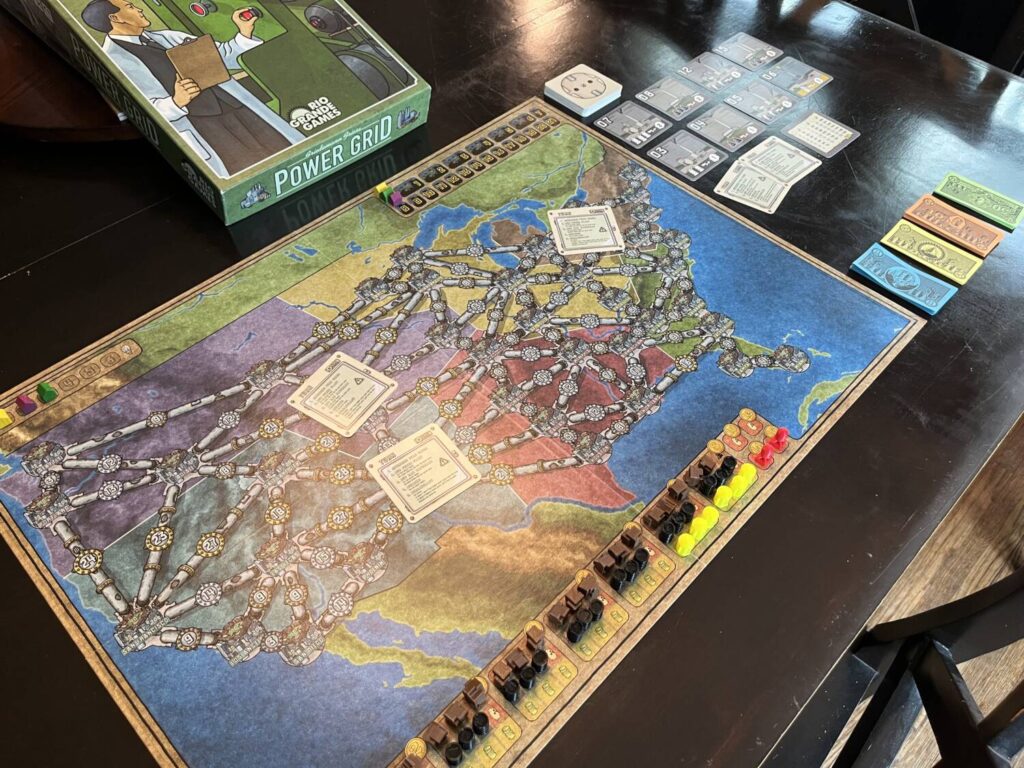

Inside the box you’ll find a double-sided game board, with a map of the USA on one side and Germany on the other. Your first decision in the game is to choose which side you’ll use to play.

Once decided, each player receives 22 buildings in their chosen color, a helpful card detailing the payouts for powering specific numbers of cities, and 50 Elektro, the currency of the game.

Each map is divided into six regions, each designated with its own color. You only play in connected areas equal to the number of players. (e.g., you play a three-player game with three areas, etc.) Choose the areas you’ll be playing with and, if you’re playing with fewer than six players, consider using the plants of an unused color to create a border separating the playable regions from the unplayable areas. It’s not necessary, but it can be helpful, especially for first-time players.

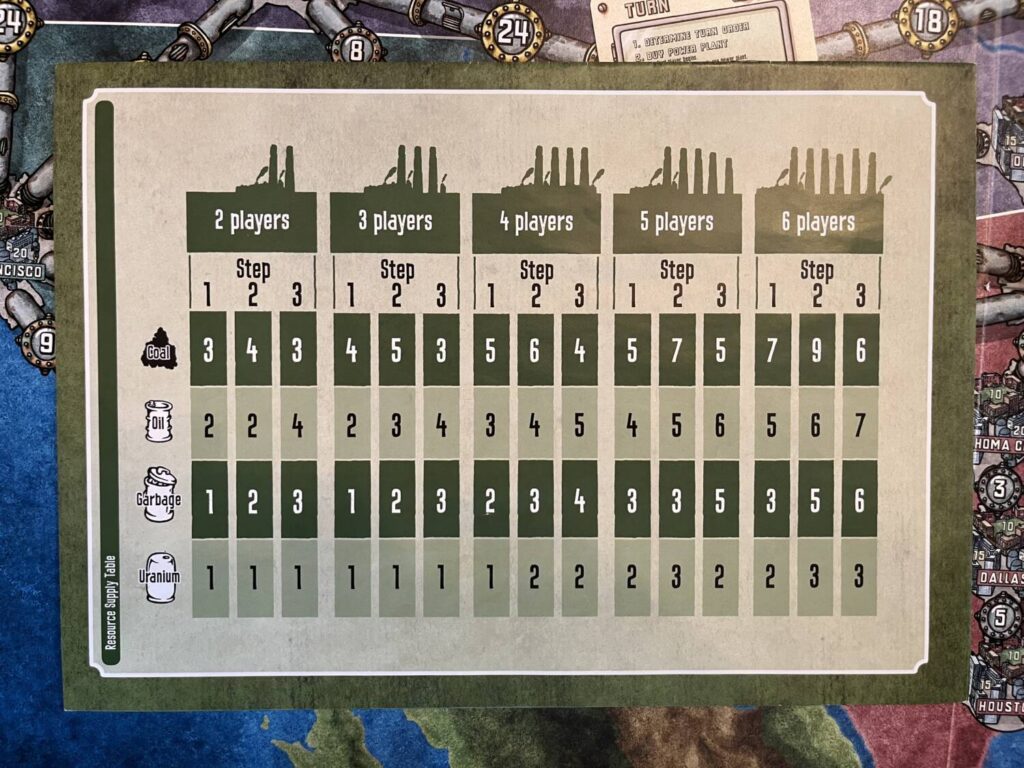

There is a chart in the rule book that you’ll reference throughout the game. It details how many of the game’s resources you put out for each round. These numbers depend upon the number of players and the phase of the game, so check the chart before setting out the initial offering of the four plant-powering resources—coal, oil, garbage, and nuclear—for your player count along the bottom of the board in the indicated areas.

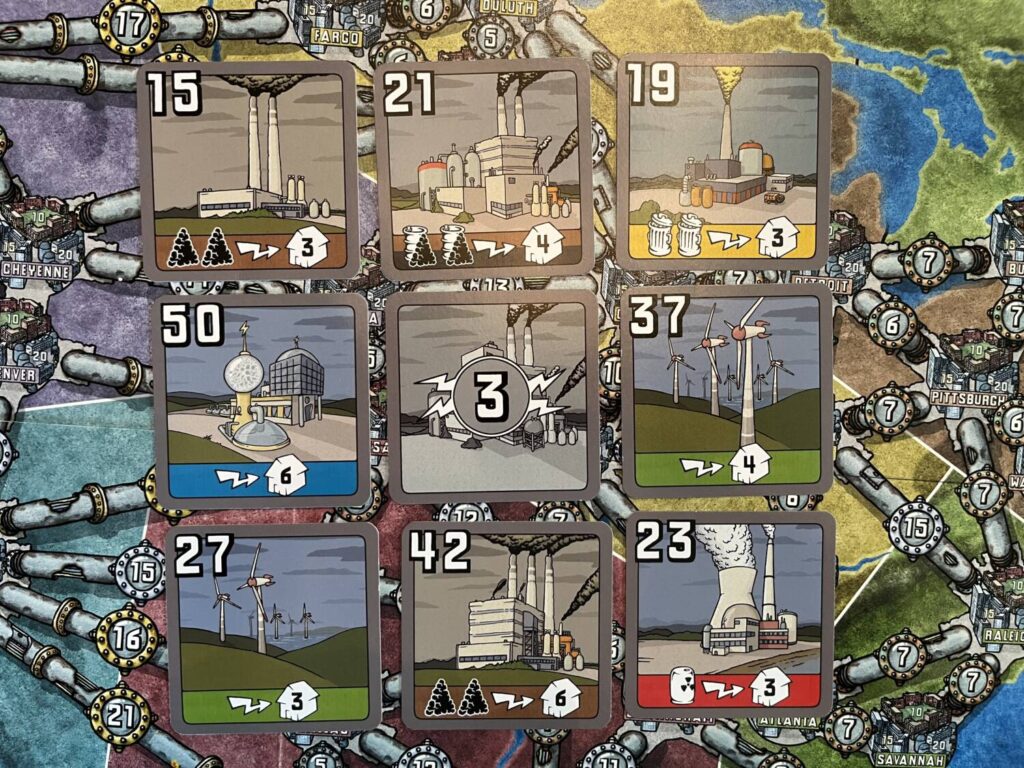

Take the square Power Plant cards and remove the cards with the numbers 3-10 in the upper left corner. Create two rows with them, with 3-6 on top and 7-10 underneath. The top row is the Active Row, where you can choose Power Plants for auction. The lower row is the Future Market with Plants that will eventually be available for auction.

Then find the 13 card and the card with a 3 on the face instead of a Power Plant and set them aside. Shuffle the remaining cards, following the rulebook guidelines for removing a specific number of Power Plant cards from the game based on player count. Place the 13 card face down on the top of the remaining deck and put the card with the 3 on the face on the bottom.

Randomly determine player order and place a building of your color in the upper left of the board to reflect that order.

Overload, Generator, Oscillator

Each round of play is made up of five distinct phases:

In the first phase, Power Plants are Auctioned off to all players. Of the two rows of Power Plant cards, only the cards in the top row are up for auction in the first two phases of the game. (More on this later.) The bottom row provides a preview of the card that eventually come into play in future auctions.

Working in turn order, the first player can choose to bid on a Power Plant. The minimum bid is the number shown in the upper left corner of the card. Bidding goes in clockwise order amongst players, with the winner of a Power Plant being ineligible to bid in other auctions in that round. Should the first player win the auction, the next player in clockwise order who has not won an auction bids first.

When someone wins an auction, replace that card with the top card of the face-down Power Plant deck. Place it face up, in numerical order, with the remaining Power Plants.

At any point in the game, you can only have three Power Plants. You can buy additional Power Plants, but if you already have three, you’ll need to give up one of your current Plants to make room for the new one.

When all players have either purchased a Power Plant at auction or passed, the Purchasing Fuel phase begins. The bottom left of each Power Plant card shows the type of fuel required to power that particular plant, with the number of cities it can power listed on the right. Note that while most Power Plants only use one type of fuel, some plants can use coal and/or oil to be powered.

The different types of fuel are in numbered areas along the bottom of the board. The number in the upper right corner indicating the price for each fuel in that section. This means that each coal in the first area costs 1 Elektro to purchase; each coal in the second area costs 2 Elektro to purchase, etc..

When purchasing materials, you may only purchase the material used by your power plants. (You can’t purchase the materials an opponent needs, but you can’t use.) You can, however, buy up to two times the amount your plant can use to power cities. This means, if your plant takes two oil to power two cities, you can purchase four oil. You’ll use two to power the plant on this turn and have two in reserve for the next turn. In this way, you can bank some materials when you get a chance to buy them at lower prices, as well as forcing your opponents to spend more money for the same resources.

The purchasing phase begins with the player with the fewest plants on the board (the player last in turn order for your first turn). You do not refresh these resources during the purchasing phase. If there is no oil left when it’s your turn to buy, you cannot buy any this round—and unless you carried over some oil from the previous turn, you can’t run that power plant on this turn.

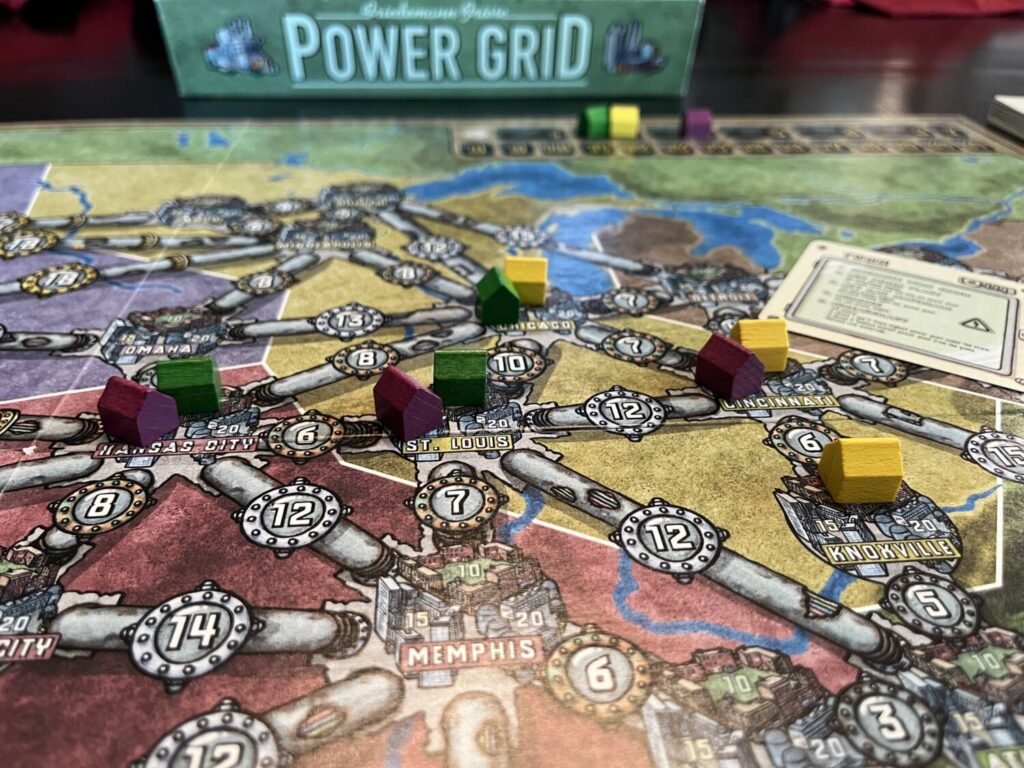

After you’ve bought fuel to feed your plants, you can start to build your network of cities by Building plants. Again, in reverse player order, each player can choose to build plants in as many cities as they wish, providing they pay the associated costs. Each city has a 10, 15, and 20 area. The first person to place a plant in the city only pays 10 Elektro to do so. In the later phases (again, more on those later) a second player can pay 15 Elektro to build in the city.

When you build in a city, your power plants power that city. When you expand your network from there to another city, you pay the connection cost on the pipeline connecting the cities, as well as the cost for the new city.

For each plant that you build, move your plant marker on the upper right track on the board and adjust the player order track. After the first turn, the first player is the one with the most plants on the board.

The last phase of a round is Bureaucracy. In player order, each player turns in the resources listed on the Power Plant cards they used to power their cities this turn and earn Elektros based on the number of cities.

Next, you’ll find the chart in the rulebook that tells you how many of each resource to resupply the market with. (Hint: it will never be enough.)

Return to the Power Plant cards and place the highest numbered power plant from the future market face down under the draw stack and draw a new card to replace it. Rearrange the market so this new plant is in numerical order.

Make a Circuit With Me

Phase Two

Phase Two of the game starts when a player builds their Xth plant on the board—a number that varies by player count (but is most commonly seven). At this point, a second player can build in a single city. To do so, they’ll pay the pipeline connection cost to the city as well as 15 Elektro to place a plant in the second spot.

Remove the lowest numbered Power Plant card from the active row and return it to the box. Draw the first card from the deck and place it in numerical order amongst the other Power Plants.

Review the resupply chart, as the numbers change with the start of the second phase.

Phase Three

Eventually, when resupplying the Power Plant market, you reveal the card with the 3 on the face. This signals the start of the Third and final phase of the game.

Each city may now have three player’s plants in them.

Shuffle the Power Plant cards in the remaining stack. These are all the highest value Plants that were removed at the end of each round during the Bureaucracy phase. Create a new market with two rows of three cards. During the remaining auction phases, there will be no Active and Future designations; all six cards will be available for auction.

Now, at the end of the Bureaucracy phase, instead of removing the highest value Power Plant card, you’ll remove the lowest and replace it with the topmost card of the deck.

Ending the Game

The game ends when a player builds a specific number of plants—14 to 21, depending on player count—connecting that number of cities in their network. Players complete that Building phase and go into one last Bureaucracy phase, one that is limited to powering as many cities as they have resources available to power. The person who can power the most cities is the winner.

On the Grid

Abram Towle

Power Grid was my third exposure to the world of hobby board gaming, following Munchkin and Small World. I remember sitting in a poorly lit basement with my friend’s family, trying to learn the most complex game I’d ever played in my life to that point. They all had clearly played this before, and I was doing my best to keep up. I did quite poorly and I distinctly remember making a distinctly expensive decision to establish a plant in another city to prevent myself from becoming boxed in.

Despite my losing effort, Power Grid was the final push that I needed to get into board gaming properly.

I was—and still am—enthralled with the visible representation of the component market and how its replenishment reflects the shift in the market away from coal. This carries into the auction phase as you weigh out which resources will be scarce, thereby costing more. It’s a simple and elegant way to teach the core concept of supply and demand.

Normally, I’m not that interested if a game has a bidding mechanic because it often leads to a source of anxiety in the form of hate-bidding. That’s my term for when a player drives up the cost of an item—in this case, a power plant—without having any intent to actually purchase the item. It’s a viable and necessary strategy that I will certainly engage in, but the resulting game of monetary cat-and-mouse turns the exercise into a social experiment.

In Power Grid, these bidding wars require so many more considerations and calculations. Players appraise the upcoming costs of how many raw materials they’ll require, how much money they’ll need for plants and expansion into other cities, and the cost of the power plant itself. There have been plenty of times where my master plan comes up one Elektro short because of a miscalculation in the bidding phase. But the game is often so tight that you need to squeeze value out of every Elektro on every turn.

Which leads me to my final point of praise for Power Grid, which is how much I love the Phase-based approach to the game board. By locking away cities until new thresholds are reached, the game always feels cutthroat. Cities are only available for so long before they get snatched up by somebody. And when they open up in a subsequent phase, it naturally creates a feeding frenzy over the limited real estate.

Even though Power Grid is more than twenty years old, it solidly stands as a brilliant template of Euro game design. You’ll agonize over every choice—not because they are difficult, but because if you don’t plan appropriately, it’s lights out.

Tom Franklin

Even though I have review copies of several games I need to get to the table, after writing the How to Play section above, I brought Power Grid to my weekly gaming group. According to BGG, we had last played it in 2014, which is way too long between sessions.

Despite my lengthy rules section, the game boils down to: auctions to buy new power plants; buy resources; build into more cities; power those cities and make money. After the first few rounds of getting used to the game again, our session of Power Grid played out quickly.

The auction phase is, perhaps, my favorite part of the game. Pushing the bids on a great power plant higher and higher—and watching the other players sweat just a little when they’re balancing their cash reserves—is always fun. When you’re bidding, you need to make sure you have enough money left over to buy the resources your power plant needs to power your cities. I’ve seen players overbid for a power plant only to find they don’t have the money to make use of it.

Building on the map starts out with only one person being able to build in a city. By the time the fifth or sixth city is claimed, your options for further expansion are limited, just as they are for everyone. Being able to outmaneuver an opponent by either blocking them out of an area or paying the connection costs to claim a city next to them before they can, is a great feeling. Even if it’s someone else doing that to you, you have to appreciate the cleverness of that plan.

Once the seventh city is claimed, a second player can build in an occupied city. This triggers a new building frenzy, one where you’re still trying to deny access to other players.

One of Friese’s best rules is a subtle one: there is a diminishing return on expansion. At the start of the game, you’ll be making 11 Elektro per city, meaning you’ll have extra money early on to expand. By the time you’re building in your 10th city, you’re only making 8 Elektro per city. You now have to work harder to balance the cash needs of expansion: you’ll need more resources to power more cities, but those resources become limited and more expensive.

Power Grid is a very solid game. To me, it doesn’t feel its age at all. The mix of mechanics and the adjustments that occur during the second and third phase of the game make for a good time of gaming decisions and rewards on each turn.

Andy Matthews

Power Grid was one of the first games I ever played which didn’t have a traditional player order. I was quite new to the hobby and got pulled into a 5 player game with experienced players. I seem to recall getting beaten pretty badly, but that didn’t diminish the shine from this game. Over the years since, I’ve come to understand that I really enjoy economic games, perhaps because they’re usually quite cut and dry. You have the money or you don’t, you can afford something or you can’t. And, in Power Grid, money is quite tight…in my first few plays of the game, you got used to hearing the riffle of the paper money being counted under the table as players tried to determine what they could afford.

Power Grid was also my first introduction to the genius of Friedemann Friese. Since I first acquired my own copy back in 2016, I’ve either purchased or played almost every other one of Friese’s games. And yet, Power Grid is still my favorite. Friese’s games have an unexpected quality in both theme and mechanisms that you don’t see in many other designers. Faiyum for example, is a deck building game where you never shuffle, and you’re forced to balance using powerful cards (which then go into your discard pile) with spending resources to recover those cards off the top of your discard pile. Or Free Ride, which has players building train routes across the continent (either Europe or USA) but encouraging other players to use those routes (thereby making them “free” for everyone else). Or even one of his most recent releases—the excellent Fishing—which presents as a trick-taking game that layers in elements of deck-building and cards with special abilities.

I think I’ll never get tired of Power Grid. And even though I don’t play it all that often, it remains not only my favorite game of Friese’s, but perhaps one of my favorite games in general. It’s not because I love paper money, it’s not because I have a particular interest in civil engineering, and it’s certainly not because I win every time. But I think it’s because when I do win a game of Power Grid, it gives me a real sense of having outsmarted other people at the table. And that’s the sort of glow you only get when the lights are on in a city that you powered with your own two hands.