The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘W’.

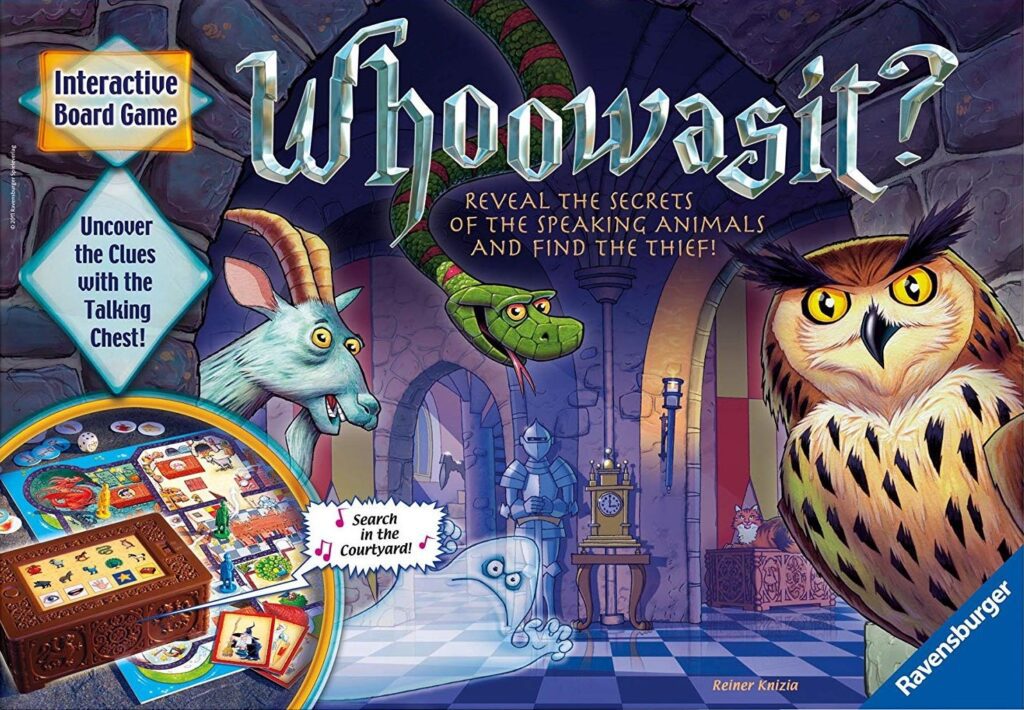

W – Whoowasit? (2007)

The thing about using the alphabet as a structure by which to reflect on Knizia’s career as a game designer is that it’s uneven. This list is lumpy because some letters contain many great games whilst other letters are a touch lacking. (And look out for how we tackle the Letter ‘X’ next time!)

There are plenty of ‘best of Knizia’ lists out there; we’ve read a lot of them. The problem with most lists is that the same titles come up again and again. Tigris & Euphrates, Ra, Modern Art, Through the Desert and so on. We’ve featured almost all of them and occasionally bent the rules to do so. They get mentioned so often when discussing Knizia because they deserve to get mentioned – many of them are masterpieces of design. We had to include them. (If you want lists that move beyond the common titles then consider Actualol’s 100 Reiner Knizia Board Game Ranked and Bitewing Games’ Ultimate Reiner Knizia Tier List that ranks 224 Knizia titles.)

But the alphabet has forced us to consider Knizia’s wider oeuvre, not just the games that hobbyists fawn over.

Which brings us to our pick for the Letter ‘W’: Whoowasit?, one of Knizia’s most successful games that almost never appears in ‘Best Of’ lists.

We’ve talked before about the different phases of Knizia’s career as a game designer. We’ve discussed his start in the 1980s, the big hits from his 90s hobbyist heyday, the popular narratives surrounding his latter career and his apparent comeback in the late 2010s. We’ve even touched on his targeting of the mass market.

But whilst we’ve eluded to it, we’ve not properly covered his move to also designing games for children.

As we’ve explored, Knizia’s first published game was released in 1985 and his first boxed game came out in 1990. Whilst many of his early games were family friendly (and most of his games are suitable for ages 10 years and up), we don’t actually know here at Meeple Mountain what Knizia’s first game targeting the kid’s market was. Attacke, published in 1993, is a contender, as are both Tor and Hungry from 1995, all of which are aimed at the 8 and up, but they’re very much games that adults can play without children as well. Casual games.

Really, you had to wait until the late nineties before Kniza started branching out and designing for younger kids. Games like KrimsKrams Flohmarkt-Spiel and Kurre aimed at kids four and up, and Bucket Brigade and It’s Mine! designed for children 7 and up, all of which were released in 1998.

Having left his day job in finance in 1997, Knizia’s output rapidly increased and diversified. He used his desire to design games for everyone (combined with his financial and business background) to move beyond the core hobby audience that had made his name, targeting children’s, family and mass market audiences. “The one thing you are fighting when you get more successful as a designer is that people try to put you in one box,” Knizia told Nick at Board Game Review, “I want to essentially get into all categories of non-digital gaming. I see that each game, each new segment I go into, enriches me.”

This interest in designing children’s games wasn’t just about reaching new markets or bringing games to more people; the process strengthened Knizia as a designer too. “I’ve put more focus on children’s games in recent years because I’ve found that they’re very interesting and very challenging,” he told Stephen Glenn of FunAgain back in 2002, “designing for children really widens your horizons… getting children’s reactions to games actually makes me learn some more fundamental things about games again. And those fundamentals are things that I can put back in the family strategy games, so it is something that enriches my whole approach to game design.”

The years between 1997 and 2000 saw an explosion of Knizia designs hitting every niche in sight. Hobby games such as Samurai, Tigris & Euphrates, Through the Desert, Ra, Lost Cities, Lord of the Rings and Schotten Totten. Casual family games like Circus Flohcati, Money!, Cat Blues, Excape and Relationship Tightrope. Younger fare like Hopp Hopp, Flinke Flitzer, Elephant’s Trunk and Leapin’ Lily Pads. The years surrounding the turn of the century were Knizia’s purple patch, an astonishingly prolific period where the designer was exploring new avenues whilst doubling down on what had brought him success.

Common opinion within the hobby is that Knizia turned too far towards the mass market as the 21st century wore on, only returning to hobby designs in the mid-to-late 2010s. We’ve argued that such a simple narrative isn’t necessarily accurate (see the Letter Q), but there’s no denying that from around 2005 onwards the relative proportion of family and children’s games among his output was far higher.

Which brings us to our pick for the Letter ‘W’: Whoowasit?, the only game that won Knizia the coveted Kinderspiel des Jahres in 2008, making Knizia the first person to win two Spiel des Jahres awards in the same year (the other being for Keltis). It’s a feat that has only been repeated once, in 2023 when Cyril Demaegd won two Special Prizes for Unlock! Game Adventures and Unlock! Kids: Detective Stories.

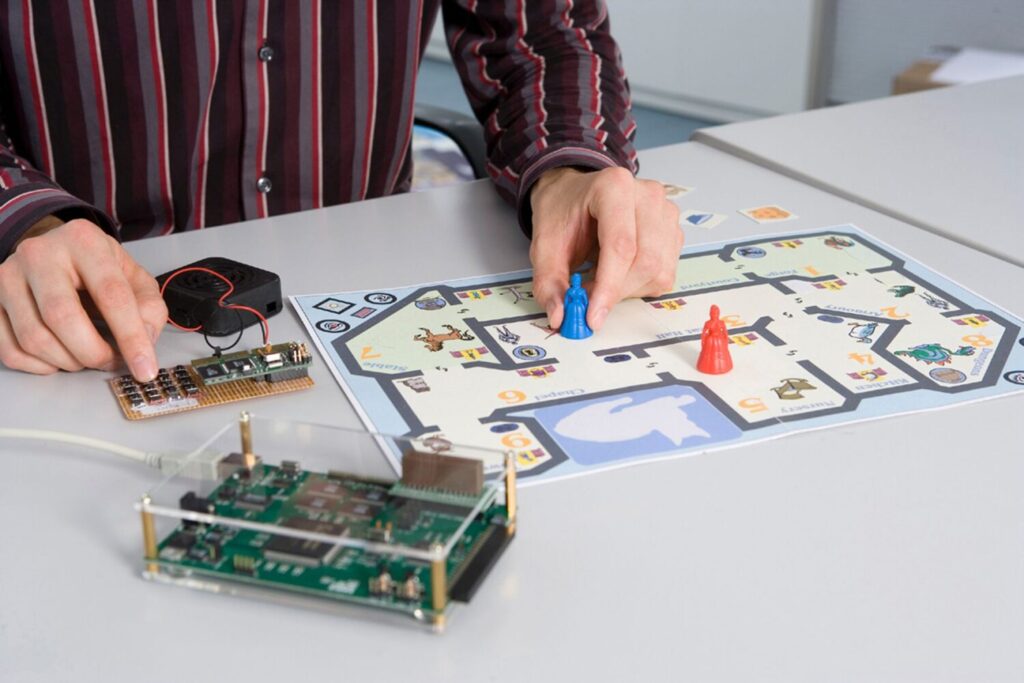

As the novelty of the new century waned, Knizia’s restless interest in game design saw him look at what technology could bring to the tabletop. “I’m absolutely convinced that soon we will see a new type of game that still gives us the atmosphere and the feel of classic, traditional boardgames, but that these games will be electronically supported,” he said in 2002 to Glenn. A year later, King Arthur, published by Ravensburger, was released. It was made possible by conductive ink that allows a small current to flow through your body when you touch different areas of the board. “New printing techniques connect the electronic unit with the standard gameboard,” he continued, “it looks like a normal boardgame, but the electronic is there and enriches the game. It is magic.”

The move to incorporate technology into tabletop games is, according to Knizia, a logical one. “We live in a world of electronics,” he told Leigh Alexander at Game Developer, “it’s just there, it gives a better user experience and better features, so why would that not naturally go into our games as well?” More hybrid games followed King Arthur including Die Insel (‘The Island’) in 2005 and Captain Black in 2015. Only last month at the 2025 Essen Spiel games fair Knizia announced the latest game in the series, Ventopia: Die fliegende Insel, whilst wearing welding goggles.

But Knizia hasn’t stopped with hybrid games. As technology changes, so do the opportunities for new designs. Where the original King Arthur used hardware in the game board itself, the 2014 update came with a bracket for a smartphone to be mounted above the board, keeping track of player moves and updating the game situation.

“If you are in a creative business, the best thing that can happen to you is change,” he told Alexander, “we just need to redirect ourselves, be open, and we can do new things.” Beyond electronic boards and conductive ink, he’s worked on mobile and console games, as well as designing games for physical technology such as the Dice+ (a bluetooth die that interacts with a tablet or smartphone) and the UniDice (an electronic die made out of 6 touch screens).

Interestingly, whilst he often experiments with new technologies, Ventopia appears to forego smartphones and apps and instead returns to an electronic board like many of his most successful hybrid designs.

Which brings us to our pick for the Letter ‘W’: Whoowasit?, originally published in 2007 as Wer War’s? Aimed at kids aged 6 and up, it’s a deduction game to find a stolen magical ring. Children don’t always play gently, so instead of embedding the electronics into the board using hardware and conductive ink, Whoowasit? uses a separate chest where you press buttons to tell the game’s brain where you are on the board and what you want to do.

On your turn you simply roll a die and move from room to room in the ‘wise king’s castle’, hoping to avoid the ghost and to find the culprit (and magical ring) before the evil wizard arrives. Once you’ve moved, you can search the room, talk to or feed the room’s animal or use a magical object. Figure out who the suspect is and get the right key, then you’ll be able to open the chest and claim the magic ring.

Whilst that describes the physical mechanics, it’s the interactive elements with the talking chest that makes Whoowasit? such a success. Animals talk and need to be bribed with food, magic occasionally backfires, characters fall through trapdoors, and the evil wizard and a good fairy occasionally make an appearance. “Having the talking treasure chest is like having your own dungeon master running the game,” says Ryan Billingsley at Dad Suggests, “The game is far more than just the innovation of the talking treasure chest – there is a lot of substance to the flash… the most important thing is that it simply makes our kids happy. It gives me great pleasure to see the kids excited about playing make-believe and rescuing the kingdom. Whoowasit? is the perfect way to bring a little magic to family game night.”

Many agree: Whoowasit? is one of Knizia’s most successful games and brands. “Wer War’s or Whowasit? won the game of the year and some other rewards,” Knizia said on the 5 Games for Doomsday podcast, “this is the one if you look at the financials and at the commercial side is the most successful one for us.”

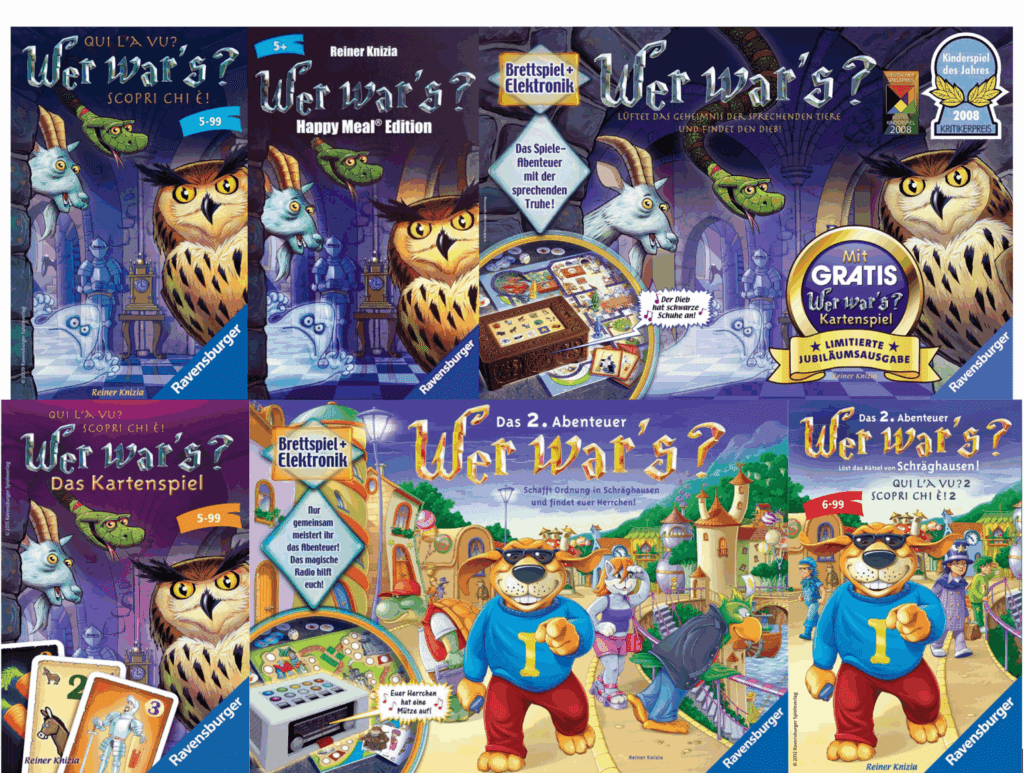

As with any success, more Wer war’s? followed. 2009 saw the release of a simplified memory game version with no electronics (Wer war’s?: Mitbringspiel). A sequel in 2010 featured an evil goblin who made children and farm animals forget everything (Wer war’s?: Löst das Rätsel von Schräghausen!). As with the original, it also had a stripped-down version in the form of 2012’s Wer war’s?: Das 2. Abenteuer – Mitbringspiel. A card game appeared in 2015: Wer war’s?: Das Kartenspiel. The only game in the series that isn’t cooperative, it’s actually a reimplementation of King Arthur: The Card Game, which itself is a card game version of Knizia’s original hybrid game King Arthur – everything is connected! The card game is also included in Ravensburger’s 10th anniversary jubilee edition of the game, released in 2018.

Perhaps the most curious Wer war’s? game is the Happy Meal version of Wer war’s?: Mitbringspiel, distributed at Austrian McDonald’s Austria in November 2015. It’s the dinky relative of this supersized family, demonstrating the success and reach of Knizia’s Whoowasit?, despite most hobby players having never heard of it.

Wandering the Wizard’s Work

Who would have worked out that ‘W’ would be wall-to-wall winners? Watch as we write about some worthy (w)runners up!

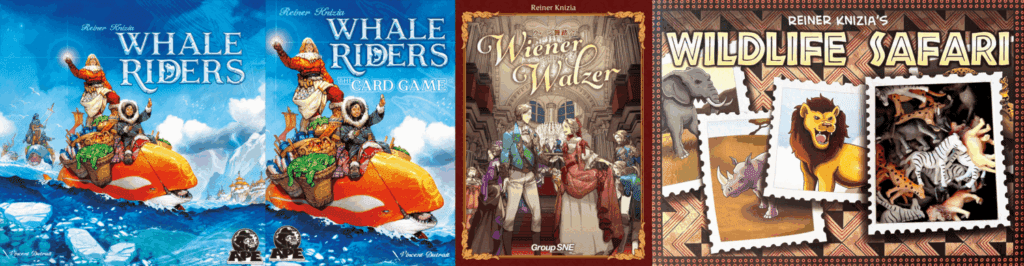

Whale Riders – The final collaboration before Knizia and publisher Grail Games parted ways for good (with the publisher’s claim of poor sales being countered by the designer’s claim of breach of contract). The split was a shame for Knizia fans, since it was a collaboration that resulted in ten gorgeous new and updated games, including Yellow & Yangtze, Circus Flohcati and the recent additions to the Medici family. In 2021’s Whale Riders, players travel by the titular whales, moving up and down an icy coast to collect resources and pearls. This original design was released with sister game Whale Riders: The Card Game, which is actually an updated version of 2000’s Trendy.

Wiener Walzer – Released in 2016, this game of Viennese Waltzing has yet to see an English-language edition, with original publisher Piatnik releasing it in French, German and Italian, and then publisher Group SNE releasing it in Japanese 6 years later. The essence of the game is placing male and female dancer tiles onto the floor. You want your dancers to pair off well, whilst also snaffling up sets of delicious canapes. It’s a rather delightful theme, and the gameplay is as smooth and elegant as the dance it’s based on.

Wildlife Safari – Botswana didn’t make the cut for the Letter B, so we’re featuring it here under its alternate title Wildlife Safari. Originally released in 1994 as Flinke Pinke, it’s a game that has seen multiple titles over the years, including Quandary and Loco!, with Wildlife Safari only appearing in 2014 from publisher Eagle-Gryphon Games. In all editions the gameplay is simple and satisfying. Players take turns playing a card in one of five suits and taking a marker representing one of those suits (in Wildlife Safari, the suits are African mammals). At the end of the game, the markers are worth the value of the final card played to each suit. This 30 year old design has just received another edition in the form of 25th Century Games’ Botswana, with stunning art by Weberson Santiago that’s almost worth the price of entry alone.

Winner’s Circle – Knizia’s greatest betting game? We featured Grand National Derby as our pick for the Letter G, but if you’d asked us to pick only one betting game then Winner’s Circle might have been it. Based on 1995’s Turf Horse Racing, the game was released in 2001 as Royal Turf and only later in 2006 gained the title by which it’s best known. Winner’s Circle sees players casting votes in three separate horse races, with the movement of the horses determined through simple roll-and-move. The challenge comes from deciding which horse to move with the result of the rolled die. “Many great racing/betting games have been released since the birth of Winner’s Circle,” says Nick Murray of Bitewing Games, “but this one consistently brings the fun like no other”.

Witchstone – 2021’s Witchstone is an unusual game in Knizia’s oeuvre, notable for being a co-design with Martino Chiacchiera, its one of his most complex games, features a ‘point salad’ approach to scoring and received a large expansion in 2023. Chiacchiera was originally inspired by Knizia’s Ingenious, and approached the veteran designer with his ideas. The pair used the hexagonal domino tiles and matching symbols of Ingenious to fuel Witchstone’s cauldron of actions that increase in power with the number of symbols matched. “Witchstone is fun,” says Meeple Mountain’s Justin Bell in his review of Witchstone, “it’s a point salad that is a slow starter with big moments down the stretch, featuring very accessible gameplay and solid, if not spectacular, design.”

Würfel Poker – Part of a series of nine tiny (just 11x11x4cm) travel games released between 2012 and 2019, all designed by Knizia and published by Süddeutsche Zeitung. Würfel Poker, released in 2015, is a shrunk-down dice version of Schotten Totten, with players using three dice to create pairs, straights and three-of-a-kinds to compete over three columns. Despite its diminutive size, it’s surprisingly compelling and there are some remarkably enjoyable ‘Play by Forum’ threads on BoardGameGeek from the years following its release. As the Süddeutsche Zeitung promotional material says, “It’s fun to play with the world of numbers and words!”

–

Well, ‘W’ is wrapped-up. What did you think? Were we well-accomplished and have we won your warm regards for our wisdom? Or was our wordsmithing wearisome and you think we’re woefully wretched and worryingly weak in our writing? What ‘W’ would have wiped your award board? Write your winners in the comments below and wander the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!