This is the second volume of Perfected Game Mechanics. This series looks at games where, be they wonderful, amazing, inspiring, or even flawed in some ways, managed to utilize one particular mechanic with sheer perfection. That one mechanic is not going to be improved upon; there is nowhere “up” to go.

Note: the images representing the mechanics are from BoardGameGeek.

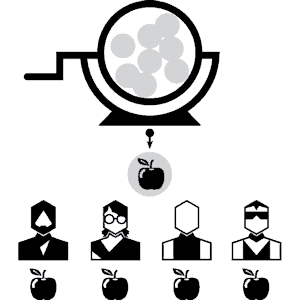

Bingo

Definition: items are selected at random; it is up to the players to best use the items on their individual player boards.

Welcome To…

Named for the game Bingo, this mechanic has been used in many games such as Cartographers, and My City. It is most certainly not a new mechanic (the game Bingo has been around since 1530). So how does one inject new life into this venerable mechanic? From left field, it would seem. When you first hear that Welcome To… is a game about assigning house numbers to three streets, it hits you with the level of excitement you might get from first viewing the box cover for Power Grid. If you take the time to play the game, you find that Welcome To… is a fantastic experience!

In the standard rules, each round, three pairs of cards are presented. Each pair has a house number (1 thru 15) and an action (build pool, hire temp workers, landscape, survey, invest, and «Bis»). Each player must select one of the three pairs and utilize them. With the house number, they will assign it to a house. The trick is that the numbers on each street must always be ascending from left to right. Then, on the house (or street, depending) the action is applied. This could mean building a pool (if the space is available for one), or shifting the house number by up to ±2, or putting up fences to define estates, and so on. Then a new set of three pairs are drawn and the game continues until those street plans are all completed or someone has no remaining unnumbered houses.

Based on that description, some might argue that Welcome To… only barely fits into the bingo mechanic. They are not wrong. In a typical Bingo game, there is one and only one option (e.g., B4) and everyone needs to follow suit. Welcome To… offers three options and allows each player to choose one. It fits into the mechanic and stretches it a bit. And that, I believe, is the secret sauce that makes this the best possible use of the bingo mechanic!

This is bingo perfection.

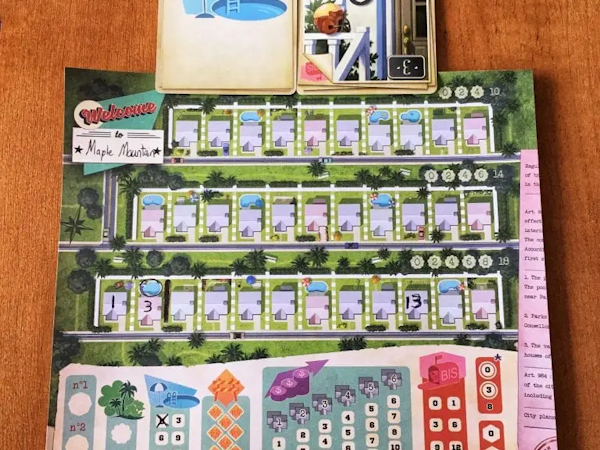

Push Your Luck

Definition: choose to either keep what you have gained so far, or risk it all to gain more. This is most well known as the mechanic used in Blackjack.

The Quacks of Quedlinburg

Push (or Press) Your Luck games have been around for a long, long time. BoardGameGeek lists more than 5,000 games using this mechanic. Many of these are gambling games (e.g., $ Fever), but a few are more modern designs (e.g., Trick Shot, Diamant). The mechanic has a simple limitation: one has to have a reasonable chance of advancing with a significant risk of backfire. If the odds are too favorable, then there is no excitement; if the odds are too risky, then there is no reason to risk anything. The games that can balance this will be successful.

No game tackles this better than The Quacks of Quedlinburg. In this game, you are an alchemist or a witch doctor or some other profession brewing up potions in a nine-day competition. With each day comes rewards allowing you to gather up more and more potent ingredients and put them into your bag where you are hoping to avoid drawing too many Cherry Bombs. Each ingredient has its own powers and benefits when they are added to the potion, the most basic is the numerical value of the ingredient which indicates how far your potion is pushed toward greater and greater potency. Cherry Bombs, for example, come in values of 1 to 3; you want to keep their total below 7 to avoid an explosion.

The game comes with many mechanisms: from the varied effects of each ingredient (making for a unique experience each time you play), to the beauty of the rat-tail catch-up mechanism (making a potion explosion something from which a witch can recover), to the flask which allows some mitigation of the risk (in a way that manages to encourage even more risk taking). Every aspect of the game cultivates a bag-management and risk-taking experience that always delivers a good time.

This is ‘push your luck’ perfection.

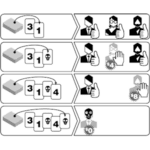

Roll (or Spin or Draw) and Move

Definition: roll the dice (or spin the spinner, or draw a card) and move your piece the resulting number of spaces.

Formula D (a.k.a., Formula Dè)

Roll and Move can be, arguably, the most boring of all mechanics. In classic games like Monopoly, The Game of Life, Candyland, and so on, the mechanic has a tendency to reduce player agency to the point of non-existence. In Candyland, for example, the ‘game’ has no thought involved. The player draws a card and moves accordingly. No choices, no thinking, no actual game is involved. Other games which center on this mechanic may have some choices along the way, but it is the weight of those choices and how they can impact gameplay that determine if the game is actually a game or just an activity.

One of the ways games will attempt to elevate this mechanic is to introduce multiple pawns for players to manage. In this way, the game appears to have more choices–after all, you could move this pawn five spaces or you could move that pawn five spaces. This is the entire Parcheesi family of games (e.g., Aggravation, Sorry, and a whole host of marble-based games from countries all over the world). Although this does offer a choice of sorts, the agency provided is mostly an illusion. So how do you add in agency, meaningful choices, and such into a game that centers on this rather limiting mechanic?

By making the limitations a part of the choices being made! Formula D is an F1 auto racing game with many published tracks to choose from. The game has many elements that make it a rip-roaring good time (I have friends back in Iowa who refer to this game as Cartwheeling Hulks of Flame). It is the way it handles the roll and move mechanic in the midst of its other mechanics (e.g., damage to the cars) that is nothing short of brilliant. Cars can be in different gears. Each gear is a different die, increasing in number of sides as you go up. The dice are not such that the 30-sided die has the numbers 1 thru 30 on it, but they do have an increasing range of numbers (e.g., first gear is a 4-sided die with a range of 1 to 2; fifth gear is a 20-sided die with a range of 11 to 20). This is added to a mechanic for the turns where you do not want to be going too fast when you get to them.

In other words, you need to weigh your current position on the track with the gears you could be in: your current gear, the next higher gear, or the next lower gear. If you need to drop down more than one gear, then things get a little dicey (sorry, I could not help myself). This is how you potentially cause damage to the brakes and engine, as well as use up precious fuel. Add to all of this car customizations, standard braking, weather effects, and so much more.

This is ‘roll and move’ perfection.

Spelling

Definition: arrange components to form letters and/or words.

Scrabble

As I was doing my research to write this article series, I was kind of surprised to learn that over 600 games use the spelling mechanic. I was certainly aware of a few: Boggle, Paperback, BuyWord, Jotto, and so on. But I had no idea how often and for how long this mechanic had been used as a game (as opposed to activities such as Crossword Puzzles). The earliest game with this mechanic that has a year listed for it on BoardGameGeek is 1874 (Logomachy); the highest ranked game with this mechanic is Paperback (from 2014). But for my money, nothing has done this mechanic better than Scrabble.

Scrabble is one of those games I feel no need to explain. It is nearly 80 years old and is ubiquitous in most parts of the world. Other games have come along trying to recapture what makes Scrabble so amazing. A few have come close. The online game Words with Friends, for example, is essentially a Scrabble clone. But even in this, they manage to muck it up. After playing many games during COVID, I learned to loathe the placement of the bonus spaces–they just do not make sense to me.

As indicated above, the spelling mechanic has been used in a wide variety of ways from using dice (Addiction, Boggle) to cards (Allwords, Word 4 Word). But the incorporation of the crossword-like placement of the letters to the scoring system (linked to letter rarity) based on an examination of every word used on the front page of the newspaper over several months down to the genius placement of the bonus spaces, Scrabble remains the king of spelling games. The underlying formula for how this game was designed and operates lays the groundwork for any and all non-English versions (of which there are plenty).

This is spelling perfection.

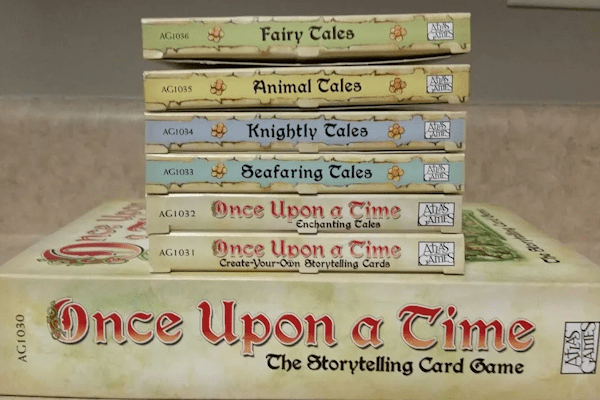

Storytelling

Definition: using game elements as prompts, the players use them to craft stories, either from whole cloth or by integrating them into the larger narrative of the game.

Once Upon a Time

I have to say, if I am being honest, there were years and years where I would not have looked at board games as having narrative weight. Stories were told in role-playing games like Dungeons & Dragons or Traveller, not board games like Chutes and Ladders. As I work through this series, I am discovering how myopic that view of board gaming is! From such classics as Clue (where the narrative is the gathering of clues to solve the murder mystery) to the campaign modes of games like Circus Maximus (where the narrative is the ups and downs of leading a team of charioteers though the racing season), there is narrative abound! Modern games have taken this further, thanks to Legacy games where the events of one playthrough live on into the next, creating a story that lasts for weeks, months, or years. Gloomhaven reigned supreme on BoardGameGeek for a long time based on the strength of the stories being told.

The problem with the narrative in most board games has to do with the limitations of outcome (e.g., you can win a game of Clue by outing yourself as the culprit… which you had no idea was the case when the game started) and theme (e.g., Gloomhaven is a great game, if you are a fan of combat oriented games). So there are a few games where the theme and the outcome become completely open ended: Rory’s Story Cubes is one such example. But nothing brings it all together into a better experience than Once Upon A Time.

Here you have a set of cards that include elements like various types of people (e.g., princess, knight), or creatures (e.g., dragon, giant) or items (e.g., crown, poison) or events and so on. Each player must attempt to incorporate the elements in their hand into the greater narrative without losing track of the story that came before. Mistakes or using an element in a way that is not significant will get you passed on and drawing more cards. If you can get all the elements in your hand into play and incorporate your final card into a satisfying conclusion, then you win. But in the end, the story told is more important than the game.

This is storytelling perfection.

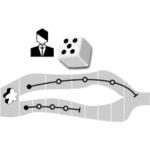

Tug of War

Definition: the score of the game is a differential. This can be a marker being moved back-and-forth along a track until it finally reaches some extreme, or a set of markers that are moved between players and a neutral location.

Blue Moon

There are only 180 games listed on BoardGameGeek that use this mechanic, and (as of this writing), Blue Moon is not one of them. This is an oversight that I have reported to the good people running the database, and I hope it will be corrected soon. For those unfamiliar with this mechanic and/or this game, this is the mechanic used in 7 Wonders Duel for military victories. Twilight Struggle is the highest rated game using this mechanic.

In Blue Moon, the mechanic uses three dragon figurines. These figurines start on the board in neutral territory. At the end of each round, the winner attracts one or more dragons. To do this, if they already have a dragon or all three are on the board, they move a dragon from the neutral zone into their play area. Otherwise, they move a dragon their opponent controls into the neutral zone. The game is won if a player has control over all three dragons. If the game ends without this being the case, then the player with dragons wins.

The way each round of the game is played is also, in some ways, a distorted reflection of the tug-of-war mechanic. Players play character cards from their hand, each time attempting to escalate the strength of the fight. Sometimes, that means trying to hold things still long enough to gain advantages in other ways (e.g., winning a fight with six or more cards in play allows you to attract an additional dragon, and so you do not want to jump too high too quickly). The tug-of-war aspect comes into this via the two elements within which you can be fighting – fire or earth. Mutant cards can be played which can move the fight to the opposing element, shifting the power dramatically. It is all very elegant, beautiful, and interesting. The game has many, many factions, each of which play differently. They each have their tricks, strengths, and weaknesses. But they are all playing the same (basic) game. This is a game that truly needed to get a lot more attention than it did when it was released.

This is ‘tug of war’ perfection.

A Quick Note

Tug of War is the 12th mechanic I have discussed in this series (13th if you count my example of Variable Player Powers). I struggled with this one. Although I do believe Blue Moon is the peak of the mechanic, there is a game that comes very, very close to being its equal. This indicates that there might be some ‘up’ for this mechanic in future game designs! That other game is Hidden Leaders.

Using two separate markers along the same track, the game is not one where the players are attempting to get this or that marker to an extreme, they are attempting to get them into a particular configuration. This results in my tagline: two armies, four factions, six leaders, one winner. This is a game that, with the right expansion, or the right designer being inspired after playing it, could cause the rule of Blue Moon to be cut short.

Final Thoughts

Six games where each represents perfection in a specific mechanic (IMVHO, YMMV, yadda yadda yadda). Each has flaws, but they are eclipsed by the greatness within. Were I to give each game a full review, none would be rated below four stars. They are great games!

What other games have managed to perfect a mechanic? Meeple Mountain will delve into others in future articles. In the meantime, what games have you played where you noticed a particular mechanic transcending its use elsewhere? Did the rest of the game measure up? Let us know in the comments!

Quacks is definitely a great choice for push your luck, I would put clank near the top too

Good call! Any other games have a perfected game mechanic in your opinion?