This is the fourth volume of Perfected Game Mechanics (Volume 1, Volume 2, Volume 3), a series exploring games where, be they wonderful, amazing, inspiring, or even flawed in some ways, managed to utilize one particular mechanic with sheer perfection. That one mechanic is not going to be improved upon; there is nowhere “up” to go.

Note: with the exception of multi-use cards, the images representing the mechanics are from BoardGameGeek.

Cooperative Game

Definition: it is the players vs. the game. Either all of the players beat the game and win, or the game beats all of the players, and they all lose.

Mysterium Park

Cooperative games are an odd lot. They suffer from a lot of potential downfalls, from quarterbacking (where one player effectively directs the others in a solo affair) to games where it is not possible to win if the threats and problems come in certain specific oddball sequences (e.g., Castle Panic). Quarterbacking is likely the most difficult issue to overcome, since the quarterback will generally claim they are just trying to help. There are some games that do a decent job of overcoming this and the methods they use can be quite striking.

For example, in the Mysterium games (Mysterium and Mysterium Park) the issue is handled with a sense of supreme vagueness. You see, in this game, the goal is to provide clues using surrealist artwork, which means the clue giver (the ghost) must be providing clues to the other players (the psychic investigators) that speak to one person only as clues to be used with the cards only that person has. For example, a card may have an element that would work for the clue, but may be an element that would not be something the player would connect with. This means that anyone attempting to quarterback the game would be making things more difficult since the clue was not meant for them.

Mysterium is a great game, and from an artwork standpoint, it is the superior. However, Mysterium Park handles the turns, the flow, and the final reveal far, far better than its larger, older cousin. Both games have faults, but when it comes to handling the mechanic…

..this is cooperative perfection.

Mancala

Definition: players pick up tokens from a space. These are then placed, one at a time, into successive spaces around a track. Some spaces may have significance.

Mancala

The mancala mechanic is a beautiful one. BoardGameGeek lists 219 games that use it. Some of them I have played and I can recall the smile on my face when I recognized the mechanic within the game (e.g., Planes). Others, when I was reading up for this article, surprised me! I had played those games but did not recall the mechanic within them. I had to go back and look, and lo and behold! There they were (e.g., Istanbul, in the movement rules). A new smile.

The mechanic, when used properly, is beautiful because every single play alters the state of the board in subtle, potentially significant ways. Once a player picks up a set of pieces, every successive spot they pass through is changed, altering the possibilities for the next player (and the next one after that). Sometimes it makes an opponent’s play; other times it spoils everything they had intended. And as a player, you may or may not be aware of the consequences they are now suffering. If you spotted their move and made yours to counter it while gaining ground for yourself, you are well on your way to mastery.

I will not claim to have played dozens and dozens of mancala games. I have played a few, and in my experience the original is perfect. Mancala (or more properly, Kalah; technically, Kalah is the name of the game, mancala is the name of the mechanic) is a wonderful abstract game. It is the mancala mechanic stripped of all other considerations; laid bare as the whole of the game. It needs no theme. It needs no other mechanics to drive strategy or tactics. It is proof that this mechanic can stand on its own as a glorious example of game design.

This is mancala perfection.

Multi-Use Cards

Definition: cards have different values depending upon how they are oriented or where they are located. Each card may have multiple potential uses, but players are limited to using one when the card is played or obtained.

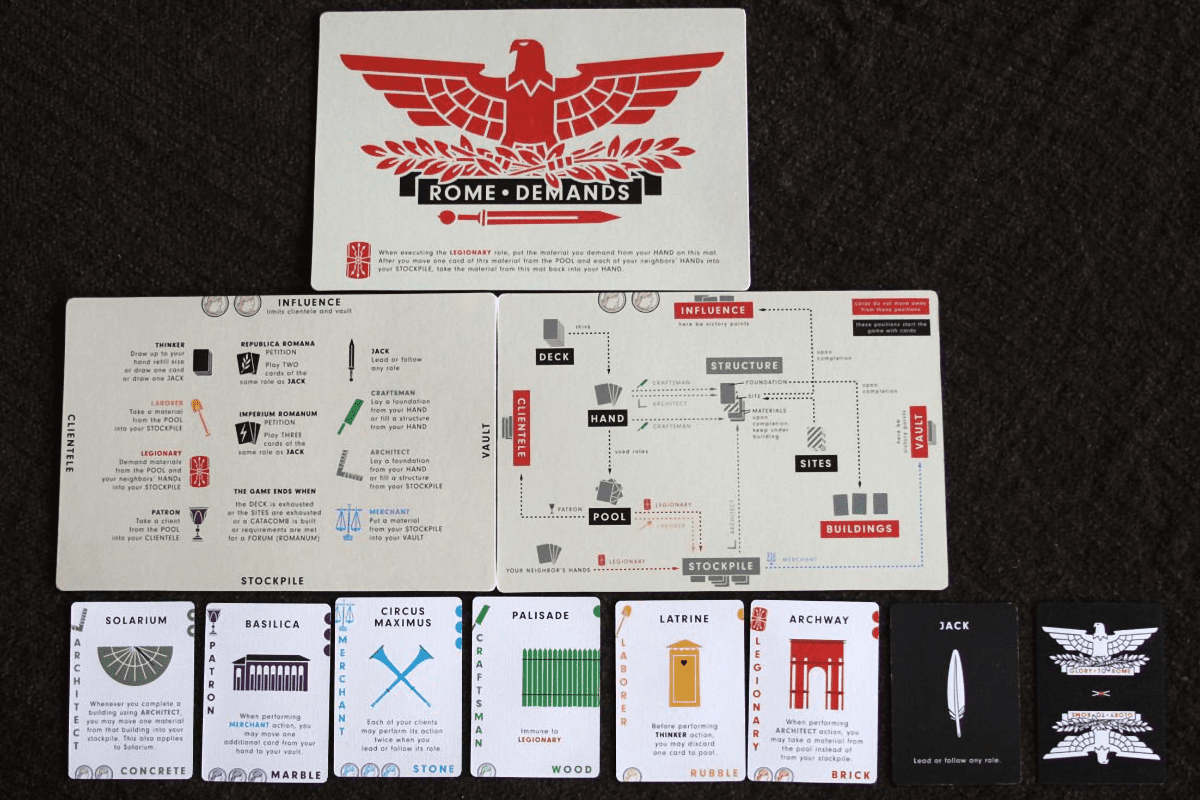

Glory to Rome

In the first volume of this series, I pointed out that Glory to Rome is a master class in using a single component in multiple ways. I meant it then. Here is that future volume where it shows up. My colleague, Justin Bell, wrote an article detailing the Top Six Games with Multi-Use Cards. I was not a member of the team when that one came out, but I was a huge fan of the site (I still am). I left a comment letting him know that he missed my favorite. He was gracious and thanked me for my suggestion. There is only one Justin Bell, and Meeple Mountain is lucky to have him.

Glory To Rome is one of those games that, once you play it a few times, assuming you can get your head wrapped around what designer Carl Chudyk is doing, you catch a glimpse of magnificence. The game is entirely card driven. You are trying to construct buildings to restore Rome after the great fire. Each card, depending upon where it is at the time can be:

- A building you might want to construct.

- A material you can use to construct a building.

- An amount of influence you can use within the game.

- A number of trade good points you can score.

- A specialist you can use to perform actions.

- A hireling you can hire to perform more powerful actions.

While any card is in your hand, it has the potential to be any of these. Place the card into play, and like a magic trick in quantum mechanics, probabilities collapse into a single truth: the card is now a building, or a material, or influence, or trade goods, or a specialist, or a hireling.

I will say that the game is tough to teach. If you want to learn, find someone who has played it many times. When you find that person and have taken the time, you will have discovered that…

…this is multi-use card perfection.

Player Elimination

Definition: a multiplayer game where players may be eliminated with the others continuing to play. The winner is often the last player remaining.

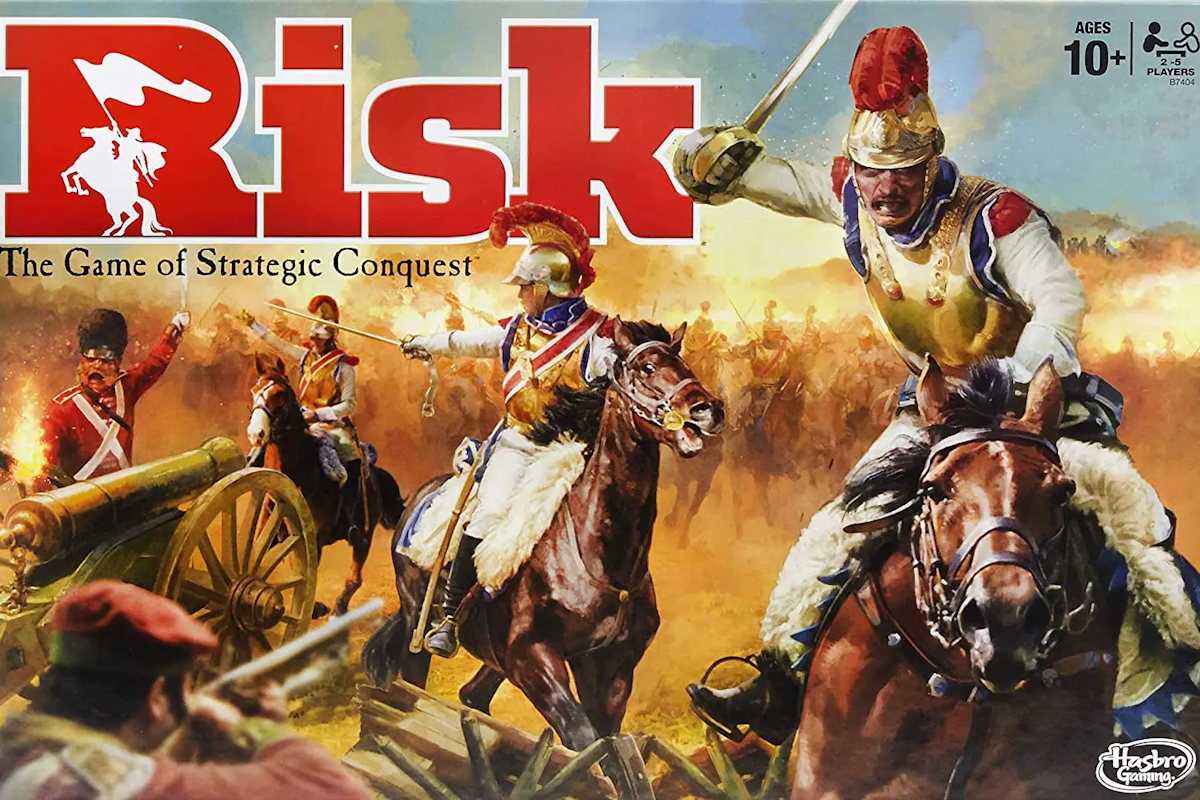

Risk

Player elimination is a staple of Ameritrash—those classic board games of old that, by modern standards, are not always very good. Everything from Monopoly to Axis and Allies to Cosmic Encounter falls into the Ameritrash bucket. That is to say, not everything in that bucket is actual trash. Heck, not everything in that bucket has player elimination. But one of the defining principles of the polar opposite of Ameritrash, Eurogames, is that there is no player elimination.

If you are going to have player elimination, one of the things you need, if you want to be considered a good game, is a palatable playing time. Monopoly, for example, tends to go on too long after the first person is gone. Some games do a great job of cutting the playtime down with this mechanic, such as Coup. And although Risk sticks around longer than Coup, it does so with style!

In Risk, the mitigation of the game’s length is in the bonus cards (i.e., the rapid escalation of their value), goal cards (i.e., in later printings, you can win without taking over the whole world), and the understanding of the odds (i.e., when someone has Asia, Europe, Australia, and Africa while three other players are splitting up North and South America… everyone knows the game is over). Risk is a quaint blips from an earlier time in board game design. It is a good (not great) game. But if you are into dice chuckers from a by-gone era that does not stay at the table too long…

…this is player elimination perfection.

Stock Holding

Definition: players invest into companies, commodities, countries, etc. Depending upon the relative strength of their holdings, they can earn points, or be granted privileges of ownership.

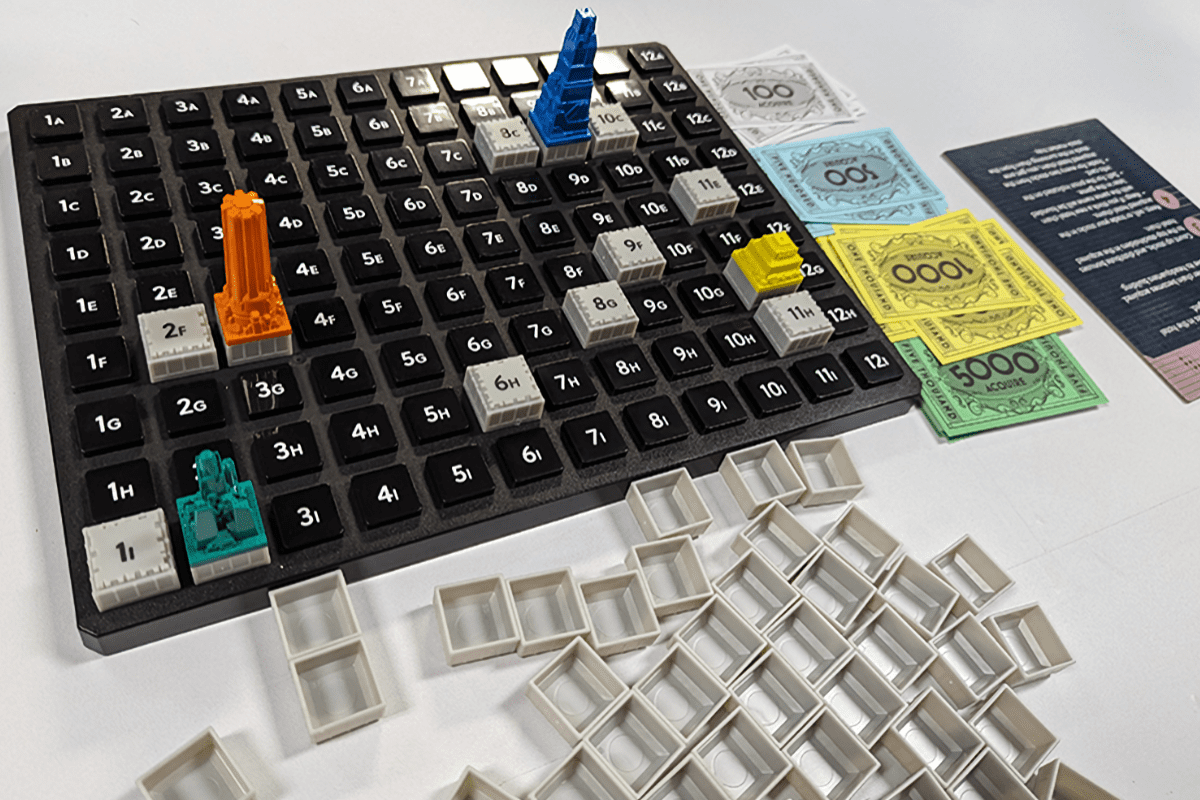

Acquire

BoardGameGeek lists 1,410 games that use the stock holding mechanic with release years ranging from 1878 (Monopolist) to three games coming out next year (Pivot, Wormhole: Dimensional Rift, and an expansion for Railways of the Lost Atlantis). All this is to say that this is a relatively popular mechanic in a world dominated by late stage capitalism. The fifth highest ranked game with this mechanic is Acquire (behind Maracaibo, Mombasa, 1830: Railways and Robber Barons, and Imperial). One might ask how a Sid Sackson game from 1964 remains popular and relevant for more than six decades.

The answer is simplicity.

The game is a simple grid of squares with spreadsheet-like addresses. These squares represent market share in the hotel business. Players take turns adding tiles from their hands to the grid location shown on the tile. This will grow this or that hotel chain. If this placement results in tiles being adjacent, then a new company is formed and the player gets one share of that company’s stock for free. After placement, players are offered the opportunity to purchase up to three shares of stock in any existing chain. The more hotels in the chain, the higher the price. Be careful, because each chain has a very limited number of shares.

Money gets tight! So eventually, you will want to play a tile that merges two or more chains into a single entity (or you will want to grow a chain into 11+ tiles to ensure it cannot be taken over). The chains that are dissolved pay out bonuses to those with the highest number of shares. Then those players can sell their shares, convert them to the resulting entity at 2:1, or save them and hope to start the chain back up again. The game is pure economics with a little luck of the draw. Strategy and thinking ahead are needed to rule the day. There is an updated version using hexagons called MegAcquire, and it is quite good. But the changes in the rules for stock acquisition and the overall flow of the game mean that the original remains king of the hill.

This is stock holding perfection.

Traitor Game

Definition: similar to the cooperative game above, except that one or more players is secretly working against the group. The object is for the main group to locate and stop/eliminate the traitor(s) before they can complete their betrayal.

The Resistance: Avalon

I read an article a long time ago with a title that was something akin to “The Most Important Game You Have Never Heard Of.” That article was talking about the small group that created the game Mafia, which has since become an industry of games attempting to one up the others in this particular realm: from Werewolf to Blood on the Clocktower. The idea of a group of people being slowly killed by someone within their midst (both with and without special powers sprinkled in) is not a game type that you, or anyone else, is unaware of these days.

These games all tend to be player elimination affairs as well. This is not good, given that someone is generally eliminated right at the start of the game. That poor soul now has to sit and watch as everyone else has fun. Some games will let the departed remain in a limited capacity, but this is not so much a cure as it is a band-aid.

The Resistance: Avalon solves this problem by removing player elimination. By looking at the game as a series of quests that need to be completed, players need to deduce who the traitor is (or traitors are). If they can keep the ne’er-do-wells out of the quests, they can complete them for the glory of the king. If they cannot, then the quests will fail and the enemies of all right minded people will usurp the throne.

This is traitor perfection.

Final Thoughts

Six games where each represents perfection in a specific mechanic (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda). Each has flaws, but they are eclipsed by the greatness within. Were I to give each game a full review, none would be rated below four stars. They are great games!

What other games have managed to perfect a mechanic? Meeple Mountain will delve into others in future articles. In the meantime, what games have you played where you noticed a particular mechanic transcending its use elsewhere? Did the rest of the game measure up? Let us know in the comments!