This is the sixth (and for me, the last) volume of Perfected Game Mechanics (Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3, Volume 4, Volume 5), a series exploring games where, be they wonderful, amazing, inspiring, or even flawed in some ways, managed to utilize one particular mechanic with sheer perfection. That one mechanic is not going to be improved upon; there is nowhere “up” to go.

Note: with the exception of hexagon/square grid and deck construction, the images representing the mechanics are from BoardGameGeek.

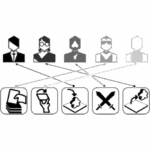

Action Drafting

Definition: Actions (or roles) are placed into a shared pool and players select which action (or role) they will be performing on their turn.

Twilight Imperium (any edition)

I believe the first game I ever played with this mechanic that impressed me was Twilight Imperium (back when I played either the 2nd or 3rd edition, my memory fails me as to which it was). Others that have come around and pulled me in to examine, dissect, and to get under the hood of the mechanic have been Puerto Rico and The White Castle. But nothing can compare to the agony of trying to get the proper action at the right time in Twilight Imperium (the actions are called Strategies within the game).

With five or more players, each may take one Strategy per round. With fewer, there is the option to allow each player to take two. Regardless, the choice can be agonizingly sweet! The first player to choose a Strategy is the player with the Speaker token. Gaining this token requires that you either take the Politics Strategy (and be 3rd in line to act) or to convince the player who took that Strategy to choose you. If you are not the Speaker, there is no guarantee that the Strategy you so desperately want this round will be available by the time your turn to choose comes around.

I cannot count the number of times I have started a new round of Twilight Imperium with Plan A dependent upon my taking a specific Strategy, only to see it taken. So I shift over to Plan B and watch that one go away, too. Then Plan C and Plan D do not fare any better. So Plan E it is… and you know what? Sometimes it turns out that with a little maneuvering and some wheeling and dealing, Plan E ends up better than my original ideas. More often than not, it means I am squirming until I can figure out how to adjust. But that is one of the amazing things about this behemoth: you are always adjusting if you want to have any chance of winning.

Despite being a game that takes a significant amount of time to set up, hours to play, and a significant amount of time to put away… despite being a giant box with a metric ton of components and a rulebook large enough to have had a hardcover release… despite being the kind of game that will cause all kinds of analysis paralysis… Twilight Imperium Third Edition spent nearly 12 years in the Top 50 Board Games of BoardGameGeek (143 months) reaching a peak of #22 with a rating of 7.7. As of this writing, Fourth Edition has spent over 7 years in the Top 50 (88 months – almost the entire time the game has been available) reaching a peak of #5 with a rating 8.2. Seems this game is going to stick around for a while.

This is Action Drafting perfection.

Connections

Definition: Each player is attempting to establish connections (e.g., paths) between disparate points or nodes on the board.

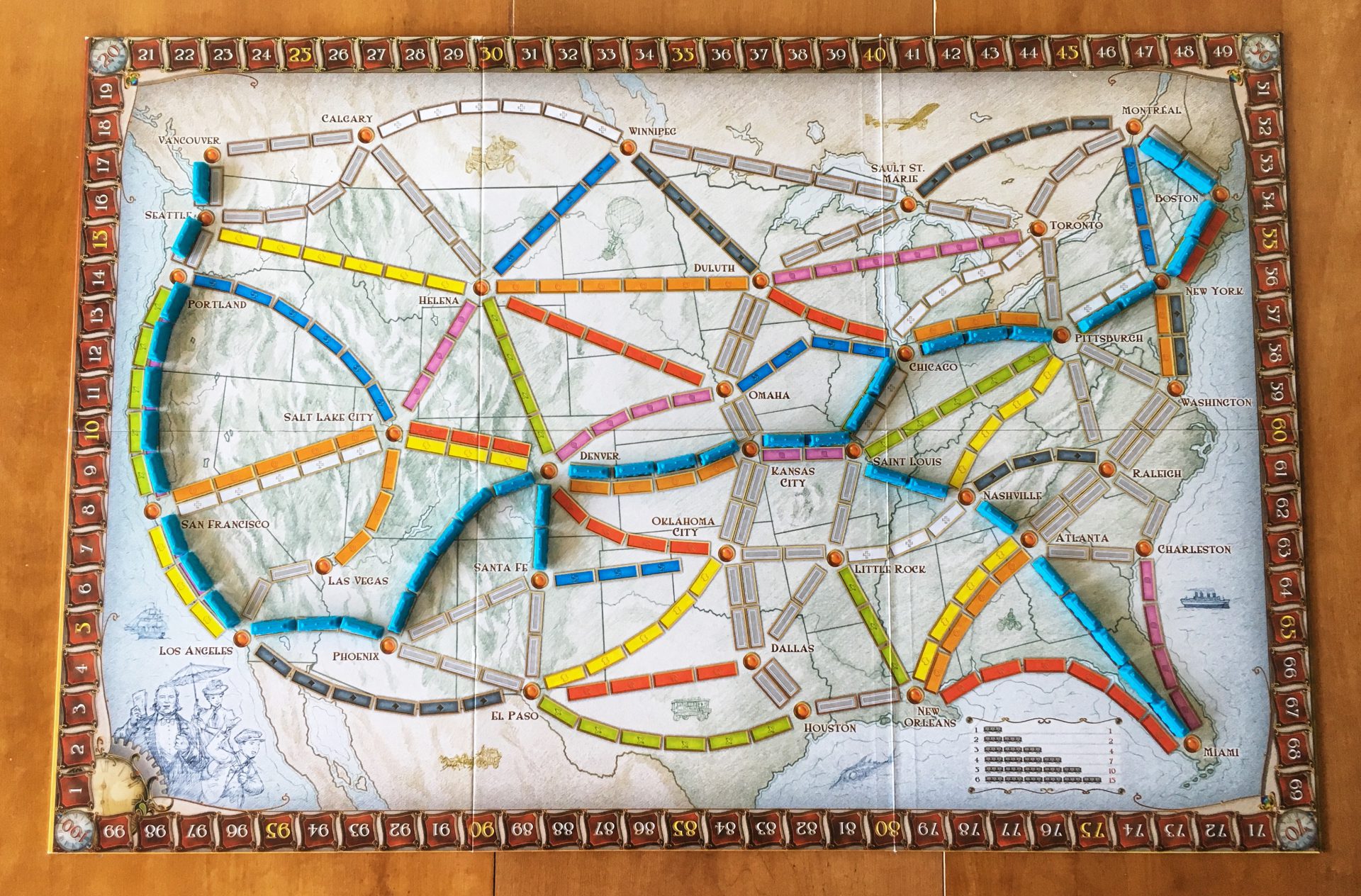

Ticket to Ride

Alan R. Moon released Ticket to Ride in 2004, over two decades ago. With colorful train cards and a board to match, this game was a hit. Unlike the deeper, heavier train games of yesteryear (yes, I can remember playing railroad games like Martial Rails with crayons), Mr. Moon managed to make a game that was approachable for younger players, while having depth enough for the older and wiser crowd. He managed to thread the needle between being a Strategy game and a Family Game.

And the game exploded! Between official expansions, smaller footprint spin-offs, and a plethora of fan expansions, there are over 170 ways to play this game. Each one keeps the core mechanic of being a set collection game with connections and designated goals (set by tickets listing two cities you need to create a route between) determining the scores. Yet each one also manages to tweak this, or add that, by way of making the map unique and interesting in its own right.

The Europe map adds in tunnels, ferries, and stations. The India map has scoring opportunities for creating multiple paths between ticket destinations. The Africa map has resources to gather. And so on. No matter your joy, there is a map for you. And those tickets I mentioned are dangerous! At the start of the game, you are dealt a few. Depending upon the board and the variants being used, there is a minimum number of them you need to keep. As you play, you can take a turn to draw some more, but each time you need to keep at least one. The catch to all of this? Each ticket is worth a number of points (generally between 5 and 20). Complete the route on the ticket, and you collect those points. Don’t complete the route, and you lose those points instead. Yea, a 20 point ticket has a 40 point swing between success and failure. It is rough.

If you want a game that will exercise your strategic thinking, play a game of the Mega variant (lots more tickets with some seriously long routes) on the American board with five players. It will not take long before you and two other players are vying for the same territory. This can be especially true if more than one of you has tickets going into Las Vegas.

This is Connections perfection.

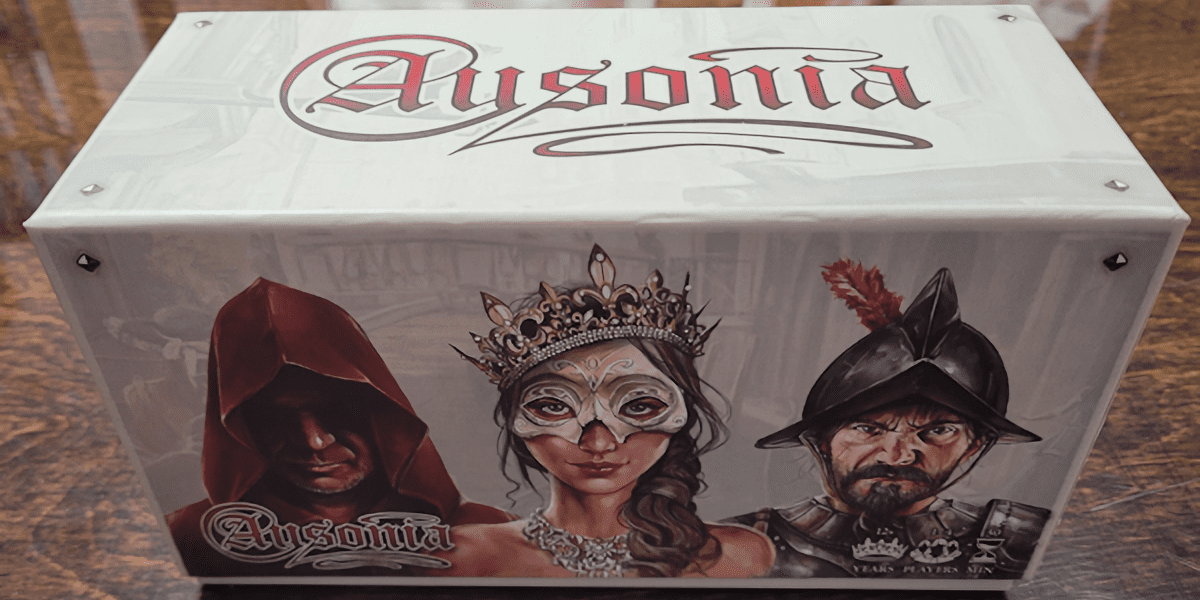

Deck Building

Definition: Each player starts with a deck that has some very basic cards. Each turn, the player draws a hand of those cards and uses them to purchase more advanced and powerful cards, or perhaps cards that are worth points, and adds them to their deck. Some cards may allow worthless or harmful cards to be put into an opponent’s deck. Others may allow cards to be removed.

Ausonia

Dominion pioneered this mechanic when Donald X. Vaccarino was playing in a draft tournament for Magic: The Gathering and thought it would be cool if a game was just the draft. The original set had 25 kingdom cards, of which a random selection of ten would form the market. Additionally, there were cards representing coins (i.e., copper, silver, and gold) as well as victory point cards (i.e., Estates, Dutchies, and Provinces). It is a wonderful game. The game, like any that invents a new mechanic and genre of board gaming, has always had its issues. Several other deck builders have come along in their attempt to improve upon the formula: since 2008, BoardGameGeek lists nearly 5,200 products using this mechanic, including Ascension, Concordia, Dune: Imperium, Great Western Trail, Thunderstone, Spirit Island, Star Realms, and many, many more. There are certainly plenty to choose from! Some of these use the deck building mechanic better than others.

Ausonia came out in 2021. The game looked at the way deck builders operated and managed to avoid the pitfalls of so many that came before: the biggest being the idea that an expansion would dilute the game of its original cards. Ausonia fixed this by having factions that are mixed together, but always in sets of five, making the draw pile 50 cards no matter what. If you want to play the original five factions, fine. If you want to play with an expansion faction, put it into the deck after you remove one of the others. This creates a different feel, opens up whole new synergies, and creates a game where this card or that is not lost in the shuffle of hundreds of cards. Add in the multiple ways to use each card, multiple ways to gain points, an ever shifting market, etc. and no two games of Ausonia are the same, despite never having a giant draw pile. The game always remains focused and fluid.

This is Deck Building perfection.

Deck Construction

Definition: Prior to play, each player must first construct a deck of cards, often with rules and limitations, which they will then use in the game.

Magic: The Gathering

Deck Construction originated with Magic: The Gathering. The tale goes that it all started with Mathematician Dr. Richard Garfield approached a small upstart company called Wizards of the Coast (perhaps you have heard of them) with a board game he had come up with called Robby Rally. The owner of the company, Peter Atkinson, indicated that he liked the game but Wizards was not yet in a position where the production of a full on board game was financially feasible. So he asked a question that launched an empire: “Do you have anything that uses fewer components?” As it turned out, Dr. Garfield did have something in mind.

The impact on the gaming scene cannot be overstated. In the period that followed the release of this amazing concept, so many attempts to get a piece of the action would come into play. TSR attempted a card based game in the same vein, Spellfire, which failed to get much traction (the truth is, you can still get it…). They would follow it up with a collectable dice game, Dragon Dice. Although Dragon Dice had a following, there were indications it was a bit rushed. For example, the rules were updated no less than twice in the first year as they attempted to rebalance things as players found some major exploits with a few of the mechanics (I am looking at you, Rending). Still, even after TSR dropped the game, others picked it up and continue its production to this day. It is a fun game.

Beyond TSR, there were other attempts to cash in. From collectable and living card games that dealt with starship and galactic conquest, to super heroics, to Wizards’ own attempt to bring the World of Darkness into this genre, there were many attempts to figure out what made this little game-that-could do what it did. It would be the Pokemon game that would eventually create a true competitor. Sure, others would come and go (most recently, Lorcana). Some would stick around for a while. But Magic: The Gathering has remained a cultural touch-point for over three decades and does not seem to be going anywhere anytime soon.

Oh, the game has flaws. That is for certain. Some have suggested that the fact that the original set of 300 or so cards with a few amazingly overpowered cards (the so-called Power Nine) may have something to do with it. Perhaps it was the ante concept, the idea that you had to risk ownership of any card you chose to use (which had a balancing effect on powerful cards), is what allowed it to capture so much attention. (Author’s note: once the cards approached maturity in collectable value, the ante mechanism had to go, since it caused the game to violate gambling laws in many communities.) Many of the attempts to copy the game’s success involved rules to defy the flaws in the game (e.g., mana screw).

There may one day come a game that would make us all remember with distant nostalgia the halcyon days when we played that quaint little game, Magic: The Gathering. But those days will likely be well after my days on this planet.

This is Deck Construction perfection.

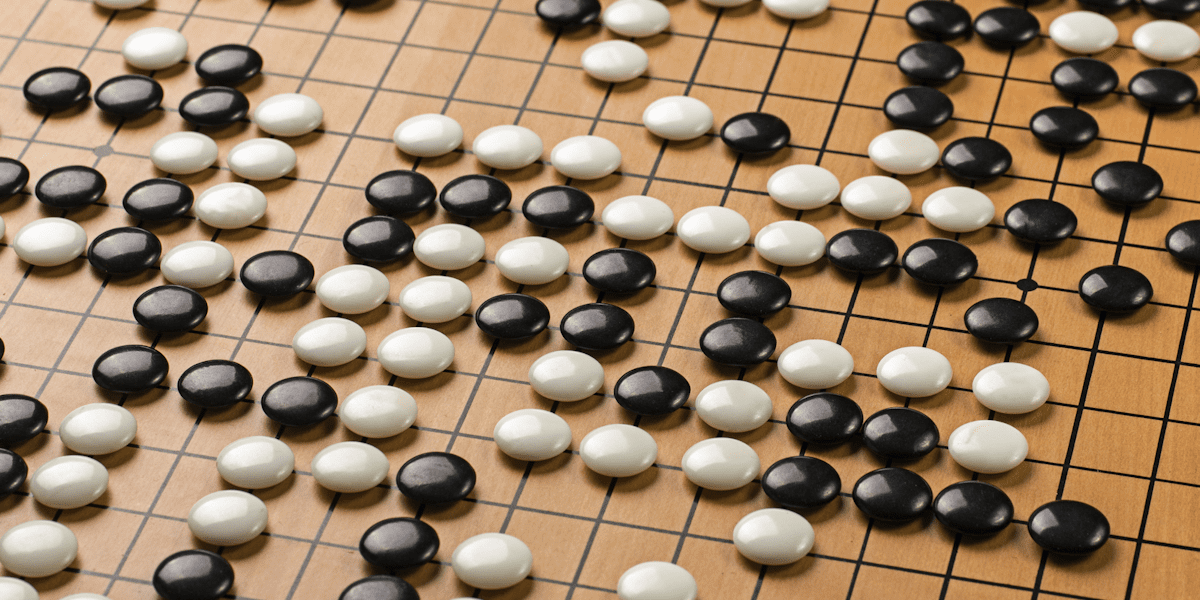

Enclosure

Definition: Players place and/or move components in an attempt to create and then gain control over areas of the game board.

Go

My first exposure to an Enclosure game was Cathedral. I met someone while I was in high School and attending a Chess tournament who had created a hand-made copy of the game. He claimed he had invented it. Sadly, I cannot say for sure whether or not I met Robert P. Moore that day. In my heart, I like to think so. Still, playing that game, getting a copy, and introducing it to some friends led me to my first exposure to Go.

With an origin somewhere around 2200 BCE, Go is one of the oldest games still being played today. The rules are simple, yet the intricacies of the strategies are so deep that computers were defeating Chess Grand Masters long before one came along that could best a Grand Master of Go. The story goes that when it happened, the Grand Master recognized that the computer was playing in an inhuman manner fairly early in the game and conceded. He asked what the computer was doing, and the programmer examined the logs to discover that it recognized that it was ahead by one, and stopped attempting to press its advantage; instead, it worked to maintain that one spot lead, playing in a way to deliberately maintain the status quo. This was later emulated in a Star Trek episode.

Go is a game that, like so many other games in this series, strips the play of anything other than its perfected mechanic. Go is enclosure. Nothing else. And it needs nothing else. Anyone who would attempt to claim that any modern game, even one as beautiful as Cathedral, could overtake Go as the perfection of this mechanic… well, you will have to wait about 4,200 years to see if any of those games are still played and discussed. Any time travelers are welcome to let me know what they have discovered.

This is Enclosure perfection.

A Quick Note…

Before we dive into what will be my final entry in this series (an entry that is not quite what any of the others happen to be), I wanted to talk about some of the mechanics that I have not included. There are a lot of interesting mechanics upon which board gaming and role-playing games have explored. Some are wonderful and I love them (as this list should signify); others tend to rub me the wrong way. So, it is my hope that someone on the team will take up Volume 7+ at some point and explore some of the mechanics they have enjoyed over the years.

We have a member who knows more about Trick Taking games than anyone I have ever met. My favorites (Tournament at Avalon + Tournament at Camalot) have probably not perfected this mechanic. Perhaps he will delve in and show us all what we might be missing.

We have a member who knows more about Abstract games than anyone I have ever met. Such games, in my experience, tend to delve into older, more established mechanics. My tastes have gone in that direction many times… but I am hoping they will delve into those mechanics and let us know where they shine.

I have enjoyed exploring the mechanics that stood out and reminded me why gaming is such a rich hobby. I hope you have enjoyed tagging along. But before we say good-bye, I do want to discuss two mechanics that are not always seen even as a mechanic:

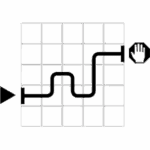

Hexagon Grid and Square Grid

Definition: the board is either divided into hexagonal spaces or into square spaces. These spaces regulate movement, production, or some other aspect of the game’s overall play.

Many, Many Games

There is a wonderful video online called Hexagons are the Bestagons. That video is funny, to be sure. But it also has a point to make. There are a lot of advantages to using hexagons over squares. But is it always an upgrade to do so?

No, not really.

Chess is a cornerstone of board gaming. It uses a simple 8×8 square grid. Each player has 16 pieces of six distinct types. There is a piece that has mastered orthogonal movement (i.e., the rook). There is a piece that has mastered diagonal movement (i.e., the bishop). There is a piece that combines the two (i.e., the queen). But this represents only half the pieces on the board. The game of Chess explores other options. The king is a very limited queen, but is the most important piece on the board. The pawns can move a single space straight forward as long as they are not capturing anything, but have to move a single space forward and diagonal to capture anything. Then there is the knight, a piece that moves between the lines so-to-speak in an “L” shape, resulting in the fact that nothing can block it. Chess took the Square Grid mechanic and used everything it could to create a game that some might call perfect. Even if you don’t, you have to admire the beauty and perfection of its use of this mechanic.

The game Queen’s Guard (a.k.a. Agon) hails back to 1842. Hexagons may have advantages in measuring distance moved and all that, but they were much more difficult to work with in the early days of board games. Still, by the time you reach the 1970s, the wargaming industry had fallen in love with these shapes. Hexagons are amazing in that they create a method of regulating movement without having to create special rules for diagonals (which are 1.41× the distances from center of square to center of square). Blast radii are much easier to visualize and rule. And so on.

Some modern games were the result of someone seeing a square gridded game and coming up with something that uses hexes instead (i.e., the story of the development of Hex by John Nash after an unfortunate game of Go; no idea how valid that tale is). There is a lot to be said for the humble hexagon (and the video above most certainly does). So yes, you do not always have to create a direct analog to the original when rethinking such things.

Many people (myself included) have attempted to improve upon Chess by reconfiguring it for hexagons. Some have been fine games, but they lack the elegance of the various moves on a square grid. Some games appear to be a rethinking of a mechanic on a square grid and applied to a hex grid (i.e., Tsuro to Butterfly Garden). Even when something new and beautiful is discovered, something is often lost in the translation. The key thing when using one or the other is to examine the game and its goals and ensure that the choice of grid serves the game organically.

Would the game Othello be better if it has been developed for a hexagon grid? Would any of the myriad space exploration and combat games be better if they have been developed for a square grid? There are multitudes of games which have embraced the square grid and used it beautifully. And the same can be said for hexagon grids. And so, with that in mind, I can honestly say that the number of games which represent Hexagon and Square Grid perfection are uncountable.

Final Thoughts

Games where each represents perfection in a specific mechanic (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda). Each has flaws, but they are eclipsed by the greatness within. Were I to give each game a full review, none would be rated below four stars. They are great games!

As I indicated above, this is the end of the line for me in this series. I have explored this topic throughout six volumes. As I indicated above, it is my hope that my colleagues at Meeple Mountain will delve into the 160 or so remaining mechanics listed on BoardGameGeek, or even re-explore a few of those I have already written about to provide an alternative perspective. We shall see if they want to swim in this particular pool.

What other games have managed to perfect a mechanic? What games have you played where you noticed a particular mechanic transcending its use elsewhere? Did the rest of the game measure up? Let us know in the comments!