Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

Rock Hard: 1977 (2024, Devir) is one of the best times I’ve had at a table this year, despite a design that I, along with six different people who joined me for my review plays, collectively described as “meh.”

In fact, I think the best way to approach this game is the way I scored it—Rock Hard: 1977 is a game where your goal is to lean into the theme and have maximum fun laughing at the chaos. If you play it as a strategy gamer trying to win, a dozen or more flaws will surface faster than you can say “space cadet.”

If you follow the tabletop industry even casually, you’ve already heard of Rock Hard: 1977. Gosh, no less than the New York Times has already heard of Rock Hard: 1977 and rocker-turned-Jeopardy! contestant-turned game designer Jackie Fox, so I’m going to waste no time talking about how the game plays or what it is about. (I will point you to Jackie’s fantastic designer diary on BGG as a way to dig into the background of the game’s journey.)

Instead, I’m going to spend my time here trying to convince you why you should or should not play this game based on your playgroup. That’s because Rock Hard: 1977 fell into two camps for my two review plays: the right group, and the wrong one. (While I would normally play a game 3-4 times before writing a review, my second play crystalised everything I thought about the game and I am locked in on how I feel. I love it when that happens.)

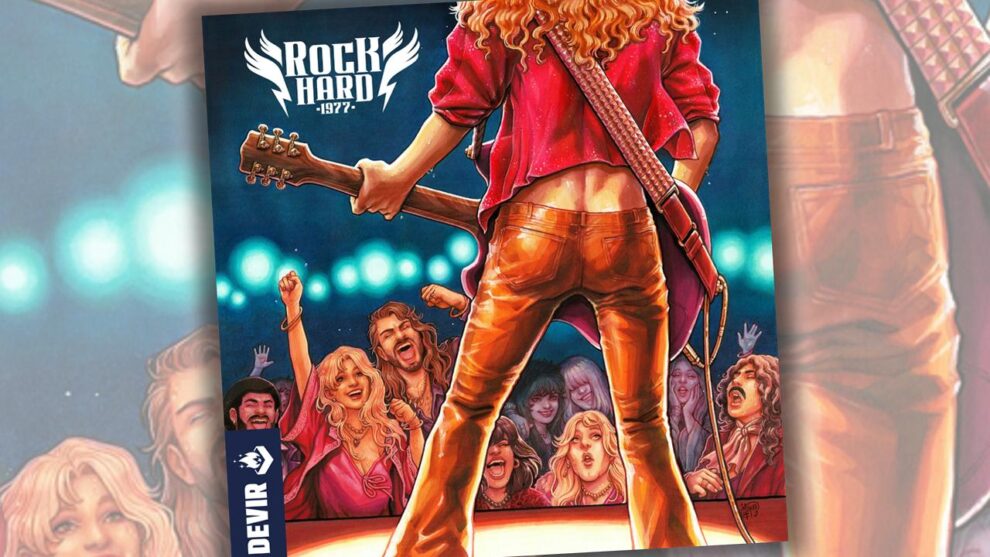

First, let’s talk about the production…which, for fifty bucks, might be the greatest value proposition in our nation’s great history!!

Wait…AND There Are Acrylic Standees?

Everything I had heard about the production of Rock Hard: 1977 turned out to be true.

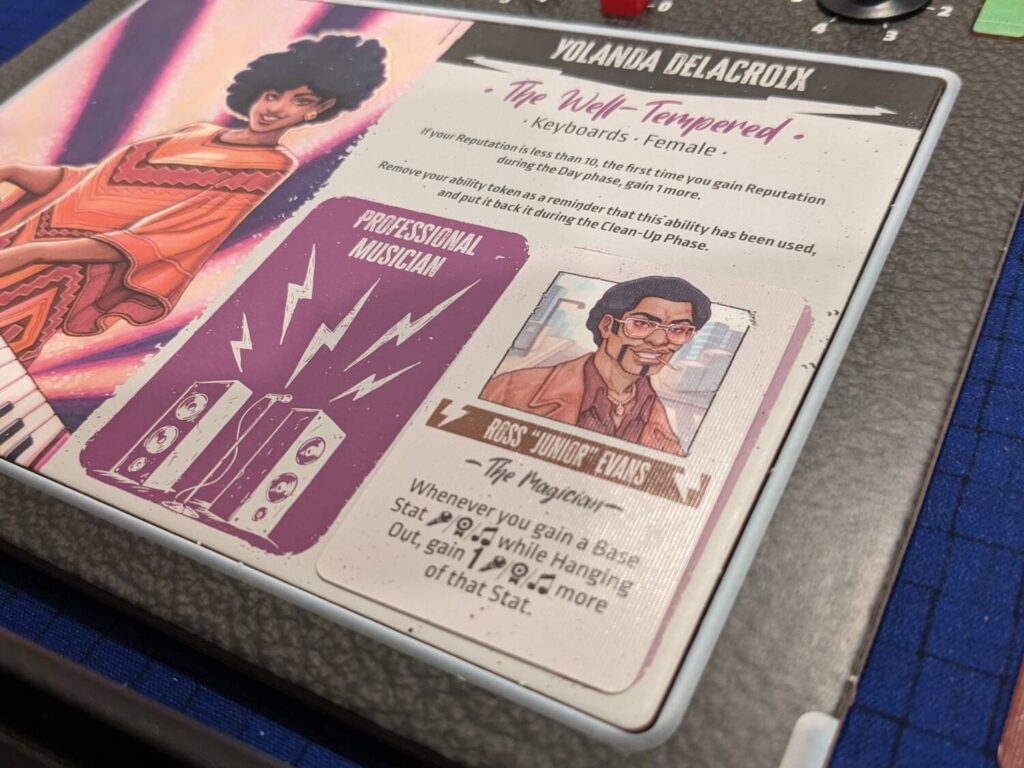

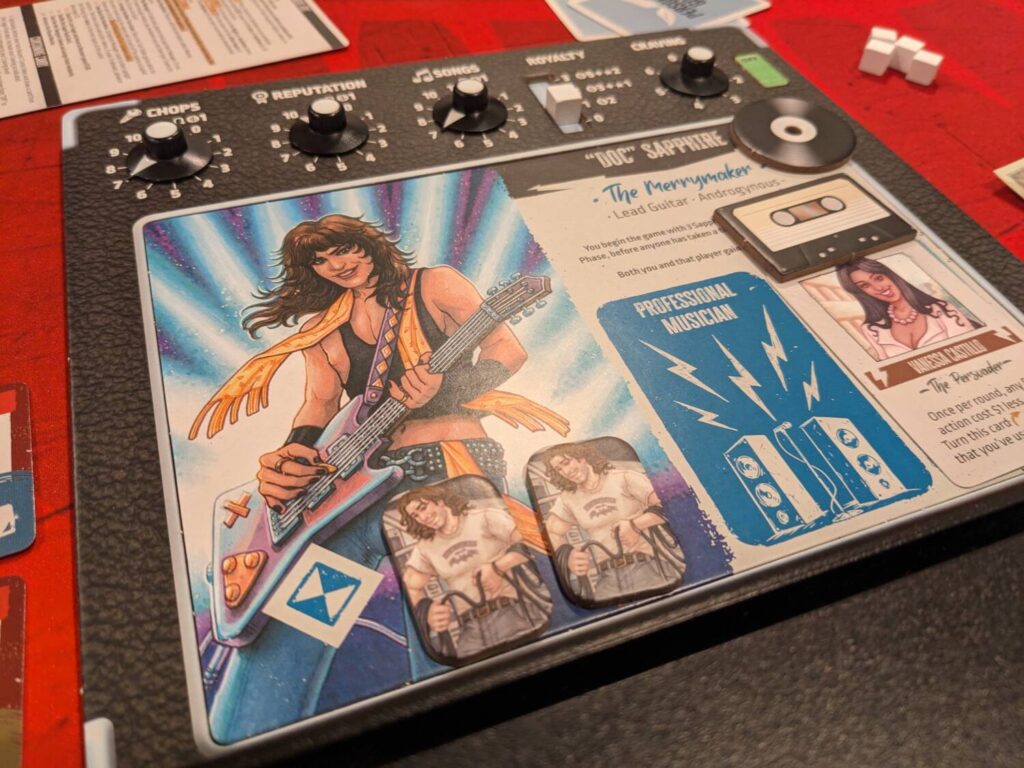

I almost can’t believe the price: $50 gets me possibly the best player boards of the year, with stat tracking that does a cute job of letting me track my artist’s reputation, songs, and “chops” with a slider cube, and a place for my well-drawn artist board to fit snugly below the knobs. (I’m already having visions of what I want out of a sequel themed around hip-hop, like “Fresh Jams 1986”, with player boards that look like the decks a DJ might spin on.)

But the player board is just one of many great highlights of this production. The player aids mostly nail it, although I wished they would have listed end-game scoring conditions. The rulebook is good, a bit luxurious for a game that can be taught in 15 minutes, with plenty of ways to bring in a gamer that does not play a lot of games. The only glaring omission to the rulebook is a card and power appendix, which would have helped with edge cases (sometimes, player powers, manager powers, and cards in the Hang Out deck break other game rules in ways that created questions during my plays).

The demo tape and record deal tokens are perfect for their respective tasks. The game’s candy (drug) tokens are some of my favorite cardboard chits of the year. The iconography here is so intuitive that I found myself surprised when other players had questions that had been answered earlier in each game (it’s all about the re-teach). Rock Hard: 1977 is one of the few icon-heavy games this year that did not force me to check the rulebook or the player aid for icon-related guidance. (And, even if I did, most icons are explained on the back of the player aid.)

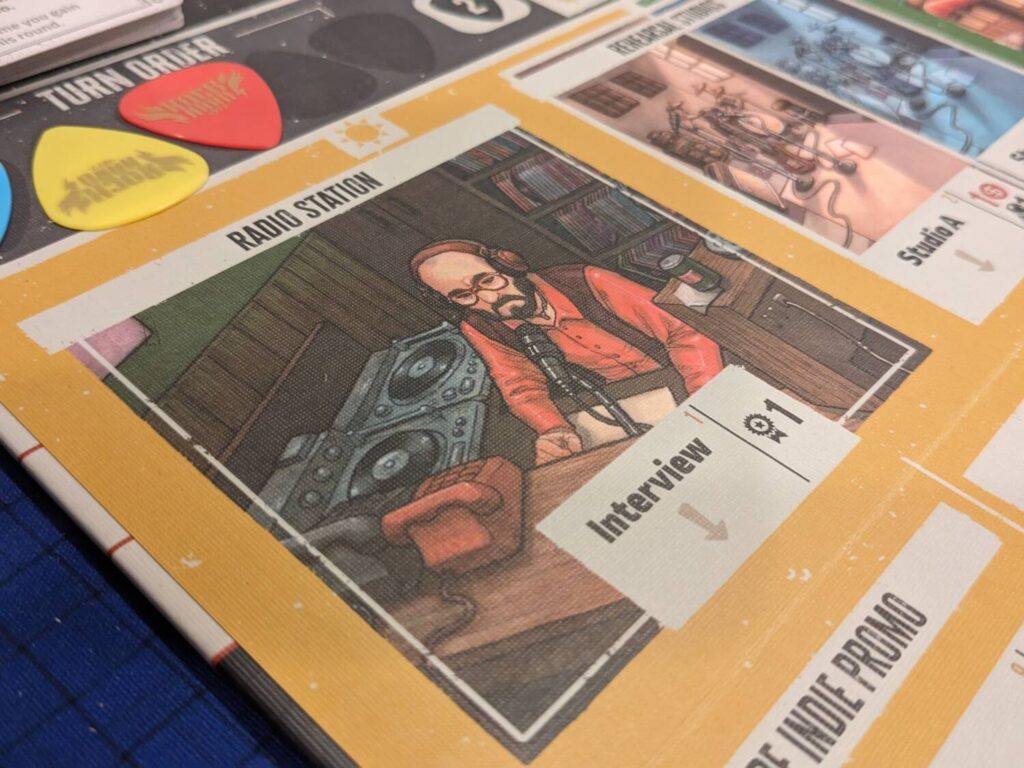

The main board looked really busy when I first laid it out to do a dummy-hand walkthrough of the game’s actions, but I was quickly able to spot all the things that matter—which spaces are piece-limited versus open to all players, the breakdown of each day’s three phases, and which spaces were gated by requirements listed in blue. It was small, but so intuitive: even though rewards (black) and costs (red) are denoted by color, the rewards are listed with a dollar icon first and then a number, whereas costs are reversed, with a number followed by a dollar icon.

Speaking of cash…

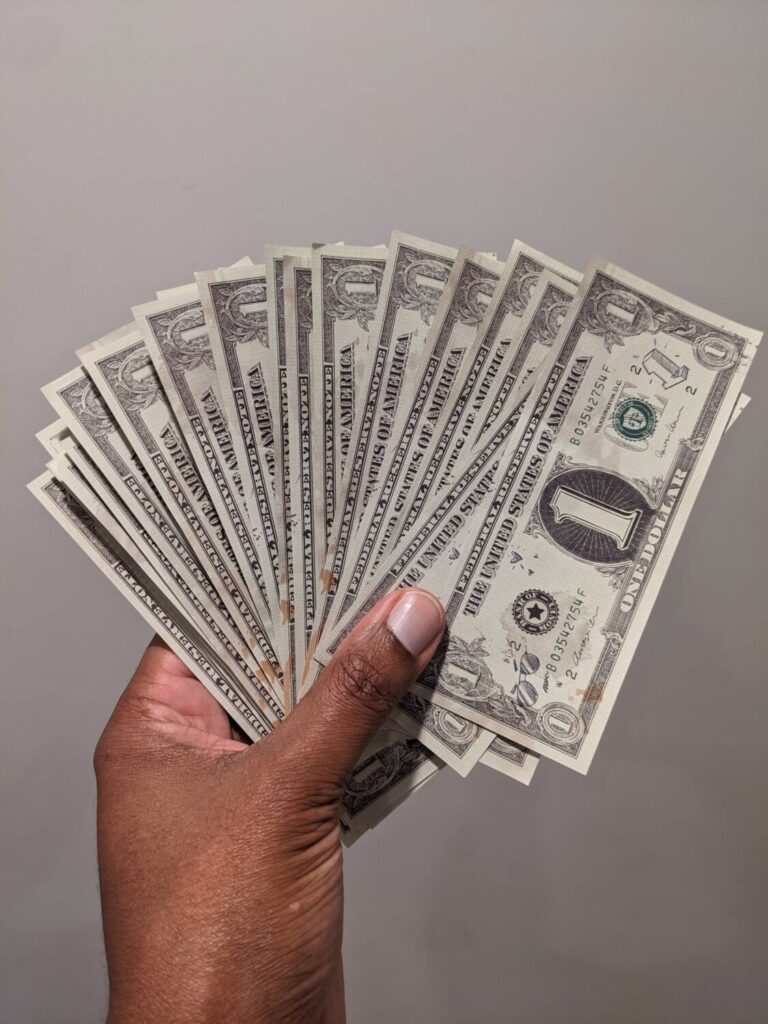

This is the Greatest In-Game Money Ever Made

The paper money provided for Rock Hard: 1977 is the single greatest tabletop currency component ever made, period. I won’t go so far as to say “by a wide margin”, but the temptation is there.

If you have perused some of my other content, you know that I use poker chips for the majority of games that require money. It’s faster for the banker to distribute funds—that’s the main reason for using chips anyway—but the chips feel good in the hands and help stave off boredom as I watch other players labor through their turns.

But around the time that Magnate: The First City came along a couple years ago and re-introduced me to what quality paper money could look like (right down to having a wallet that helped keep player money secret), I started to at least listen to the argument that quality paper money could work in board games. Usually, the argument gets flushed because an 18xx game or something older like The Game of Life, Pay Day, or Monopoly gets tabled and I have flashbacks to my childhood when paper money would rip simply by having another player stare at it.

Rock Hard: 1977 makes all those problems go away.

The bills are incredible. First, they correct the most common mistake that other companies try to get away with: the bills are the actual length of a regular American currency note. So, the game’s bills pass the eye test, to the point that multiple players suggested bringing the Rock Hard: 1977 money to a club, or a grocery store, or a place that still accepts cash (a shrinking community, for many reasons) to see if they could get away with tricking a shopkeep into thinking that the board game money is real.

The stain of the bills, the discoloration, is so good with the money here. I love that many of the bills appear to be written on, or smudged, or stamped, or otherwise abused, like every dollar I had in my pocket when I was a kid. I love the textured feel of the bills too, like they have been handled a bit before being shipped with the game.

The money of Rock Hard: 1977 is so good that I’m almost angry Devir didn’t take one final step: I wish the bills were wrinkled. Maybe the right way to say it is “crinkled.” I wanted this money to be rumpled, like I had it stuffed in my pocket instead of placed cleanly in a wallet. (Let’s go further: shouldn’t the game feature rock-themed wallets for each player to store their cash?)

Unless something more miraculous happens between now and the end of 2024, the money components in Rock Hard: 1977 are going to cruise into my Best Component award for 2024. It’s almost worth the price of the game to own a copy of these bills for yourself, and I will definitely be using this cash for any other game I have that features a small pool of American money ($1s, $5s, $10s) for its components.

I’ve spent a lot of time talking about the production of Rock Hard: 1977 because it somewhat badly outshines the quality of the design. I hate to admit that, but across my two plays, I found myself questioning a lot of the decisions that went into the original design as well as any development that got us to the finished product on my table.

This is the rare case where that didn’t matter as much to me, because I had so much fun playing the game. That leads us to our final thoughts: who is this game for, and who is it definitely not for?

The Wrong Audience

My first play of Rock Hard: 1977 was with two of the guys in my Chicago-area strategy gaming group.

Almost from the beginning, some of the game’s design cracks appeared. Rock Hard: 1977 is a worker placement game (accommodating 2-5 players) with some of the standards of benchmark Eurogame design: public milestones, personal goals (some secret, some open), limited chances to take the best actions, worker placement spots that are strictly better than others at the same action locations, and a chance to burn part of your round to ensure you go first in the next round. In some ways, this is a by-the-numbers exercise in modern tabletop experiences.

One of the game’s public milestones seems almost broken, and it appeared during this first play: a player could earn points simply by quitting their job. Quitting a job is a free action that can be done on a player’s turn, and mainly means that a player has to find other ways to earn money by playing shows or donating blood for a buck.

It was hilarious to watch the hard-core strategy gamers talk about this: as the first player in the first round, should I just quit my job on the first turn of the game to ensure I lock up those points? In a game where the end-game is triggered when a player crosses the 50-point threshold, five points is pretty huge. In the spirit of fairness (turn order is determined by calling out who last sang in the shower, another funny moment), no one did it on their first turn…but by the third round, someone quit just to score the points.

This was just one of many elements that help steer Rock Hard: 1977 into a more “Ameritrash” style of design, which doesn’t work for players who want to deterministically work towards building a winning strategy.

Some jobs require a die roll to determine wages. In this first game as a hotel porter, I rolled a five or a six each time I went to work, ensuring I made $3 instead of $1-2 each round. Money is pretty tight in Rock Hard: 1977 early on, so I had a massive advantage simply by rolling a six-sided die.

The game has a “Random Gig” each round that can be played by all players. In one of my games, a card granted every player a chance to permanently boost one of their “base stats” (rep, songs, chops) all the way to the max score of 11…for FREE. This was funnier because in that game, I spent the previous two rounds trying to build up my songs stat to play at the largest venue in the game, Carter Stadium.

If only I had known that I could just, you know, do that for free later.

Taking extra actions comes down to a card draw from the Sugar Rush deck. Some of the Hang Out cards are strictly better than other cards. Some of the Personal Goals are just easier than others, and those are again dealt out as a random card draw, for the same number of points as other goals. Turn order is essentially meaningless in a lower player count version of the game. I won these games mainly because I committed to going last every round, ensuring I would score two points for taking a worker placement spot that was numbered as the last one available. Each time I did this, I was surprised that I didn’t even take a hit when searching for worker placement spots to take meaningful actions.

You get the idea. There’s a lot of things here that turn Rock Hard: 1977 into a literal roll-of-the-dice, and that left the strategy gamers in a tough place.

“The production was a 10/10 for me, but the game play was much less,” one of the strategy gamers said later. “The mechanics themselves were pretty ‘meh’ to me.”

In that first game, we didn’t read that much of the flavor text on the cards. We laughed from time to time at the names of the Random Gigs and loved it every time someone tapped their Manager power to boost an action. The theme was there, but we didn’t lean into it as hard as we could.

If your group is made up mostly of strategy gamers, I would pass on Rock Hard: 1977 unless you also play games with, say, your partner, someone who loves the music theme and is comfortable with a large amount of luck that determines the outcome. I’ve won my two plays, and I’m not sure I should say that I played better or made better decisions than the others at the table. It didn’t feel that way.

My second play was with my review crew, a mix of newer gamers and seasoned veterans. One guy goes to as many shows each month as I do. Another is a guitar player. All were looking forward to a casual night thanks to a lower rules overhead than some of the other games I get to the table.

That’s where the magic of Rock Hard: 1977 reared its beautiful head.

The Right Group

“I’m not sure which job I should pick—truck driver or car salesman. Car salesman sounds seedier…let’s pick that one.”

“My craving level is already at 5…I’m going to use another candy token. Let’s get crazy!!”

“I get three bucks and only have to take a one-point hit to my reputation? Yeah, put my marker at that bar mitzvah after all.”

These lines, and more, were some of the dozens of times I laughed during the second play of Rock Hard: 1977. I embraced the chaos, and that is the only way to fly to make the game a smash.

Every time someone drew a new Hang Out card, they read the flavor text. Everyone made fun of the player who didn’t make his demo tape until September (the game’s rounds are tied to a month of the year). We leaned into the drug theme. We made inappropriate remarks from time to time…in character, of course. (Remember, it was the 1970s.) I had a personal goal to donate blood three times, so I made a joke every time I went to the blood bank.

When I had to pay for my third crew member, I waved my pile of dollar bills at the other players while making a show of licking my thumb to peel bills out of my hand, like I was Scarface or something. When another player played a gig at the Panda Palace, he joked about finding fame and fortune after playing at “TJs”, the gig locale that looks like a local bar on the game board, for so many months prior to that turn. One player took great pride in skipping work as an executive assistant for the third time, guaranteeing that he was free from the shackles of corporate work.

If you play this game with a group that has time (to the tune of two-and-a-half-hours, an eternity for a game that should have been done in 90 minutes or less), loves the theme, appreciates a spectacular amount of “swinginess”, consumes a can or two of Schlitz and has the desire to let a game make memories, Rock Hard: 1977 is a fantastic time at the table. Mechanically, it is not doing anything an experienced gamer hasn’t seen before.

But you’ve never seen it in a package this sexy, this lush, or this loud.

As an event game, Rock Hard: 1977 checks every box. It’s a good-looking toy in a box delivered by one of the most consistent publishers in tabletop. While I’m not confident we will be talking about this in a year or two, it was such a pleasure to sit at the table and embrace its attempts at thematic storytelling.

If you have the right group, give Rock Hard: 1977 a look. Just take it easy on the drugs, OK?

The part I got really lost on in your article is where you talked about gaining points for quitting your job. That’s not something that happens in the game. You may quit your job at any time, but you do not get any reward for it.

Kellyn, thanks for the note! You are mostly correct. However, one of the milestones that can be used in the game rewards a player with points if they quit their job. Otherwise, there’s no additional reward for quitting. Thanks for reading!