The subject of today’s Step Ladder is Catan.

In an article I wrote a few years ago for International Tabletop Day I talked about how I was introduced to Catan (or The Settlers of Catan as it was known back then). What I didn’t discuss was why I liked it so much.

What initially drew me to the game was that it was like nothing I’d ever encountered before in a board game. It has trading and negotiation, a modular board design, resource management and building, the ability to be expanded upon, and a point salad mechanism. Maybe none of those elements was brand new to game design, but they were brand new to me and they had the benefit of being presented to me in one elegant package.

This Step Ladder is a little different than others that have come before it. There are a lot of reasons to like a game such as Catan and I feel it would be doing a disservice to what is arguably one of the most influential games in board gaming history to simply try to associate it with only one or two other games. So, this Step Ladder article is actually a series of different Step Ladders with one thing in common: Catan.

Maybe those aspects that drew me to Catan are the same ones that sing to you as well or maybe there are just one or two things about it that you like in particular. Regardless, my hope is that if Catan is your only foray into the vast world of hobby board gaming, hopefully some of the other games below will delight you as much or even moreso.

NOTE: this Step Ladder article assumes that if you’re reading this, you already know how to play Catan. If you haven’t actually played the game yet, then I recommend checking out Tom’s very thorough walk through of the game in his Games We Love article!

Negotiation: Bohnanza -> Catan -> Rising Sun

Bohnanza

Uwe Rosenberg is well known for his heavy, thinky big box games like Agricola and A Feast For Odin, but one of his earliest forays into game design was this little game about bean farming.

In Bohnanza, the players are bean farmers trying to sow and reap the biggest bean crops for the most reward. In each player’s hand are an assortment of cards that feature the image of one of several types of different beans on the front of the card – stink beans, green beans, and chili beans are some examples. On a player’s turn, they must plant the first bean card from their hand into one of their two fields.

There are two catches to this planting process: each field can only contain one single type of bean and no player can ever change the order of the cards that they hold in their hands. If you are forced to plant a new type of bean into a field that is already occupied by a different type, then you must first harvest that field to make room. The amount of money you earn for doing so depends entirely upon how many beans are in that field and which type of beans they are. This can score you 0 points just as easily as it can score you a boat load.

And this is where the negotiation enters into the game. After a player plays their first bean, they then draw the top two cards off of the deck and place them face up onto the table. They may choose to keep and plant these cards if they so desire or they may decide to try trading them for beans that are more beneficial to them. They can even use this opportunity to try to trade off unwanted cards from their hand. It is this negotiation aspect that makes Bohnanza such a fun game and is no doubt part of the reason that Bohnanza has enjoyed the success that it has over the years.

The next game on this Stepladder is the hero of this piece: Catan. The reason it sits one rung above is because in terms of complexity, Bohnanza’s a much easier game to wrap your head around.

Catan

Designed by Klaus Teuber, one of the most thrilling aspects of Catan is the trading and negotiation that goes on in the game as players try to find optimal ways to turn sub-optimal card trades to their advantage. Since you will always know which resource cards your opponents are holding (theoretically) you can deduce what they’re needing in order to improve their own lot and you’re able to decide just what you’re willing to give up to them in return for improving your own position (and sometimes you just need to get rid of cards to avoid getting robbed in case someone rolls a ‘7’).

Yes, there’s no denying that negotiation is at the heart of Catan. In fact, it’s quite possibly the most important aspect of the game.

The next game on this Step Ladder takes negotiating and deal making to an entirely different level.

Rising Sun

At its core, Rising Sun, Eric Lang’s brainchild, is an area control game where feudo-fantastical military units and monsters of Japan are used to score points as players needle one another to maintain their grip on the land. Players do this through an alliance system where almost everything is negotiable and hidden tactics are a staple part of play. At the beginning of each round all players take part in a “Tea Ceremony.” Essentially this gives players the opportunity to decide if they want to ally with another player or fend for themselves; having an ally gives you extra bonuses when actions are taken during the game, but playing solo gives much more flexibility to take aggressive actions without fear of repercussion.

Players are allowed to negotiate almost anything in the game. They can make promises to move in or out of locations, they can give money to players to coerce a favorable action, and allies often negotiate with one another on which actions to take. Rising Sun can test the subtleties of negotiation as nothing is binding and downfall is just one Betrayal action away.

If you’d like to dig deeper into the way this game is played, read our full review of Rising Sun.

Modular Board: Heroscape -> Catan -> The Oracle of Delphi

Heroscape

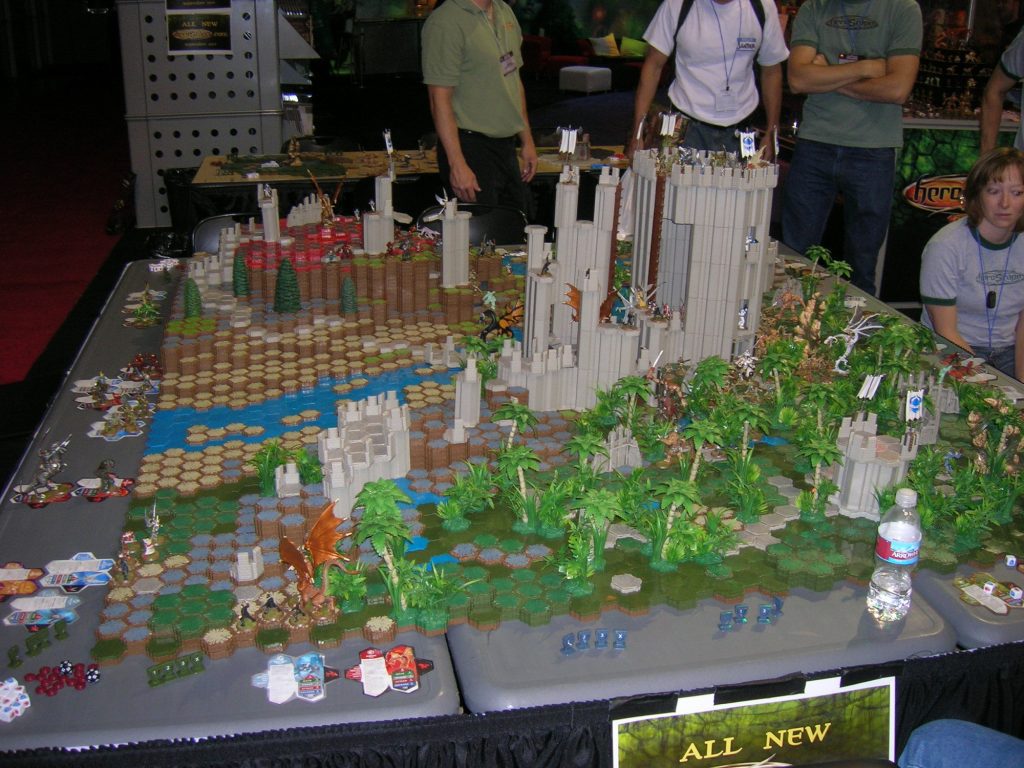

When it comes to games with modular board setup, you can’t get much simpler than Heroscape. In fact, that’s a large part of the game’s charm. The base game includes 85 different terrain tiles that can be stacked and sorted into myriad different combinations.

In Heroscape, designed by Stephen Baker, Rob Daviau, and Craig Van Ness, the players are controlling armies comprised of different types of units with their own proscribed stats such as movement, attack, and defense. The goal: move your armies across the terrain to try to gain a tactical advantage in an attempt to wipe out your opponent’s armies before all of your own armies are defeated. All of the combat in the game is handled by rolling dice. The better your advantage is, the more dice you’ll get to roll.

With somewhere in the range of 30 expansions and many of those adding even more terrain tiles, the only limits to the world that you can construct is your imagination. Were it not for this modular terrain aspect of Heroscape, it is highly doubtful that it would endure for as long as it has. Being able to world build gives the game a high degree of replayability.

For some of you reading this, Heroscape was your first brush with modular board setups. That wasn’t true for me, though. While arguably more customizable than many games out there, Heroscape isn’t a very complex one. The next game on this list incorporates both of these – modularity and complexity – and it does so marvelously.

Catan

One of the first things that amazed me about Catan was the way that the different hexagons that make up the landscape could be shifted around from one game to the next. In every other board game that I had played up until that point, the actual game board was always static and never changing. In Risk, for example, you could always count on Africa being located to the south of Europe, and Australia was always going to be hanging out directly below Asia.

This aspect of most of those games left them feeling very same-y and predictable after a while which made them feel intensely boring and uninspired after many plays. But the ever changing board state of Catan was exciting. I could go into each and every game knowing that this session was going to play differently than any of the previous. The next game on this step ladder is not only a more difficult game to play, but the variation in initial board states can really ramp up the difficulty significantly or it can make things much, much easier.

The Oracle of Delphi

In The Oracle of Delphi (which I’ll just call Delphi), by Stefan Feld, Zeus has set out 12 different tasks for you to complete and you are racing to become the first person to accomplish all twelve. There will always be 3 specific types of monsters (different colors) to defeat, 3 statues to erect at the building sites spread randomly across the map, 3 offerings to be delivered to specific colored temples, and 3 shrines to be erected on islands matching your player color.

You will be given 3 dice that have six different symbols (colors) on their faces and the results of rolling these dice will dictate which colors you will have at your disposal to carry out actions on your turn; actions such as moving your ship, collecting an offering from an island, or fighting a monster. Along the way, the players will receive assistance from the gods in the form of helpful, one-shot rule breaking abilities and will also receive favor tokens which will allow them to alter their dice results if they come up unfavorably. The first person to accomplish all 12 of their tasks and return to Zeus will win the game.

Unlike most of Stefan Feld’s earlier works which see the players gathering up victory points from various sources in order to accumulate the most, Delphi is a pure racing game. In order to complete the various tasks, the players must be able to move efficiently from one island to the next to gather whichever resource is needed and to then deliver that resource to the next location.

Since the game board is comprised of several different modular pieces, the layout of the board can significantly change the game by either making it easier by cramming stuff tightly together or by making it much more difficult by spacing things further apart. This high level of customization ensures that each experience with Delphi will be much different than any other previous one. It is a true testament to the power of mixing deep strategy with modular board design.

Check out our review of The Oracle of Delphi.

Resource Management/Building: Catan -> Gizmos -> Concordia

Catan

Before experiencing Catan for the first time, the concept of gathering resources and then using those resources to build things in a board game was completely foreign to me. I can still clearly recall the feeling that came along with that first time the dice were rolled and my towns started producing and I can vividly remember the stress that came along with watching my hand growing ever larger with the threat of the robber hanging over my head. That rush was something I’d never experienced before and it kept me coming back for more.

After awhile, though, I began to realize something about Catan that wasn’t immediately obvious from the get-go: regardless of your starting position, regardless of your holdings, whether or not you received any resources during the course of the game was almost entirely up to chance. If the dice fell in your favor, then you would do well. Otherwise, the opposite was true. So, I began looking for new games that gave me a similar feeling – the feeling of accumulating goods and then transforming those goods into things that help you obtain even more – but would allow me more control over my fate. The next game on this list fits the bill nicely.

Gizmos

In the game of Gizmos, a Phil Walker-Harding invention, the players are literally building point generating machines. In between the players is a marble dispenser and a set of cards. Each of these cards has a marble cost associated with building it. On their turn, the player will have the option to draw a colored marble from the dispenser to add to their pool, build a card from the card display, take a card from the display to be built on a future turn, or draw cards from one of the face down decks and choose one to immediately build or file away for later.

After being built, a card will provide the player with a new power or a better version of an old one – powers such as allowing the player to draw extra marbles, scoring victory points each time a specific color of card is built, or to substitute one color of marble for a different one. As more cards are added to the player’s machine, the player’s turns erupt into cascading card combos that will (hopefully) net them a great deal of points. When the game comes to an end, the player with the most points wins.

When I talked about Catan previously, I talked a little bit about the role of luck in the game and how it took a lot of control out of your hands. While the role of luck is not entirely absent from Gizmos (random cards draws, marble draws, and marble dispensations), there is still enough information available to the players at any given time for them to make intelligent, strategic decisions and there are enough methods in place for the players to drastically increase their odds of obtaining whatever it is they’re wanting to obtain that the role of luck feels almost entirely absent from the game.

More importantly, though, Gizmos is a game where you start with very little, but steadily build up to a lot. Each card added to your tableau opens up new possibilities and new avenues to pursue. Gizmos is a definite step up the ladder from Catan because of the complexities of how these different possibilities work together and play off of each other. Catan is pretty straightforward – get stuff, build stuff, and try to be the first to score ten points. Gizmos is on a whole other level. The next game on this list is a lot more constricting and much more difficult to master but still gives that same feeling that watching your coffers overflow and watching your empire expand does.

Concordia

Just as in Catan and Gizmos, the players in Concordia don’t start off with much – a couple of pawns on the board, a few generic supplies, and a little bit of money – and then spend the rest of the game investing those resources into expanding not only their reach, but their opportunity as well.

Whereas Catan uses random dice rolls and Gizmos uses randomly dispensed marbles to drive their engines, Concordia uses cards. Each player is provided with an identical set of cards at the beginning of the game. Each of these cards has a very specific function and the players will take turns playing a single card at a time to perform their function. New cards will be introduced during the game that players can purchase and add to their decks. Some of these cards provide new functionality and some are just better versions of the generic starting cards.

Not only do these cards provide their functional powers – building, getting coin, gathering resources, adding new workers to the board, etc. – but these cards are also how the players will score their points at the end of the game. Each card is associated with a specific scoring type and the more of a specific type a player has collected at the end of the game, the more they will score for that particular scoring type. For instance, the Saturnus scoring awards players victory points for each province with one of their houses in it. This score is multiplied by the number of Saturnus cards the player possesses.

Concordia, created by Mac Gerdts, is a heavy game that takes a few plays to really wrap your head around. It’s the kind of game that rewards careful planning and impeccable timing. While the game is easy to understand mechanically, it has a lot of depth that isn’t immediately obvious on the surface. It is because of this that Concordia sits firmly on top of this ladder. It’ll only take you a single play to understand why Concordia is held in such high regard. It’s easily one of the greatest games ever created.

Expandability: Catan -> Terraforming Mars -> Age of Steam

Catan

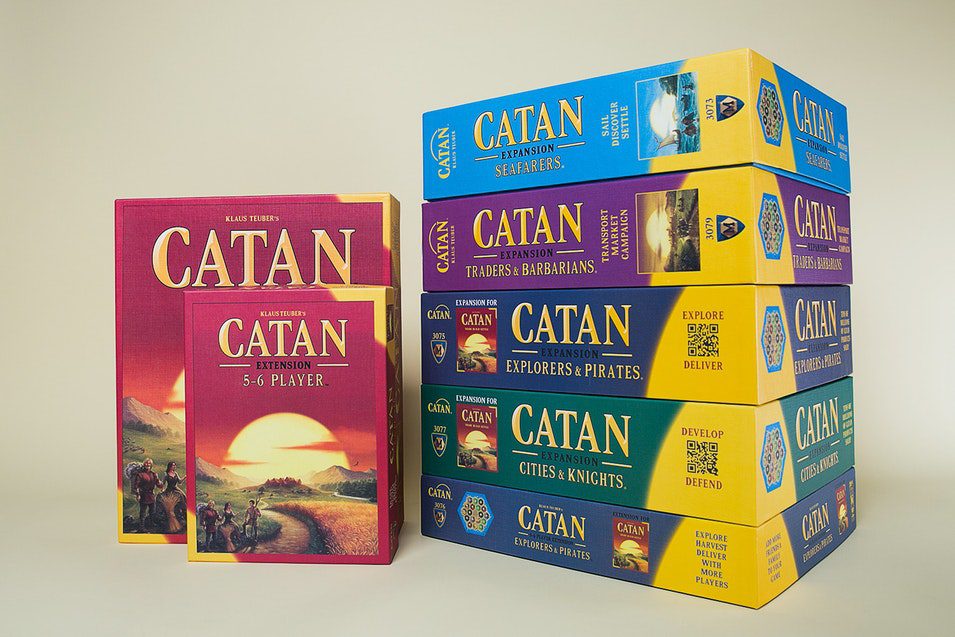

As mentioned in this article’s opener, when I first encountered Catan, it impressed me in a lot of different ways. Perhaps the most compelling aspect of the game for me, though, was that if you ever got tired of playing the base game, you could spice things up a bit by adding in an expansion. This was a concept entirely foreign to me at the time. My only real encounters with games up until that point had been with games like Monopoly or Scrabble which were essentially the exact same game every time that you played them and after what seemed like the one trillionth time, they’d start feeling pretty stale.

Suddenly, here was this game that with the swapping out of a few cards and the addition of some new components was like an entirely new game! That just blew my mind and it didn’t take long before I’d acquired the only two expansions available to me at the time: Cities and Knights and Seafarers. As of this writing, there are now at least 9 different Catan expansions and dozens of Catan spin-off games. Each of them changes the game in some fundamental way such as adding new scoring mechanics, new resource types, and even new end game conditions. It’s like downloadable content in cardboard form!

As great as these various expansions are, they do suffer from some issues. Firstly, most Catan expansions require some very specific things to be done before they can be used. Cities and Knights, for instance, replaces the Development Cards in the base game with several sets of cards in different colors while Seafarers requires you to construct a scenario out of the different map tiles before you can begin playing the game. Secondly, most of these expansions cannot be used together. With very few exceptions, you’re essentially forced to pick and choose between them.

Still, though, the very fact that you can buy a small expansion and breathe new life into a game that’s growing stale is exciting. The next games on this step ladder have mastered the art of the expansion and offer up more complex challenges than Catan.

Terraforming Mars

In Terraforming Mars, by Jacob Fryxelius, the players are controlling different corporations that are working together to settle and terraform the red planet over a course of multiple generations. As the game begins, the surface of the planet is not very conducive to life. It’s very cold, lacks an atmosphere, and is entirely devoid of water. The players are going to be changing that. This is accomplished through the clever usage of various cards which they will acquire throughout the course of the game. Some of these cards will gain them the money needed to buy other cards and use certain card abilities, some will help them gain and/or spend resources more efficiently, and others will allow the players to spend these resources in order to eventually make the planet hospitable.

As the players carry out these different tasks, they will be earning victory points and when the game comes to an end, the player who has scored the most points will win the game. The game also includes milestones (which are victory points that can be purchased in-game if you’ve met the conditions) and awards (which are end game scoring conditions that you can pay to activate during the game).

As of this writing, Terraforming Mars has a total of four different expansions (with a fifth one recently announced) and there’s no end in sight. It’s a brilliantly designed game system that allows for the easy addition of additional content. The first expansion is just an alternate board. It changes up terrain, awards, and milestones which can change up your usual points of focus. Venus Next adds more cards, more companies, and a new game end condition. Prelude adds another deck that jump starts production. Colonies adds a new game mechanic (colonies) that produce resources for you as long as you stay on the colony.

Each of these expansions are very easy to incorporate without any of the convoluted scenario setup shenanigans that you find in many Catan expansions. Also, while not recommended, instead of having to pick and choose which expansion to play with, you could throw them all together if you so chose.

Terraforming Mars is all about constructing an efficient point/resource/money producing engine and then watching it go. Sure, Terraforming Mars might not have as much available expansion content as Catan does (which is to be expected since it’s a much younger game than Catan is), but the base game and its expansions offer a lot more complexity and opportunities for strategizing than Catan does. That being said, the next game on this list not only offers a lot more complexity than Catan and Terraforming Mars combined, but also has much, much more expansion content available for it.

Age of Steam

When it comes to expansions, Martin Wallace’s masterpiece Age of Steam is like jumping out of the frying pan and into the fire. At the time of this writing, Age of Steam has well over 100 expansions available for it. Each of these expansions requires the base game to play and, when it comes to game setup, some require very little effort to setup while others create very different and unique circumstances. Generally speaking, some expansions are similar in complexity to the base game but play better at different player counts. With other expansions, it’s like you are playing an entirely different game. With very few exceptions, none of these expansions can be combined, though, as they are essentially stand-ins for the base game.

Age of Steam takes place during the time when the steam locomotives reigned supreme. The players take on the roles of railroad tycoons trying to spread their influence far and wide in an attempt to make more money than their opponents. At its heart, Age of Steam is a pick up and deliver game where the players are tasked with trying to move colored cubes from one city to another by building new tracks and upgrading their locomotives so that they have greater reach. At the end of the game, players will earn victory points based on their final income as well as how much they’ve built during the course of the game.

When the game begins, the map is pretty barren and is dotted here and there with a few starter cities. Each of these cities has a colored background that corresponds with the colored cubes that the board is randomly seeded with during setup. Each cube can only be delivered to a city of a matching color (i.e. – blue cubes can only be delivered to blue cities) and while you might be tempted to think that this process of laying track and delivering things is where the glut of the game’s activity takes place, you would be wrong.

Central to Age of Steam is the board that contains the income track, the shares track, the locomotive track, and the turn order track. Before anything else in the game happens, the players take turns taking shares. For each share taken, the players receive an extra $5 (each player starts with 2 shares or $10). Then the players bid for turn order. The players that win first and second place in this bid have to pay the full amount of their bids with each successive player paying less.

Turn order is important in this game because it determines who gets to take the building and delivering actions first and it also determines who gets first pick of the special actions from the ones printed on the goods board (which is where the cubes placed in future turns come from). These special actions allow players to cheat the system on their turns in interesting ways such as allowing a player that might not be in first place to have the ability to raise their locomotive’s level by 1 or by allowing them to build extra track on their turns.

After turn order is determined, the players take turns building things and then delivering goods. The more cities or towns that a player can move goods through using their own tracks, the more they will increase their income in future rounds. But move a good using a track owned by an opponent and they will earn for that opponent instead. And this is just a high level overview of the game. Age of Steam is a game absolutely rife with opportunities for strategy as well as screwage. It’s just as much about improving your own lot as annihilating your opponent’s.

The expansions for Age of Steam are typically additional maps with some additional components and, occasionally, new mechanics. For instance, the Montreal metro map is just a new map. There is a zombie invasion map that adds zombie minis which chase your goods around the game and pillage your train lines. The disco inferno map includes multiple different boards, etc. There’s even a map that takes place on the moon! It is because of the enormous library of expansions as well as Age of Steam’s deep complexity that it sits above the other two games on this list. If you’re looking for an expandable game that will last you forever, then you can’t go wrong with this one.

Point Salad: Catan -> Troyes -> Teotihuacan: City of Gods

Catan

For the uninitiated, the term “point salad” refers to a board game mechanism wherein the players are tasked with scoring victory points with those victory points coming from a wide array of sources. In Catan, for instance, the players earn points from the number of constructions they’ve completed, the types of constructions they’ve completed, various cards they may have collected, and also whether or not they possess the Largest Army or Longest Road cards. The quest is to be the first to score 10 points, but it’s left up to the players how they go about achieving that goal.

Before Catan, I’d never encountered anything like that before in a game. Other endgame victory conditions were of the “last man standing” or “have the most money” variety. There was always a clear goal and a singular path that I could follow to get there. Those types of games often ended in one person winning by a very large margin. Those games were typically over even before the game had actually ended. There’s only so far you can fall behind someone in such a linear situation before the writing on the wall becomes clear.

Catan changed that for me. Being able to swoop in from behind and snatch victory from the jaws of defeat with one lucky turn filled me with an excitement and thrill that I longed to relive again and again. That was the beginning of my point salad addiction and when it comes to that, Catan is on the lighter end of the scale. The next game on our list pushes the point salad envelope.

Troyes

Troyes, designed by Sébastien Dujardin, Xavier Georges, and Alain Orban, is a dice rolling game in which the players are working to build up the city of Troyes over the course of four centuries. The city is divided into different sections representing the religious, military, and civil aspects of the city and each of these sections has a specific color of dice associated with it.

Each round of the game begins with the players collecting a number of different colored dice (based on how many workers they have in each city section) and then rolling those dice to form their pool. Then the players take turns using those dice to take different actions such as fighting off invaders, building onto the cathedral, gaining influence, or adding extra workers to the various city sections in order to increase their workforce. Players can even buy dice from other players which is useful if you’re not entirely thrilled by your dice rolls or you just want to deny an opponent the usage of certain of their dice.

At the beginning of the game, players are given secret objective cards which will provide them with a lot of victory points at the end of the game depending on how well they have met the objectives shown on the cards. These cards reward points for things such as how much money they end the game with, how much influence they end the game with, or the number of workers they have present in certain buildings when the game comes to an end. In addition to these points, the players will be scoring points throughout the course of the game for placing workers on certain action cards, countering the various events that come up, and by assisting with the construction of the cathedral.

Unlike Catan, Troyes is not a race to get a certain number of points. It’s a contest to earn the most and the method of earning those points isn’t as straightforward. At any given time, there are a lot of different considerations to work through… much more than the decisions you’re making in Catan. In terms of point salad games, that is why Troyes sits above Catan in this list. As complicated as it is, though, Troyes doesn’t hold a candle to the next game.

Teotihuacan: City of Gods

In Teotihuacan: City of Gods (simply referred to as Teotihuacan from here on out), the players command a set of workers (represented by dice) as they work to construct the game’s titular city. The game board is a rondel with 8 different action locations along the rondel’s path. On a player’s turn, they will select one of their dice and then move that die around the rondel 1 to 3 action spaces and then take one of the available actions from that space. As the workers move around the board, they will level up until they eventually “ascend” (read: pass away) which causes the dice to reset and get placed back into their starting location.

Most, but not every, action space has two common features: the ability to “worship” which lets the player lock a die in place in order to move up one of the temple tracks on the board and/or claim a discovery tile (which provides the player with a special benefit that can be used repeatedly over the course of the game) OR the ability to gain cocoa (which is like a currency used to perform actions and also to feed your workers).

Each of these action locations also has its own special ability that can be used. For instance, some gain you resources while others allow you to build things. Each of these actions becomes more powerful the more dice of your color are present on the tile when you take the action and is also affected by the workers’ levels.

In the middle of the board is what is perhaps Teotihuacan’s most striking feature: the Pyramid of the Sun which will be constructed by the players over the course of the game. It is comprised of a number of double-domino-like tiles that feature different symbols at each corner. When these are stacked on top of each other, they will not only form the pyramid, but they will also score the players points and other benefits as well.

Without going into a ton of detail, the game is played until one of two end conditions occur: the pyramid construction is completed or after the third eclipse phase occurs (triggered by various actions taken throughout the course of the game). The aim of the game? You guessed it – try to score the most victory points. And boy does this game ever have a lot of ways to gain them!

The players will earn points from the following sources:

- points from advancing on temple tracks

- end of game scoring from reaching the end of the temple track

- actions from different action locations (such as constructing noble houses)

- constructing certain technologies

- matching symbols when adding decoration tiles to the pyramid

- reaching the end of the pyramid track

- adding building tiles to the pyramid

- ascending workers (leveling them to 6)

- for having a marker on the avenue of the dead (which happens when workers ascend) during the eclipse phase

- for having moved along the pyramid track during the eclipse phase

- for having different sets of masks (collected from discovery tiles) during the eclipse phase

- you lose points for not having enough cocoa to pay your workers during the eclipse phase

If that list has you going cross-eyed, it’s understandable. That’s a lot of things to consider and a lot to take in. That is why Teotihuacan, created by Daniele Tascini (one half of the duo that gave us Tzol’kin: the Mayan Calendar and The Voyages of Marco Polo), sits firmly at the top of this step ladder. With so many options and so many different avenues to victory, it’s point salad at its very best.

Special thanks go out to my fellow writers Justin Gibbons, Jesse Fletcher, and Andrew Plassard for their insights into some of the games in this article.

While you’re here, make sure to check out our Top 6 Catan Strategies for Turning Your Losing Streak Around.