The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘L’.

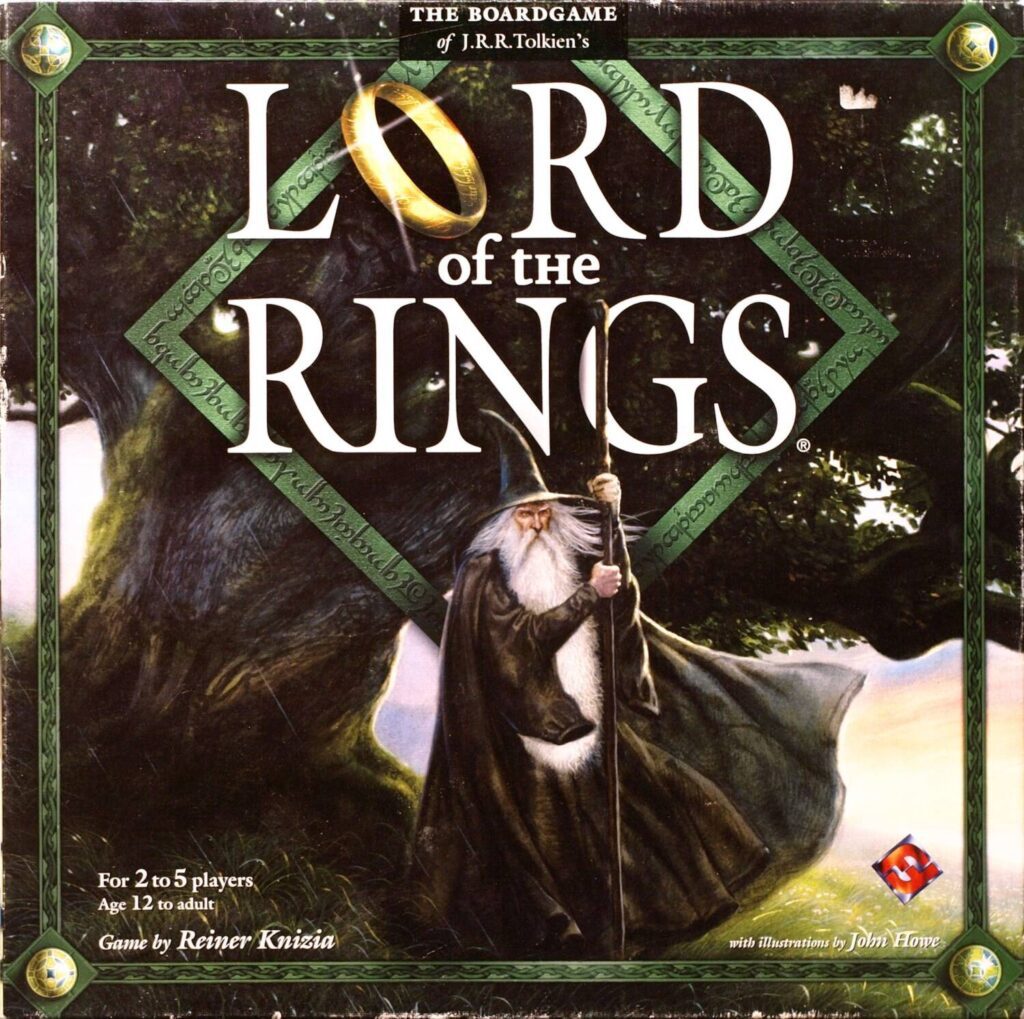

L – The Lord of the Rings (2000)

The Lord of the Rings is a landmark game in the cooperative genre.

There were, of course, cooperative board games before Knizia’s The Lord of the Rings. Even in 1903, Elizabeth Magie’s The Landlord’s Game, the game that became Monopoly, had an alternative cooperative ruleset known as the ‘Prosperity’ mode (coincidentally also the name of a 2013 Knizia release). And modern greats from before 2000 include 1982’s Sherlock Holmes Consulting Detective and 1987’s Arkham Horror.

But The Lord of the Rings showed the world that the European-style games that were sweeping the hobby at the turn of the millennium could also be cooperative. It paved the way for games such as Shadows Over Camelot in 2005 and Pandemic in 2008.

In The Lord of the Rings players take on the role of the four primary hobbit heroes from J.R.R.Tolkien’s books (and friend of Frodo Fredegar “Fatty” Bolger with 5 players). Over the course of the game the hobbits travel to destroy the one ring in the fires of Mount Doom, whilst doing their best to avoid being corrupted by the ring’s influence.

Illustrated by famed Tolkien artist, John Howe, it’s a game that has its fans in both the tabletop and Tolkien worlds. The Lord of the Rings is “a stellar game based on the books,” says Calisuri over at TheOneRing.net, “It takes such care and thought to actually destroy the ring that it never ceases to be a thrill when it happens.” Game critic Eric Twice agrees: arguing in 2021 that it “remains a great title… While most modern cooperative games follow the mold of Pandemic, The Lord of the Rings remains unique in its approach. It’s abstract, powerful, and thematic.”

Abstract. It’s a word bandied about a lot about Knizia’s The Lord of the Rings. Many feel that the gameplay is dry and mechanical, a process of moving along tracks and spending resources. They aren’t wrong, but here Knizia demonstrates the difference between abstracted gameplay and the themes abstraction can evoke.

The Lord of the Rings is “one of the most thematic games ever published not because it literally recounts Tolkien’s entire story as an abstraction,” says Michael Barnes of No High Scores, “but because it describes the literary themes that were important to the writer… It’s about themes such as self-sacrifice, overcoming impossible odds, finding the strength to endure corruption, friendship and other very human, very universal concepts.”

“Knizia’s adaptation of the literary classic is the only game I’ve played that truly recognizes this fact” says Twice, “[it’s] built on a theme of sacrifice. It is, after all, one of the central themes of the novel as well as the Catholicism which informed Tolkien’s work. We start at the strongest and only by giving away cards, time and other resources will we be able to reach the end. The game is based on expenses, not gains.”

For Knizia, remaining true to Tolkien’s work was crucial. “Even though I couldn’t cover the entire story line,” Knizia writes in his essay ‘The Design and Testing of the Board Game – Lord of the Rings’, “my aim was to stay within the spirit of the book so that the players would experience something similar to the readers of the book. These design goals would have many consequences for the game design.”

When asked about his design process, Knizia often talks about not using the same starting point for each design, forcing himself to innovate and move beyond his comfort zone. “I was very uncomfortable when I did The Lord of the Rings, because you want to be true to the story and the spirit of the book,” he said in an interview with Andrew Miller of And He Games, “it forced me to think in a new way, and therefore come up with something innovative.”

In the case of The Lord of the Rings, that meant acknowledging the themes of the story. “Pippin cannot ram his knife into Frodo’s back to get the ring,” he said in an interview with Funagain, “It’s just not true to the story… I had no other choice than to look at cooperative mechanisms to reflect the spirit of Tolkien”.

Whilst not unheard of, the idea of a cooperative game at the time was controversial. The key, Knizia found, was to build the evil of Sauron into the game. “The rules could not simply demand cooperative play,” he writes, “the game system had to intrinsically motivate this type of play. Therefore, I embedded the hobbits’ mutual foe, Sauron, into the game system itself.” We wonder what it says about Knizia when he has also said that the game is him playing against the players!

The process of working with a license and intellectual property forced Knizia to work in different ways as well. At the time he’d consciously decided to strategically pursue licences, in part to help improve the quality of game design in the licenced space. The vast Tolkien fan base meant that he wanted to get the game right. It took the full 18 months that he was provided with by Sophisticated Games, from discussions with Tolkien fan Dave Farquhar to designing what he terms a ‘scripted game system’ through to extensive playtesting and final refinements.

Working with a licence “sometimes takes the fun out of it”, Knizia has said, “I talk to a publisher and we agree on a big license and with it there comes a deadline. There comes a briefing with it… You’re much more restricted. But I find the license world fascinating and I really enjoy working in it!” Interestingly, it’s not an approach Knizia feels he would have succeeded at earlier in his career when he could simply put a design aside if it wasn’t working.

The game was a huge success. Released the year before the first of Peter Jackson’s critically acclaimed films (and featuring the work of Howe who was an art director on the films) it was perfectly placed to take advantage of the sudden wave of hobbit-fever that swept the world. The game has sold over a million copies and in 2001 it received a special award from the Spiel des Jahres for literature in games. As we saw when considering the Letter K, Knizia views awards as nice but far more important for how they raise general awareness games and help to grow the hobby. Even he, however, regards the award as “a very nice recognition”!

As a result of the game’s success and the lengthy design process where he overestimated the number of scenario boards the game would need, Knizia was quickly able to create expansions. Friends & Foes was released in 2001 and Sauron in 2002, with the final expansion, Battlefields, joining the fellowship in 2007. The expansions add more boards, characters, enemies and new mechanisms, such as manoeuvring armies in the field or one player taking on the role of Sauron.

Due to all his work on the game, Knizia found himself “even more impressed by Tolkien’s work” and of all the intellectual properties he’s worked with over the years, none have been more fruitful than Tolkien’s Middle Earth series. Between 2000 and 2013 he released a whopping 9 games and 3 expansions, coinciding with Peter Jackson’s two film trilogies, and even now in 2025 there’s a new game on the horizon (The Hobbit: There and Back Again).

Notable amongst his other Tolkien games is 2002’s Lord of the Rings: The Confrontation. It’s a very different take on the books, focussing directly on the battle between good and evil. Stratego-esque, it features asymmetrical victory conditions, unique character abilities and cards used to resolve combat. It’s also well regarded, receiving a Meeples Choice award in 2002 and Golden Geek nominations in both 2006 and 2007. In the same way that the original cooperative version received a 20th anniversary edition in 2020, The Confrontation will hopefully receive an updated ‘Ultimate Edition’ via crowdfunding in 2025 thanks to publishers Ghost Galaxy.

Whilst The Confrontation is excellent and we have a soft spot for the gem-based shenanigans of 2010’s The Hobbit, the original cooperative The Lord of the Rings is clearly the one game to rule them all, its effect on the hobby quietly wide-reaching. As Matt Montgomery says in his Don’t Eat The Meeples blog, “The Lord of the Rings gave shape to a genre” that Pandemic later defined. In a pleasingly circular (ring-like?) turn of events, this year, the quarter century anniversary of Knizia’s The Lord of the Rings, sees the release of the latest game in the Pandemic line: The Lord of the Rings: The Fate of the Fellowship.

Looking at Knizia’s Lovely Ludological Library!

Lords and Ladies, let us lecture you on more laudable leisure activities:

L.L.A.M.A. – We’ve already encountered the L.L.A.M.A. line when we covered the Letter D in our alphabet. This is the original camelid creation, however, a card-shedding, Spiel des Jahres-nominated alternative to UNO. “It’s light enough that you can play while chatting with your tablemates,” says Meeple Mountain founder Andy Matthews in his review of L.L.A.M.A., “but offers just enough decision space that you never feel as if you’re just laying down the next card in your hand.”

Longboard – Longboard feels like a relative to Lost Cities (see below), except with lots of card swapping and a surf setting. “It has all the trademarks of a solid Knizia filler,” says Andrew Lynch in his review of Longboard, “rules that can be explained in a handful of minutes, a simple but clever mechanic that’s highlighted by an uncluttered design, timing considerations that only become more obvious as you explore the game further, and a wonderfully interactive game space.”

Lost Cities – Like L.L.A.M.A. above, we’ve discussed Lost Cities already in our alphabet when exploring the Letter K. From humble beginnings, Lost Cities has risen to be one of Knizia’s most popular games, spawning a family of descendants that includes Spiel des Jahres winner Keltis. “It’s easy enough for a first time gamer to play,” says David McMillan in his review of Lost Cities, “and it’s challenging enough that even a seasoned veteran will stay intrigued.”

–

We’ve reached the end of the ‘L’ line! Did you find it laborious, lacking of learning, ledden and lamentable? Are we lightweight loons whom you loathe and long to lampoon and lambast? Or will you be lenient, lavishing our learnings and labours with love, and lauding us as legit legends for our ludography? What ‘L’ game is to your liking? Let us know in the comments below and check out the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!