Here’s a quick recap of Let’s Build A Magic Deck – Part One:

Someone introduced me to Magic. Someone taught me how to play the wrong way. I sucked. Someone taught me the right rules and how to build a deck. I got good. I went broke. I got out. Then Commander arrived.

I suppose now is a good time to talk about Commander: what it is and what it means for me.

Part Two: What A Mess

Where I Extoll the Virtues of the Commander Format

As mentioned in the previous entry in this series, a standard Magic deck is composed of 60 cards—consisting of cards from very specific blocks—with no more than four copies of a single card in the deck. Each player begins a game with 20 hit points, and the players win by reducing their opponents’ health to 0. There’s nothing wrong with this mode of play. It’s the way I played Magic for decades. But, it’s costly since entire sets of cards are constantly being rotated out, and new sets are being rotated in. This means you have to constantly buy more cards if you want to compete.

The Commander format changes a lot of things. Firstly, in Commander, your deck is composed of 100 unique cards (minus basic lands, which you can have multiple copies of). Secondly, in Commander, except for a very small list of outright banned cards and cards from a couple of specific sets, you can use any cards you want from Magic’s storied history. New cards and old, all are welcome.

In Commander, each deck has a “commander” card assigned to it. Think of your commander as leading an army that’s composed of the other cards in your deck. Your commander must be a legendary creature (or planeswalker that has text that specifies it can be used as your commander).

As a quick aside, let’s define those two keywords: legendary and planeswalker.

The ‘legendary’ keyword is a specification that means only one copy of that particular creature can be in play under its owner’s control at a time and, if another copy of that creature would enter play, the first copy is sent to its owner’s graveyard.

Planeswalkers are a special type of card that were first introduced in the Lorwyn set in 2007. These cards are not creatures, but they are cast from your hand and live on your battlefield just as creatures do. Instead of having health and toughness, planeswalkers come into play with a number of loyalty counters on them. Each planewalker has abilities that can be used by either adding, or removing, these counters during your turn (and only when you could cast a sorcery, if you haven’t already added/removed loyalty counters yet during that turn). If a planeswalker’s loyalty counters are ever completely depleted, the planeswalker goes to its owner’s graveyard.

As an example, consider Jace Beleren, one of the earliest planeswalkers introduced to the game. With a casting cost of 1UU, he comes into play with three loyalty counters on him. By adding two, you can force every player to draw 2 cards. By subtracting one, you can force a specific player to draw a card (yourself included). And, by subtracting ten, you can force a player to put the top 20 cards of their library (a.k.a. their deck) directly into their graveyard.

Now that we’ve got that out of the way, where was I?

Oh, yes. Your commander.

Your commander lives outside of your deck in its own ‘Command zone’. It can be cast from the Command zone by paying its casting cost as normal. If your Commander ever dies, instead of going to your graveyard, you may put it back into the Command Zone, and the next time you cast it, it will cost two colorless mana more for each time it has been returned to the Command zone.

The colors of mana used to cast your commander are called its ‘color identity’. These colors dictate the colors of cards that can be used in your deck. So, if your commander costs red and white mana to cast, in addition to your lands, your deck can only contain red cards, white cards, or cards that are cast using colorless mana (such as artifacts).

In the Commander format, each player begins the game with 40 health. In addition to the two ways of winning I discussed in Part 1 (reducing your opponent’s health to zero or your opponent being forced to draw a card when there are no cards to draw), Commander introduces a third way to win. If your commander manages to do 21 points of combat damage (that is, damage dealt specifically through combat) to your opponent, they lose the game.

Before my wife bought me that Doctor Who Commander deck, I’d never seriously considered sitting down to play Magic ever again. Magic, as I have stated previously, is an absurdly expensive hobby. But, Commander has turned that on its head. I realized that, because Commander doesn’t care what cards you use, and because I am already sitting on a stockpile of old cards, I can create Commander decks and play them without ever spending another dollar on this game ever again. And the more that thought kept going through my head, the more determined I became to turn that thought experiment into reality.

It was time to dig out my old cards.

The Part Where I Forget Just How Many Old Cards I Have

What a mess. While it may not look like much from this photo, there’s probably something like 8,000+ cards here. It is apparent that I really cared about organization because some of these boxes are arranged by sets, divided by color, and alphabetized. It is just as apparent that I gave up at some point, or stopped caring altogether, because everything else is just tossed in here haphazardly: random boxes filled with random stuff, handfuls of loose cards, and Ziplock bags galore.

This doesn’t even include the three ring binders that I keep the sets that I collected in. Nor does it include my trade binder or the random deck boxes I have lying about. So, where to start? My trade binder seemed like my best bet. I had vague recollections of stuffing every rare* that I could find into it at some point in time. If I were going to find a commander to build a deck around, that’s probably where I’d find it.

*Magic cards come in one of four rarities. They are (in order from least rare to rarest): common, uncommon, rare, and mythic rare. Starting with the Arabian Nights set, cards began appearing with symbols representing the set from which they came. Beginning with Sixth Edition and moving forward, these symbols began appearing in different colors based on the card’s rarity. Black = common. Silver = uncommon. Gold = rare. Red = mythic rare.

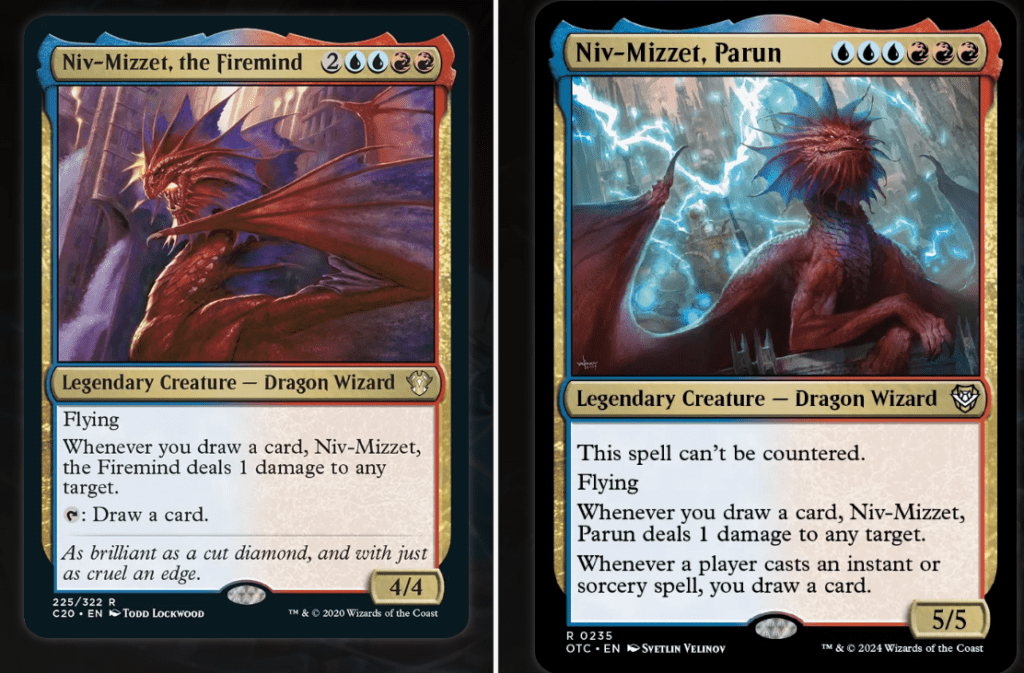

Almost immediately after opening my binder, I came across two cards that seemed like good commander material: Niv-Mizzet, Parun and Niv-Mizzet, The Firemind. Both of these seem like sound candidates, but Niv-Mizzet, Parun seems a bit better since it can’t be countered as it’s being brought into play. And, since its ability allowing me to draw cards can be triggered by any player, it has the potential to be triggered far more often than Niz-Mizzet, The Firemind.

So, blue and red. If I go with either of the Niv-Mizzets, those are going to be the colors I am working with. When I think about blue in Magic terms, I think about control, with all sorts of counterspells, card-drawing spells, and spells that help me take control of my opponent’s things. I think about things living in the water and things flying through the air. Blue is the color of water, and the pacing of a blue deck is generally slow, wearing down your opponent through attrition, like a river carving a canyon into the landscape.

Red is the color of fire and chaos. Famous for its goblins, dragons, and other creatures born of flame, it’s also well known for its deep catalogue of direct damage spells. Red is an aggressive color, focused on fiery destruction. There’s nothing subtle about playing red.

I can already tell from either of the Niv-Mizzets that card drawing is going to be a major focus for my deck, since that’s what triggers Niv-Mizzet’s damage dealing ability. The more often I draw cards, the more often I hurt my opponents. I also have a feeling that other players are going to do everything in their power to keep me from drawing cards or even getting Niv-Mizzet out of my command zone. This means I am also going to need a healthy amount of countermagic to thwart those efforts. So, I think my blue focus is going to be on these two elements: card drawing and countermagic with a sprinkling of big, stompy flying creatures thrown in for good measure.

The Part Where We Talk About Timing

It occurs to me that some of you reading this may not know what the term ‘countermagic’ means, and it bears defining the term to help you better understand how the game is played. I’ve glossed over a few details here and there in an effort to keep the narrative flowing, so I’ll try to keep this terse so that I don’t bog you down with detail. Countermagic is defined as ‘any spell or effect designed to remove another spell or effect from the stack’, another term that requires explanation. I’m going to try my best to explain it here, but I will admit, it can be very confusing.

When you attempt to cast a spell from your hand, or use a card’s effect, that attempt goes into an imaginary limbo space called ‘the stack’. Imagine the stack as a physical stack of cards, and each card has your intention written upon it. If that intention is allowed to resolve without any interruption, then your intention comes to fruition. However, if an opponent wishes to do something to interrupt your intention, then (after paying any costs for doing so) their intention is placed onto the stack on top of yours. This intention may be completely unrelated to yours, or it may be something specifically added to mess with your intention. Once players have stopped adding things to the stack, the stack resolves, and it resolves from the top down (last in, first out). Depending on the results, the original intention will either succeed or fail. To better demonstrate this, let’s consider an example using these three cards: Wren’s Run Packmaster, Unsummon, and Counterspell. I am playing a blue/green deck and my opponent, Bob, is playing blue.

Wren’s Run Packmaster costs 3G. As an added cost for summoning this creature I must “Champion an Elf” (which is described on the card). For the sake of this example, we’ll imagine that I only have a single elf in play, and I decide to use this single elf to satisfy the “Champion an Elf” portion of Wren’s Run Packmaster’s cost.

Bob doesn’t want Wren’s Run Packmaster to hit the table, as he’s not fond of its ability to start producing a bunch of Wolf creature tokens that have deathtouch (a keyword which means that anything damaged by this creature dies, regardless of how much damage it sustained). So, he attempts to foil my plans by tapping U and casting Unsummon to return my single elf to my hand. If there’s no elf for me to use to satisfy the “Champion an Elf” portion of Wren’s Run Packmaster’s cost, then Wren’s Run Packmaster will fail to cast (a.k.a. fizzle).

I’m not of the same mindset as Bob. I think having Wren’s Run Packmaster in play would be amazing, so I tap UU to cast Counterspell, targeting his Unsummon spell. Bob decides not to play anything else. At this point, there are three spells on the stack. From top down: Counterspell, Unsummon, and Wren’s Run Packmaster.

The stack resolves in this order:

My Counterspell counters his Unsummon, removing it from the stack. Wren’s Run Packmaster resolves, removing my single elf from play. Because she has summoning sickness, she cannot attack this turn. However, since Wren’s Run Packmaster’s activated ability doesn’t have the ‘tap’ symbol, if I had the mana, I could immediately use its ability to generate Wolf creatures.

It’s a good thing I had that Counterspell in my hand and the mana to cast it! Otherwise, my single elf would have been returned to my hand by Bob’s Unsummon spell, and Wren’s Run Packmaster would have fizzled, sending it to my graveyard. And, I’d be out of the mana that I spent attempting to cast it.

Anyway, I apologize for going off topic, but I thought that understanding the way the stack works is something you should know. Thanks for sticking with me. Let’s get back to building the deck now, shall we?

The Part Where My Mind Starts Spinning

While reading up on Niz-Mizzet, I became aware of a blue spell called “Curiosity” which is a creature enchantment that allows me to draw a card whenever the creature it’s enchanting deals damage to an opponent. Paired with Niv-Mizzet, this would allow me to do an infinite amount of damage to my opponent. I’d draw a card, Niv-Mizzet would deal damage to my opponent, and this would allow me to draw a card (because of Curiosity), which would cause Niv-Mizzet to deal damage to my opponent, rinse and repeat, until I decide to stop the loop.

Curiosity has seen a lot of reprints over the years, but they’ve all come about since I stopped playing the game. However, this card originally came out in the Exodus set during the Tempest block, and this was a time when I was heavily invested in the game. So, there’s a decent chance that I might have a copy somewhere. Fingers crossed.

I’m thinking that my red color focus is going to be on direct damage spells and goblins. I’ve got an old goblin deck somewhere that I can pirate, and one of my very first Magic decks was a mono-red direct damage deck. I reckon that I’m going to need these spells in order to clear the table of any creatures my opponent may get into play, as well as to chip away at their life total in a way that can’t be blocked by anything other than countermagic.

Before I can start putting this deck together, though, I’ve got to address this storage situation. My library of cards is in a state of chaos. There’s no rhyme or reason to any of this, and that’s got to change if I want this deck-building experiment to be a success.

It’s time to get organized.