Hello and welcome to ‘Focused on Feld’. In this series of reviews, I am working my way through Stefan Feld’s entire catalogue. Over the years, I have hunted down and collected every title he has ever put out. Needless to say, I’m a fan of his work. I’m such a fan, in fact, that when I noticed there were no active Stefan Feld fan groups on Facebook, I created one of my own.

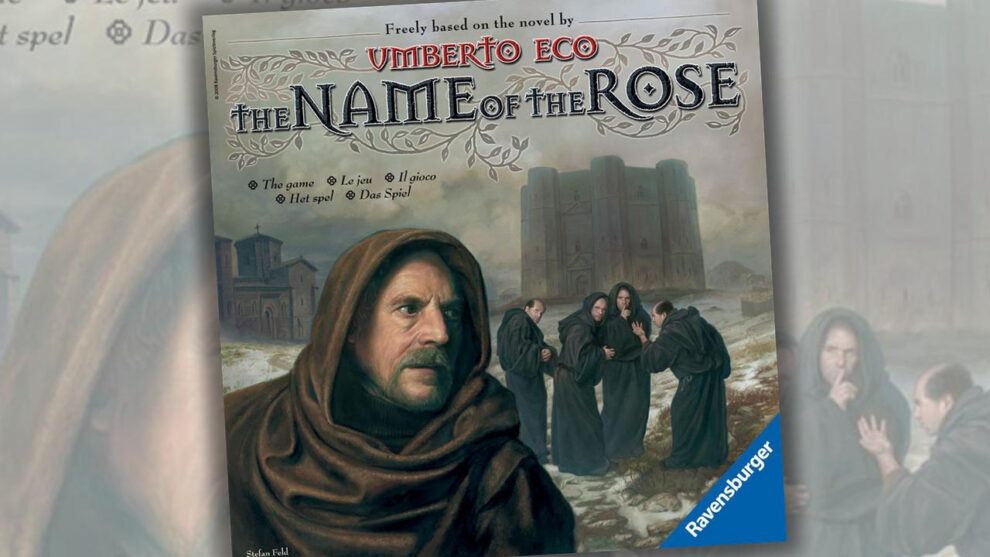

Today we’re going to talk about 2008’s The Name of the Rose, his 5th game. This marks the first time that Feld would ever publish a standard, Ticket to Ride sized game (a feat which wouldn’t be repeated until 2016’s Jórvik). Inspired by Umberto Eco’s 1980 novel by the same name (and most likely the movie adaptation from 1986), it’s also the first of only two games designed by him that are based on a previously existing IP (the other being 2000’s Pillars of the Earth: Builders Duel).

Taking place in 14th century Italy, The Name of the Rose drops the players squarely into the middle of the story. William of Baskerville and his assistant Adso are in full on investigation mode, and the players take on the roles of the monks living within the abbey as they work to avoid scrutiny… scrutiny which, unabated, may see them burning at the stake. A hidden identity game unlike any you’ve ever played, The Name of the Rose is a clever game of cat and mouse that has the players casting aspersions not only on the other players, but themselves as well.

Overview

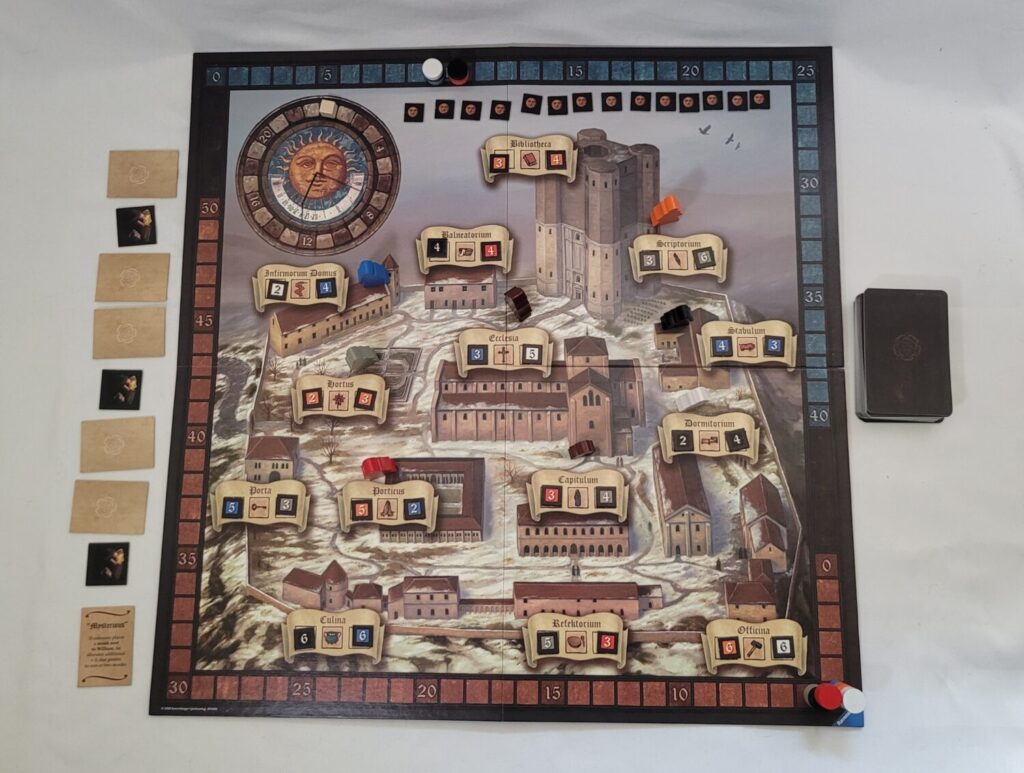

The game board for the game features several locations within the abbey, each populated with two colored Work tiles. At the start of the game, several of these locations will have a random monk figurine assigned to them—red, blue, orange, black, white, and grey—or the William or Adso figurines. At the start of the game, each player receives several action cards as well as an identity card that shows which monk they will be representing over the course of the game. This identity is kept hidden from other players.

The game is played over a series of seven rounds (called days). Before each new round begins, an Event tile is revealed which will adjust the game rules for the upcoming round. Over the course of each round, players will play cards from their hands to move monks around within the abbey, gaining or earning suspicion points depending on where they go. If they’re sent to a location that contains a Work tile matching their color, they lose suspicion equal to the number printed on the tile, and the player collects the tile. However, if they’re sent to a location that does not contain their color, then they gain suspicion equal to the total of the numbers printed on the tiles at the location.

Each action performed removes time from the day clock. Collected Work tiles can be returned to the supply to remove less time. Once the clock runs out, the day comes to an end and the suspicion gained is converted into movement along the Clue track. If you’ve moved the least along this track at the end of the game, you win.

William, Adso, and the Passage of Time

William and Adso are not like other monks. When a William/Adso card is played, the player has two options: move the William figurine to a new location, using five hours of the game clock in the process OR move Adso to a new location without burning up any time. Once moved to a new location:

– William is used to adjust the position of every monk at that location +/-3 on the Clue track.

– Adso is used to adjust the position of every monk at that location +/-5 on the Suspicion track.

While Adso’s ability may not be as powerful as William’s, the ability to have an effect on the Suspicion track without moving the needle on the game clock is huge. This is because whoever causes the day clock to run out will collect the current Event tile, and that will cause them to move an extra two spaces up the Clue track at the end of the game per Event tile they’ve collected.

This aspect of the game can quickly become very frustrating. Aside from your monk being in a position to earn very few, if any, clue points should the round end, there is very little incentive to end it. Nobody wants to run out the clock, so the end of every round almost always devolves into all the players doing everything they can to avoid being the one to do so. Eventually, once someone finds themselves holding nothing but high value cards and having no Work tiles at their disposal, they’ll be forced to end the current round whether they want to or not.

The amount of time it takes for this inevitable conclusion is entirely dependent on the luck of the draw. Sometimes it mercifully ends quickly. But, in my experience, it almost always causes things to drag on far more than is tolerable. So much so, in fact, that I never play the full seven day cycle anymore. Instead, I use a variant in which only four standard days are played. Normally, the sequence would be to play a day, perform a ‘reveal’ (a round in which each person reveals one color that they are not), then another two days followed by another reveal, another two days followed by another reveal, and a sixth day. Then, there is a seventh non-standard day in which players try to guess what color they think the other players are, and the players gain movement on the Clue track if their color was guessed.

This four day variant eliminates one of the two days in between the first and third reveal. Playing with this variant, the players still get the feeling of having played the full seven day cycle without having to suffer through the entire seven days’ worth. It shaves off a good 30-40 minutes worth of time. I’m normally not one to do a lot of house ruling, but I make an exception in this case.

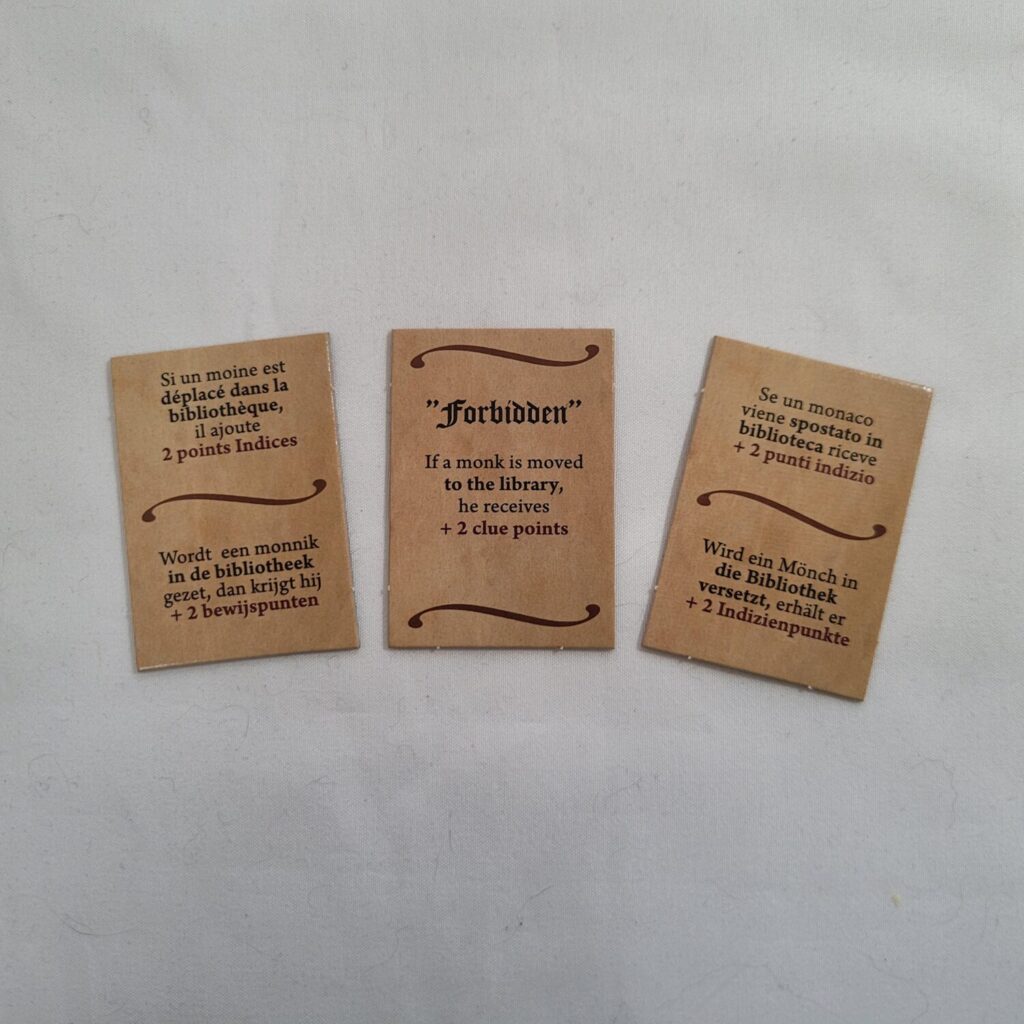

And, whilst I’m on the rampage about things that I find bothersome about this game, let’s talk about the Event tiles and how they relate to the game board. In this game, Ravensberger has tried to be very smart by including a single, large rulebook that contains the rules in multiple languages and a set of Event tiles for each of those languages as well. I have no issue with this. What I do take issue with is that these Event tiles repeatedly refer to one of the locations on the game board, but don’t actually use the name of the location.

Take for example the “Forbidden” Event tile. In English, this tile reads “If a monk is moved to the library, he receives +2 clue points”. But, there is no “library” on the game board. There’s a “Bibliotheca”. If I hadn’t taken a few years of French in high school, I might not know which building the Event tile was referring to. The tiles that reference this location in other languages are generally close, and a reasonably smart person might be able to infer which location is being referred to—biblioteca (Italian), die Bibliothek (German), bibliotheque (French), de bibliotheek (Dutch)—but none of them simply refer to the location as it is printed on the board. Another example is the “Incredulous” Event tile which refers to “the church”. There is no “church” printed on the game board, but there are several locations which seem vaguely church-like such as “Scriptorium” (which sounds like the word scripture), “Porticus” (which features an icon of praying hands), or “Ecclesia” (with an icon of a cross). With a rudimentary understanding of Latin, I am able to infer that “Ecclesia” is most likely the right answer, but I can’t be sure. My initial thought was to look at the Event tiles for the other languages to see if they paired up, but they’re even worse than the English translation—chiesa (Italian), die Kirche (German), l’eglise (French), de kerk (Dutch). Instead of the word “church”, wouldn’t it have just been better to use the word “Ecclesia” instead since that’s what’s actually printed on the board? What’s even more frustrating is that each location on the board has a unique icon associated with it, so why not just use the icon? It boggles the mind.

I’m all for immersion, but I shouldn’t have to actually roleplay William of Baskerville just to play this game.

Thoughts

I was lucky enough to stumble across a ‘still in shrink’ copy of The Name of the Rose shortly after I embarked on this journey to review every game Stefan Feld has ever designed, but until recently, I’d never had the opportunity to get it played. A couple of months ago, I’d finally reached the point where it was time to break it out and get it played. I was very excited. But that excitement didn’t last.

To say that my initial excitement has waned would be an understatement. When it comes to this game, my excitement to play it again is almost non-existent. It’s not because it’s a bad game, because it isn’t. It’s well-conceived, brilliantly designed, and beautifully executed. The Name of the Rose hits all the right notes when it comes to intrigue. Trying to maneuver yourself into the winner’s seat without being too conspicuous presents an interesting challenge.

The problem isn’t the gameplay. The problem is that the game, as a whole, just isn’t very compelling. Once you’ve played through it a few times, there’s nothing left to discover. Remember that time you watched your favorite movie for the first time? Remember the sense of wonder as you watched the story unfold? Remember that sensation you felt when the twist was revealed or the music score hit in just the right way or that actor gave a life changing performance?

Remember how you walked out of that theater determined to share that elation with other people? Remember how you talked it up and finally convinced them to watch it with you? And, remember how it just didn’t hit the same way it did that first time as you watched it over and over again? Maybe you noticed a few things you missed the first time around. Maybe, knowing the story already, you were able to pay more attention to the cinematography or the score. The enjoyment was still there, but it wasn’t as palpable or as powerful as it was that first time around. And, remember how the only real pleasure you gain from it anymore is just watching other people enjoy it for that very first time?

That’s how The Name of the Rose is for me now. I’ve milked it for all its worth. I’ve squeezed every drop of joy and wonder the game has to offer out of it, and all that I’m left with now is the pleasure of sharing the experience with others. It’s an experience I am pleased to share, and it’s one that I think is valuable. But, it’s just not one I’m keen to seek out.

I’m glad to have this game in my collection, but given the rest of Feld’s catalogue to choose from, it’s doubtful The Name of the Rose is going to be the one that I choose to play, especially when I have options like The Castles of Burgundy or Civolution at hand. I imagine that The Name of the Rose was something pretty special when it was initially released. But, by today’s standards, it’s just a sapling struggling for relevance in a forest full of giant trees.