Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

My favorite type of trick-taking game is one that pits one or two players against the rest of the table. While this sort of design doesn’t come up much in contemporary releases—Mü & More is the only even vaguely recent example that leaps to mind—its origins can be traced back to the middle of the last millennium and the French card game tarot. There’s something about this dynamic, the Me-Against-the-World of it all, that I adore. You are usually only elected the lone gunslinger if you’ve got the firepower to back it up, but it feels precarious to be facing down the rest of the table. In games like these, everyone gets to feel like the underdog.

3 Witches, a game for precisely three players, is just such a trick-taking game. Players bid for the right to be the Lead Witch, tasked with winning exactly three or four tricks over the course of a hand. It is up to the other two players to stop the Lead Witch by forcing them to over- or under-perform. This is harder for all involved than it may initially sound.

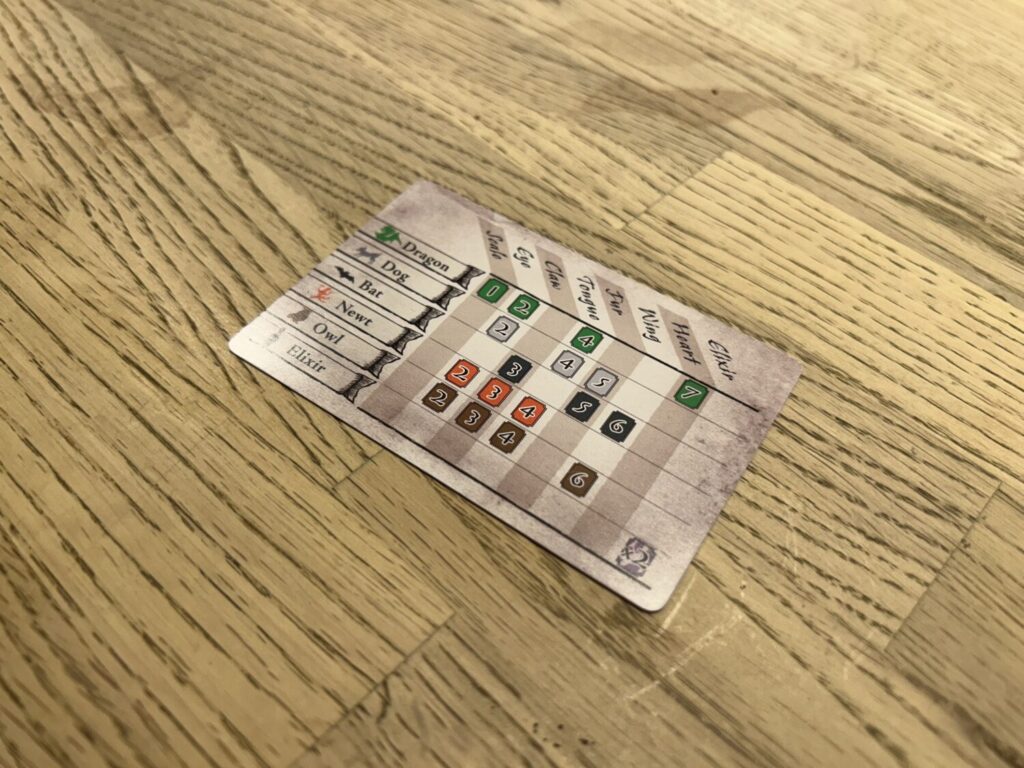

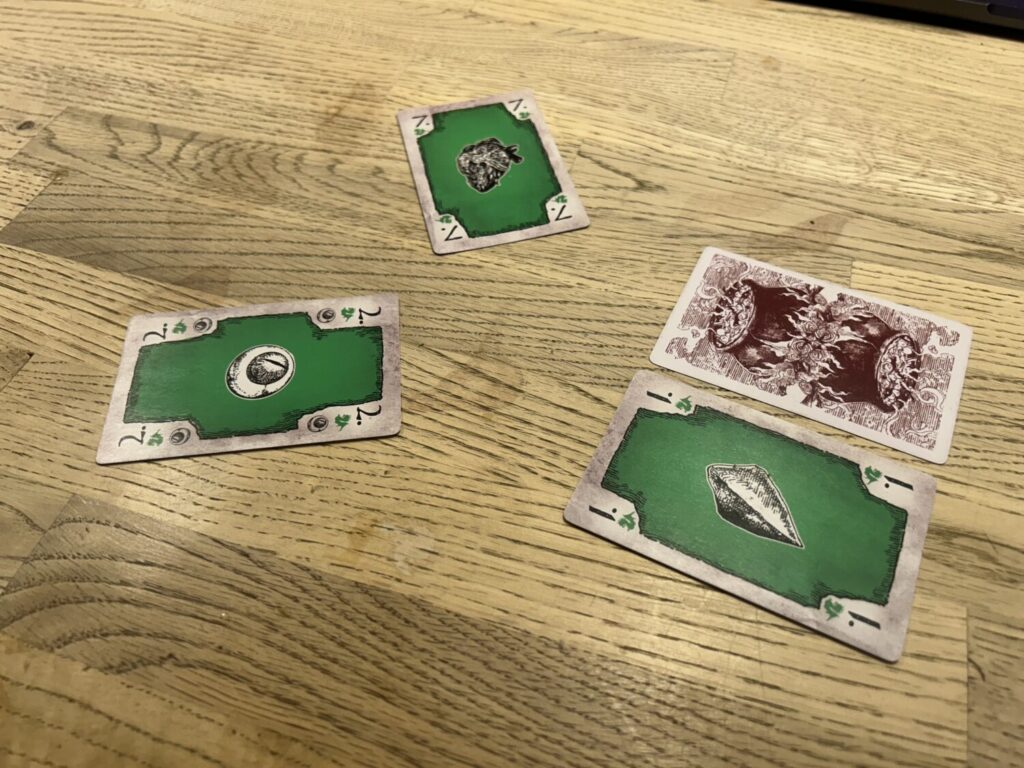

Rather than playing a single card, the Lead Witch starts off every trick—they always lead—by playing two cards. One is face-up and the other face-down. The other Witches have to play cards corresponding to the suit of the face-up card if they can, then the face-down card is revealed. If the Lead Witch or the partners put down two cards of either the same suit or of the same value, the two cards get added together. If they don’t match on either count, the value of the higher card played takes precedence. Say for example that the Lead Witch plays a grey 1 and a green 7, while the two other witches each play a four. The Lead Witch has effectively played a 7 and the others have played an 8.

Rather than playing a single card, the Lead Witch starts off every trick—they always lead—by playing two cards. One is face-up and the other face-down. The other Witches have to play cards corresponding to the suit of the face-up card if they can, then the face-down card is revealed. If the Lead Witch or the partners put down two cards of either the same suit or of the same value, the two cards get added together. If they don’t match on either count, the value of the higher card played takes precedence. Say for example that the Lead Witch plays a grey 1 and a green 7, while the two other witches each play a four. The Lead Witch has effectively played a 7 and the others have played an 8.

While this can feel initially confusing, you settle into it without much fuss, and 3 Witches quickly turns into a tense and fascinating experience. It’s a knotty, mathy beast, one that involves significantly more AP than you’d expect from a game with only 18 cards. If you don’t enjoy combinatorics, this may not be the one for you.

After each trick, both Lesser Witches discard their played card, but the Lead Witch gets to keep one of the two they played. If the Lead Witch won the trick, they pick up both cards and secretly choose one to keep. If the other two players won, they decide as a pair which of the Lead Witch’s cards to toss.

After my first play, I was besotted. My favorite games across all genres are those in which decisions feel murky, in which perfection is an abstract proposition, and that’s exactly how 3 Witches felt. But, as often happens when you fall hard, things got bumpy when we tried to commit.

After my first play, I was besotted. My favorite games across all genres are those in which decisions feel murky, in which perfection is an abstract proposition, and that’s exactly how 3 Witches felt. But, as often happens when you fall hard, things got bumpy when we tried to commit.

After a handful of games, I’ve come to the conclusion that the Lead Witch is often the only player making any real decisions. Given the distribution of cards—no two suits are the same—it’s easy for both of the Lesser Witches to be forced to play a particular card every turn, entirely depriving them of agency. There is clearly room for cleverness in here. Every now and then, a play would crystalize in my mind. But that happened less often than I should have liked. 3 Witches often doesn’t feel like a game of two-on-one so much as it feels like the Lead Witch is rehearsing for a play with two friends there to help run lines. The feeling that something doesn’t quite work seems to be widely shared among the people I’ve played with: in theory, you play 3 Witches until any one player has 5 points, but I’ve yet to have a game last more than two or three hands. People get itchy to move on.

3 Witches is a great idea. It’s more of a deduction and bluffing game than it is a trick-taker, but I don’t mind that. The rulebook notes at one point that the Lesser Witches are under no obligation to play a hand in a cooperative manner—if winning as a team would give your teammate the point needed to win the whole game, ambush at your leisure—and that tells me this game has its heart in the right place. The issue I have is that its systems leave two out of three players in an unsatisfying position, stumbling around in the dark. When things go wrong for the Lead Witch, it’s rarely the active work of the other players so much as it is a math error and a bit of bad luck. The margins are too tight, the intentionality too low. 3 Witches cast one hell of a spell, but it didn’t last.