Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I never wanted to start a review like this, but we here we go: I’ve been thinking a lot about the ways in which board games and capitalism are intertwined. Mea culpa, mea culpa, etc.

Hear me out. I’m not talking about the industry, though lord knows there are plenty of things to reflect on there. Nor am I about to lay down a screed on board games as a heavily consumerist hobby, the “Why I’m Leaving New York” of board game writing. I’m not even talking about the textual settings. Of course Brass is about capitalism, or at least embodies it. If I were going to write about that, I might as well open with “Did you know Monopoly was originally designed as a satire?”

No, what I’ve been thinking about is the ethos of games in general, and how they often reflect two core principles of capitalism. First, there’s the idea of abundance as it exists within the framework of games like Catan. You have to carefully mete out how you use the resources you have, yes, but there is no sense of consuming resources from an ultimately finite pool. If you roll a six, you get some wood, and for as long as sixes are rolled, that will happen. The island itself will never stop bearing fruit. The sheep will never run out. The stone quarries go on for an eternity. If you bump into the Balrog, tell him I say hello.

This is even true of scarcity games like Agricola. Your farm might be in trouble, but next turn the market will contain more horses, more wood, more stone. The system has always and will always provide. Moderation and sustainability aren’t concerns.

I’ve also been thinking about the endgames of designs like Smallworld and Root, how they don’t ask you to consider the long term viability of your final position. Board games are often about a communal balance, even if we aren’t thinking about it that way. Not to say it isn’t everyone-for-themselves out there on the table, but in making sure one opponent doesn’t manage to secure every resource or space or route, I am leaving space for not only myself but others to continue playing, existing, and succeeding. Ensuring my success and the sustainability of that success keeps everyone in check.

In Root, if a player sees that 30 point threshold is in reach, they will often leave the board in a state that would be an absolute disaster for their faction were the game to continue. The game doesn’t continue, of course, so that doesn’t matter, but it’s interesting to me that the balance of the game, of the collective experience, is chucked out the window in the name of victory. In Small World, you don’t care what happens after your final turn. It’s all about spreading as far and as thin as you can, making as much money as possible. The consequences can be damned because, within the confines of the game as described, they don’t exist. The units you immediately lose are irrelevant.

The real world doesn’t work that way, even if it works that way for you. If you go to extremes to achieve something, the lives of the people and the materials that were collateral don’t suddenly stop. Your units matter independent of your will, whether you acknowledge that or not. The forest isn’t infinite.

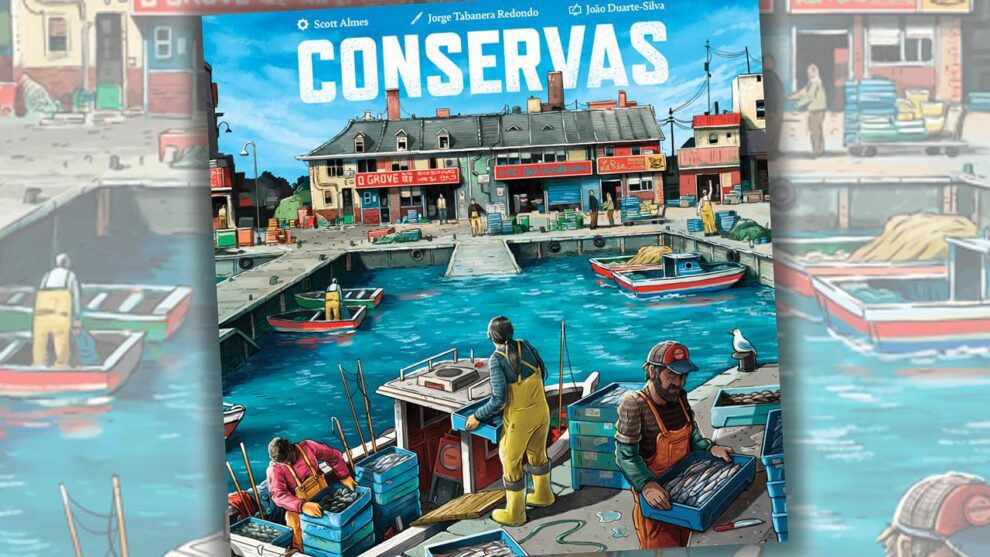

I have been thinking about these things because of a small box, 20-minute solo game called Conservas, from designer Scott Almes and publisher Salt & Pepper. It’s a sweet little bag builder, full of fish tokens and boat cards. You start by filling the bag with a specified maritime population, diluted by sea water tokens. Each round, your fleet of boats sets sail, casts its nets, and catches what providence provides. Catches are drawn five tokens at a time, and assigned to either a specific boat or, once per round, set out to the open ocean. Caught fish can be traded in for operation upgrades or sold to canneries, where the fish become tinned conservas.

You make money from the sales, but you can’t win Conservas by only thinking about the fish you catch. Those you release into the ocean each round reproduce, adding fish to the bag and increasing your chances of catching a good yield in future rounds. The entire game is about this delicate balance, upscaling your operation at just the right rate of speed to achieve your scenario-dependent financial goal while also trying to keep the whole thing sustainable. You have to draw five tokens per boat in your fleet, and overdrawing the bag adds more water tokens. If you have to add water tokens that aren’t there, you lose.

Most importantly, you can make as much money as you want in Conservas, but it won’t matter if there aren’t enough fish left at the end of the game. The welfare of the species matters as much as your money. You can’t win unless your operation is sustainable, unless you conserve. Conservas is a tight, tense, fun game, one that I had a great time playing. It also happens to be, in its own quiet way, a game with real things on its mind. Designer Scott Almes departs from board game tradition by suggesting that what comes after the game should matter just as much as what happens during the game. It’s a lesson we’d all do well to learn.