The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘X’.

X – The Quest for El Dorado: Heroes & HeXes eXpansion (2018)

Okay. So, here’s the thing. Dr Reiner Knizia, quite possibly the world’s most prolific and well respected board game designer, the man with over 800 designs to his name, the man who is currently celebrating his 40th publishing anniversary, the man to whom we’ve devoted an entire year and thousands of words to honouring, that Dr Reiner Knizia doesn’t have a single English language game beginning with the letter ‘X’. Or, at least not as far as we’re aware. We’ve spent a lot of time searching but it’s possible that an alternate title has slipped through the net somewhere.

Of course, we could have selected a game with a non-English title. We chose Jäger und Sammler for the Letter ‘J’ after all, and we even bent the rules to have Euphrat & Tigris for the Letter ‘E’. We could have picked ΧΑΜΕΝΕΣ ΠοΛιτΕΙΕΣ, which starts with a letter shaped like an ‘X’ and is the 2001 Greek release of Lost Cities. But that ‘X’ is actually a ‘Ch’ sound and we covered Lost Cities back with Keltis in the Letter ‘K’. Шерлок Холмс is the Russian name for 2013’s Sherlock Holmes but it doesn’t start with the ‘X’ and it’s another ‘ch’ sound (in the cyrillic script its called ‘Kha’).

Then there are games that feature an early ‘X’ sound. Games like Axio, Excape, Risk Express or HIT! Extreme (which we’ve also already covered in the Letters ‘I’, ‘E’, ‘A’ and ‘N’ respectively).

It might seem like we’re running out of options, this article about to expire, but worry not, because the dearth of games beginning with ‘X’ allows us to talk about Knizia’s various eXpansions. Expansions are an interesting area for Knizia. This is, after all, a man who has frequently said that “the art of game design is simplicity – not complexity!” and who has paraphrased Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s famous quote to say: “Many people think that a game is finished when there is nothing more to be added. I believe a game is finished when there is nothing more that can be taken away and still leave a good game”. Publisher Nick Murry (Bitewing Games) has even said that “even though publishers push him to include advanced variants or additional modules to a design, he’ll usually say that he prefers to play the simplest version of the game”.

Expansions are, even at their most basic level, a complete antithesis to Knizia’s design philosophy: by their very nature they add more to a game. It’s no surprise then that it took a while before he released his first expansion.

Indeed, it wasn’t until 16 years into his published game designer career that he released his first expansion: Lord of the Rings: Friends & Foes in 2001. Two further expansions and a promo followed for the game (see our discussion of the Letter ‘L’), proving that Knizia could design expansions if he wished to. Yet, expansions remain to this day an anomaly in his catalogue. Whilst BoardGameGeek curently lists 74 expansions, they’re only expanding 46 different games and around half are promos and collections of previous expansions. The total number of unique expansions (rather than promos) is actually 34 and those are only for 22 of his many games.

This numerical juggling perhaps unfairly minimises some promos. Given Knizia’s simplicity mantra, small additions can make a big difference: a promo such as the Black Butterflies promo for Butterfly Garden fundamentally changes how you approach the game.

Knizia clearly enjoys revisiting designs and expanding on ideas, but he does so more by redesigning and tweaking the original experience rather than simply supplementing it. For example, HIT! Extreme could have, in all probability, been an expansion for the original HIT! as, whilst it does tweak the card distributions, the main difference comes down to the addition of action cards. There’s a restless energy to Knizia’s design approach, he seems to prefer to always be moving forward rather than returning to earlier games. Knizia’s background in finance shows through in his approach to expansions as well – expansions rely on an existing audience whilst a new game can reach a wider market.

Yet despite this reluctance to expand, Knizia has proven adept in designing expansions. He can but generally chooses not to. Think of him as the tabletop equivalent of Stewart Lee, a stand up comedian who can write jokes but chooses not to. In fact, the parallels run further than that. Both men started their trade in the 1980s, came to prominence in the 1990s, appeared to dim a little after the turn of the century before coming back stronger than ever. There’s more: both are critical darlings in their fields, have loyal-to-the-point-of-cult followings, repeat and revisit favourite themes and ideas, create rigorously honed and some might say ‘dry’ works of art, and stick to a rigid ethos that makes their works distinctly theirs. Knizia, however, probably ranks higher than the 41st Best Board Game Designer Ever.

Despite his reluctance to design expansions, several games have seen multiple additions. The most expanded upon game in his entire catalogue is Blue Moon. A two-player duelling card game, 2004’s Blue Moon is Knizia’s answer to Collectable Card Games (CCG) such as Disney Lorcana and Magic: The Gathering (which he mistakenly advised designer Richard Garfield wouldn’t work when first shown a prototype). Featuring a starter set, deck-building and fixed content card expansions, what Knizia actually created was the first ever Living Card Game, a model that Fantasy Flight Games would hone with A Game of Thrones: The Card Game, The Lord of the Rings: The Card Game, Android: Netrunner, Arkham Horror: The Card Game and Marvel Champions among others.

Blue Moon received nine expansions and five promo cards in the two years following its release, and in 2014 all content was collected as Blue Moon Legends. In his review of Blue Moon Legends, Meeple Mountain’s K. David Ladage described it as “a nearly perfect game”.

Thanks largely to Lord of the Rings and Blue Moon, the 2000s saw a total of 15 Knizia expansions and 10 promos. You might have expected that trend to continue but Knizia’s diversification into wider markets meant that only 6 expansions and 5 promos were released in the 2010s. One of those – Carcassonne: The Castle – Falcon Expansion – was never even officially published (despite being in one of the most expanded game lines ever, it wasn’t published due to licensing changes) and was only released as a print-and-play on Knizia’s own website. The 2020s have seen a relative explosion in additional content for Knizia games, with 13 expansions and 20 promos released so far.

His more recent expansions include additions to newer designs, such as The Masterpieces for Mille Fiori, Full Moon for Witchstone and Nebular for Orbit. There are also the various reworked designs he’s released in the 2020s, such as Gazebo (2012’s Qin), SILOS (2008’s Municipium), Ichor (1993’s Tiku) and Merchants of Andromeda (2000’s Merchants of Amsterdam), which have all had small expansions released alongside them.

Perhaps most interestingly are the expansions for older games where the original game hasn’t changed (aside from updated art and production). Last year saw the release of Bazaar, the first expansion for 1998’s tile-laying classic Through the Desert, designed specifically for the 2024 Allplay edition of the original. Similarly, in 2023 25th Century Games released a new edition of 1999’s Ra, and this year they released a new expansion for the older statesman of auction games in the form of Traders. Both aim to stimulate renewed interest in the games from those already familiar with them, whilst enticing new players to discover their charms.

These patterns also reflect the wider industry trends. During Knizia’s 1990s heyday, expansions were far less common. The rise of the expansion in the 2000s coincided with Knizia releasing fewer hobby games, and therefore fewer games that would be suitable for expansions. Whether you feel that Knizia returned to the hobby or that the hobby remembered Knizia, his undeniable resurgence in the late 2010s and 2020s has seen a marked increase in expansion content. All those expansions and promos in the 2000s were only for 7 games, those in the 2010s were for just 9 games. In contrast, his 2020s expansion output to date covers a remarkable 31 games.

We’ve already discussed in this Knizia alphabet how 2017’s The Quest for El Dorado can be seen as the game that triggered the return/remembrance/resurgence and the reunion between Knizia and the hobby. Knizia himself doesn’t spend much time playing games by other designers. This isn’t because he’s not interested, but his high output doesn’t leave much time for playing games purely for pleasure. “When I design games, I feel a great sense of urgency,” he said to Shannon Appelcline at RPGnet, “I believe there are many great games in the universe for me to still discover and invent. As a consequence, most of my life is organized around exploring and developing new games. With all this playtesting, there is literally no time left to ‘play games’.”

Despite this, his playtesters tell him about the latest trends and hits, and a member of his playtesting group showed him the deckbuilding originator Dominion. “Dominion had created the deck building game [genre], it was a fantastic ground-breaking game,” he told Grace Tan at King and the Pawn, “but when I played it, I had problems understanding the game. It was very abstract.” This difficulty in understanding what to do and why prompted him to consider whether others would also struggle with it. “I was triggered by that because I wondered if it was possible to make deckbuilding more accessible to the general public,” he told Spellengek, “so I added the board to create a purpose for the deck you have.”

“I can’t always create a new trend,” he told Tan, “so I sometimes look at existing trends, and see if I can contribute more.” By adding the race and board, its easier to visualise what you are doing, making the game approachable for casual players as well as great for hobby gamers. In an interview with the World Series of Board Gaming he said that The Quest for El Dorado “is one example where I, being unable to be the designer of deckbuilding games, at least try to add something to it and not just run after the trend”.

The result is described as a ‘modern classic’ by Meeple Mountain’s Joseph Buszek. “One of the most accessible and fun deck-builders around,” he said in his review of The Quest for El Dorado, “it is in my top 5 from his immense catalog, and definitely his best original title in the last decade.” Buszek isn’t the only one to think so either. The game “put Reiner Knizia back on the map,” said Jon Purkis of Actualol, “for a lot of people that had got into gaming in the 2010s, there hadn’t been a big successful Reiner Knizia release, and this is the one where people were like ‘oh, who is this guy?’”

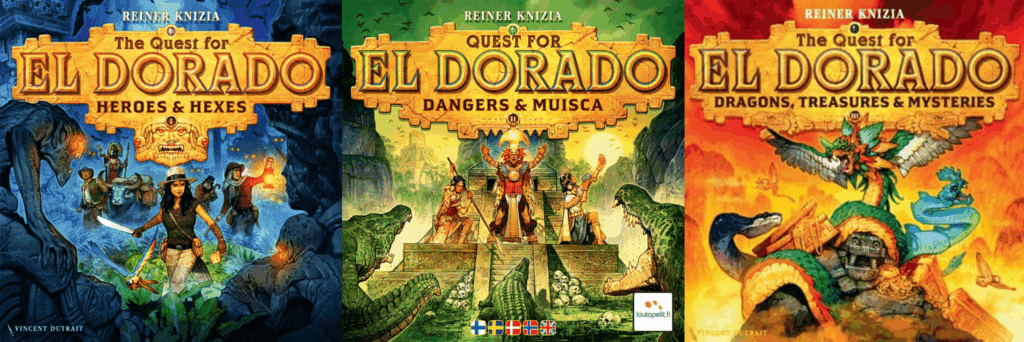

The success (and a nomination for the Spiel des Jahres Award) meant that the first expansion followed in 2018, along with a promo pack. Heroes & Hexes is the first of three large expansions for the game, with Dangers & Musica released in 2022 and Dragons, Treasures & Mysteries in 2023, both released alongside various promos. Sadly, due to licensing issues, there are now two main editions of The Quest for El Dorado and its expansions, with the first version with art by Frank Vohwinkel published by Ravensburger and the second version released in 2019 with art by Vincent Dutrait. It’s confusing and frustrating, the editions and expansions are not cross-compatible and expansions two and three were only ever released with the second edition. If you want to get into the weeds of it, you can read thoughts on the different editions by Knizia himself here and Dutrait here.

Heroes & Hexes includes cursed spaces on the new map tiles, more caves to explore, player powers in the form of familiars, and taverns where you can recruit hero cards to strengthen your deck. There’s no fixed consensus on which expansion is the best for the game, and Heroes & Hexes has had a mixed reception. Some love it, some less so:

“I think it’s a rock-solid expansion” Eric Yurko, What’s Eric Playing?

“For every good idea in this expansion, there are missteps.” Tahsin Shamma, Board Game Quest.

“It’s a box of bells and whistles that’s going to delight people who loved the original game. It delighted me and my friends, but I didn’t have to buy it. This box has quite a high price tag but it does not have a high quantity or exceptionally high quality of ideas.” Quintin Smith, Shut Up and Sit Down.

Regardless of the reviews, Heroes & Hexes represents an important turning point for Knizia, opening both his return to prominence and his gradual move towards more expansion content for his games. It’s for this reason that we’ve selected it as our entry for the Letter X.

–

And so we exit ‘X’. Were we excellent in our xenial examination and exploration of exciting expansions or should we be expelled and expunged from existence? What ‘X’ has the x-factor for you? Explain it to us in the comments below and explore the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!