Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

I love stock games. I think this is part of why I love 18xx games so much—there’s money involved, but there’s also a big chance to both win and lose a lot of money based on the decision space.

The concept behind buying low and selling high is also why I love games as varied as Stockpile and supply-and-demand games like Brick & Mortar. Even in games I don’t necessarily love, such as Horseless Carriage—a game that featured a large amount of polyomino-style puzzling before getting to the part that I enjoyed, selling of cars in the market—I can find something that my brain really enjoys.

Bear Raid (2022, Allplay) is a game that, on paper, does the things I want in an economic simulation. There are stocks to buy, tied to markets that can be manipulated thanks to an interesting dice mechanic. Just having dice at all is a good thing, because, well, dice. The box says that Bear Raid has a 60-minute playtime, also a winner. There are stock splits and shenanigans and wacky artwork and funny company names. You can even spread rumors, which initially sounded like that would be a blast.

There are also event cards, for which I have mixed feelings, not just Bear Raid. The wacky art did not lead to wacky play, which was surprising. And the player count of five seems to be lower than the initial release of the game, in part because at six players, the game’s length was a major problem. (I don’t think five players helps with this issue, based on my single play.)

My discussion of Bear Raid here is tied to a single play of a five-player game. I have a lot of random thoughts that I will try to align with three areas of the design: the simplicity of the ruleset versus the difficulty players had conceptualizing certain economic concepts, the event cards, and the “take dice” action.

Let’s Talk About Money

I really enjoyed the film The Big Short. The performances are incredible and the film moves at a nice clip, but I mostly enjoyed the film because it did a good job of dumbing down the concept of “shorting” a stock for someone who doesn’t have any formal training around markets and how they function, particularly as it relates to something that can be so dangerous to the financial world. The term that sticks with me, either through the movie or my own research, is the concept that borrowing shares through a margin account features “limited profits and unlimited risk.”

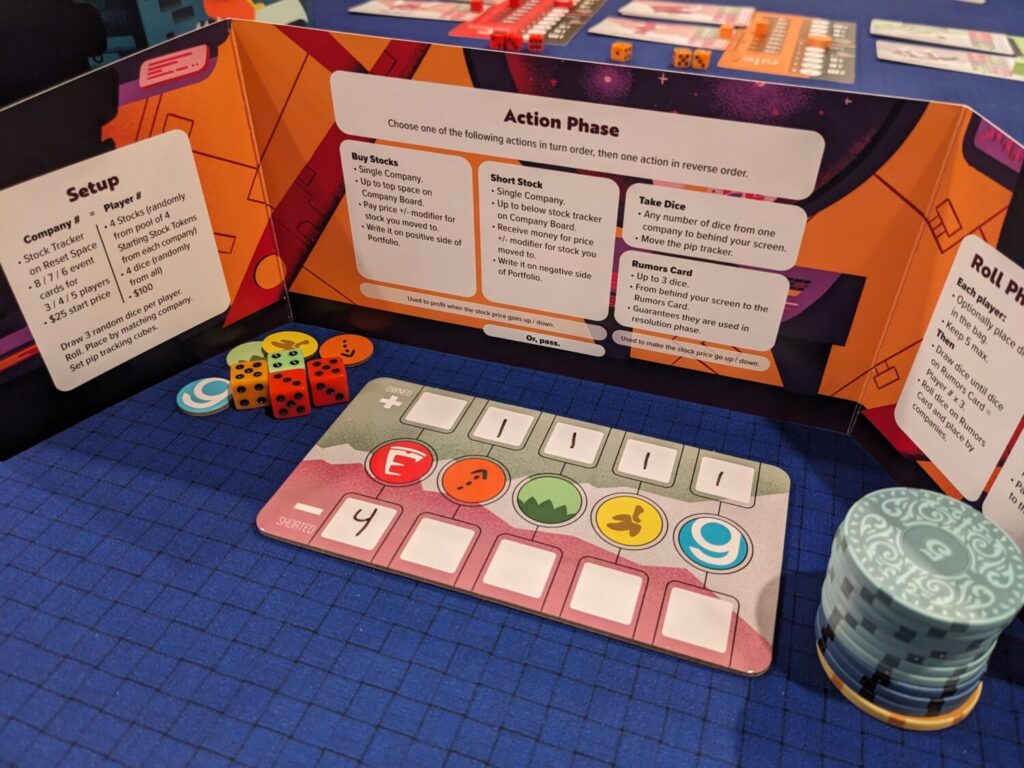

In the game Bear Raid, 3-5 players try to make the most money by buying and shorting stock. Over a variable number of rounds aligned with player count, players take market actions and manipulate dice—dice drive share prices up or down, depending on event cards assigned to each company included in the game—before those dice are re-rolled to adjust prices, potentially bankrupting a company or even driving stock splits. At the end of the game, players receive money for the value of any shares owned and pay money for any shares currently on the “short” side of their Portfolio Board.

Both in Bear Raid and in real life, “short selling” is risky—an investor is taking a loan on a company’s stock in the hopes that its price falls enough to buy shares of that same company later to make a profit. For those who followed the Gamestop short sell saga (also well documented in a film, Dumb Money), you have some familiarity with how this all works, and how this can destroy an investment company if they make a gamble that goes sideways.

So, just getting players to understand the concepts in Bear Raid can be tricky. Ideally, you want to short a stock that is currently very valuable, which grants the player a loan based on the current price. Then, you want to manipulate the share price of that stock so that you can buy shares of that same stock on a later turn for less money—ideally, MUCH less—than you got when shorting it. In a perfect world, you would short sell at $40 or even $45 per share (near the top of the market for a share in Bear Raid), then drive that company into bankruptcy, in which case, you wouldn’t even have to buy back those shares because the balance sheet is wiped clean—everyone who had a position in a bankrupt company loses owned shares or is off the hook for any shares shorted of that company.

Our game didn’t feature any bankruptcies, which was a shame because I think that would have added to the tension. I’m sure experienced players, who have a better understanding of the way event cards work, would be better at finding ways to bankrupt companies, because that clearly felt like the way to make the most money in Bear Raid. A free loan, that might be worth as much as $300 or $400 dollars and wouldn’t have to be paid back by buying shares if that company went bankrupt with that much “red” on the balance sheet? In this game, that might win the game.

Two of the five players in our game really struggled with the concept of taking a loan by shorting a company’s stock. That certainly hurt their experience, but I think it also affected the entire table. If some players know that they should be shorting a valuable company by buying lots of shares (pushing to drive its price down), but others don’t understand what that could mean for their end-game score, that hurts everyone.

One player, on multiple turns, was taking very inefficient actions—”I’ll short one share of Gazillioon for $20”, to later rebuy the share at $10 or $15. I think certain play groups who think they like or understand economic games will struggle with the differences between owning shares and selling owned shares, versus short selling then buying back those shares on the cheap.

The Event Cards

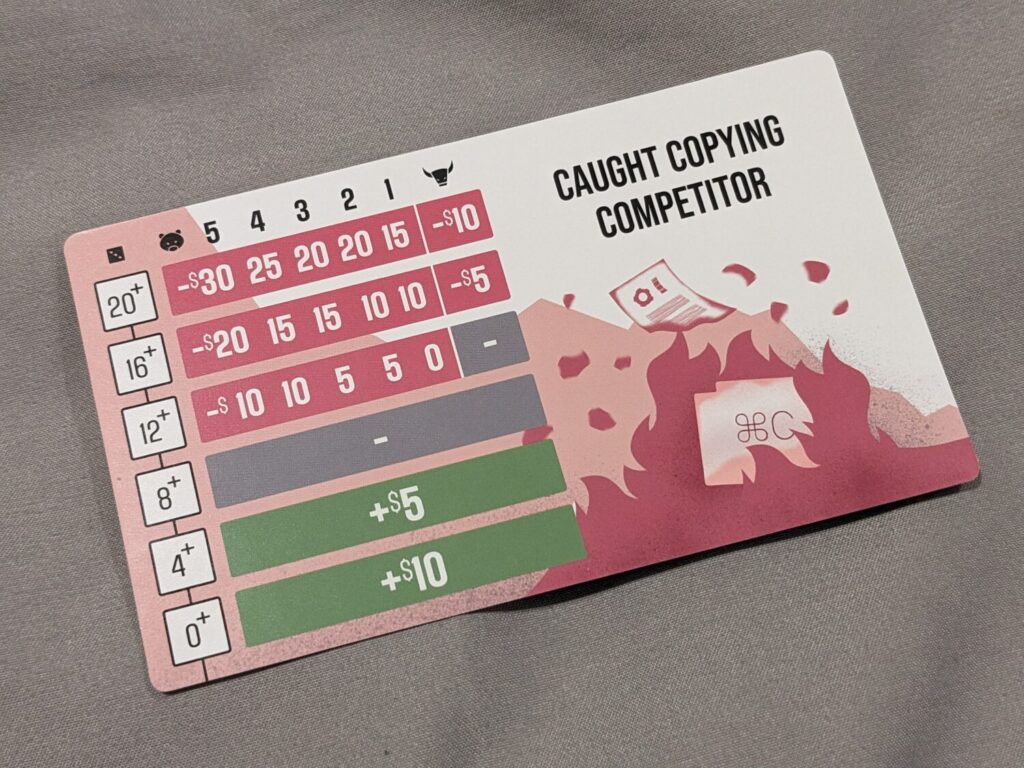

I love the event cards in Bear Raid, I really do. The artwork, the way the cards boost or devalue a company’s shares, and the clear way that icons inform the player on what the cards will do, all of that is great.

Understanding how event cards affect the current turn versus future turns is a little harder. Comprehending what ten of those cards mean, all at once, is harder still.

At the start of the game, a face-up event card tells the players what certain pip values will do to a company’s share value at the end of the round. (Thankfully, during a round, stock prices do not change.) In a five-player game, there are six rounds, so there are six event cards aligned with each company during setup. Players can see the current event card, as well as a preview of the next round’s event card. The die values will apply to the current card when the stock price is updated near the end of each round, and may affect how players plan into the upcoming round.

We found this concept to be quite interesting, but exceptionally volatile. The information is clearly there, but studying each card every round was more taxing than I expected it to be. Maybe it was my seating position; maybe it was the fact that dice are constantly moving around, between players who are taking dice from a company’s dice pool behind their player screen (which we will come back to), or when players are moving dice from behind their screen to the Rumors card, which guarantees that they will be rolled in the upcoming dice phase.

Each event card shows what will happen based on whether that company finds itself in a bear market versus a bull market. (In Bear Raid, this is separate for each company, so Edison might be in a bear market while Unusual Oil might be in a bull market.) Everyone spends the round jockeying to make a company end the round in a very specific line of each event card, with each card bracketed by pips in six different value areas.

For such a straightforward game, I was surprised at how complex this operation became each round. That also meant that I found myself concentrating on just two or three of the companies, not all five in our five-player game. I tried my best to align with a strategy that was tied to boosting a company’s value, ideally to $30 or more per share, then shorting that stock, then trying to manipulate dice enough to to drop its share price to $15 or less over the next 2-3 rounds to buy the stock back at a cheap price. (I found that trying to bankrupt a company, especially on my own, was a bit too obvious for the other savvy players at the table.)

The event cards in Bear Raid are cool, but a lot of work to stay in front of, at least in my very limited experience. I may never know what it is like to sit at a table with four other experienced Bear Raid players, but something tells me that is the game’s sweet spot.

“Who’s Hoarding All the Yellow Dice?”

One of the actions a player can select during their turn allows them to take any number of the dice assigned to each company behind their player screen. Each company begins the game with eight dice, which are rolled to set expectations for what will happen at the end of that first round. Dice are only rolled at the end of each round, and only if they are not currently attached to that company’s dice pool.

That means that if no one takes an action to remove dice from a company, the value rolled at the start of the game will be the only value they ever see.

I liked what I saw with the yellow company, Banana, at the beginning of the game. The price was going to go up by $10 if no one took any dice from their first event card, and the preview card aligned with the idea that if someone took most, if not all, of their dice, their share price would go down at the end of round two. As I expected, no one took any of Banana’s dice away, so their price went up to $35 per share in round two. I was the first player in the next round, so I shorted five shares of Banana to earn a handsome short-term loan, then on another player’s turn, they took all of Banana’s dice away, ensuring that the price would drop for the next round.

Little did I know at the time that this player would keep five of Banana’s dice behind their screen for the rest of the game. You can do that! Severely limiting Banana’s planning prospects, I pivoted to other stocks, but I was surprised that a player could simply take a company out of play by hoarding dice for the entire game. The game’s rules allow for a player to keep no more than five dice behind their screen…which we all did.

That meant of the 40 dice in the game, 25 of them were usually behind our collective player screens. And not once, during the entire game, did a player use one of their actions to put dice on the Rumors board, which would guarantee that they would be added to a company’s pool on the next round. (Each player gets just two actions per round.)

The rules are the rules, and if that is what designer Ryan Courtney (Pipeline, Trailblazers) went with, that’s what we are left trying to evaluate. But it feels like being able to hold so many dice from round to round limits the amount of interesting decisions tied to each company. It also meant we had two rounds where less than five dice were re-rolled then added back to companies to potentially adjust prices. In a dice game, I want to chuck said dice, rather than not chuck the dice because they are being hoarded by a neighbor.

Insert the Wacky

Bear Raid’s cover, with what looks like a bear and a goat on puppet strings, fighting each other, gave me the impression (hope?) that it was going to be bonkers. I was expecting wildly fluctuation in stock prices, multiple bankruptcies, stabby play, and events that might send stock prices, Gamestop-style, into the stratosphere.

My findings after our first play? Mild fluctuations in stock prices, conservative decisions, and occasional chances to make $20 or $30 here and there. I found myself standing for most of the game as I considered what would happen to each company’s price when the round was over based on the buying and shorting activity during a round. A couple of times, I was hoping to roll three dice per player, and found myself with an empty bag and no real drama tied to that concept.

That left Bear Raid in an interesting place. I liked what Bear Raid was going for, on paper. It’s a very easy rules-teach but a somewhat challenging discussion around financial concepts. The game took about 90 minutes to play after I taught the game to my group; that is longer than the time on the box, but I didn’t mind that as much as I minded the lack of a truly dramatic arc from round to round. In most rounds, prices moved up or down by $5-$10 per share, per company. In one round, Gazillioon had a price that boosted above $50, which meant a stock split for share owners (which also meant anyone who had shorted that stock suddenly increased their risk exposure by double!), which was a fun moment because three players worked together to ensure that the price would ride over the splits threshold.

Bear Raid is worth a look. The Allplay production here is solid; I loved the artwork provided by Nick Nazzaro on the player screens and the event cards, and the rulebook is exceptionally efficient, a testament to this and other Allplay rulesheets. I would only play it again at the max player count, on a much smaller table than my own, because players need to be able to huddle around the event cards. If you have the right group, pick this one up!