The year 2025 marks the 40th anniversary of Dr Reiner Knizia’s career as a board game designer – his first published game, Complica, was released in a magazine in 1985 (although he’d self-published games before then as well).

Since then, Knizia has designed and published over 800 games and expansions, many of which are critically acclaimed. Put simply, Reiner Knizia is the landscape on which all other modern designers build their houses.

To celebrate Knizia’s career and back catalogue, Meeple Mountain are taking things back to basics to consider the ABC of Reiner Knizia: one game for each of the 26 letters of the alphabet.

This time: The Letter ‘U’.

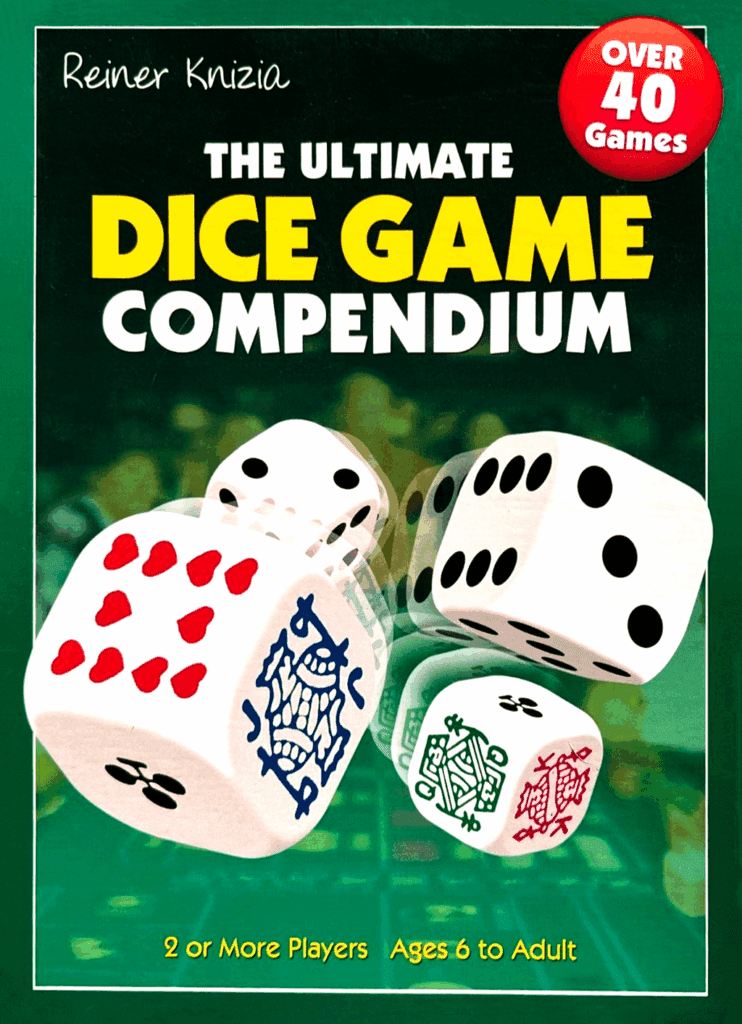

U – The Ultimate Dice Game Compendium (2006)

A few months ago there was a very minor discussion about the number of board games Reiner Knizia had actually designed.

Knizia’s website states “more than 800 games published worldwide”. BoardGameGeek, at the time of writing, lists 809 designs, although that includes expansions and promos. Efka Bladukas, of No Pun Included, suggested on BlueSky that these numbers are vast over-exaggerations. This prompted Matt Montgomery, over at Don’t Eat the Meeples, to attempt to calculate an ‘accurate’ number, settling on a number slightly less than 450, with some caveats.

Before we go any further, I should say that I’m using the BlueSky exchange and subsequent analysis as an example in this article, and am not calling anyone out or protesting against any supposed injustice against Knizia. I have a huge amount of respect for both Bladukas and Montgomery and am a fan of both of their outputs. Their comments and analysis are an excellent example of discussions that often surface about Knizia’s design work, and are far more respectful and reasoned than appears in other corners of the web.

The problems stem from how you award a design credit or define a ‘published’ game.

Hit!, No Mercy and Fruit Fight are all the same design (discussed when we covered the Letter N). The first two even share the same art and graphics. That’s three versions, editions or Stock Keeping Units (SKUs) but one game design. But don’t go thinking that the magic 800 games is down to different versions of the same game – Hit!, No Mercy and Fruit Fight are generally counted as a single ‘game’. If we were considering the total number of versions and editions then the number would be far, far higher:

“I sometimes cannot understand publishers or people who are in the creative business when they do not collect their creations,” said Knizia in a 2021 interview with Nick Murray of Bitewing Games, “Why do you send these children into the world and then forget about them? For me, I’m proud of them and for me I want to see each edition and I keep a copy of every game of every edition and that’s far more than 2,000 different copies now.”

So our Hit!/No Mercy/Fruit Fight example doesn’t explain the 800. But what about Hit! Extreme? It’s the same template but adds a small handful of special action cards and changes the number distributions on the cards. The gameplay is otherwise identical. Is it a second design, should it be counted in the same category as an ‘expansion’ (despite being standalone) or should we simply lump it in with the original design? And then what about its close relative Family Inc., and its ancestors Cheeky Monkey, Circus Flohcati and Star Wars: Attack of the Clones Card Game?

BoardGameGeek’s own W. Eric Martin discussed this issue back in May when considering AllPlay’s forthcoming release of Piñatas and its overlap with both Voodoo Prince and Marshmallow Test. These 2017 and 2020 games are almost the same, and Piñatas uses the rules of Voodoo Prince but with the ending of Marshmallow Test. Is that one game or three? Before Piñatas you could say it was two slightly different designs but the new release may well have fused them into a single mass. Martin put the decision to the community and out of 723 votes, 47.7% felt the games were different enough to warrant three separate entries into the BoardGameGeek database, whilst 38.9% felt they should just be one entry. Each game now has its own entry but its clear that not everyone agrees.

Montgomery’s analysis resulting in around 450 games is conservative – games that are part of a series are reduced to a single point, labelled as ‘reimplementations’. But that approach, necessary for the newsletter scale of the analysis, excludes as much as it filters. Yellow & Yangtze (2018) and HUANG (2024) play by the same rules, differing only in production (and the availability of a couple of small expansions for HUANG). But both are also clear reimplementations of Tigris & Euphrates (discussed in the Letter E). Is that one, two or three games?

What about My City and My Island – siblings sharing the same underlying bone structure but with very different personalities. They’re undeniably a series and employ many of the same mechanisms, but they’re distinct in their intended audiences and experiences. Knizia iterates his designs and, as Andrew Lynch explored with Lost Cities, its fascinating to see how small changes can make different experiences and how large changes can affect the gameplay but not the feel.

Those in the hobby often minimise Knizia’s variants and similar games with language that implies cash grabs and laziness: part of that exchange on BlueSky involved the comment “To be fair that [number] probably translates to like a dozen games rethemed”. Yet Pandemic, Forbidden Island and Fate of the Fellowship are considered to be distinct games despite using the same core mechanic and all coming from designer Matt Leacock. Fantasy Realms directly inspired Red Rising (and had its own sequels in the form of Marvel: Remix and Star Trek: Missions – one game or three?). Whilst the inspiration for Red Rising is acknowledged, it still counts as one of Jamey Stegmaier’s games, co-designed with Alexander Schmidt (II). How different does a design need to be for us to consider it an ‘original’ design? What about Knizia’s The Quest for El Dorado and the deck-building originator Dominion? We, as a hobby, like to quibble over Knizia’s designs but seem to give other designers more leniency, whether they have their own series or are inspired by the games of others.

His interest in iterations clouds the counting issue, but it stems from wanting people to enjoy games however they like. “For me as a game designer, of course rules are not cast in stone,” he said in a 2002 interview with Funagain, “I would encourage everyone to adapt the game towards what they want to do because every game lives from the people… I’m not making laws, I’m making suggestions for the rules I think work best. But it’s for entertainment. If you have a game and you want to play it differently, then do so. Get the most enjoyment out of it.” Knizia’s games aren’t set in stone, his design philosophy is fluid and his variants and reimplementation provide opportunities for everyone to find the game that works for them.

All that is to say that there is no simple answer when it comes to the number of games Knizia has designed. Whether you feel that it’s less than 450 or more than 800, it’s a lot. The man’s productivity is unparalleled.

In his intelligent and well-reasoned article, Montgomery acknowledges that you could devote an entire thesis to the topic and that the data have certain weaknesses. One of those weaknesses is where the data actually come from. Montgomery used the BoardGameGeek database as a starting point, but Dan Laursen, in a 2020 post, catalogued Knizia designs that aren’t even listed on BoardGameGeek, with many found solely in magazines, books and compendiums.

Which brings us, in a roundabout way, to our choice for ‘U’.

The Ultimate Dice Game Compendium is a collection of 35 dice games, as well as an additional eight variants (you can decide whether that’s 43 games or still 35). Of these, there are six original Knizia designs, with the remainder being classic and traditional dice games. The compendium includes a rule book, dice cup, scoring chips as well as standard and poker six-sided dice. On the back of the box it also claims to contain ‘all the classic favourites’ such as Poker Dice and Drop Dead. Amusingly, included in that list of seven games highlighted on the box are two little known Knizia designs: Tit for Tat and Double Trouble. Classic favourites indeed!

Otherwise it is, in many ways, completely unremarkable. The sort of box you might find in a holiday tat shop when the temperamental British weather means you suddenly need something to do indoors to pass the time. Indeed, one of the few ratings on BoardGameGeek for The Ultimate Dice Game Compendium describes it as a “welcome find on a wet weekend” in Crieff, Scotland.

In the context of our alphabet, however, The Ultimate Dice Game Compendium represents the various books and compendiums that Knizia has written over his career.

Whilst Knizia published several games in magazines from 1985 onwards, it wasn’t until 1990 that his first ‘boxed’ game was published. That same year also saw the publication of his first book: Neue Taktikspiele mit Würfeln und Karte, published in English almost 30 years later. New Tactical Games with Dice and Cards contains the rules of 50 games you can play with cards, dice and a few counters (or 15 games and over 30 variants depending on how you count them). Knizia’s first published game, Complica, makes its second appearance in the book, alongside Tor and Goldrausch (seemingly released in both box and book form in 1990). The collection also includes Dubito, a clear ancestor of the Lost Cities line, and Decathlon (one of five games Knizia would keep for Doomsday, and a variant of which in the book is a precursor to Pickomino).

His next collection was the 1994 compendium Neue Spiele im alten Rom (released in English two years later as New Games in Old Rome). A collection of 14 games themed around the rise of ancient Rome, from city to republic to empire, it’s notable for containing the blueprints of some of Knizia’s later games. Medici started off here as Mercator, King’s Road originated as Imperium, and The Wheel of History became Bunte Runde. The compendium also went on to win the 1994 Essen Golden Feather award, which celebrated the best clarity and presentation of game rules (the trophy was a brass goose quill and inkwell on a chessboard, which Knizia would win again in 2000 for Taj Mahal. We’re not actually sure if the ‘Feather’ is still awarded, the latest winner we’ve been able to find was in 2016 – let us know if you have more information!).

A year later Knizia’s book Kartenspiele im Wilden Westen was published, a book that has been reprinted multiple times over the following decades. Blazing Aces! A Fistful of Family Card Games is a collection of 12-15 (depending on edition) games inspired by Poker, plus over 50 variants. It’s an unusual collection, in that it’s almost narrative in its structure, with fictionalised retellings of Wild West stories surrounding the game rules.

Unfortunately, it’s very much a product of 1995 and includes some racial stereotypes. Sadly, despite minor tweaks and an explanatory paragraph at the beginning, some of the offensive stereotypes are still present in the 2019 edition (read Laursen’s review of the new edition to get more of an idea of the issue, as well as a useful breakdown of all the games included). It’s a shame, since between its covers are East-West (the progenitor of Knizia’s acclaimed Schotten Totten and Battle Line), Oregon (a solo Poker game), Manitu (where the scoring from Tigris & Euphrates and Ingenious originated from), and Stampede (a trading party game about assembling the best Poker hand).

Knizia’s continued interest in Poker has also produced his most recent book, Poker Plain and Simple: A Brief Guide for Beginners, Spectators, and the Curious. Published in 2024, it’s a short guide to the various forms of Poker and includes strategies to “make certain that your opponents’ chips end up on your side of the table!”

These days the name Knizia is associated with tile-laying, auctions and press-your-luck dice and card games. His dice games are many and varied. Pickomino is one of his most successful games ever, selling over a million copies and featuring as our pick (ha!) for the Letter P. We’ve also covered the dice games Age of War and Don’t L.L.A.M.A. Dice in our Knizia alphabet, and there are dozens of others, including Into the Blue, MLEM: Space Agency, High Score and Reif für die Insel (just to name ones we’ve covered here at Meeple Mountain).

Yet in 1999 when he published the book Dice Games Properly Explained, Knizia himself didn’t consider dice as an area of expertise. “It was a very different project,” he said in an interview in 2000 with the Board Game Show, “I have hardly done any games involving dice… so I didn’t have to judge between my own designs and other designs [to include in the book].” He still managed to slide a few of his own designs into the book amongst the almost 150 traditional games included, but it’s interesting to hear Knizia at a time before he mastered dice games.

Two final books/compendiums further highlight Knizia’s interests beyond the modern board games that he’s most well known for. Kartenschach was released in 2000 and is a collection of 16 Chess variants using cards (the title translates as ‘Card Chess’). The cards influence gameplay in a variety of ways, determining which pieces are allowed to move that turn. From this simple premise, Knizia finds ways to include bluffing, push-your-luck, trick-taking, auctions and more. Perhaps Knizia shares our dislike of Chess and was looking for ways to improve it!

His 2004 book Hollywood Lives is something entirely different. Written with Kevin Jacklin (an experienced freeform game player and designer, as well as a Knizia playtester whilst he was based in the UK), it’s a live action freeform party game, bordering on a Live Action Role Playing game (LARP). The players are Hollywood stars who, over the course of 3 or more hours, cast, write and present movie trailers (short plays).

Knizia’s involvement put, what was at the time, a different spin on the genre, introducing money and ‘star power’ to provide indicators of how well individual players have done. “By finding a relatively simple way to incorporate classic board-game mechanisms of negotiation and resource scarcity into the freeform genre,” says David Brain on BoardGameGeek, “Knizia and Jacklin have achieved an impressive compromise that should work for anyone looking to try something a little different with a large group.”

Knizia’s books and compendiums from the 1990s and early 2000s reveal a man overflowing with ideas at a time when the hobby was still reeling from the rise of video games. They act as an outlet for his creativity and curiosity. If every design isn’t a winner, it’s pleasing to see that some have matured beyond their modest beginnings.

When counting Knizia’s games we tend to discount those in collections and books, feeling that those that are worthy are surely the Pinocchios of the batch, those that have ultimately become ‘real games’. Indeed, some people have commented that our celebration of Knizia’s 40 years is 5 years too early, since his games before 1990 were just in magazines. In his analysis, Montgomery removed the games from magazines and books. Bladukas’s Bluesky post suggests that you’d only get close to the claimed 800 by counting all the games in his game books as individual games.

I can understand their sentiments, it feels like there’s a difference between games in a book or magazine and a boxed product of cardboard and counters. Even Knizia himself feels it: “I see publication on two levels,” he said in that Funagain interview, “One is where you have a game published somewhere in printed press and then there are the boxed games. The box games have a higher level/value in my work. If you have a game that’s part of a magazine, people then need to use their own pieces, cut things out, etc. If you have a real box, it’s a real game.”

Those games in books and compendiums and magazines are still games though, they still involve design work to create something new. “I used to have a column in the big games magazine in Germany,” said Knizia to Funagain, “and every issue I would have a new game in there and that would force me to have a new game every two months.” Perhaps his experience of the column is what instilled his rapid design ethos, but regardless of the value you place on games in different formats, those games are still Knizia’s ‘children’.

We should also remember that games found in magazines, books and compendiums were far more popular in the 80s and 90s. They might seem less significant now in this age of the board game resurgence, but people bought and enjoyed those magazines, books and compendiums, they played the games found within them. People still do, they still enjoy games found in books, or else all the recent editions of Knizia’s books wouldn’t have been published. And it’s not just Knizia’s books, Don Eskridge’s recent Hand Games 21 received plenty of critical acclaim (for example, from Dan Thurot of Space Biff). The claim of “more than 800 games published worldwide” at no point says that they all come in a box with components.

Personally, I’ve spent almost 3 years intermittently working on this Knizia Alphabet project, sporadically returning to it to research the man himself and his games. I don’t know the number of designs and I have no real interest in figuring it out. Few would dispute less than 400 games and Knizia’s team claims over 800, resulting in a range of 10-20+ games a year. When Montgomery examined 2024 he reduced the year’s count of 40 design credits down to 17 original designs, which lands squarely in the upper annual range despite his strict approach to removing non-original games.

The interest in the Alphabet has, for me, always been about the productivity and versatility of Knizia as a designer. I am content with the knowledge that Knizia is astonishingly productive and that some of his games are outstanding. The true number isn’t especially important, and changes frequently as new games are announced.

What sticks with me about Knizia is his desire to design games for everyone. That doesn’t mean that a single design will appeal to all, but that he targets different audiences. He aims at a variety of markets, his business background perhaps helping him reach a wider spectrum of players than most hobby designers. The danger of dismissing games because they appeared in books, compendiums or magazines is to forget that those books, compendiums and magazines all had target audiences, audiences who played the games included and may well have found value in them. We ourselves cast the shadow that we throw over the non-boxed games. I called his compendium ‘unremarkable’ earlier in this article, but I’m not really the audience for it. It found a home with a Scotsman in rainy Crieff though, and that is, in its own small way, utterly remarkable.

Uncovering an Undersized Universe in ‘U’

We’re unafraid to unveil that there aren’t umpteen games beginning with ‘U’ in Knizia’s oeuvre (or at least games with English language titles beginning with ‘U’). Here’s the unabbreviated list:

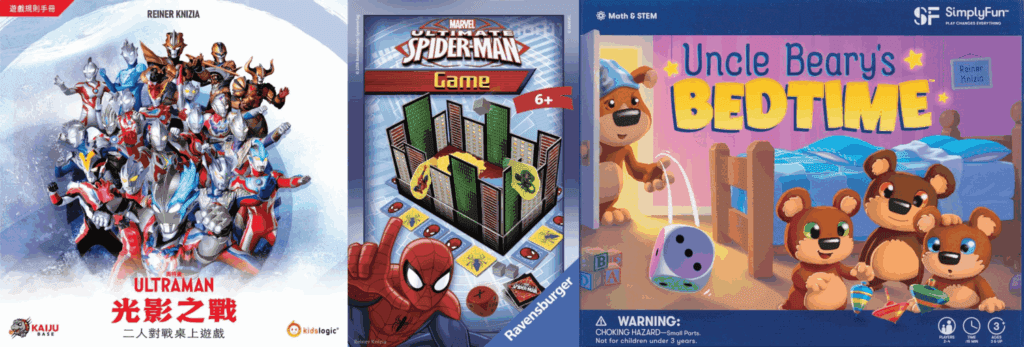

Ultraman: Spirit of Light – We’ve seen the skeleton of 2024’s Ultraman: Spirit of Light before, in both 1993’s En Garde and 2004’s Duell. Both those older games involve sleek and clean card play dictating a simple fencing battle. This latest version changes a fair amount, however, with an ‘Ultra’ mode that involves different Ultraman characters with their own special abilities. There isn’t a huge amount of information (in English) about this release but that core framework is solid and, according to its BoardGameGeek listing, it will bring “immense enjoyment to Ultraman enthusiasts, just like you and me”. What more could you want!

Ultimate Spider-Man Game – Originally published in 2012 as The Amazing Spider-Man Game, the 2014 second edition qualifies this game as a tenuous ‘U’. It’s a dexterity game that sees players dropping cubes into the game box, aiming for coloured areas whilst trying to avoid the holes that represent Lizard’s villainous lair. Succeed and you’ll get to collect Spider-Man tiles, fail and Lizard will pursue Spider-Man around the skyscrapers of the city and you may have to return those tiles you’re trying to collect. It’s simple and aimed at younger audiences, but the use of the box to create the city scape that the hero and villain navigate is a nice touch.

Uncle Beary’s Bedtime – This 2018 game is aimed at Knizia’s youngest audience: ages 3 years and up. It’s a very simple game of rolling dice to move bear cubs from toy cards to bed cards (and sometimes back again), helping to teach pre-schoolers simple numbers and counting. There isn’t a lot more to say about it (reviews are thin on the ground), but those bear cub ‘miniatures’ are super cute and at least their choking hazard warning is age appropriate!

–

And so ‘U’ reaches its ultimate destination. Is it your understanding that our undertaking is an unmitigated utopia of acumen? Have we uplifted you with our unparalleled arguments? Or are we unqualified to use our upper story, our behaviour undisputedly ugly and unacceptable? Unveil your thoughts in the comments below and peruse the rest of the Reiner Knizia Alphabet here!