At its core, Sidereal Confluence: Trading and Negotiation in the Elysian Quadrant (yes, that is actually the title) is a resource conversion, cube pushing euro which relies on you to maximize an engine. The gameplay is solely built around a simple resource conversion system. Take this example – if I have the card below, I can convert three blue cubes into two space ships, two grey, one brown, and one green cube.

What makes Sidereal Confluence unique is emblazoned in the title of the game – trading and negotiation. Though it may seem like the gameplay is about maximizing your engine, the real core of the game is about how well you can negotiate with your opponents.

Gameplay Overview

In Sidereal Confluence, you and 3-8 friends are all different alien species coming together to develop technology to better all of your races. In each round of the game, your goal is to collect the resources you need to develop new technologies. Whenever you develop one of these technologies, you score points for sharing it with the other players. Each round is divided into three phases – Negotiation, Execution, and Confluence.

Negotiation

The core gameplay centers around the negotiation phase of each round. Players can negotiate for resources, victory points, converters (like the one shown at the beginning), future resources, and whatever other deals players can come up with.

During this phase, players are seeking to collect resources they can use in their converters, and developing technologies. If a player collects the resources needed for a technology, they can immediately develop it, but only during the negotiation phase.

Execution

The Execution phase is simple: run any converters you have. Each converter can only be run once, and they are run simultaneously so you need all of the resources at the beginning of the execution phase.

Confluence

Each round ends with the confluence phase, during which any technologies developed are given to all other players in the game. After that, players score points for the technologies they personally developed. Finally, players bid on new technology contracts for future rounds.

Asymmetry

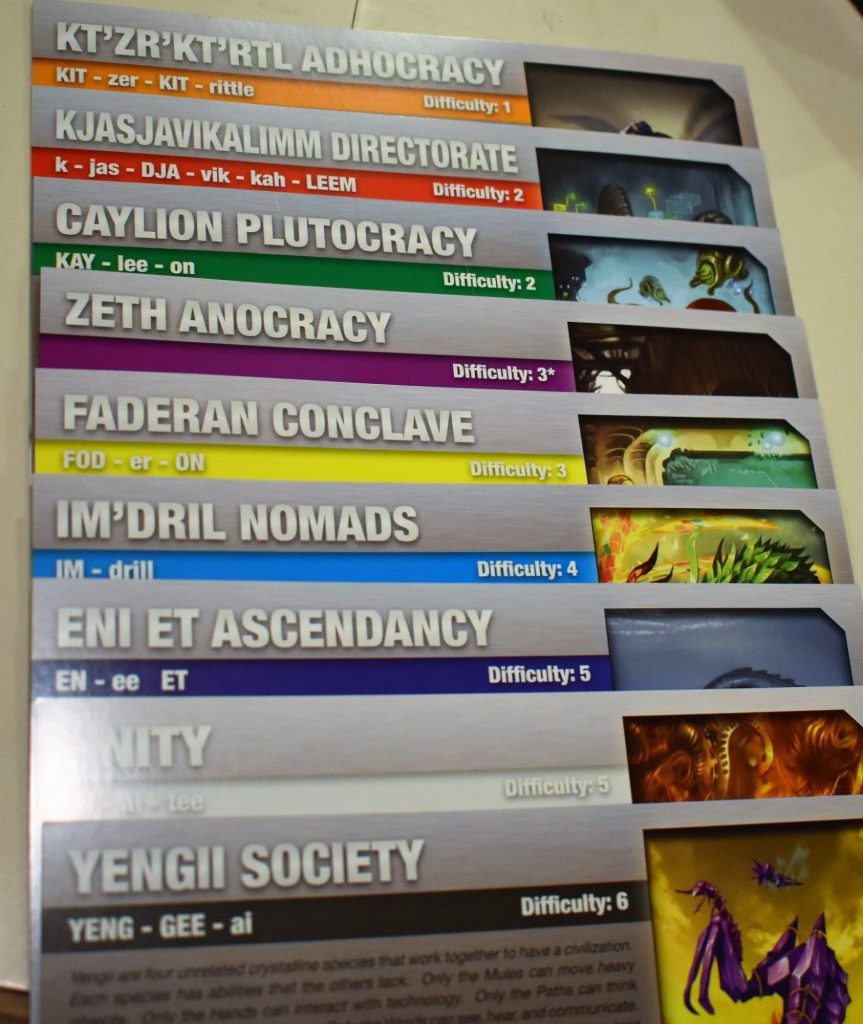

One of the most important aspects of Sidereal Confluence is the asymmetric player powers. Since each player is a unique alien race, each is given a series of dramatically different player powers that drive their strategy.

Playing as two different races feels like two uniquely different games. Take the Eni et Ascendancy, for instance. They have a series of converters that will quickly grow the number of resources the owner has. The trick is, they can’t use those converters and so they need to be traded away.

On the other hand, the Zeth add an additional phase to the game where they can steal resources from any player who hasn’t traded with them that round. As a result, players are forced to make bad trades with the Zeth just to avoid having them stolen later in the round.

The designers did two additional things to make the asymmetric powers work well. First, they identified a difficulty level for each race. This allows for players with a variety of familiarity with the game to play together in a more balanced setting. Second, they provide each race with some advice for how to best play their powers. This further levels the playing field by giving each player an idea of the direction to take their race and can help match players with races that may better suit their play style.

Final Thoughts

I’ve always found it interesting that one of the most common gateway games, Settlers of Catan, has a strong negotiation component to the gameplay, but negotiation isn’t present to the same extent in many other games. Games like Rising Sun, John Company, and Twilight Imperium encourage deal-making to establish alliances or status. The negotiation in these games is centered around a quid pro quo; some mutually beneficial deal that elevates both players.

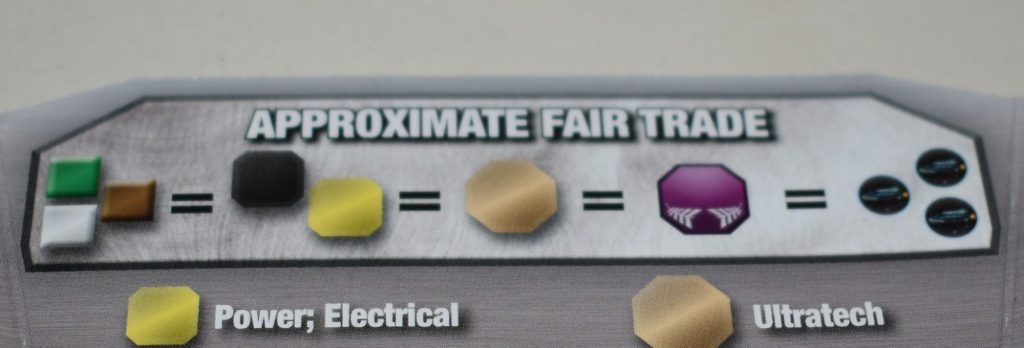

The negotiation in Sidereal Confluence is much closer to the “trade four sheep for three wood” version of negotiation in Catan. It isn’t surprising that this type of negotiation is not present in many resource conversion/engine building euro style games because of how challenging it is to determine the value of resources. The designers of Sidereal Confluence took a brilliant step in alleviating this burden by including approximate trading values on the player aid. This simple gesture eliminates any uncertainty about the value of resources.

Sidereal Confluence is one of my favorite games released in the last few years. The gameplay is so simple, yet deep and interesting. So many modern board games are designed to pit opponents against each other in a battle of wits. Sidereal Confluence does this in a purer way than nearly any other game I’ve seen – by forcing players to use their skills in communication to out play each other. The negotiation feels more primal and instinctual than a drawn out series of well-planned actions in a game like The Great Zimbabwe or Great Western Trail.

There is one big challenge with Sidereal Confluence and that is gathering the right players. Since the game relies on negotiation and the interaction of the players around the table, the success or failure of the game is more group dependent than most other games. If all of the players don’t understand the system or are not interested in the game, it can throw off everything. Also, since the game plays 4-9 players, it isn’t the easiest game to get to the table.

It took me a while to finally get to play Sidereal Confluence, but I am sure glad I did. I’ve explored nearly half of the alien races, and I’m excited to explore the others. The ones I have played so far have each resulted in a very different game. It’s rare for a game to let you embrace creativity in the ways Sidereal Confluence does and that creativity is what is most captivating about the game to me. If there’s a deal that can be made, I’m going to figure out how to make it.

Due to the combination of length, unique mechanisms, and asymmetry Sidereal Confluence won’t be for every game group. That being said, if you have a group that likes heavier resource management and engine building games but would also be interested in negotiation I hope you take a look at this game. It is weird and holds a really unique spot in my collection but that’s also exactly why I think it is a great game.

Have you played New Angeles yet? I am curious as to how the negotiation portion compares to this. I have heard this can be a beast at larger play counts, but also quite the experience. What was the highest player count you managed here?

There is a fairly major rules error in this review:

In the “Execution” section here, you say “Each converter can only be run once, but they can be run in any sequence so you don’t need all of the resources at the beginning of the execution phase.”

While in the rulebook: “Economic converters are run simultaneously. As such, the output of one converter cannot be used as the input for another.” (Under Economy Phase on page 6)

This is important as trading for the resources you need is the core of the game. Having to run the converters simultaneously means you have to get everything you would want to use during the trade phase.

Thanks for pointing that out. I’ll correct that.

-trade victory points

You can never trade victory points, its the one thing in the game that is kept secret and never touched

– 3 to 8 players

The game plays up to 9, and recomends beginners start with at least 4 players as 3 player games can be excessively cut throat.

Good review, just a couple minor things that may throw some new players off when they open the box.

If you read carefully the author refers to you and 3-8 friends so it is correct even if easily mistaken. Also Tauceti deichman says that the game can be played in 3 players but it is more ruthless

Small correction: The second paragraph under “Asymmetry” is about the Eni et, but later in the paragraph calls them Unity.

Thanks Colin, I tweaked the verbiage.