“The joy of setting your own rules is the breaking of them.”

There are the tales that we tell ourselves, and there are the tales that we tell to other people, and then there are the tales that others tell about us. None of them are true, mind, each a little different and each made different for the telling. But most of them are mostly true, it’s just the lighting that changes.

And the tales that we tell in the tabletop lands are just the same as the tales that we tell elsewhere in life. Tales no taller or shorter or shaggier. Tales touching the truth, and tales in seeing distance of the truth, and tales skirting the truth so precisely that you can map the truth from what isn’t told.

This here’s a tale about a man called Knizia. Or, more truthfully, it’s a tale about the tales told about this Knizia. Two tales, to be precise. Like any tales, they’re related to the truth. I’ll leave it to you to decide whether sibling or cousin or distant-in-law or something so far removed that no law would forbid them marital bliss.

–

Time was, Knizia mined cardboard gold. This would be in the 1990s, right through to what was then the new millennium and, when viewed relatively, still is. Hit after hit after hit after hit. Every year, twice a year even. Reliable genius pouring forth on tap. Ra, Modern Art, Through the Desert, Tigris & Euphrates, Samurai, High Society and more. You’ve likely heard of one or two. Or, perhaps, you haven’t. Might be worth a look if that’s the case, but then again maybe not, every grain of sand’s different and there’s no judgement cast from this side of the page.

Few folk touch the stars, but Knizia did.

But the sand slips through the neck of the hourglass for Knizia as it does for any of us, and the world rotates in its relentless way and things change as they always do. The tap dried up. The hits stopped. The gold turned pyrite. Knizia didn’t go away as such, but for a decade and a half he released kid’s games and movie tie-ins and chuff. Damp squibs that barely glowed before being snuffed out by their own dusty inadequacy.

Some said he abandoned the hobby, turned his back on the very people who had made his name. Some said that he chased the easy money of the mass market, that he sold out in the clichéd way that many successful artists do. And some said that he’d lost his touch or his passion or that the luck had simply run out or that his muse had left him or that he wasn’t all that good in the first place anyway.

And the name Knizia, when it was remembered at all, became synonymous with maths and abstraction, and with endless reimplementations and rethemes, and with eccentricity. Not the good kind of eccentricity, mind, but that unsettling eccentricity some people have that makes one wonder what they do when there’s nobody watching. That special type of eccentricity that causes people to forget that a person is not only in on the joke, but created the joke in the first place.

So followed a dozen years or more of snobbery and mockery by gamers and critics alike, who viewed him as little more than a mathematical alien in a bowtie churning out sub-par kiddie fodder. “It has become increasingly popular to slag off recent Knizia designs as not up to snuff with his earlier classics,” wrote Mike DiLisio back before he was a name, back before he was ‘of the Dice Tower’. “Some people like to opine that the game has passed the good doctor by, and he’s stuck in the past.” Some people indeed did.

And in his absence tabletop games were revived and became more popular than ever before, and Knizia was forgotten by most, a relic from the dark days before the 21st century gaming renaissance, a faded star. New names came to prominence, new ways of thinking, new schools of board game design that didn’t have space for the old guard. “Have games just moved on in recent years, leaving everyone’s favourite bowtie-wearing German irrelevant?” asked and answered Adam Richards, not so very long ago.

Tabletop games flourished and crowdfunding boomed and Knizia was nowhere to be seen, still off courting the family market and doggedly talking about games being for everyone and wearing his bowties.

Until he wasn’t. For, of course, the world turns and wheels spin and fashions change. And Knizia was back from the wilderness, back from his “decade-long doldrums”, back to charm us once more.

His return started with 2017’s The Quest for El Dorado, the bowed head of a penitent man come to beg forgiveness, a humble concession to the trends that had swept him aside, a white flag of surrender, the evidence of pride overcome. To appease the hobby, he took one of the most popular new mechanics that had sprung up in his absence and made it dance to his tune.

That it was magnificent speaks volumes. One of his top 10 designs ever, at least according to the users of BoardGameGeek.

And it was noticed. The Quest for El Dorado “put Reiner Knizia back on the map,” said Jon Purkis, wading through one hundred Knizia’s like estuary mud, “for a lot of people that had got into gaming in the 2010s, there hadn’t been a big successful Reiner Knizia release, and this is the one where people were like ‘oh, who is this guy?’”

Then the Knizian tide came in. Reiner’s ‘Roaring Resurgence’, the ‘Reinerssance’. He was welcomed back, his years in the wilderness absolved, his past successes rediscovered, his new ones respected. More games followed, some new and some spruced up. Babylonia, Yellow & Yangtze, Blue Lagoon, L.L.A.M.A., My City, Mille Fiori, Pollen, Zoo Vadis, and still they come and keep coming. His fans multiplied like bacteria, his fanatics too. “His name is a Shiboleth”, his games are legion. People far smarter than me, and perhaps even smarter than you, had crunched the numbers and analysed the stats and proclaimed that he had indeed gone away and that he was indeed back in a big way.

It’s a tale of rise and fall and rise again, a classic redemption arc, a story of Rebirth. Knizia walks, as we all do, a life of steps and missteps along the road of success, and this was his journey, his tale, the graph charting his progress over his forty years in the business.

–

Of course, in a different light, with a different telling, it’s a tale that comes across a little differently. A different story with a different arc. Just as true, but then again, just as skewed as well.

–

Time was, Knizia mined cardboard gold – this tale starts the same, so you’ll forgive skipping forward a bit. Sand falls, the world rotates and we all will die one day, even Knizia himself.

But in those early years of the new millennium, the turning world didn’t shut the faucet off. The ideas still came. Knizia just diversified, followed his branching path, embraced his mission statement, brought enjoyment to the people. Games are for everyone and everyone has a right to good games, he said way back when the millennium still felt unpunched, even those buying family games based on popular licences.

So followed a dozen years or more of interesting family games and interesting hobby games. Knizia’s portfolio expanded, branching into new markets and introducing ‘good’ games to new audiences. A person can get pretty bored ploughing the same furrow all their life, and there were other challenges to tackle. He didn’t turn his back, he broadened his front, so to speak.

But the slice of people who wanted more art auctions and more power struggles between Mesopotamian states and more Egyptian mythology didn’t rate such casual fodder.

And in the meantime new game designers became names, and new game mechanisms arose and became popular and flourished. Worker placement and deck building and multiplayer solitaire and point salads and knotty tangles of complexity all became the movers and the shakers, intermingling and cross-breeding. Design schools at odds with the simple rules, interaction and depth of Knizia’s turn-of-the-century heyday. We fawned over the new and told ourselves that his time was over. We forgot what Knizia once taught us, that games get us connecting with other people, having fun together. Where Knizia wanted us to look into the eyes of our opponents, we looked down and focused on our own puzzles.

“The Hobby™ at large has prioritized the complicated over the complex, the opulent over the rich,” said Andrew Lynch, an astute Knizian sage if ever there was such a thing. “We want systems on top of systems, hats on top of hats, games that promise variety and “replayability” not through their quality and thoughtfulness, but their breadth… Most games from Reiner Knizia are a rebuke to that ethos. He gives you very little, only what you need, and the rest is in your hands.”

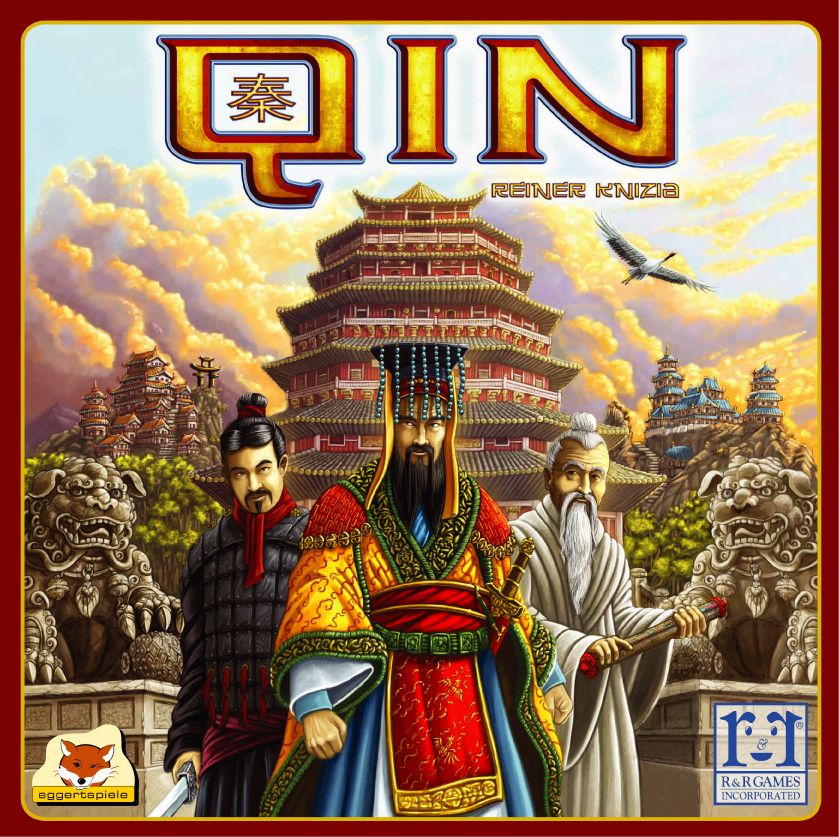

We abandoned Knizia, but he never abandoned us. He kept releasing great games. Our man DiLisio of the Dice Tower referred to them as games that would have been held in much higher esteem had they been released during the “Golden Age of Knizia”. Games like Blue Moon City, Keltis, Municipium, FITS, Whoowasit?, Indigo, Rondo and Orongo. And the poster child for this tale, the best representation of Knizia’s forgotten decade and a half: Qin.

In the middle of his forgotten years, at the very nadir of that dark abandoned moment – 2012’s Qin streamlined and distilled his classic tile-laying and area control experiences into 20-minutes, taking everything Knizia had learned along the way and making it accessible and engaging for a more casual audience whilst keeping things interesting for the gamer.

Voted Knizia’s most underrated game of all time, it is magnificent in its own brief way. One of his top 10 designs ever, at least according to the man himself.

Qin “effortlessly showcases the Good Doctor’s ability to generate hard stares over a handful of non-matching colors,” said Dan Thurot recently, discussing both Qin and its updated version Gazebo, “it’s Knizia at his best, not only as a creator of mechanisms, but as an abstractionist”.

And it was not noticed. Because the trouble with making games for everybody is that many of those games aren’t for everybody. Qin, for all its blistering speed and vivacity or perhaps because of them, was passed over and ignored and quickly forgotten, its embers extinguished before people noticed the glow. Who knows, maybe Gazebo will help more to see the light this time. Or maybe not. We are all grains of sand in the world’s hourglass after all and, as has been said before, every grain is different.

Knizia’s retreat and return as evidenced was, in fact, nothing of the sort. A false positive, a facade. The data created a tempting illusion and we embraced its narrative neatness, eager to ignore our own fickle nature and our shortsighted memory. But the data was always biased by a hobby that had turned its back on him, that had forgotten him, that had been entranced with new shiny baubles. The Reinerssance was not real and no Resurgence Roared because there was never anything to surge back from. The tide may go out and come back in but the ocean is always there.

We came back to him and were welcomed, our betrayal absolved as we rediscovered his past successes and embraced his new ones. And when we returned to him, he was as he always had been. Genial and inventive and endlessly enthusiastic about games and wearing his bowties. More games followed, some new and some spruced up. Babylonia, Yellow & Yangtze, Blue Lagoon, L.L.A.M.A., My City, Mille Fiori, Pollen, Zoo Vadis, and still they come and keep coming. The games and the fans and the fanatics multiplied, and all proclaimed that the age of Knizia had returned to us, when, in fact, it was the other way around.

It’s a tale of straying from the path and finding it again, a classic redemption arc, a story of Rebirth. We all walk a life of steps and missteps along the road. Sometimes it just takes us a while to find the path again and resume our journey.

–

And so ends the second tale, no less true than the first and no less meaningful for it. Two stories and two truths, two games and two ‘Q’s. The triumphant come back and the refute that there was anything to come back from.

And the actual truth? Perhaps one of the tales is the truth. Perhaps neither are. Or perhaps the truth threads its way through both of them like veins of mold through stilton or cambozola.

Whether he turned his back or was turned upon, there is no doubting the sea change in the 2020s. And of course there are tales told about the reasons for this too.

Some say that the hobby had grown large enough for his mercantile nature to find it profitable again. Some say that changing fashions have brought Knizia’s design ethos back to prominence. Some say that it’s the result of Brexit, that great kick in the teeth to collaboration, causing Knizia to move back to Germany and reconnect with former playtesters. Some say that it’s down to the Z-Man Euro Classics line in the mid-2010s, financially unsuccessful reprints that prompted critics to eat their words and Knizia to reflect and revisit. Some say it was the pandemic which gave him time to focus on design and creativity.

Some say other things too. The backlash is never far away for those in the spotlight, and there are those who are ever ready to push the walker off the path. The repeated cries of ‘retheme’, ‘cash grabs’ or ‘maths’, as if ‘maths’ is a bad thing, as if ‘balance’ – that thing so many gamers demand in a game – isn’t simply maths dressed up. Voiced doubts over originality and the number of ‘true’ designs he has. Questions about how much of a role Knizia actually plays in the design process. Assumptions that the Knizia fan will uncritically lap up anything he releases, as if Knizia fans aren’t the most particular of all.

These stories and more flutter in forums and on social media, as asides in articles and videos, statements and echoes that ring in our collective consciousness until they coalesce into narratives that help us make sense of the world, even if the narratives themselves don’t make sense.

These are the tales that we tell ourselves, and these are the tales that we tell each other and, for Knizia, these are the tales that others tell about him. He doesn’t seem to mind, of course. What matters are the games and how they bring joy to the people who play them. These are the things that have always mattered to him and, looks to be, always will.

Maybe that’s for the best.

–

The Reiner Knizia Alphabet resumes as normal next time.

Andrew — this is, by far, the best in the series so far. And given the quality of those previous entries, you set a bar I thought was impossibly high and catapulted over it.

Well done.

Thank you, that’s very kind of you to say 🙂 It’s a fun series to write and this one was particularly enjoyable.