Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

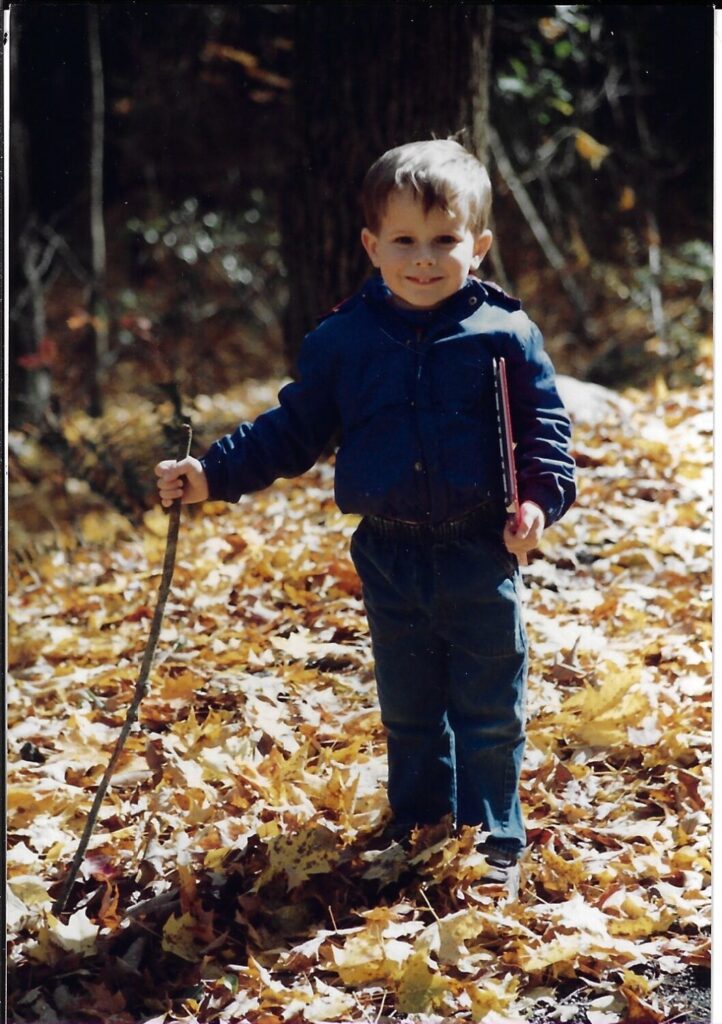

When I was a child, I would spend hours in the woods surrounding my New England home. My mom gave me a pretty long leash, and I used it. A pack of Toasty Peanut Butter crackers would go into my pocket and off I would go into the trees, to walk along the stream while poking and prodding.

My time there was spent half-lost in imagination and half-fully absorbed by the real world. I spent a lot of time crouched over the stream, watching the water striders. I was fascinated by the dents their legs made in the surface of the water, dents that I only later understood to be a result of surface tension. Though we had turkey, deer, and snakes in those woods, those water striders were about the biggest thing I ever saw. Spotting a chipmunk was a thrill. In retrospect, a lone eight-year old may have lacked the elegance and grace necessary to not scare away anything within hearing distance.

Most of my time in those woods was spent with the geography. A clay wall to dig into. A felled tree to climb across. Skunk cabbage, which I either thought or pretended—hard to say—you couldn’t step on, lest it would transform into swamp. Massive rock formations that simply must have housed bears. That forest, in reality nothing but a relatively small parcel of land, was endless. I spent ten years of my life in those woods and they continuously yielded discovery after discovery. The forest was inexhaustible.

Juniper Biscuits

Much as my adventures began with Toasty Peanut Butter crackers, Earthborne Rangers begins with a basket of homemade juniper biscuits.

This game is a massive undertaking, be that as a product from publisher Earthborne Games, a formidable design team of Fantasy Flight refugees led by Andrew Navarro, or as an experience. It is a narrative campaign intended to last 20-30 sessions—30-40 hours—by the same group of 1-4 players. It is not a game to play once or twice, it is not a game to pull out at a random game night when you’re trying to figure out what to do next, and it is not something to be played by a rotating group. Earthborne Rangers offers a sprawling, branching, satisfying narrative alongside an enormous sandbox that rewards your curiosity. Through relatively simple mechanisms, it gives players a space within which to express their personalities, their interests, and their desires. It does all this, and it begins with a woman handing you a basket of homemade juniper biscuits.

This game is a massive undertaking, be that as a product from publisher Earthborne Games, a formidable design team of Fantasy Flight refugees led by Andrew Navarro, or as an experience. It is a narrative campaign intended to last 20-30 sessions—30-40 hours—by the same group of 1-4 players. It is not a game to play once or twice, it is not a game to pull out at a random game night when you’re trying to figure out what to do next, and it is not something to be played by a rotating group. Earthborne Rangers offers a sprawling, branching, satisfying narrative alongside an enormous sandbox that rewards your curiosity. Through relatively simple mechanisms, it gives players a space within which to express their personalities, their interests, and their desires. It does all this, and it begins with a woman handing you a basket of homemade juniper biscuits.

You are freshly-minted rangers, and she has been your mentor for the last nine months. She hands you the basket, the biscuits so fresh that they’re still steaming, and asks you to deliver them to a friend nearby. This is the prelude chapter of Earthborne Rangers, an introductory session that walks you through the mechanics of the game and the process of building your own Ranger Deck, so if you’re here, you presumably haven’t played before. “Biscuits,” you might think. “How cute.”

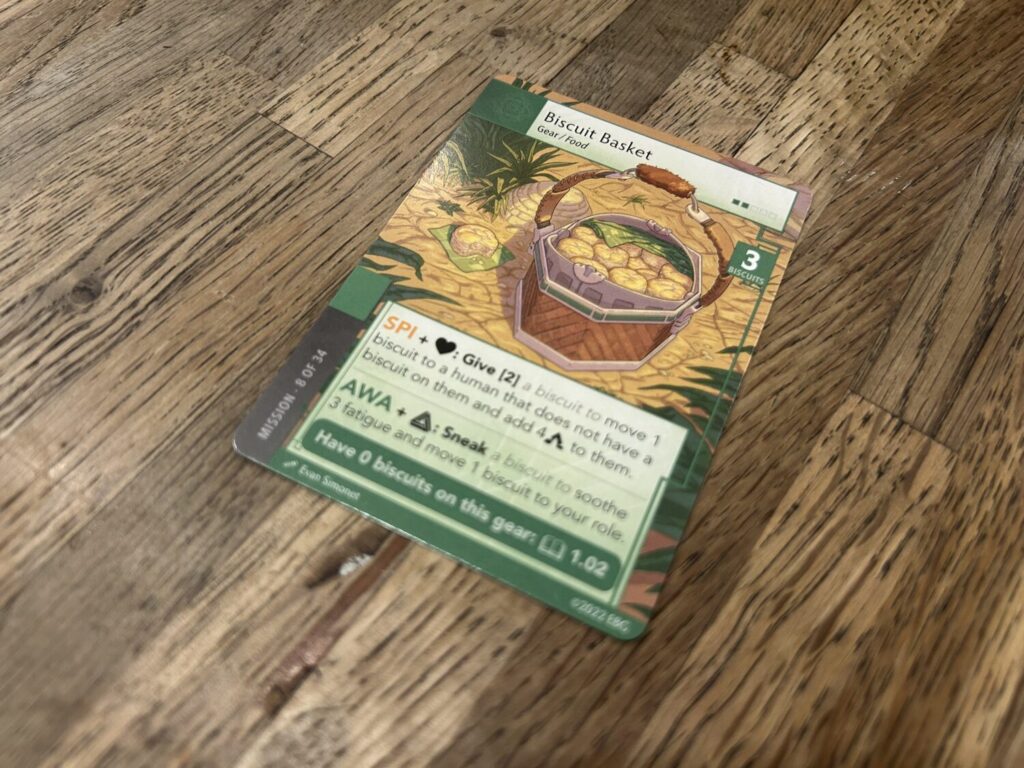

You would be right, the Biscuit Basket card is indeed cute. What you don’t know yet is that the Biscuit Basket card also shows off just about everything that’s great about Earthborne Rangers.

First, and immediately, there’s the art. The basket is cute, something I would gladly take on a picnic, but it also manages to be distinctive. It is recognizable and familiar as a basket, but it also doesn’t quite look like any basket I’ve ever seen. It establishes the mature design aesthetic of Earthborne Rangers, an early signal of the solarpunk influences that bloom into full view as you continue along. Even the fact that the top of the handle was formatted to stick up past the bottom border of the information bar at the top of the card is, with hindsight, appropriate. It suggests a dynamism, a world coming to life.

Then you notice that you’re meant to put three “Biscuit” tokens on the card. This is your first indication that Earthborne’s generic tokens can and will be used to represent just about anything. Biscuits in a basket are only the beginning. Berries in a net, sketches in a notebook, and bats in a colony all wait further down the path. Functionally, mechanically, they’re all the same token, but Earthborne Rangers always says what the tokens represent in any given situation. That allows for efficient specificity, using one token for many things without sacrificing immersion. A lot of games would either under-specify by calling them Supply Tokens, or they would give in to crowdfunding mania and include actual, specific Biscuit tokens. Not so here. They’re biscuits. Later they’ll be batteries. Earthborne Rangers chooses to use its imagination in a way that frees you up to do the same thing.

Finally, you read the two actions in the bottom text block. One, “Give a biscuit,” allows you to feed some biscuits to the people you encounter in the Valley, strengthening your bond with them. The other, “Sneak a biscuit,” allows you to eat a biscuit on the sly in exchange for a light bit of healing.

It seems like you’re being presented with three choices here: deliver the biscuits as asked, give the biscuits away to a third party, or eat the biscuits yourself. Not that you need to decide right now. She gave you the Biscuit Basket. It’s yours to do with what you will.

Tests, or, Mechanics

This is as good a time as any to explain Tests. You can more or less correctly think of “Test” as a stand-in for “Action.” On your turn, you either play a card, perform a Test, or pass. Most of the time, you perform a Test. There are many, many, many Tests in Earthborne Rangers. The aforementioned “Give a biscuit” and “Sneak a biscuit” are Tests. Most cards include a unique Test of one variety or another, and you have four basic Tests available to you at all times.

Every Test is connected to one of four Aspects: Fitness, for physically strenuous actions like fighting and hiking; Spirit, for connecting with the people and creatures around you; Focus, for actions that require precision; and Awareness, for paying close attention to your environment. To perform a Test, you have to spend at least one Energy in the corresponding Aspect. If you have more, you’re welcome to spend more. It increases the chances that you’ll succeed.

Let’s say I decide to sneak a biscuit. I pay one Awareness—you can’t sneak a biscuit without being sure that nobody’s watching, after all—and decide that should be enough. Then I flip over a Challenge Card. The Challenge Cards include a modifier, either positive or negative, for each Aspect. The lowest possible success threshold for any Test is 1. If I reveal a 0 or a positive number, I’m good. It worked. I biscuited.

If I flip the top card over and it’s a -1 or a -2 for Awareness, things don’t go well. Maybe one of my companions asks me a question right as I’m about to stuff the baked good in my mouth. Maybe I trip on a rock and the biscuit goes flying into the nearby stream. Success is nowhere near guaranteed. They’re called “Tests” because you can fail.

You don’t have a ton of Energy in any one Aspect. The upper limit is generally 3. Since most tests have a success threshold of 2 or higher, and there are -2’s floating around in that Challenge Deck, you will often find yourself wanting to increase your chances of success. That’s when Approach Icons come in.

There are four Approach Icons, corresponding to Conflict, Reason, Exploration, and Connection. Every card in your deck has at least one or two along the left side. Every Test calls for a specified combination of Aspect and Approach. One Energy is required, but more than one Energy is fine, and if I really wanted to make sure I could eat that biscuit, I might discard a Reason symbol or two. After all, why not? Why shouldn’t I keep the biscuit?

The recipe for each Test is another way in which Earthborne Rangers brings great specificity to a fairly straightforward system. We’ll talk more about the deck-building process for each Ranger later, but know that you choose a background and a personality for your character, and those choices are reflected in the Aspects and cards you have available. Someone who struggles to connect with other people probably isn’t going to give a stranger a biscuit. Someone who is clumsy and awkward probably wouldn’t manage to sneak one without anybody noticing. Tests are the Biscuit Tokens all over again. They help create a world that allows for incredible flexibility and specificity within the confines of a fairly constrained—but not constraining—system.

The Valley

The Valley is populated by plants, animals, structures, mythical creatures, ruins, secret pathways, and annoying children. Each and every one of them are found in the Path Deck, which is created anew every time you change locations. The recipe for the Path Deck is simple: as you move from A to B on the map, you cross over one of several types of terrain. You might have taken a mountain pass, or walked by the lakeshore. You could have gone on a lovely stroll through the woods, or a nightmare canoe trip up the river.

The Valley is populated by plants, animals, structures, mythical creatures, ruins, secret pathways, and annoying children. Each and every one of them are found in the Path Deck, which is created anew every time you change locations. The recipe for the Path Deck is simple: as you move from A to B on the map, you cross over one of several types of terrain. You might have taken a mountain pass, or walked by the lakeshore. You could have gone on a lovely stroll through the woods, or a nightmare canoe trip up the river.

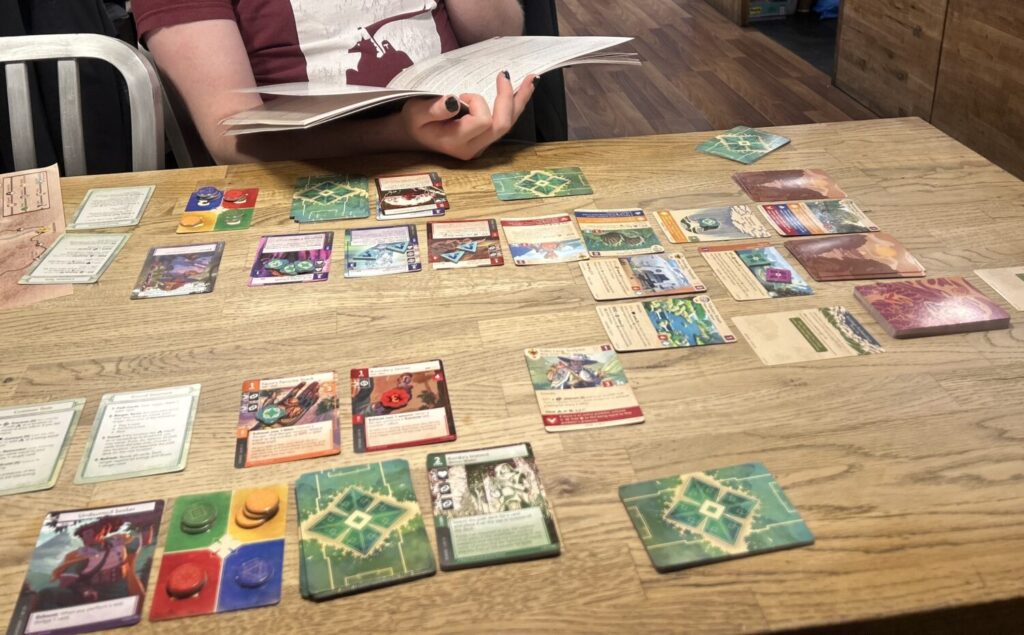

However you got where you are, you take the appropriate Terrain Set and shuffle it together with whatever cards the location itself calls for. For as long as you are in that location, each player draws one card from the Path Deck at the beginning of each round. Some of those cards are placed Within Reach of the player, meaning they go right in front of you. Others go Along the Way, a sort of common area between the players. Regardless of what you draw, be it alive or inanimate, every card in the Path Deck fosters interaction of some kind or another. Deer can be scared off. Ruins can be explored. Annoying children can be asked very nicely to go away.

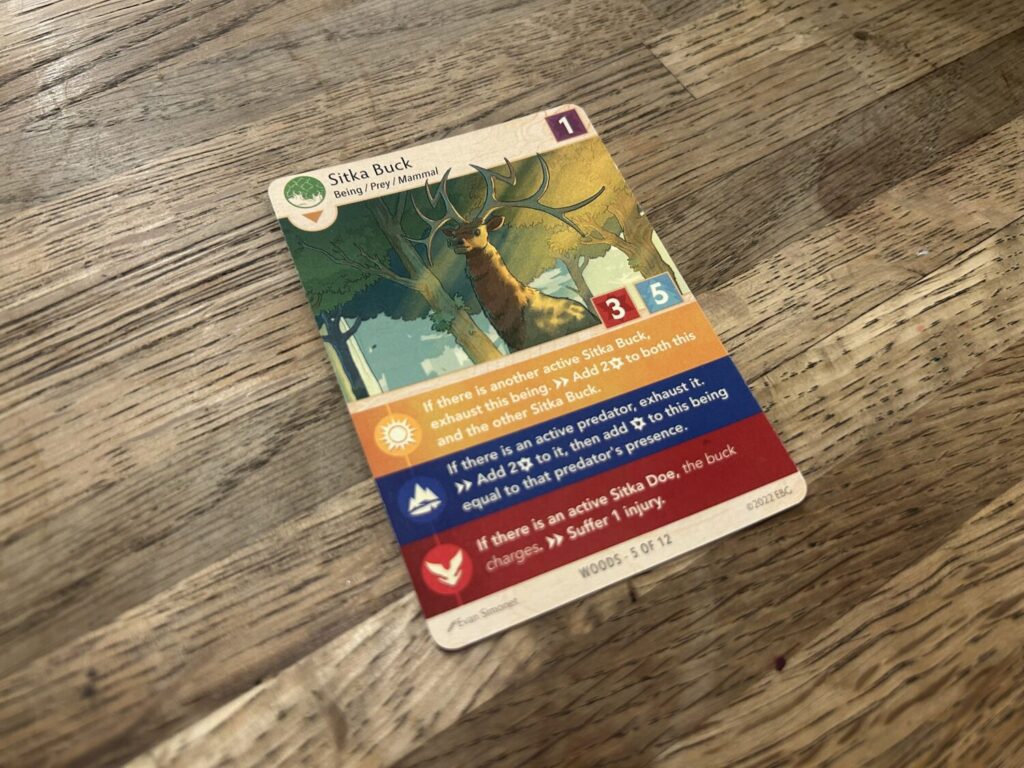

Pretty early in the game, you will come across the Sitka Buck. He doesn’t have any custom Tests on him. You could easily leave him alone. He’s not interested in you, and won’t really get in your way. But the moment another Sitka Buck appears, or a Predator of any kind, or, god forbid, a Sitka Doe, he springs to life.

The colored bands on his card correspond to symbols at the bottom of the Challenge Cards, and the indicated effect triggers whenever a matching Challenge Card is revealed. If I draw a sun, and there’s another Sitka Buck on the table, they run at each other. If I draw a mountain, and there’s a predator, the Buck charges at it, harming both animals in the process. If I draw whatever the red symbol is and there’s a Sitka Doe, the Buck charges at me, and I take an injury. If you get three of those in a single session, the game immediately ends so you can camp and tend to your wounds. By himself, the Sitka Buck is cute. In the context of the Path Deck, as you start to explore the area and discover more of the woodland, the card vibrates with possibility and uncertainty.

The colored bands on his card correspond to symbols at the bottom of the Challenge Cards, and the indicated effect triggers whenever a matching Challenge Card is revealed. If I draw a sun, and there’s another Sitka Buck on the table, they run at each other. If I draw a mountain, and there’s a predator, the Buck charges at it, harming both animals in the process. If I draw whatever the red symbol is and there’s a Sitka Doe, the Buck charges at me, and I take an injury. If you get three of those in a single session, the game immediately ends so you can camp and tend to your wounds. By himself, the Sitka Buck is cute. In the context of the Path Deck, as you start to explore the area and discover more of the woodland, the card vibrates with possibility and uncertainty.

The uncertainty of the Path Deck makes the entire world of Earthborne Rangers come to life. Every card reveal is exciting. It could be good. It could be disastrous. It could be funny! We could be making our way through a perilous mountain path when Sil Belai, Artist appears. Why is she there? I don’t know, she probably liked the lighting. Talk to her a little and you’ll find out that she’d love for you to pose for her. But we don’t have time for that right now, Sil! We have to get you to the other side of all these loose stones before the whole path gives in and you get hurt. We already had our hands full trying to shake the Circling Irix flying overhead. Terrific.

The Path Deck is incredible, an inspired piece of design. I experienced a jolt of excitement when I realized that it didn’t just contain threats, perils, and obstructions, but why would it? Those aren’t the only things you bump into when you wander. Every draw off the top of the deck represents another set of steps, either yours or someone else’s. That means you don’t always know exactly where to find things, but that’s okay. Where was that ruin? I know it was around here somewhere…maybe if we just walk a bit more. The Path Deck makes the whole of Earthborne Rangers feel more alive, more vibrant, like the world isn’t sitting there waiting for you.

On Rangers

One of the great things about RPGs is the freedom to create your entire character. You can decide who you want to be, who you have been, and what you want to do. You have complete authority over deciding how that individual interacts with the world around them. Earthborne Rangers is a card game. Your character is, in essence, a deck of pre-printed cards that have to be able to interact with other pre-printed cards. That means there are inherent limitations on how much freedom the game can afford you, but it is done in such a way as to make those limitations all but disappear.

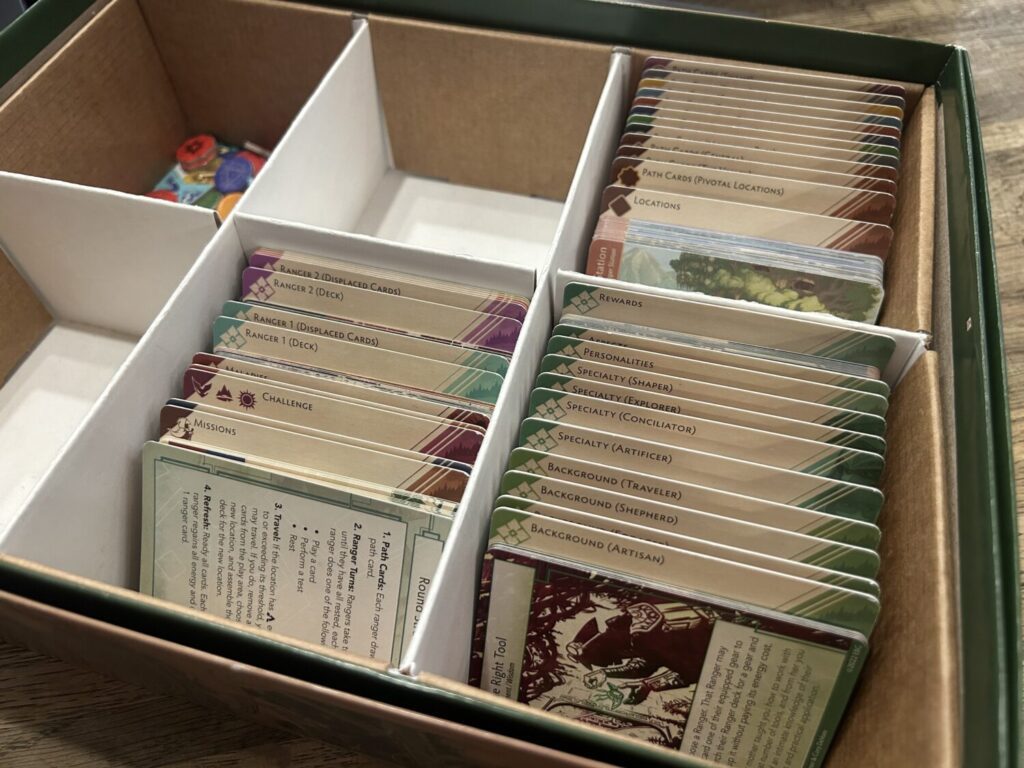

You begin a campaign of Earthborne Rangers by constructing a deck. Over the course of the campaign, you will unlock rewards that can be swapped in, and there are many opportunities to adjust your deck if you find it lacking, but your choices here set the tone for the story ahead.

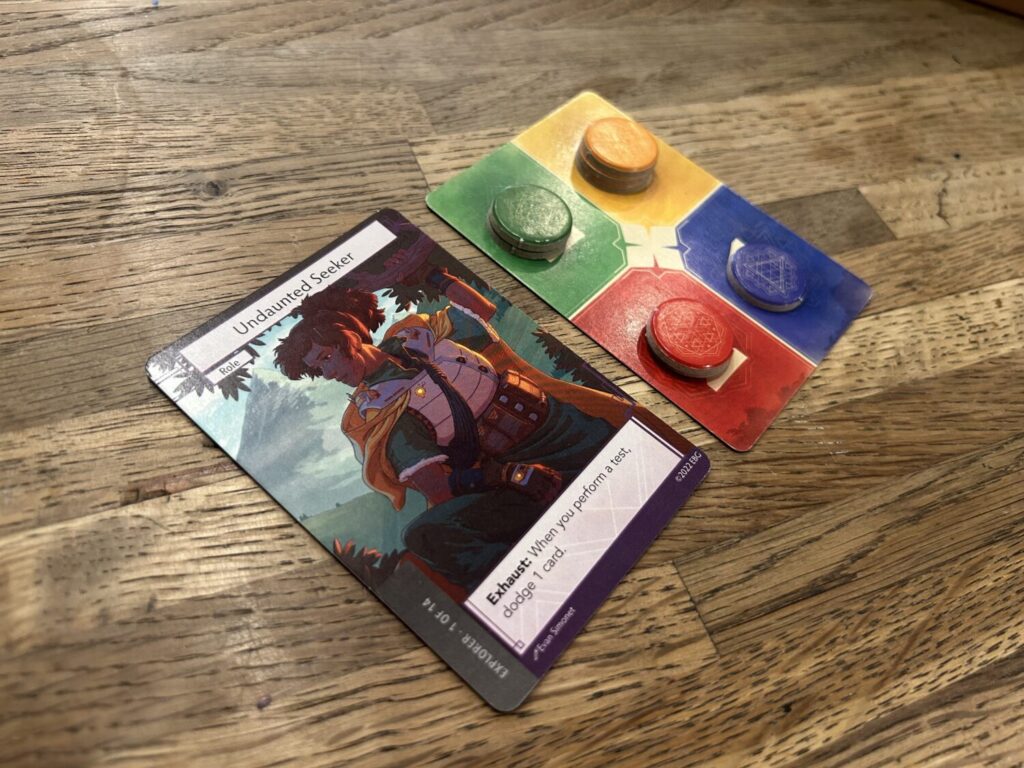

First, you choose your Aspects Card. This has enormous influence on how you play the rest of the game, since it determines how often you can perform certain Tests. One Aspect will refresh to 3 Energy every round, while another will only produce 1. Over the course of a campaign, you come to notice or curse all of the moments that would play out differently but for a different choice of Aspects.

After that, you choose Personality, Background, Outside Interest and Role cards. There’s oodles of theme and setting within this. If you and your friends are people who enjoy role-playing, your choices can serve as guides, but the real beauty of this to me is how role-playing is baked into the mechanics. Even if you don’t have an ounce of imagination in your body, the choices you make here influence what’s available to you. If you select a Traveler who specializes as an Artificer, you will often deal with situations in a way appropriate to that character.

I built my Ranger entirely by choosing the things that felt most like how I’d want to interact with this new world. I knew in my first campaign that I wanted to spend a lot of my time talking to people and befriending deer, so I chose a card with high Spirit and low Focus. I chose to be a Forager who specializes in Exploration, because I was excited to poke around the bushes and the trees and snack on some berries. And let me tell you, that’s exactly what I did.

Exploration

It would be possible to write an exhaustive and praising review of Earthborne Rangers that engages with it as a series of mechanisms. This review, in fact, engages with its mechanics more than I’d like, but sometimes that’s necessary. Earthborne Rangers is an incredibly satisfying game in just the mechanical sense. There were dozens of times when my friend and I would figure out some extremely clever and satisfying play to get out of a jam, or managed to wriggle our way out of something because one of us happened to have the perfect card, but not once did we feel like we were stuck because neither of us had the right cards. In a game like this, with all the ways in which the world can unfold, that’s frankly astonishing.

It would also be possible to focus on it as a narrative work. The main story unfolds at a perfect pace. It challenges you without pressing you. The structure is such that it ebbs and flows. Certain sessions are spent more focused on the main story while others feel more open to poking and prodding. The “boss fight” missions—there are no bosses, of course, but there are more intensive tasks—were challenging and satisfying. When we arrived at the conclusion of the main story, we could tell. Not because the game told us, but because it felt like a conclusion.

The more I think about it, the more I believe that Earthborne Rangers is right to start with those juniper biscuits. They say a lot about the game and its intentions. There are many narrative games in which the biscuits would be negligible. Deliver them, or don’t. Eat them, or don’t. Whatever. Delivering them to their destination might get you a little money, eating them might get you a slightly different text box out of the narrative book. Either way, you’d still go from the place where you get the biscuits to the place where you’re meant to deliver them and proceed from there. That was my assumption about Earthborne Rangers, too.

Here’s the thing: you don’t need to deliver the biscuits at all. Delivering the biscuits helps lead you to the main storyline, a storyline that can readily support a full-length campaign, but upon revisiting the card as a part of writing this review, I realized with a jolt that I could have munched them down, run off into the woods, and never again encountered the A plot in any substantive way. It would still be happening around me, as Hamlet permeates Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. I would still be able to opt in from time to time, but it would rarely if ever be forced. Earthborne Rangers is structured in such a way that it will point you in one direction or another, but it’s only pointing. You can walk in a different direction.

What’s more, the things you’d find to occupy your time otherwise are great. The main story of Earthborne Rangers is excellent, I highly recommend it, but the Valley is littered with wonderful side quests in which you could and can easily lose yourself. We spent an entire session chasing down a mythical creature who kept disappearing into the trees. We took a boat upstream to a secluded location entirely because it was secluded. It was open world video game logic. If I can see a far off cliff tucked behind a waterfall, there better be treasure there. Never once did a side trip feel like a waste. Our curiosity was always rewarded. Sometimes that reward was a new piece of gear, but just as often, it was a cool discovery, like etchings on a wall that added to the sense of a world inhabited. Everything pays off.

Earthborne Rangers is both an excellent card game and a fine narrative achievement, but first and foremost, it is a profound celebration of exploration, nature, and curiosity. I was carried away by it. It is political without preaching, it is spiritual and joyous. It connected me to a time and place in my life that I realize now I don’t spend enough time thinking about. I was back in the woods of New England, watching water striders and digging through clay. It’s even right there in the manual, which I didn’t notice until after having written the bulk of this review. The first six words of the Earthborne Rangers rulebook are, “This is an invitation to explore.” You’d be crazy not to accept.