Disclosure: Meeple Mountain received a free copy of this product in exchange for an honest, unbiased review. This review is not intended to be an endorsement.

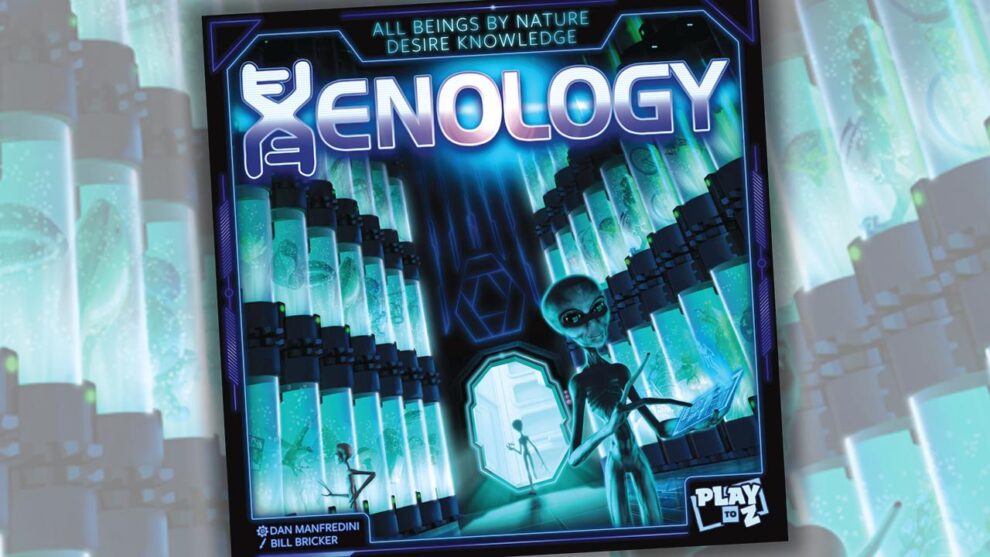

When I saw Xenology, I was immediately piqued because it reminded me of a friend’s prototype, a game about studying humanity from the perspective of an alien race. I wanted to see the track a different design mind might do with a similar idea—one of my favorite pastimes.

Unfortunately, Xenology doesn’t capture the weirdness of my friend’s game, nor does it capture the magic of the foundational eurogame elements it deploys across its own design. It’s a “do A so you can acquire C so you can do B and score some points” sort of game, nothing more, nothing less. It has the trappings of a much more interesting game, that resolves into something whose end result feels arbitrary and mushy, and ultimately just fades in with a broad swathe of other games in spite of the unique setting.

Alien bureaucrats demand RFPs

In the game, you’re an alien trying to advance in the alien hierarchy by studying human beings. The process by which you do this is reasonably straightforward.

In the center of the board there’s an action cross of sorts, at the intersection a center action (Mission Control) with four actions that are arranged around it in an offset cross. You start with three alien meeples (cute) in the mission control area and three aliens in cold storage, which is a reserve. On your turn, you move one of your aliens to an adjacent area in the action cross and perform the action. There are also separate flying saucer tiles that you can send a single meeple to as an action.

The locations are various timing puzzles. In one, you place contracts in the form of cards with icons on your player board, moving up 5 different color tracks that correspond to the color of the card. You have limits on how many contracts you can have active at once. In another location, you claim and collect chits that will combine with your completed cards at the end of the game to form a scoring multiplier.

The third location launches the flying saucer tiles, which send meeples from the flying saucer tiles down to a hex map of Earth., There, you playa mini-game where you try to move the meeples to the correct symbol locations on your contracts.

Mission control has players either exploring the planet (flipping tiles) or pulling their aliens back from the hex map. When aliens leave Earth, they leave behind negative points on the board and cover matching icons on their contracts. Those covered contracts are then used at the final action location, moving the cubes from the cards to a grid that vaguely resembles a DNA sequence. Each cube on the grid is two points at the end of the game.

If your eyes glaze over with that description, it’s because no part of it is particularly exciting. The process is essentially:

- grab contracts

- place your aliens in a pattern on a hex map

- pull them back

- go to a location where you move cubes from your contracts for points.

Cube economy woes

I was hoping for Xenology to evoke one of my favorite games, Hansa Teutonica, which has one of the most razor-sharp resource economies in any eurogame. In both of these games, you’re managing an ever-dwindling supply of wooden cubes that are the primary way you interact with the game. In Hansa Teutonica, this inventory is how you claim points on the board and interact with other players; in Xenology, they’re a nuisance. You need cubes to do everything in the game, and in order to win, you need to have enough cube-flow to keep pace with the cubes that you’re assigning to point generation as the game develops. Also, they’re the endgame trigger, which means that the game feels like you’re on this alien bureaucratic treadmill where it’s more important to keep filing reports and reporting into your alien boss than it is to do anything X-Files related.

It all left me with the feeling of having played a smooth game, one with no contours, no sharp edges, and no particularly meaningful big plays or decisions. Even the player powers are underwhelming, as most of them just give you opportunities to make a given point scoring combo a little longer.

For a game with such a compelling idea and all the bones of a highly interactive and competitive game, it manages to be a solo, isolated affair, where you’re always finding yourself near-missing interaction with the other players, rather than ever getting in their face and competing over anything.

I wish I had more to say about the game, because the concept is compelling. Ultimately, come for the cute meeples, but don’t stay in space; there are other far more interesting games back here on terra firma.