Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

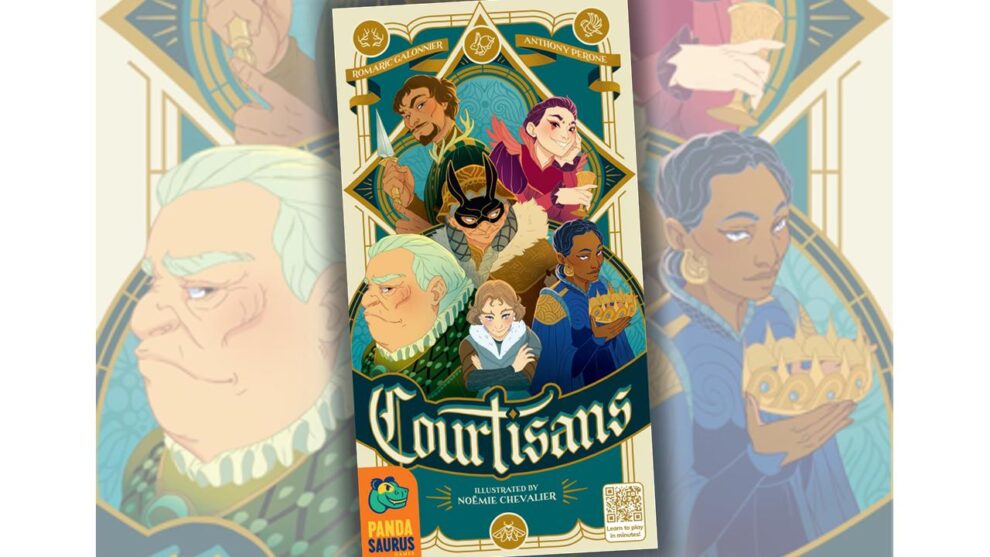

If you’re squinting at that title, wondering if you’ve missed something, you haven’t. In contemporary usage, “Courtesan,” with an “e,” refers to the women who exchanged sexual favors for influence back when royal courts were a thing. Courtisans, with an “i,” is not about courtesans. A more accurate English-language title for this game would be Courtiers, the members of a royal court who buzz about royalty like flies around rancid meat, but we don’t live in that world.

Thank goodness we don’t. This world is more fun. Courtisans is, of course, French for “courtiers,” but it’s surprising a major publisher like Pandasaurus looked this cultural discrepancy dead in the eye and decided to plow ahead. God bless. Feels like the old days of board game publication, before translation was handled by professionals.

I’ll See You in Court

Courtisans is a wondrous little card game concerning six noble families who jockey for influence. The rules are misleadingly simple. From a deck full of members of those families, each player draws three cards. On your turn, you distribute your three cards as follows: one goes down in front of you, another goes in front of an opponent of your choosing, and the third goes either above or below the central board, a cloth mat that depicts a banquet table with the head of each family sat to either side of the monarch.

The cards you place in player tableaus, including your own, are ultimately used for scoring. The cards surrounding the board determine what the individual family members are worth. If the Stags have more cards above the board than below, for example, then every Stag card a player has will be worth a positive point. If the Frogs have accumulated more cards below the board than above, they cost players points instead.

As it should happen, every single game of Courtisans that I’ve played has ended with the frogs in the negative. There may be some implicit bias at work here.

Each suit has a small number of cards with special powers. Not only are they mechanically simple, they also interact with the rules in obvious ways. My favorites are the spies, who are placed to their locations face-down. Nobody is allowed to look at them until the end of the game. In a game where the margins on familial status can come down to a single card, one or two well-played spies can make all the difference.

The other wrinkle enriches the metagame: each player starts with two hidden goals. Instantly, every card play becomes an act of divulgence. If a player opens by confidently placing a Moth card above the board, other players may try to crash the Moth family’s value like we haven’t seen since ’29. It becomes a game of discussion, of negotiation, and inference. Every card is a twinge in the spiderweb.

The real beauty of all of this is that, in reality, most of your card plays don’t mean anything. At least not at first. But then one family becomes laden with so many negative cards on the board that handing those out to other players becomes a statement. If someone seems to be doing too well—take it from me, you never actually know how anyone is doing until the game ends—they might get firebombed. If someone’s behind, other players may chuck positive points in front of them for safekeeping. It’s silly, it’s low-stakes, and it is above all else fun.

That’s what makes Courtisans so enjoyable, and what makes it an object of anthropological fascination: The way in which collective thoughts shift as the game continues. This is not a game about finessed control, about careful planning, about intentionality. It’s a game of wild luck. It’s a social game, really, one about both the verbal conversations you have across the table and the non-verbal conversations that play out as cards are placed. Designers Romaric Galonnier and Anthony Perone were smart to keep additional wrinkles to a minimum. When you don’t have to think about your turn, you’re left free to think about the game.